Aziz Ansari, “Searching for Your Soul Mate”

Instructor's Notes

To assign the questions that follow this reading, click “Browse More Resources for this Unit,” or go to the Resources panel.To individually assign the Suggestions for Writing that follow this reading, click “Browse More Resources for this Unit,” or go to the Resources panel.

Aziz Ansari

Searching for Your Soul Mate

Aziz Ansari, an American actor and comedian, was born February 23, 1983, in Columbia, South Carolina. After graduating from New York University with a business degree, he decided to pursue his interests in acting and stand-up comedy. He has appeared on stage and on television, most notably as Tom Haverford on NBC’s Emmy-nominated comedy Parks and Recreation. In 2015, he gained accolades as a writer after Penguin Press published his book Modern Romance, which soon became a bestseller. A funny yet thoughtful look at the complexities of modern romance, the following excerpt from the first chapter explores the shift in attitudes toward marriage over the last half century.

AS YOU READ: What are men and women looking for today in a spouse? How do they decide when to marry?

495

1

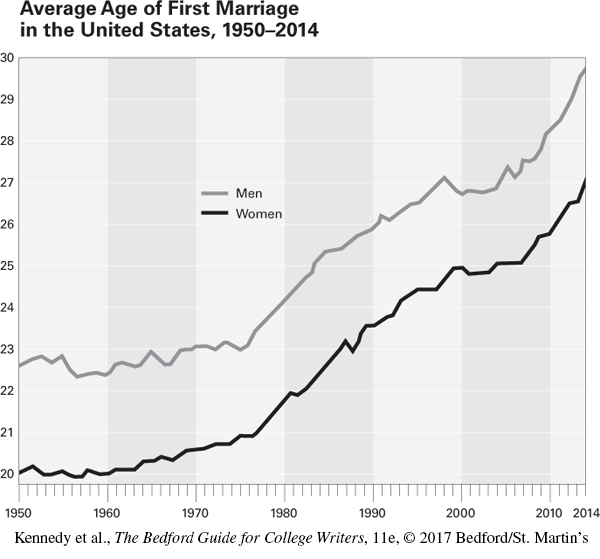

Today the average age of first marriage is about twenty-seven for women and twenty-nine for men, and it’s around thirty for both men and women in big cities like New York and Philadelphia.

2

Why has this age of first marriage increased so dramatically in the past few decades? For the young people who got married in the 1950s, getting married was the first step in adulthood. After high school or college, you got married and you left the house. For today’s folks, marriage is usually one of the later stages in adulthood. Now most young people spend their twenties and thirties in another stage of life, where they go to university, start a career, and experience being an adult outside of their parents’ home before marriage.

3

This period isn’t all about finding a mate and getting married. You have other priorities as well: getting educated, trying out different jobs, having a few relationships, and, with luck, becoming a more fully developed person. Sociologists even have a name for this new stage of life: emerging adulthood.

4

During this stage we also wind up greatly expanding our pool of romantic options. Instead of staying in the neighborhood or our building, we move to new cities, spend years meeting people in college and workplaces, and—in the biggest game changer—have the infinite possibilities provided by online dating and other similar technologies.

5

Besides the effects it has on marriage, emerging adulthood also offers young people an exciting, fun period of independence from their parents when they get to enjoy the pleasures of adulthood—before becoming husbands and wives and starting a family.

6

If you’re like me, you couldn’t imagine getting married without going through all this. When I was twenty-three, I knew nothing about what I was going to be as an adult. I was a business and biology major at NYU. Would I have married some girl who lived a few blocks from me in Bennettsville, South Carolina, where I grew up? What was this mysterious “biology business” I planned on setting up, anyway? I have no clue. I was an idiot who definitely wasn’t ready for such huge life decisions. . . .1

7

Before the 1960s, in most parts of the United States, single women simply didn’t live alone, and many families frowned upon their daughters moving into shared housing for “working girls.” Until they got married, these women were pretty much stuck at home under fairly strict adult supervision and lacked basic adult autonomy.° They always had to let their parents know their whereabouts and plans. Even dating had heavy parental involvement: The parents would either have to approve the boy or accompany them on the date.

8

At one point during a focus group with older women, I asked them straight out whether a lot of women their age got married just to get out of the house. Every single woman there nodded. For women in this era, it seemed that marriage was the easiest way of acquiring the basic freedoms of adulthood.

9

Things weren’t a breeze after that, though. Marriage, most women quickly discovered, liberated them from their parents but made them dependent on a man who might or might not treat them well and then saddled them with the responsibilities of homemaking and child rearing. It gave women of this era what was described at the time by Betty Friedan in her bestselling book The Feminine Mystique as “the problem that has no name.”2

496

10

Once women gained access to the labor market and won the right to divorce, the divorce rate skyrocketed. Some of the older women I met in our focus groups had left their husbands during the height of the divorce revolution, and they told me that they’d always resented missing out on something singular and special: the experience of being a young, unencumbered, single woman.

