Organizing Your Ideas

When you organize an essay, you select an order for the parts that makes sense and shows your readers how the ideas are connected. Often your organization will not only help a reader follow your points but also reinforce your emphases by moving from beginning to end or from least to most significant, as the table below illustrates.

Grouping Your Ideas

While exploring a topic, you will usually find a few ideas that seem to belong together—two facts on New York traffic jams, four actions of New York drivers, three problems with New York streets. But similar ideas seldom appear together in your notes because you did not discover them all at the same time. For this reason, you need to sort your ideas into groups and arrange them in sequences. Here are six ways to work:

Rainbow connections. List the main points you’re going to express. Highlight points that go together with the same color. When you write, follow the color code, and integrate related ideas at the same time.

Emphasizing ideas. Make a copy of your file of ideas or notes. Use your software tools to highlight, categorize, and shape your thinking by grouping or distinguishing ideas. Mark similar or related ideas in the same way; call out major points. Then move related materials into groups.

Highlighting Adding bullets

Boxing Numbering

Showing color Changing fonts Using bold, italics, underlining Varying print sizes 394

Organization Movement Typical Use Example Spatial Left to right, right to left, bottom to top, top to bottom, front to back, outside to inside

Describing a place, a scene, or an environment

Describing a person’s physical appearance

Describe an ocean vista, moving from the tidepools on the rocky shore to the plastic buoys floating offshore to the sparkling water meeting the sunset sky.

Chronological What happens first, second, and next, continuing until the end

Narrating an event

Explaining steps in a procedure

Explaining the development of an idea or a trend

Narrate the events that led up to an accident: leaving home late, stopping for an errand, checking messages while rushing along the highway, racing up to the intersection.

Logical General to specific (or the reverse), least important to most, cause to effect, problem to solution

Explaining an idea

Persuading readers to accept a stand, a proposal, or an evaluation

Analyze the effects of last year’s storms by selecting four major consequences, placing the most important one last for emphasis.

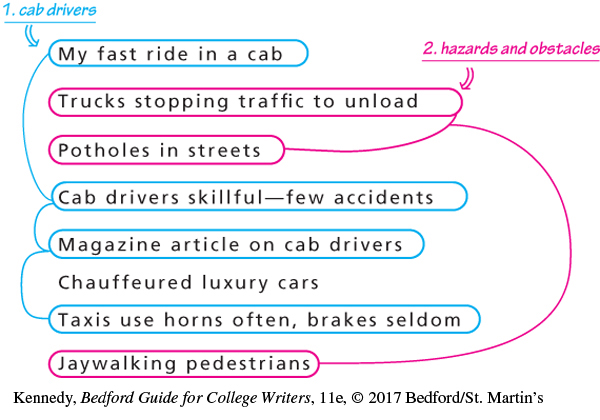

Linking. List major points, and then draw lines (in color if you wish) to link related ideas. Figure 20.1 illustrates a linked list for an essay on Manhattan driving. The writer has connected related points, numbered their sequence, and supplied each group with a heading. Each heading will probably inspire a topic sentence to introduce a major division of the essay. Because one point, chauffeured luxury cars, failed to relate to any other, the writer has a choice: drop it or develop it.

Figure 20.1: Figure 20.1 The linking method for grouping ideas.

Figure 20.1: Figure 20.1 The linking method for grouping ideas.Solitaire. Collect notes and ideas on roomy (5-by-8-inch) file cards, especially to write about literature or research. To organize, spread out the cards; arrange and rearrange them. When each idea seems to lead to the next, gather the cards into a deck in this order. As you write, deal yourself a card at a time, and turn its contents into sentences.

Slide show. Use presentation software to write your notes and ideas on “slides.” When you’re done, view your slides one by one or as a collection. Sort your slides into the most promising order.

