Finding Ideas

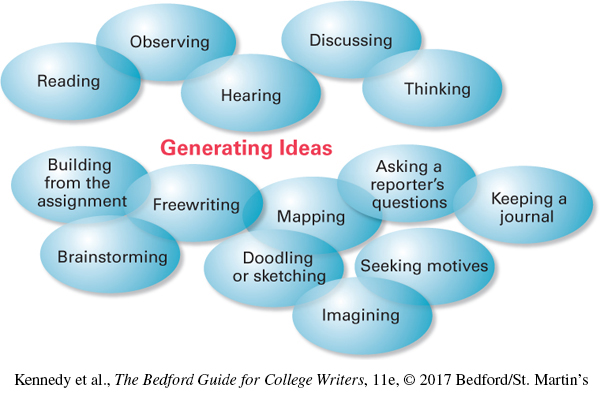

When you begin to write, ideas may appear effortlessly on the paper or screen, perhaps triggered by resources around you—something you read, see, hear, discuss, or think about. (See the top half of the graphic below.) But at other times you need idea generators, strategies to try when your ideas dry up. If one strategy doesn’t work for your task, try another. (See the lower half of the graphic.)

370

Building from Your Assignment

For more detail about this assignment, see Learning by Writing in Ch. 4.

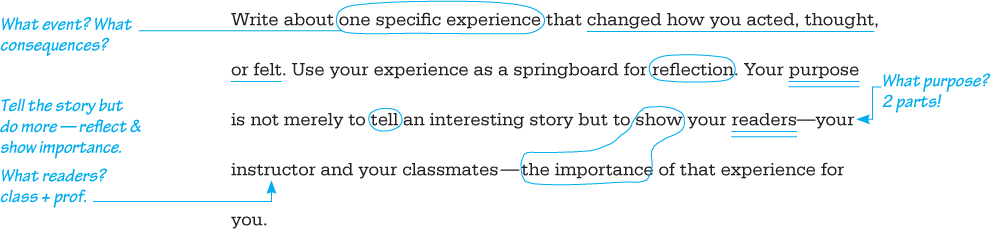

Learning to write is learning what questions to ask yourself. Your assignment may trigger this process, raising some questions and answering others. For example, Ben Tran jotted notes in his book as his instructor and classmates discussed his first assignment—recalling a personal experience.

The assignment clarified what audience to address and what purpose to set. Ben’s classmates asked about length, format, and due date, but Ben saw three big questions: Which experience should I pick? How did it change me? Why was it so important for me? Ben still didn’t know what he’d write about, but he had figured out the questions to tackle first.

Click here for accessible version of above content.

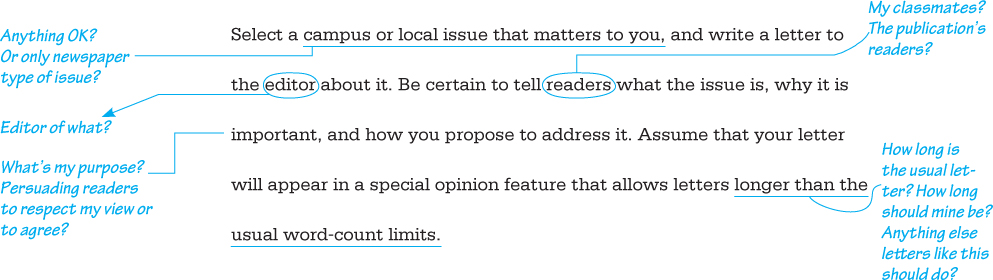

Sometimes assignments assume that you already know something critical—how to address a particular audience or what to include in some type of writing. When Amalia Blackhawk read her argument assignment, she jotted down questions to ask her instructor.

Click here for accessible version of above content.

Try these steps as you examine an assignment:

Read through the assignment once to discover its overall direction.

Read it again, marking information about your situation as a writer. Does the assignment identify or suggest your audience, your purpose in writing, the type of paper expected, the parts typical of that kind of writing, or the format required?

