Purpose and Audience

At any moment in the writing process, two questions are worth asking:

Writing for a Reason

For more on using your purpose for planning, see Shaping Your Topic for Your Purpose and Your Audience in Ch. 20, and for revising, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Like most college writing assignments, every assignment in this book asks you to write for a definite reason. For example, you’ll recall a memorable experience in order to explain its importance for you; you’ll take a stand on a controversy in order to convey your position and persuade readers to respect it. Be careful not to confuse the sources and strategies you apply in these assignments with your ultimate purpose for writing.“To compare and contrast two things” is not a very interesting purpose; “to compare and contrast two Web sites in order to explain which is more reliable” implies a real reason for writing. In most college writing, your purpose will be to explain something to your readers or to convince them of something.

To sharpen your concentration on your purpose, ask yourself from the start: What do I want to do? And, in revising, Did I do what I meant to do? These practical questions will help you slice out irrelevant information and remove other barriers to getting your paper where you want it to go.

Learning by Doing Considering Purpose

Learning by Doing Considering Purpose

Considering Purpose

Imagine that you are in the following writing situations. For each, write a sentence or two summing up your purpose as a writer.

The instructor in your psychology course has assigned a paragraph about the meanings of three essential terms in your readings.

You’re upset about a change in financial aid procedures and plan to write a letter asking the financial aid director to remedy the problem.

12

You’re starting a blog about your first year at college so your extended family can envision the environment and share your experiences.

Your supervisor wants you to write an article about the benefits of a new company service for the customer newsletter.

Your Facebook profile seemed appropriate last year, but you want to revise it now that you’re attending college and have a job with future prospects.

| General Audience | College Instructor | Work Supervisor | Campus Friend | |

| Relationship to You | Imagined but not known personally | Known briefly in a class context | Known for some time in a job context | Known in campus and social contexts |

| Reason for Reading Your Writing | Curious attitude and interest in your topic assumed | Professional responsibility for your knowledge and skills | Managerial interest in and reliance on your job performance | Personal interest based on shared circumstances |

| Knowledge about Your Topic | Level of awareness assumed and gaps addressed with logical presentation | Well informed about college topics but wants to see what you know | Informed about the business and expects reliable information from you | Friendly but may or may not be informed beyond social interests |

| Forms and Formats Expected | Essay, article, letter, report, or other format | Essay, report, research paper, or other academic format | Memo, report, Web page, e-mail, or letter using company format | Notes, blog entries, social networking, or other informal messages |

| Language and Style Expected | Formal, using clear words and sentences | Formal, following academic conventions | Appropriate for advancing you and the company | Informal, using abbreviations, phrases, and slang |

| Attitude and Tone Expected | Interested and thoughtful about the topic | Serious and thoughtful about the topic and course | Respectful, showing reliability and work ethic | Friendly and interested in shared experiences |

| Amount of Detail Expected | Enough to inform or persuade general readers | Enough sound or research-based evidence to support your thesis | General or technical information as needed | Much detail or little, depending on the topic |

Writing for Your Audience

13

For more on planning for your readers, see Shaping Your Topic for Your Purpose and Your Audience in Ch. 20. For more on revising for them, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Your audience may or may not be defined in your assignment. Consider the following examples:

| ASSIGNMENT 1 | Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of homeschooling. |

| ASSIGNMENT 2 | In a letter to parents of school-aged children, discuss the advantages and disadvantages of homeschooling. |

If your assignment defines an audience, as the second example does, you need to think about how to approach those readers and what to assume about their views. For example, what points would you include in a discussion aimed at parents? How would you organize your ideas? Would you discuss advantages or disadvantages first? On the other hand, how might your approach differ if the assignment read this way?

| ASSIGNMENT 3 | In a newsletter article for teachers, discuss the advantages and disadvantages of homeschooling. |

Audiences may be identified by characteristics, such as role (parents) or occupation (teachers), that suggest values to which a writer might appeal. As the chart above suggests, you can analyze preferences, biases, and concerns of readers to engage and influence them more successfully.

AUDIENCE CHECKLIST

Who are your readers? What is their relationship to you?

What do they know about this topic? What do you want them to learn?

How much detail will they want to read about this topic?

What objections are they likely to raise as they read? How can you anticipate and overcome their objections?

What is likely to convince them? What’s likely to offend them?

What tone and style would most effectively influence them?