395

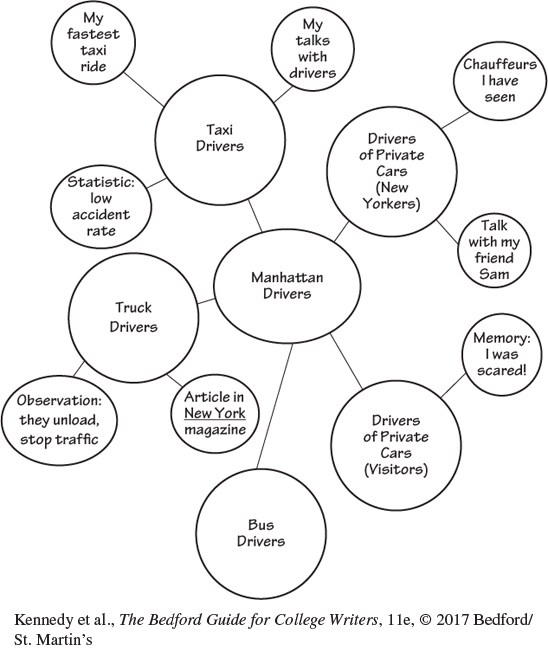

Clustering. Clustering is a visual method for generating as well as grouping ideas. In the middle of a page, write your topic in a word or a phrase. Then think of the major divisions into which you might break your topic. For an essay on Manhattan drivers, your major divisions might be types of drivers: (1) taxi drivers, (2) bus drivers, (3) truck drivers, (4) New York drivers of private cars, and (5) out-of-town drivers of private cars. Arrange these divisions around your topic, circle them, and draw lines out from the major topic. You now have a rough plan for an essay. (See Figure 20.2.)

Figure 20.2: Figure 20.2 The clustering method for grouping ideas.

Figure 20.2: Figure 20.2 The clustering method for grouping ideas.

Around each division, make another cluster of details you might include—examples, illustrations, facts, statistics, opinions. Circle each specific item, connect it to the appropriate type of driver, and then expand the details into a paragraph. This technique lets you know where you have enough specific information to make your paper clear and interesting—and where you don’t. If one subtopic has no small circles around it (such as “Bus Drivers” in Figure 20.2), either add specifics to expand it or drop it.

Outlining

A familiar way to organize is to outline. A written outline, whether brief or detailed, acts as a map that you make before a journey. It shows where to leave from, where to stop along the way, and where to arrive. If you forget where you are going or what you want to say, you can consult your outline to get back on track. When you turn in your essay, your instructor may request an outline as both a map for readers and a skeletal summary.

For more on thesis statements, see Stating and Using a Thesis.

Some writers like to begin with a working thesis. If it’s clear, it may suggest how to develop or expand an outline, allowing the plan for the paper to grow naturally from the idea behind it.

396

For more on using outlining for revision, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Others prefer to start with a loose informal outline—perhaps just a list of points to make. If readers find your papers mechanical, such an outline may free up your writing.

Still others, especially for research papers or complicated arguments, like to lay out a complex job very carefully in a detailed formal outline. If readers find your writing disorganized and hard to follow, this more detailed plan might be especially useful.

Thesis-Guided Outlines. Your working thesis may identify ideas you can use to organize your paper. (If it doesn’t, you may want to revise your thesis and then return to your outline or vice versa.) Suppose you are assigned an anthropology paper on the people of Melanesia. You focus on this point:

Working Thesis: Although the Melanesian pattern of family life may look strange to Westerners, it fosters a degree of independence that rivals our own.

If you lay out your ideas in the same order that they follow in the two parts of this thesis statement, your simple outline suggests an essay that naturally falls into two parts—features that seem strange and admirable results.

397

Features that appear strange to Westerners

A woman supported by her brother, not her husband

Trial marriages common

Divorce from her children possible for any mother

Admirable results of system

Wives not dependent on husbands for support

Divorce between mates uncommon

Greater freedom for parents and children

When you create a thesis-guided outline, look for the key element of your working thesis. This key element can suggest both a useful question to consider and an organization, as the table below illustrates.

