Learning by Writing

The Assignment: Proposing a Solution

In this essay you’ll first carefully analyze and explain a specific social, economic, political, civic, or environmental problem—a problem you care about and strongly wish to see resolved. The problem may be large or small, but it shouldn’t be trivial. It may affect the whole country or mainly people from your city, campus, or classroom. Show your readers that this problem really exists and that it matters to you and to them. After setting it forth, you also may want to explain why it exists. Write for an audience who, once aware of the problem, may be expected to help do something about it.

The second thing you are to accomplish in the essay is to propose one or more ways to solve the problem or at least alleviate it. In making a proposal, you urge action by using words like should, ought, and must: “This city ought to have a Bureau of Missing Persons”; “Small private aircraft should be banned from flying close to a major commercial airport.” Lay out the reasons why your proposal deserves to be implemented; supply evidence that your solution is reasonable and can work. Remember that your purpose is to convince readers that something should be done about the problem.

184

These students cogently argued for action in their papers:

Based on research studies and statistics, one student argued that using standardized test scores from the SAT or the ACT as criteria for college admissions is a problem because it favors aggressive students from affluent families. His proposal was to abolish this use of the scores.

Another argued that speeders racing past an elementary school might be slowed by a combination of more warning signs, surveillance equipment, police patrols, and fines.

A third argued that cities should consider constructing public buildings with “living walls” in order to reduce energy consumption, improve air quality, and allow for urban agriculture.

Facing the Challenge Proposing a Solution

The major challenge writers face when writing a proposal is to develop a detailed and convincing solution. Finding solutions is much harder than finding problems. Convincing readers that you have found a reasonable, workable solution is harder still. For example, suppose you propose the combination of rigorous exercise and a diet low in refined carbohydrates and sugar as a solution for obesity. While these solutions seem reasonable and workable to you, readers who have lost weight and then gained it back might point out that their main problem is not losing weight but maintaining weight loss over time. To account for their concerns and enhance your credibility, you might revise your solution to focus on realistic long-term goals and strategies. For instance, you might recommend that friends walk together two or three times a week to get more exercise. You might also list sources of recipes for easy, tasty, and filling meals that are low in refined carbohydrates.

185

To develop a realistic solution that fully addresses a problem and satisfies the concerns of readers, consider questions such as these:

How might the problem affect different groups of people?

What range of concerns are your readers likely to have?

What realistic solution addresses the concerns of readers about all aspects of the problem?

Generating Ideas

Identify a Problem. Brainstorm by writing down all the topics that come to mind. Observe events around you to identify irritating campus or community problems you would like to solve. Watch for ideas in the news. Browse through issue-oriented Web sites. Look for sites sponsored by large nonprofit foundations that accept grant proposals and fund innovative solutions to societal issues. Be sure to stick to problems that you want to solve, and star the ideas that seem to have the most potential.

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

Can you recall any problem that needs a solution? What problems do you meet every day or occasionally? What problems concern people near you?

What conditions in need of improvement have you observed on television, on the Web, or in your daily activities? What action is called for?

What problems have been discussed recently on campus or in class?

What problems are discussed in blogs, online or print newspapers, or newsmagazines such as Time, the Week, or U.S. News & World Report?

Consider Your Audience. Readers need to believe that your problem is real and your solution is feasible. If you are addressing classmates, maybe they haven’t thought about the problem before. Look for ways to make it personal for them, to show that it affects them and deserves their attention.

Who are your readers? How would you describe them?

Why should your readers care about this problem? Does it affect their health, welfare, conscience, or pocketbook?

Have they ever expressed any interest in the problem? If so, what has triggered their interest?

Do they belong to any organization or segment of society that makes them especially susceptible to—or uninterested in—this problem?

What attitudes about the problem do you share with your readers? Which of their assumptions or values differ from yours, and how might this difference affect how they view your proposal?

186

Learning by Doing Describing Your Audience

Learning by Doing Describing Your Audience

Describing Your Audience

Write a paragraph or so describing the audience you intend to address. Who are they? Which of their circumstances, interests, traits, social circles, attitudes, and values best prepare them to grasp the problem? Which make them most (or least) receptive to your solution? If aspects of the problem or the solution especially appeal (or do not appeal) to them, consider how to present your ideas most persuasively. If you want a second opinion, share your analysis with a classmate.

Think about Solutions. Once you’ve chosen a problem, brainstorm—alone or with classmates—for possible solutions, or use your imagination. Some problems, such as reducing international tensions, present no easy solutions. Still, give some strategic thought to any problem that seriously concerns you, even if it has stumped experts. Sometimes a solution reveals itself to a novice thinker, and even a partial solution is worth offering.