List the questions that the assignment raises for you. Exactly what do you need to decide—the type of topic to pick, the focus to develop, the issues or aspects to consider, or other guidelines to follow?

Finally, list any questions that the assignment doesn’t answer or ask you to answer. Ask your instructor about these questions.

371

Learning by Doing Building from Your Assignment

Learning by Doing Building from Your Assignment

Building from Your Assignment

Select an assignment from this book, another textbook, or another class, and make notes about it. Are there unanswered questions you want to clarify with your instructor? If so, make a list of these questions, and then exchange your list and assignment with a classmate. Make notes for your peer, suggesting possible answers or additional questions that might be posed to the instructor. Then compare responses.

Brainstorming

A brainstorm is a sudden insight or inspiration. As a writing strategy, brainstorming uses free association to stimulate a chain of ideas, often to personalize a topic and break it down into specifics. Start with a word or phrase, and spend a set period of time simply listing ideas as rapidly as possible. Write down whatever comes to mind with no editing or going back.

As a group activity, brainstorming gains from varied perspectives. At work, it can fill a specific need—finding a name for a product or an advertising slogan. In college, you can brainstorm with a few others or your entire class. Sit facing one another. Designate one person to record on paper, screen, or chalkboard whatever the others suggest. After several minutes of calling out ideas, look over the recorder’s list for useful results. Online, toss out ideas during a chat or post them for all to consider.

On your own, brainstorm to define a topic, generate an example, or find a title for a finished paper. Angie Ortiz brainstormed after her instructor assigned a paper (“Demonstrate from your experience how electronic technology affects our lives”). She wrote electronic technology on the page, set her alarm for fifteen minutes, and began to scribble.

Electronic technology

Cell phone, laptop, tablet. Plus smart TV, cable, DVDs. Too much?!

Always on call—at home, in car, at school. Always something playing.

Spend so much time in electronic world—phone calls, texting, social media. Cuts into time really hanging with friends—face-to-face time.

Less aware of my surroundings outside of the electronic world?

When her alarm went off, Angie took a break. After returning to her list, she crossed out ideas that did not interest her and circled her final promising question. A focus began to emerge: the capacity of the electronic world to expand information but reduce awareness.

372

When you want to brainstorm, try this advice:

Launch your thoughts with a key word or phrase. If you need a topic, try a general term (computer); if you need an example for a paragraph in progress, try specifics (financial errors computers make).

Set a time limit. Ten minutes (or so) is enough for strenuous thinking.

Rapidly list brief items. Stick to words, phrases, or short sentences that you can quickly scan later.

Don’t stop. Don’t worry about spelling, repetition, or relevance. Don’t judge, and don’t arrange: just produce. Record whatever comes to mind, as fast as you can. If your mind goes blank, keep moving, even if you only repeat what you’ve just written.

When you finish, circle or check anything intriguing. Scratch out whatever looks useless or dull. Then try some conscious organizing: Are any thoughts related? Can you group them? Does the group suggest a topic?

Learning by Doing Brainstorming

Learning by Doing Brainstorming

Brainstorming

From the following list, choose a subject that interests you, that you know something about, and that you’d like to learn more about—in other words, that you might like to write on.

| challenges/fears | the environment | health/fitness |

| dreams | family | pets |

| education | food | technology/social media |

| entertainment | friends | work |

For five minutes write as quickly as you can about your subject, listing everything that comes to mind about it, including all pertinent details. If your writing brings up a debatable issue (such as whether or not workplaces should offer flexible schedules), consider pros, cons, and alternative points of view. If it calls to mind an event (such as a memorable family occasion), list the details of the event in chronological order. Exchange your work with a peer, and see if you can add new ideas or insights to each other’s brainstorming.

Freewriting

To tap your unconscious by freewriting, simply write sentences without stopping for about fifteen minutes. The sentences don’t have to be grammatical, coherent, or stylish; just keep them flowing to unlock an idea’s potential.