11

They wanted emerging adulthood.

12

The shift in when we look for love and marriage has been accompanied by a change in what we look for in a marriage partner. When the older folks I interviewed described the reasons that they dated, got engaged to, and then married their eventual spouses, they’d say things like “He seemed like a pretty good guy,” “She was a nice girl,” “He had a good job,” and “She had access to doughnuts and I like doughnuts.”

497

13

When you ask people today why they married someone, the answers are much more dramatic and loving. You hear things along the lines of “She is my other half,” “I can’t imagine experiencing the joys of life without him by my side,” or “Every time I touch her hair, I get a huge boner.”

14

On our subreddit we asked people: If you’ve been married or in a long-term relationship, how did you decide that the person was (or still is) the right person for you? What made this person different from others? The responses were strikingly unlike the ones we got from the older people we met at the senior center.

15

Many were filled with stories that illustrated a very deep connection between the two people that made them feel like they’d found someone unique, not just someone who was pleasant to start a family with. . . .

16

From the way they described things, it seemed like their bar for committing to someone was much higher than it had been for the older folks who settled down just a few generations ago.

17

To figure out why people today use such exalted° terms when they explain why they committed to their romantic partner, I spoke with Andrew Cherlin, the eminent° sociologist of the family and author of the book The Marriage-Go-Round. Up until about fifty years ago, Cherlin said, most people were satisfied with what he calls a “companionate marriage.” In this type of marriage each partner had clearly defined roles. A man was the head of his household and the chief breadwinner, while a woman stayed home, took care of the house, and had kids. Most of the satisfaction you gained in the marriage depended on how well you fulfilled this assigned role. As a man, if you brought home the bacon, you could feel like you were a good husband. As a woman, if you kept a clean house and popped out 2.5 kids, you were a good wife. You loved your spouse, maybe, but not in an “every time I see his mustache, my heart flutters like a butterfly” type of way.

18

You didn’t marry each other because you were madly in love; you married because you could make a family together. While some people said they were getting married for love, the pressure to get married and start a family was such that not every match could be a love match, so instead we had the “good enough marriage.”

19

Waiting for true love was a luxury that many, especially women, could not afford. In the early 1960s, a full 76 percent of women admitted they would be willing to marry someone they didn’t love. However, only 35 percent of the men said they would do the same.

20

If you were a woman, you had far less time to find a man. True love? This guy has a job and a decent mustache. Lock it down, girl.

21

This gets into a fundamental change in how marriage is viewed. Today we see getting married as finding a life partner. Someone we love. But this whole idea of marrying for happiness and love is relatively new.

22

498

For most of the history of our species, courtship and marriage weren’t really about two individuals finding love and fulfillment. According to the historian Stephanie Coontz, author of Marriage, a History, until recently a marital union was primarily important for establishing a bond between two families. It was about achieving security—financial, social, and personal. It was about creating conditions that made it possible to survive and reproduce.

23

This is not ancient history. Until the Industrial Revolution, most Americans and Europeans lived on farms, and everybody in the household needed to work. Considerations about whom to marry were primarily practical.

24

In the past, a guy would be thinking, Oh, shit, I gotta have kids to work on my farm. I need four-year-old kids performing manual labor ASAP. And I need a woman who can make me clothes. I better get on this. A woman would think, I better find a dude who’s capable on the farm, and good with a plow so I don’t starve and die.

25

Making sure the person shared your interest in sushi and Wes Anderson movies and made you get a boner anytime you touched her hair would seem far too picky.

26

Of course, people did get married because they loved each other, but their expectations about what love would bring were different from those we hold today. For families whose future security depended on their children making good matches, passion was seen as an extremely risky motivation for getting hitched.“Marriage was too vital an economic and political institution to be entered into solely on the basis of something as irrational as love,” writes Coontz.

27

Coontz also told us that before the 1960s most middle-class people had pretty rigid, gender-based expectations about what each person would bring to a marriage. Women wanted financial security. Men wanted virginity and weren’t concerned with deeper qualities like education or intelligence.

28

“The average couple wed after just six months—a pretty good sign that love was still filtered through strong gender stereotypes rather than being based on deep knowledge of the other partner as an individual,” she said.

29

Not that people who got married before the 1960s had loveless marriages. On the contrary, back then couples often developed increasingly intense feelings for each other as they spent time together, growing up and building their families. These marriages may have started with a simmer, but over time they could build to a boil.