For more on using evidence to support an argument, see Learning by Writing in Ch. 9.

Consider Sources of Support. To show that the problem really exists, you’ll need evidence and examples. If further library research will help you justify the problem, now is the time to do it. Consider whether local history archives, newspaper stories, accounts of public meetings, interviews, or relevant Web sites might identify concerns of readers, practical limits of solutions, or previous efforts that will help you develop your solution.

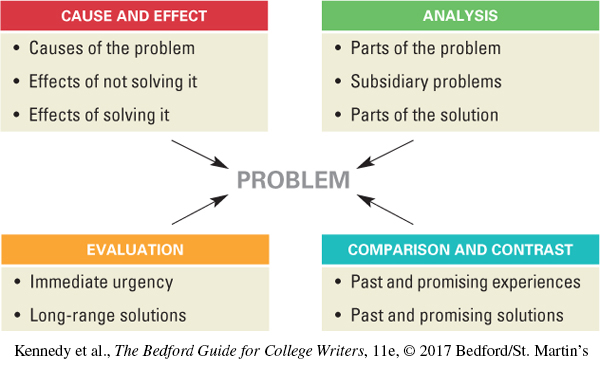

For more on causes and effects, see Ch. 8 and Identifying Causes and Effects in Ch. 22. For more on analysis, see Analyzing a Subject in Ch. 22.

For more on comparison and contrast, see Ch. 7. For more on evaluation, see Ch. 11.

187

Planning, Drafting, and Developing

For advice on finding a few sources, see sections A and B in the Quick Research Guide.

Start with Your Proposal and Your Thesis. A basic approach is to state your proposal in a sentence that can act as your thesis. This is the strategy that Lacey Taylor used for her thesis.

| TAYLOR’S THESIS | The campus community should use methods such as posting warning signs, starting an awareness program, and investing in new technology like cameras, chain alarms, and tracking devices to help solve this problem. |

For more on stating a thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20.

Let’s look at another example, showing a first draft of a thesis and the proposal it was based on.

| PROPOSAL | Let people get divorced without having to go to court. |

| WORKING THESIS | The legislature should pass a law allowing couples to divorce without the problem of going to court. |

From such a statement, the rest of the argument may start to unfold, often falling naturally into a simple two-part shape:

For more on outlines, see Organizing Your Ideas in Ch. 20.

A claim that a problem exists. This part explains the problem and supplies evidence of its significance—for example, the costs, adversarial process, and stress of divorce court for a couple and their family.

A claim that something ought to be done about it. This part proposes a solution to the problem—for example, legislative action to authorize other options such as mediation.

These two parts can grow naturally into an informal outline.

Introduction

Overview of the situation

Working thesis stating your proposal

Problem

Explanation of its nature

Evidence of its significance

Solution

Explanation of its nature

Evidence of its effectiveness and practicality

Conclusion

188

You can then expand your outline and make your proposal more persuasive by including some or all of the following elements:

Knowledge or experience that qualifies you to propose a solution (your experience as a player or a coach, for example, that establishes your credibility as an authority on Little League or soccer clubs)

Values, beliefs, or assumptions that have caused you to feel strongly about the need for action

An estimate of the resources—money, people, skills, material—and the time required to implement the solution (perhaps including what is available now and what needs to be obtained)

Step-by-step actions needed to achieve your solution

Controls or quality checks to monitor implementation

Possible obstacles or difficulties that may need to be overcome

Reasons your solution is better than others proposed or tried already

Any other evidence that shows that your suggestion is practical, reasonable in cost, and likely to be effective

Learning by Doing Reflecting on a Problem

Learning by Doing Reflecting on a Problem

Reflecting on a Problem

Reflect on a problem about which you feel strongly, such as parking availability at school, high tuition, or bad drivers. How could you rectify the problem? Make a brief outline of an essay proposing your solution.

Imagine Possible Objections of Your Audience. You can increase the likelihood that readers will accept your proposal in two ways. First, start your proposal by showing that a problem exists. Then, when you turn to your claim that something should be done, begin with a simple and inviting suggestion. For example, a claim that national parks need better care might suggest that readers head for a park and personally size up the situation. Besides drawing readers into the problem and the solution, you may think of objections they might raise—reservations about the high cost, complexity, or workability of your plan, for instance. Persuade readers by anticipating and laying to rest their likely objections.

189

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Interested Parties

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Interested Parties

Reflecting on Interested Parties

Sketch a picture or diagram that visualizes the problem for which you are offering a solution. Looking at your sketch, determine who might have an interest in either the problem itself or your proposed solution. Could there be individuals who have an interest in a different solution? How much of an interest would each party have in your solution? What objections might each party have to your solution?