For Ortiz’s brainstorming, scroll up to the "Brainstorming" section on this page.

Generally, freewriting is most productive if it has an aim—for example, finding a topic, a purpose, or a question you want to answer. Angie Ortiz wrote her topic at the top of a page—and then explored her rough ideas.

373

Electronic devices—do they isolate us? I chat all day online and by phone, but that’s quick communication, not in-depth conversation. I don’t really spend much time hanging with friends and getting to know what’s going on with them. I love listening to music on my phone on campus, but maybe I’m not as aware of my surroundings as I could be. I miss seeing things, like the new art gallery that I walk by every day. I didn’t even notice the new sculpture park in front! Then, at night, I do assignments on my computer, browse the Web, and watch some cable. I’m in my own little electronic world most of the time. I love technology, but what else am I missing?

Angie’s result wasn’t polished prose. Still, in a short time she produced a paragraph to serve as a springboard for her essay.

If you want to try freewriting, here’s what you do:

Write a sentence or two at the top of your page or file—the idea you plan to develop by freewriting.

Write without stopping for at least ten minutes. Express whatever comes to mind, even “My mind is blank,” until a new thought floats up.

Explore without censoring yourself. Don’t cross out false starts or grammar errors. Don’t worry about connecting ideas or finding perfect words. Use your initial sentences as a rough guide, not a straitjacket. New directions may be valuable.

Prepare yourself—if you want to. While you wait for your ideas to start racing, you may want to ask yourself some questions:

What interests you about the topic? What do you know about it that the next person doesn’t? What have you read, observed, or heard about it?

How might you feel about this topic if you were someone else (a parent, an instructor, a person from another country)?

Repeat the process, looping back to expand a good idea if you wish. Poke at the most interesting parts to see if they will further unfold:

What does that mean? If that’s true, what then? So what?

What other examples or evidence does this statement call to mind?

What objections might a reader raise? How might you answer them?

Learning by Doing Freewriting

Learning by Doing Freewriting

Freewriting

Select an idea from your current thinking or a brainstorming list. Write it at the top of a page or file, and freewrite for fifteen minutes. Share your freewriting with your classmates. If you wish, loop back to repeat this process.

374

Doodling or Sketching

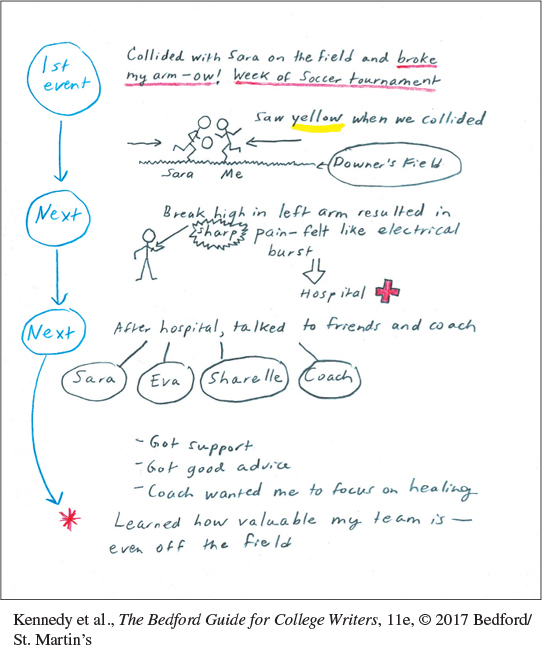

If you fill the margins of your notebooks with doodles, harness this artistic energy to generate ideas for writing. Elena Lopez began to sketch her collision with a teammate during a soccer tournament (Figure 19.1). She added stick figures, notes, symbols, and color as she outlined a series of events.

Try this advice as you develop ideas by doodling or sketching:

Give your ideas room to grow. Open a new file using a drawing program, doodle in pencil on a blank page, or sketch on a series of pages.

Concentrate on your topic, but welcome new ideas. Begin with a key visual in the center or at the top of a page. Add sketches or doodles as they occur to you to embellish, expand, define, or redirect your topic.