Informal Outlines. For in-class writing, brief essays, and familiar topics, a short or informal outline, also called a scratch outline, may serve your needs. Jot down a list of points in the order you plan to make them. Use this outline, for your eyes only, to help you get organized, stick to the point, and remember ideas under pressure. The following example outlines a short paper explaining how outdoor enthusiasts can avoid illnesses carried by unsafe drinking water. It simply lists the methods for treating potentially unsafe water that the writer plans to explain.

Working Thesis: Campers and hikers need to ensure the safety of the water that they drink from rivers or streams.

Introduction: Treatments for potentially unsafe drinking water

Small commercial filter

Remove bacteria and protozoa including salmonella and E. coli

Use brands convenient for campers and hikers

Chemicals

Use bleach, chlorine, or iodine

Follow general rule: 12 drops per gallon of water

Boiling

Boil for 5 minutes (Red Cross) to 15 minutes (National Safety Council)

Store in a clean, covered container

Conclusion: Using one of three methods of treating water, campers and hikers can enjoy safe water from natural sources.

This simple outline could easily fall into a five-paragraph essay or grow to eight paragraphs—introduction, conclusion, and three pairs of paragraphs in between. You won’t know how many you’ll need until you write.

398

| Sample Thesis Statement | Type of Key Element | Examples of Key Element | Question You Might Ask | Organization of Outline |

| A varied personal exercise program has four main advantages. | Plural word | Words such as benefits, advantages, teenagers, or reasons | What are the types, kinds, or examples of this word? | List outline headings based on the categories or cases you identify. |

| Wylie’s interpretation of Van Gogh’s last paintings unifies aesthetics and psychology. | Key word identifying an approach or vantage point | Words such as claim, argument, position, interpretation, or point of view | What are the parts, aspects, or elements of this approach? | List outline headings based on the components that you identify. |

| Preparing a pasta dinner for surprise guests can be an easy process. | Key word identifying an activity | Words such as preparing, harming, or improving | How is this activity accomplished, or how does it happen? | Supply a heading for each step, stage, or element that the activity involves. |

| Although the new wetland preserve will protect only some wildlife, it will bring several long-term benefits to the region. | One part of the sentence subordinate to another | Sentence part beginning with a qualification such as despite, because, since, or although | What does the qualification include, and what does the main statement include? | Use a major heading for the qualification and another for the main statement. |

| When Sandie Burns arrives in her wheelchair at the soccer field, other parents soon see that she is a typical soccer mom. | General evaluation that assigns a quality or value to someone or something | Evaluative words such as typical, unusual, valuable, notable, or other specific qualities | What examples, illustrations, or clusters of details will show this quality? | Add a heading for each extended example or each group of examples or details you want to use. |

| In spite of these tough economic times, the student senate should strongly recommend extended hours for the computer lab. | Claim or argument advocating a certain decision, action, or solution | Words such as should, could, might, ought to, need to, or must | Which reasons and evidence will justify this opinion? Which will counter the opinions of others who disagree with it? | Provide a heading for each major justification or defensive point; add headings for countering reasons. |

399

An informal outline can be even briefer than the preceding one. To answer an exam question or prepare a very short paper, your outline might be no more than an outer plan—three or four phrases jotted in a list:

Isolation of region

Tradition of family businesses

Growth of electronic commuting

The process of making an informal outline can help you figure out how to develop your ideas. Say you plan a “how-to” essay analyzing the process of buying a used car, beginning with this thesis:

Working Thesis: Despite traps that await the unwary, preparing yourself before you shop can help you find a good used car.

The key word here is preparing. Considering how the buyer should prepare before shopping for a used car, you’re likely to outline several ideas:

Read car blogs, car magazines, and Consumer Reports.

Check craigslist, dealer sites, and classified ads.

Make phone calls to several dealers.