30

But a lot of things changed in the 1960s and 1970s, including our expectations of what we should get out of a marriage. The push for women’s equality was a big driver of the transformation. As more women went to college, got good jobs, and achieved economic independence, they established newfound control over their bodies and their lives. A growing number of women refused to marry the guy in their neighborhood or building. They wanted to experience things too, and they now had the freedom to do it.

31

According to Cherlin, the generation that came of age during the sixties and seventies rejected companionate marriage and began to pursue something greater. They didn’t merely want a spouse—they wanted a soul mate.

32

By the 1980s, 86 percent of American men and 91 percent of American women said they would not marry someone without the presence of romantic love.

33

499

The soul mate marriage is very different from the companionate marriage. It’s not about finding someone decent to start a family with. It’s about finding the perfect person whom you truly, deeply love. Someone you want to share the rest of your life with. Someone with whom, when you smell a certain T-shirt they own, you are instantly whisked away to a happy memory about the time he or she made you breakfast and you both stayed in and binge-watched all eight seasons of Perfect Strangers.

34

We want something that’s very passionate, or boiling, from the get-go. In the past, people weren’t looking for something boiling; they just needed some water. Once they found it and committed to a life together, they did their best to heat things up. Now, if things aren’t boiling, committing to marriage seems premature.

35

But searching for a soul mate takes a long time and requires enormous emotional investment. The problem is that this search for the perfect person can generate a lot of stress. Younger generations face immense pressure to find the “perfect person” that simply didn’t exist in the past when “good enough” was good enough.

36

When they’re successful, though, the payoff is incredible. According to Cherlin, the soul mate marriage has the highest potential for happiness, and it delivers levels of fulfillment that the generation of older people I interviewed rarely reached.

37

Cherlin is also well aware of how hard it is to sustain all these good things, and he claims that today’s soul mate marriage model has the highest potential for disappointment. Since our expectations are so high, today people are quick to break things off when their relationship doesn’t meet them (touch the hair, no boner). Cherlin would also like me to reiterate that this hair/boner analogy is mine and mine alone.

38

The psychotherapist Esther Perel has counseled hundreds of couples who are having trouble in their marriages, and as she sees things, asking all of this from a marriage puts a lot of pressure on relationships. In her words:

Marriage was an economic institution in which you were given a partnership for life in terms of children and social status and succession and companionship. But now we want our partner to still give us all these things, but in addition I want you to be my best friend and my trusted confidant and my passionate lover to boot, and we live twice as long. So we come to one person, and we basically are asking them to give us what once an entire village used to provide: Give me belonging, give me identity, give me continuity, but give me transcendence° and mystery and awe all in one. Give me comfort, give me edge. Give me novelty, give me familiarity. Give me predictability, give me surprise. And we think it’s a given, and toys and lingerie are going to save us with that.

39

Ideally, though, we’re lucky, and we find our soul mate and enjoy that life-changing motherlode of happiness.

40

But a soul mate is a very hard thing to find.

500

Questions to Start You Thinking

Considering Meaning: Why do men wait longer to get married today than they did in the 1950s and 1960s? Women? How do their reasons for waiting reflect cultural changes?

Identifying Writing Strategies: How does Ansari use humor in his essay? What effect does it have on his main points? How does his humor help engage the reader? Refer to specific passages of text in your response.

Reading Critically: What do you think Betty Friedan meant by her determination that women in the early sixties experienced “the problem that has no name”? How did social expectations contribute to this “problem”?

Expanding Vocabulary: How do sociologists define the term emerging adulthood? What other experiences would you include in this category? Why are these experiences important during the maturation process?

Making Connections: In the last section of his article, Ansari looks at how modern men and women define a soul mate as the perfect person to marry. After reading “I Want a Wife,” do you think that Brady’s narrator would be able to find a soul mate today? Do you believe Ansari would argue that male and female roles have changed to the point where Brady’s narrator would be able to find a man who could accomplish all that was expected of a wife in 1971?

Link to the Paired Essay

In “The Marriage Imperative,” Michael Cobb argues that “some of us can’t or won’t ever find that special someone.” Why not? What qualities that men and women are looking for today in an ideal mate, as outlined by Ansari, would he find unrealistic and thus unattainable?

Journal Prompt

Ansari writes that in the past, couples entered into marriage for practical reasons, including the desire to have a family and to enjoy economic stability. Do you think that these needs, along with the yearning for a soul mate, motivate couples to marry today? What expectations do you believe are placed on partners in a modern marriage? How difficult do you think it is to live up to those expectations? What situations could arise that could undermine those expectations?

Suggestions for Writing

Interview a couple who got married before the 1960s and one who recently got married, asking them the following questions: How old were they when they got married? How long had they known each other when they got married? Why did they get married? How do their answers compare with the ones Ansari cites in “Searching for Your Soul Mate”?

Write an essay explaining how changes in male and female roles have affected when and why people marry.