For more pointers on integrating and documenting sources, see Ch. 12, as well as sections D and E in the Quick Research Guide.

Cite Sources Carefully. When you collect ideas and evidence from outside sources, you need to document your evidence—that is, tell where you found everything. Follow the documentation method your instructor wants you to use. You may also want to identify sources as you introduce them to assure a reader that they are authoritative.

According to Newsweek correspondent Josie Fair, . . .

In his biography FDR: The New Deal Years, Davis reports . . .

While working as a Senate page in the summer of 2015, I observed . . .

For more about integrating visuals, see section B in the Quick Format Guide.

Introduce visual evidence (table, graph, drawing, map, photo), too.

As the 2010 census figures in Table 1 indicate, . . .

The photograph showing the run-down condition of the dog park (see Fig. 2) . . .

Revising and Editing

For more revising and editing strategies, see Ch. 23.

As you revise, concentrate on a clear explanation of the problem and solid supporting evidence for the solution. Make your essay coherent and its parts clear to help achieve your purpose of convincing your readers.

Clarify Your Thesis. Your readers are likely to rely on your thesis to identify the problem and possibly to preview your solution. Look again at your thesis from a reader’s point of view.

| WORKING THESIS | The legislature should pass a law allowing couples to divorce without the problem of going to court. |

| REVISED THESIS | Because divorce court can be expensive, adversarial, and stressful, passing a law that allows couples to divorce without a trip to court would encourage simpler, more harmonious ways to end a marriage. |

190

THESIS CHECKLIST

Does your thesis clearly identify the problem?

Does it suggest a solution?

Could thesis be refined or made more specific based on evidence or insights that you gathered while planning, drafting, or developing your essay?