Add icons, symbols, colors, figures, labels, notes, or questions. Freely mix visuals and text, recording ideas without stopping to refine them.

Follow up on your discoveries. After a break, add notes to make connections, identify sequences, or convert visuals into descriptive sentences.

375

Learning by Doing Doodling or Sketching

Learning by Doing Doodling or Sketching

Doodling or Sketching

Start with a doodle or sketch that illustrates your topic. Add related events, ideas, or details to develop your topic visually. Share your material with classmates; use their observations to help you refine your direction as a writer.

Mapping

Mapping taps your visual and spatial creativity as you position ideas on the page, in a file, or with cloud software to show their relationships or relative importance. Ideas might radiate outward from a key term in the center, drop down from a key word at the top, sprout upward from a root idea, branch out from a trunk, flow across a page or screen in a chronological or causal sequence, or follow a circular, spiral, or other form.

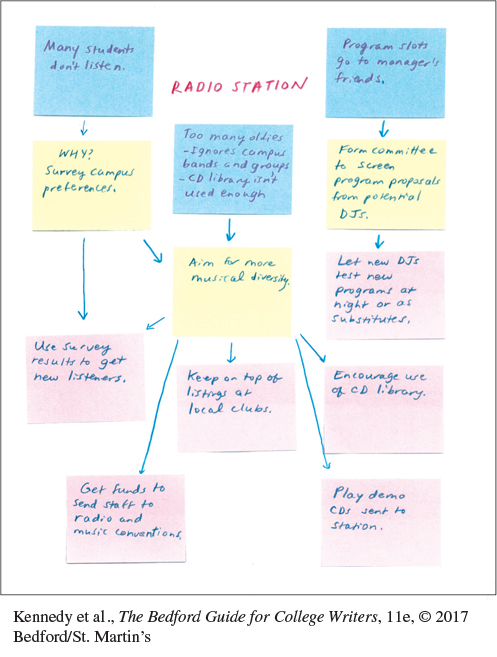

Andrew Choi used mapping to gather ideas for his proposal for revitalizing the campus radio station (Figure 19.2). He noted ideas on colored sticky notes—blue for problems, yellow for solutions, and pink for implementation details. Then he moved the sticky notes around on a blank page, arranging them as he connected ideas.

Here are some suggestions for mapping:

Allow space for your map to develop. Open a new file, try posterboard for arranging sticky notes or cards, or use a large page for notes.

Begin with a topic or key idea. Using your imagination, memory, class notes, or reading, place a key word at the center or top of a page.

Add related ideas, examples, issues, or questions. Quickly and spontaneously place these points above, below, or beside your key word.

Refine the connections. As your map evolves, use lines, arrows, or loops to connect ideas; box or circle them to focus attention; add colors to relate points or to distinguish source materials from your own ideas.

After a break, continue mapping to probe one part more deeply, refine the structure, add detail, or build an alternate map from a different viewpoint. Also try mapping to develop graphics that present ideas in visual form.

376

Learning by Doing Mapping

Learning by Doing Mapping

Mapping

Start with a key word or idea that you know about. Map related ideas, using visual elements to show how they connect. Share your map with classmates, and then use their questions or comments to refine your mapping.

Imagining

Your imagination is a valuable resource for exploring possibilities—analyzing an option, evaluating an alternative, or solving a problem—to discover surprising ideas, original examples, and unexpected relationships.

377

Suppose you asked, “What if the average North American lived more than a century?” No doubt many more people would be old. How would that shift affect doctors, nurses, and medical facilities? How might city planners respond? What would the change mean for shopping centers? For television programming? For leisure activities? For Social Security?

Use some of the following strategies to unleash your imagination:

Speculate about changes, alternatives, and options. What common assumption might you question or deny? What deplorable condition would you remedy? What changes in policy, practice, or attitude might avoid problems? What different paths in life might you take?