Learning by Doing Considering Audience

Learning by Doing Considering Audience

Considering Audience

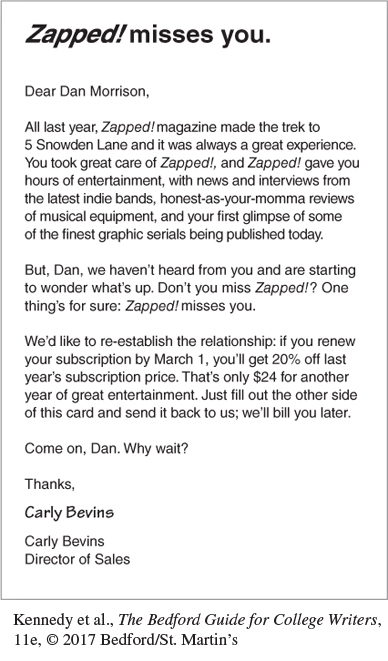

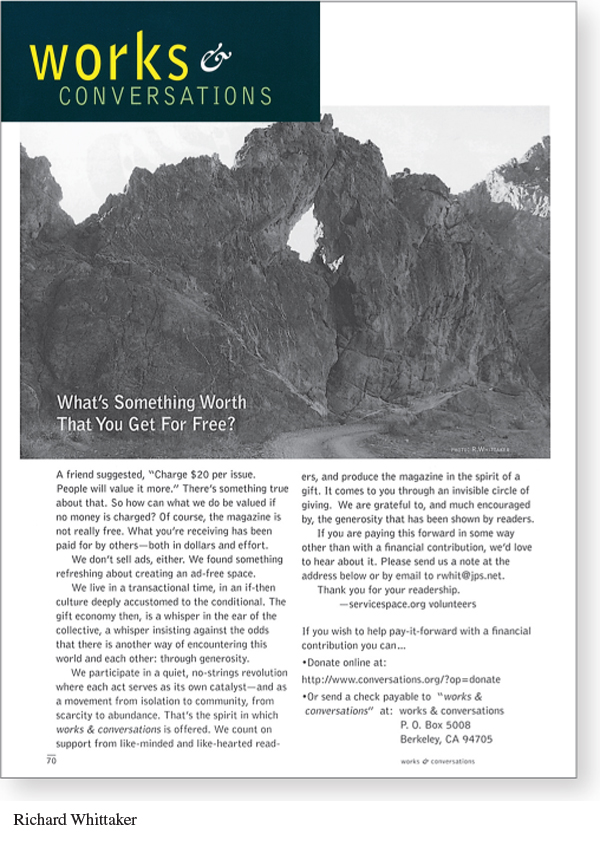

Read the notices on page 14 directed to subscribers of two magazines, Zapped! and works & conversations. Examine the style, tone, language, sequence of topics, and other features of each appeal. Write a short paragraph about each notice, explaining what you can conclude about the letter’s target audience and its appeal to that audience.

14

Figure 1.1: Figure 1.1 Renewal letter from Zapped!

Bedford/St. Martin’s.

|

Figure 1.2: Figure 1.2 Appeal to readers of works & conversations.

Richard Whittaker

|

Targeting a College Audience

Many of your college assignments may assume that you are addressing general college readers, represented by your instructor and possibly your classmates. Such readers typically expect clear, logical writing with supporting evidence to explain or persuade. Of course, the format, approach, or evidence may differ by field. For example, biologists might expect the findings from your experiment, while literature specialists might look for relevant quotations from the novel you’re analyzing.

COLLEGE AUDIENCE CHECKLIST

How has your instructor advised you to write for readers? What criteria related to audience will be used for grading your papers?

What do the assigned readings in your course assume about an audience? Has your instructor recommended models or sample readings?

15

What topics intrigue readers in the course area? What problems do they want to solve? How do they want to solve them?

How is writing in the course area commonly organized? For example, do writers tend to follow a persuasive pattern—introducing the issue, stating an assertion or a claim, backing the claim with evidence, acknowledging other views, and concluding? Or do they use conventional headings—perhaps Abstract, Introduction, Methodology, Findings, and Discussion?

For more strategies for future college writing, see Ch. 24.

What evidence typically supports ideas or interpretations—facts and statistics, quotations from texts, summaries of research, experimental findings, observations, or interviews?

What style, tone, and level of formality do writers in the field use?

Learning by Doing Writing for Different Audiences

Learning by Doing Writing for Different Audiences

Writing for Different Audiences

Imagine that you’ve been in a minor car accident. Write out the descriptions of the incident you’d give to the following audiences: a close friend, your parents, a police officer, and the insurance company. How does the language change, if at all? To whom are certain details accentuated or downplayed? Write a paragraph or more to reflect about the differences between the stories.