Talk to friends who have bought used cars.

Know what to look and listen for when you test-drive.

Have a mechanic check out any car before you buy it.

After some horror stories about people who got taken by car sharks, you can discuss, point by point, your advice. You can always change the sequence, add or drop an idea, or revise your thesis as you go along.

Learning by Doing Moving from Outline to Thesis

Learning by Doing Moving from Outline to Thesis

Moving from Outline to Thesis

Based on each of the following informal outlines, write a thesis statement expressing a possible slant, attitude, or point (even if you aren’t sure that the position is entirely defensible). Compare thesis statements with classmates. What similarities and differences do you find? How do you account for these?

Smartphones

Get the financial and service plans of various smartphone companies.

Read the phone contracts as well as the promotional offers.

Look for the time period, flexibility, and cancellation provisions.

Check the display, keyboard, camera, apps, and other features.

Popular Mystery Novels

Both Tony Hillerman and Margaret Coel have written mysteries with Native American characters and settings.

Hillerman’s novels feature members of the Navajo Tribal Police.

400

Coel’s novels feature a female attorney who is an Arapaho and a Jesuit priest at the reservation mission who grew up in Boston.

Hillerman’s stories take place mostly on the extensive Navajo Reservation in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

Coel’s are set mostly on the large Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.

Hillerman and Coel try to convey tribal culture accurately, although their mysteries involve different tribes.

Both also explore similarities, differences, and conflicts between Native American cultures and the dominant culture.

Downtown Playspace

Downtown Playspace has financial and volunteer support but needs more.

Statistics show the need for a regional expansion of options for children.

Downtown Playspace will serve visitors at the Children’s Museum and local children in Head Start, preschool, and elementary schools.

It will combine an outdoor playground with indoor technology space.

Land and a building are available, but both require renovation.

Formal Outlines. A formal outline is an elaborate guide, built with time and care, for a long, complex paper. Because major reports, research papers, and senior theses require so much work, some professors and departments ask a writer to submit a formal outline at an early stage and to include one in the final draft. A formal outline shows how ideas relate to one another—which ones are equal and important (coordinate) and which are less important (subordinate). It clearly and logically spells out where you are going. If you outline again after writing a draft, you can use the revised outline to check your logic then as well, perhaps revealing where to revise.

When you make a full formal outline, follow these steps:

Place your thesis statement at the beginning.

List the major points that support and develop your thesis, labeling them with roman numerals (I, II, III).

Break down the major points into divisions with capital letters (A, B, C), subdivide those using arabic numerals (1, 2, 3), and subdivide those using small letters (a, b, c). Continue until your outline is fully developed. If a very complex project requires further subdivision, use arabic numerals and small letters in parentheses.

For more on parallelism, see section B in the Quick Editing Guide.

Indent each level of division in turn: the deeper the indentation, the more specific the ideas. Align like-numbered or -lettered headings under one another.

Cast all headings in parallel grammatical form: phrases or sentences, but not both in the same outline.

For more on analysis and division, see Analyzing a Subject in Ch. 22.

CAUTION: Because an outline divides or analyzes ideas, some readers and instructors disapprove of categories with only one subpoint, reasoning that you can’t divide anything into one part. Let’s say that your outline on earthquakes lists a 1 without a 2:

D. Probable results of an earthquake include structural damage.

House foundations crack.

401

Logically, if you are going to discuss the probable results of an earthquake, you need to include more than one result:

D. Probable results of an earthquake include structural damage.

House foundations crack.

Road surfaces are damaged.

Water mains break.

Not only have you now come up with more points, but you have also emphasized the one placed last.

A formal topic outline for a long paper might include several levels of ideas, as this outline for Linn Bourgeau’s research paper illustrates. Such an outline can help you work out both a persuasive sequence for the parts of a paper and a logical order for any information from sources.

Crucial Choices: Who Will Save the Wetlands If Everyone Is at the Mall?