Shift perspective. Experiment with a different point of view. How would someone on the opposing side respond? A plant, an animal, a Martian? Shift the debate (whether retirees, not teens, should be allowed to drink) or the time (present to past or future).

Envision what might be. Join the others who have imagined a utopia (an ideal state) or an anti-utopia by envisioning alternatives—a better way of treating illness, electing a president, or ordering a chaotic jumble.

For more about analysis and synthesis, see Reading on Literal and Analytical Levels in Ch. 2.

Synthesize. Synthesis (generating new ideas by combining previously separate ideas) is the opposite of analysis (breaking ideas down into component parts). Synthesize to make fresh connections, fusing materials—perhaps old or familiar—into something new.

Learning by Doing Imagining

Learning by Doing Imagining

Imagining

Begin with a problem that cries out for a solution, a condition that requires a remedy, or a situation that calls for change. Ask “What if?” or start with “Suppose that” to trigger your imagination. Share ideas with your classmates.

Asking a Reporter’s Questions

Journalists, assembling facts to write a news story, ask themselves six simple questions—the five W’s and an H:

| Who? | Where? | Why? |

| What? | When? | How? |

In the lead, or opening paragraph, of a good news story, the writer tries to condense the whole story into a sentence or two, answering all six questions.

A giant homemade fire balloon [what] startled residents of Costa Mesa [where] last night [when] as Ambrose Barker, 79, [who] zigzagged across the sky at nearly 300 miles per hour [how] in an attempt to set a new altitude record [why].

Later in the news story, the reporter will add details, using the six basic questions to generate more about what happened and why.

378

For your college writing, use these questions to generate details. They can help you explore the significance of a childhood experience, analyze what happened at a moment in history, or investigate a campus problem. Don’t worry if some go nowhere or are repetitious. Later you’ll weed out irrelevant points and keep those that look promising.

For a topic that is not based on your personal experience, you may need to do reading or interviewing to answer some of the questions. Take, for example, the topic of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and notice how each question can lead to further questions.

Who was John F. Kennedy? What kind of person was he? What kind of president? Who was with him when he was killed? Who was nearby?

What happened to Kennedy? What events led up to the assassination? What happened during it? What did the media do? What did people across the country do? What did someone who remembers this event do?

Where was Kennedy assassinated—city, street, vehicle, seat? Where was he going? Where did the shots likely come from? Where did they hit him? Where did he die?

When was he assassinated—day, month, year, time? When did Kennedy decide to go to this city? When—precisely—were the shots fired? When did he die? When was a suspect arrested?

Why was Kennedy assassinated? What are some of theories? What solid evidence is available? Why has this event caused controversy?

How was Kennedy assassinated? How many shots were fired? Specifically what caused his death? How can we get at the truth of this event?

Learning by Doing Asking a Reporter’s Questions

Learning by Doing Asking a Reporter’s Questions

Asking a Reporter’s Questions

Choose one of the following topics, or use one of your own:

A memorable event in history or in your life

A concert or other performance that you have attended

An accomplishment on campus or an occurrence in your city

An important speech or a proposal for change

A questionable stand someone has taken

Answer the six reporter’s questions about the topic. Then write a sentence or two synthesizing the answers to the six questions. Incorporate that sentence into an introductory paragraph for an essay that you might write later.

Seeking Motives

For more on writing about literature, see Ch. 13.

In much college writing, you will try to explain motives behind human behavior. In a history paper, you might consider how George Washington’s conduct shaped the presidency. In a literature essay, you might analyze the motives of Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter. Because people, including characters in fiction, are so complex, this task is challenging.

379

To understand any human act, according to philosopher-critic Kenneth Burke, you can break it down into five components, a pentad, and ask questions about each one. Burke’s pentad overlaps the reporter’s questions but also can show how components of a human act affect one another, taking you deeper into motives. Suppose you are writing a political-science paper on President Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ), sworn in as president right after President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. A year later, he was elected to the post by a landslide. By 1968, however, he had decided not to run for a second term. You use Burke’s pentad to investigate why.