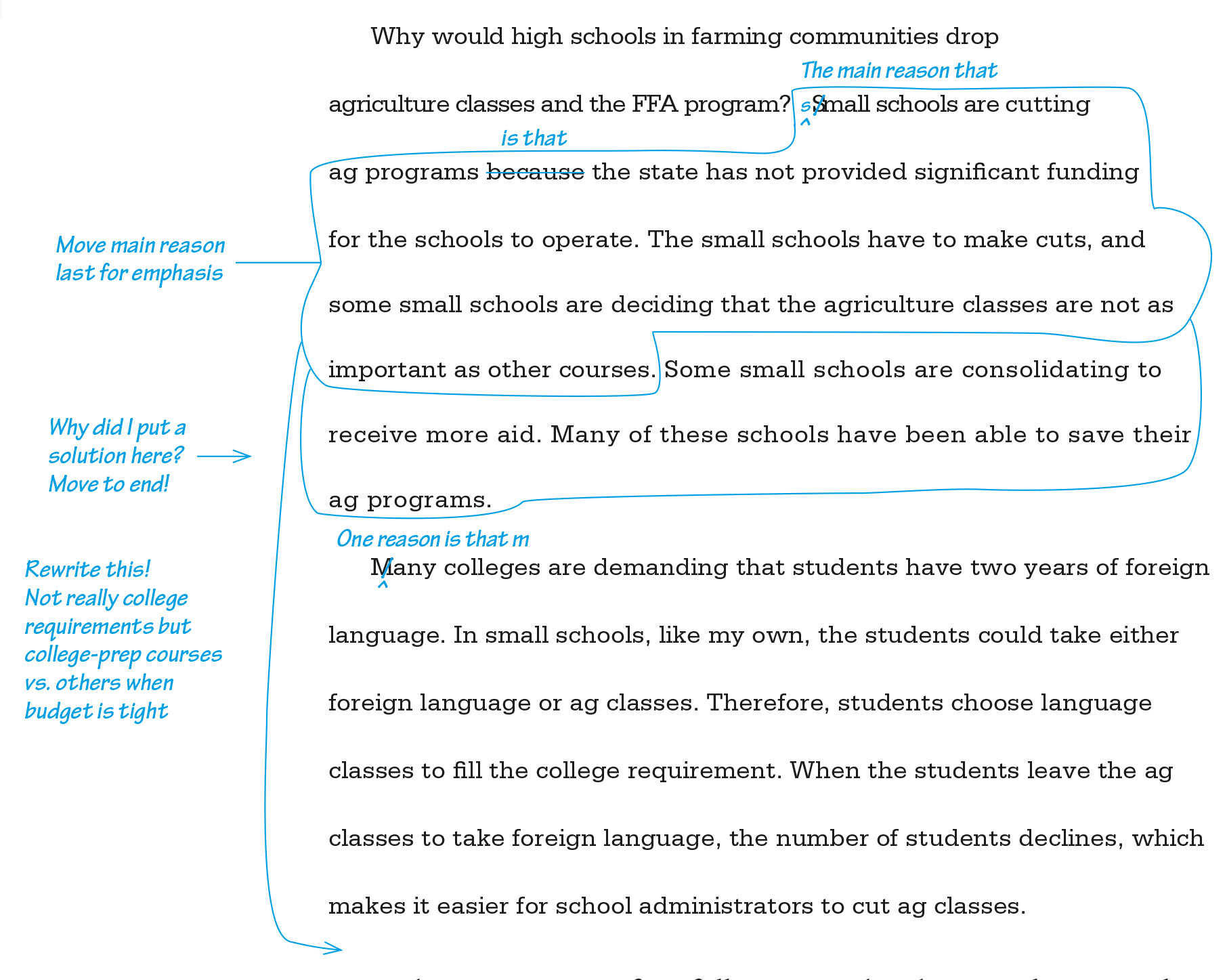

Reorganize for Unity and Coherence. When Heather Colbenson revised her first draft, she wanted to clarify the presentation of her problem.

Click here for accessible version of above content.

For strategies for achieving coherence, see Adding Cues and Connections in Ch. 21.

Her revised paper was more forcefully organized and more coherent, making it easier for readers to follow. The bridges between ideas were now on paper, not just in her mind.

191

Learning by Doing Revising for Clear Organization

Learning by Doing Revising for Clear Organization

Revising for Clear Organization

Check the organization of your draft against your plans and the two-part structure commonly used in proposals (see p. 187). Outline what you’ve actually done, not what you intended, to see your organization as readers will. Does your draft open with a sufficient overview for your audience? Do you state your actual proposal clearly? Does your draft progress from problem to solution without mixing ideas? Have you included elements appropriate for your audience? Reorganize and revise as needed. Exchange drafts with a classmate if you want a second opinion on organization.

Be Reasonable. Exaggerated claims for a solution will not persuade readers. Neither will oversimplifying the problem so the solution seems more workable. Don’t be afraid to express reasonable doubts about the completeness of your solution. If necessary, rethink both problem and solution.

For general questions for a peer editor, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Peer Response Proposing a Solution

Peer Response Proposing a Solution

Proposing a Solution

Ask several classmates or friends to review your proposal and solution, answering questions such as these:

What is your overall reaction to this proposal? Does it make you want to go out and do something about the problem?

Are you convinced that the problem is of concern to you? If not, why not?

Are you persuaded that the writer’s solution is workable? Why, or why not?

Has the writer paid enough attention to readers and their concerns?

Restate what you understand to be the proposal’s major points:

Problem

Explanation of problem and why it matters

Proposed solution

Explanation of proposal and its practicality

Reasons and procedure to implement proposal

Proposal’s advantages, disadvantages, and responses to other solutions

Final recommendation

If this paper were yours, what one thing would you work on?

REVISION CHECKLIST

Does your introduction invite the reader into the discussion?

Is your problem clear? How have you made it relevant to readers?

Have you clearly outlined the steps necessary to solve the problem?

Where have you demonstrated the benefits of your solution?

Have you considered other solutions before rejecting them for your own?

Have you anticipated the doubts readers may have about your solution?

Do you sound reasonable, willing to admit that you don’t know everything? If you sound preachy, have you overused should and must?

Have you avoided promising that your solution will do more than it can possibly do? Have you made believable predictions for its success?

192

For more on editing and proofreading strategies, see Editing and Proofreading in Ch. 23. For more on citing sources, see section E in the Quick Research Guide.

After you have revised your proposal, edit and proofread it. Carefully check the grammar, word choice, punctuation, and mechanics—and then correct any problems you find. If you have used sources, be sure that you have cited them correctly in your text and added a list of works cited.

Make sure your sentence structure helps you make your points clearly and directly. Using the active voice allows you to emphasize the actor (subject) performing the sentence’s action (verb). For example, the sentence “The dean should remedy the problem by spending money on prevention” explicitly identifies and emphasizes the actor (the dean) and does so succinctly. Using the passive voice, by contrast, results in a sentence that doesn’t specify the actor: “The problem should be remedied by spending money on prevention.” Readers may struggle to determine your intended focus—is it on the dean, or on the problem?

For more help, find the relevant checklist sections in the Quick Editing Guide. Also see the Quick Format Guide.

EDITING CHECKLIST

A6Is it clear what each pronoun refers to? Is any this or that ambiguous? Does each pronoun agree with its antecedent?

A1, A2Is your sentence structure correct? Have you avoided writing fragments, comma splices, or fused sentences?

C1Do your transitions and other introductory elements have commas after them, if these are needed?

D1, D2Have you spelled and capitalized everything correctly, especially names of people and organizations?