Working Thesis: Federal regulations need to foster state laws and educational requirements that will help protect the few wetlands that are left, restore as many as possible of those that have been destroyed, and take measures to improve the damage from overdevelopment.

Nature’s ecosystem

Loss of wetlands nationally

Loss of wetlands in Illinois

More flooding and poorer water quality

Lost ability to prevent floods, clean water, and store water

Need to protect humankind

Dramatic floods

Midwestern floods in 1993 and 2011

Lost wetlands in Illinois and other states

Devastation in some states

Cost in dollars and lives

Deaths during recent flooding

Costs in millions of dollars a year

Flood prevention

Plants and soil

Floodplain overflow

Wetland laws

Inadequately informed legislators

Watersheds

Interconnections in natural water systems

Water purification

Wetlands and water

Pavement and lawns

Need to save wetlands

New federal laws

Reeducation about interconnectedness

Ecology at every grade level

Education for politicians, developers, and legislators

Choices in schools, legislature, and people’s daily lives

402

A topic outline may help you work out a clear sequence of ideas but may not elaborate or connect them. Although you may not be sure how everything will fit together until you write a draft, you may find that a formal sentence outline clarifies what you want to say. It also moves you a step closer to drafting topic sentences and paragraphs even though you would still need to add detailed information. Notice how this sentence outline for Linn Bourgeau’s research paper expands her ideas.

Crucial Choices: Who Will Save the Wetlands If Everyone Is at the Mall?

Working Thesis: Federal regulations need to foster state laws and educational requirements that will help protect the few wetlands that are left, restore as many as possible of those that have been destroyed, and take measures to improve the damage from overdevelopment.

Each person, as part of nature’s ecosystem, chooses how to interact with nature, including wetlands.

The nation has lost over half its wetlands since Columbus arrived.

Illinois has lost even more by legislating and draining them away.

Destroying wetlands creates more flooding and poorer water quality.

The wetlands could prevent floods, clean the water supply, and store water.

The wetlands need to be protected because they protect and serve humankind.

Floods are dramatic and visible consequences of not protecting wetlands.

The midwestern floods of 1993 and 2011 were disastrous.

Illinois and other states had lost their wetlands.

Those states also suffered the most devastation.

The cost of flooding can be tallied in dollars spent and in lives lost.

Nearly thirty people died in floods between 1995 and 2011.

Flooding in 2011 cost Illinois about $216 million.

Preventing floods is a valuable role of wetlands.

Plants and soil manage excess water.

The Mississippi River floodplain was reduced from 60 days of water overflow to 12.

The laws misinterpret or ignore the basic understanding of wetlands.

Legislators need to know that an “isolated wetland” does not exist.

Water travels within an area called a watershed.

The law needs to consider interconnections in water systems.

Wetlands naturally purify water.

Water filters and flows in wetlands.

Pavement and lawns carry water over, not through, the soil.

Who will save the wetlands if everyone is at the mall?

403

Federal laws should require implementing what we know.

The vital concept of interconnectedness means reeducating everyone from legislators to fourth graders.

Ecology must be incorporated into the curriculum for every grade.

Educating politicians, developers, and legislators is more difficult.

The choices people make in their schools, legislative systems, and daily lives will determine the future of water quality and flooding.

Learning by Doing Outlining

Learning by Doing Outlining

Outlining

Using one of your groups of ideas from the activities in Chapter 19, construct a formal topic outline that might serve as a guide for an essay.

Now turn that topic outline into a formal sentence outline.

Discuss both outlines with your classmates and instructor, bringing up any difficulties you met. If you get better notions for organizing, change the outline.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Planning

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Planning

Reflecting on Planning

Reflect on the purpose and audience for your current paper. Then return to thesis, outline, or other plans you have prepared. Will your plans accomplish your purpose? Are they directed to your intended audience? Make any needed adjustments. Exchange plans with a classmate or small group, and discuss ways to continue improving them.