The act: What was done?

Announcing the decision to leave office without standing for reelection.

The actor: Who did it?

President Johnson.

The agency: What means did the person use to make it happen?

A televised address to the nation.

The scene: Where, when, and under what circumstances did it happen?

Washington, DC, March 31, 1968. Protesters against the Vietnam War were gaining influence. The press was increasingly critical of the war. Senator Eugene McCarthy, an antiwar candidate for president, had made a strong showing against LBJ in the New Hampshire primary.

The purpose or motive for acting: What could have made the person do it?

LBJ’s motives might have included avoiding probable defeat, escaping further personal attacks, sparing his family, making it easier for his successor to pull out of the war, and easing dissent among Americans.

Next, you can pair Burke’s five components and ask about the pairs:

| actor to act | act to scene | scene to agency |

| actor to scene | act to agency | scene to purpose |

| actor to purpose | act to purpose | agency to purpose |

| PAIR | actor to agency |

| QUESTION | What did LBJ [actor] have to do with his televised address [agency]? |

| ANSWER | Commanding the attention of a vast audience, LBJ must have felt in control—though his ability to control the situation in Vietnam was slipping. |

Not all the paired questions will prove fruitful; some may not even apply. But one or two might reveal valuable connections and start you writing.

380

Learning by Doing Seeking Motives

Learning by Doing Seeking Motives

Seeking Motives

Choose a puzzling action—perhaps something you, a family member, or a friend has done; a decision of a political figure; or something in a movie, on television, or in a book. Apply Burke’s pentad to seek motives for the action. If you wish, also pair up components. When you believe you understand the individual’s motivation, write a paragraph explaining the action, and share it with classmates.

Keeping a Journal

For ideas about keeping a reading journal, see Reading on Literal and Analytical Levels.

Journal writing richly rewards anyone who engages in it regularly. You can write anywhere or anytime: all you need is a few minutes to record an entry and the willingness to set down what you think and feel. Your journal will become a mine studded with priceless nuggets—thoughts, observations, reactions, and revelations that are yours for the taking. As you write, you can rifle your well-stocked journal for topics, insights, examples, and other material. The best type of journal is the one that’s useful to you.

Reflective Journals. When you write in your journal, put less emphasis on recording what happened, as you would in a diary, than on reflecting about what you do or see, hear or read, learn or believe. An entry can be a list or an outline, a paragraph or an essay, a poem or a letter you don’t intend to send. Describe a person or a place, set down a conversation, or record insights into actions. Consider your pet peeves, fears, dreams, treasures, or moral dilemmas. Use your experience as a writer to nourish and inspire your writing, recording what worked, what didn’t, and how you reacted to each.

For more on responding to a reading, see Ch. 2.

Responsive Journals. Sometimes you respond to something in particular—your assigned reading, a classroom discussion, a movie, a conversation, or an observation. Faced with a long paper, you might assign yourself a focused response journal so you have plenty of material to use.

Warm-Up Journals. To prepare for an assignment, you can group ideas, scribble outlines, sketch beginnings, capture stray thoughts, record relevant material. Of course, a quick comment may turn into a draft.

E-Journals. Once you create a file and make entries by date or subject, you can record ideas, feelings, images, memories, and quotations. You will find it easy to copy and paste inspiring e-mail, quotations from Web pages, or images and sounds. Always identify the source of copied material so that you won’t later confuse it with your original writing.

Blogs. Like traditional journals, blogs aim for frank, honest, immediate entries. Unlike journals, they often explore a specific topic and may be available publicly on the Web or privately by invitation. Especially in an online class, you might blog about your writing or research processes.

381

Learning by Doing Keeping a Journal

Learning by Doing Keeping a Journal

Keeping a Journal

Keep a journal for at least a week. Each day record your thoughts, feelings, observations, and reactions. Reflect on what happens, and respond to what you read, including selections from this book. Then bring your journal to class, and read aloud to your classmates the entry you like best.