Finding Sources in the Field

The goal of field research is the same as that of library and Internet research–to gather the information you need to answer your research question and then to marshal persuasive evidence to support your conclusions. When you interview, observe, or ask questions of people, you generate your own firsthand (or primary) evidence. Before you begin, find out from your instructor whether you need institutional approval for research involving other people (“human subjects approval”) from your school’s institutional review board (IRB).

630

For more on interviewing, see Ch. 6.

Interviewing

Interviews–conversations with a purpose–may be your main source of field material. Whenever possible, interview an expert in the field or, if you are researching a group, someone representative or typical. Prepare carefully.

TIPS FOR INTERVIEWING

Be sure your prospect is willing to be quoted in writing.

Make an appointment for a day when the person will have enough time–an hour if possible–for a thorough talk with you.

Arrive promptly, with carefully thought-out questions to ask.

Come ready to take notes, including key points, quotations, and descriptive details. If you also want to record, ask permission.

Really listen. Let the person open up.

Be flexible; allow the interview to move in unanticipated directions.

If a question draws no response, don’t persist; go on to the next one.

At the end of the interview, thank the interviewee, and arrange for an opportunity to clarify comments and confirm direct quotations.

Make additional notes right after the interview to preserve anything you didn’t have time to record during the interview.

If you can’t talk in person, try a telephone or online interview. Make an appointment for a convenient time, write out questions before you call, and take notes. Federal regulations, by the way, forbid recording a phone interview without notifying the person talking that you are doing so. Always be sure to notify your subject if you are recording them on Skype or another video chat service, too.

Learning by Doing Interviewing an Instructor

Learning by Doing Interviewing an Instructor

Interviewing an Instructor

Interview one of your instructors about his or her current research or field of study. Ask what the particular field requires by way of study or success. Ask if he or she would share tips for students who want to go into that field. Reflect on what it takes for an instructor to be successful and how you might apply this information to your own studies.

Observing

For more on observing, see Ch. 5.

An observation may provide you with essential information about a setting such as a workplace or a school. Some organizations will insist on your displaying valid identification; in advance, ask your instructor for a statement written on college letterhead declaring that you are a student doing field research. Make an appointment with the organization or individual and, on arrival, identify yourself and your purpose. Before you depart, be sure to thank the necessary parties for arranging the observation.

631

TIPS FOR OBSERVING

Establish a clear purpose–decide exactly what you want to observe and why.

Take notes so that you don’t skip important details in your paper.

Record facts, telling details, and sensory impressions. Notice the features of the place, the actions or relationships of the people there, or whatever relates to the purpose of your observation.

Consider taking photos or recording video if doing so doesn’t distract you from the scene. Photographs can illustrate your paper and help you recall and interpret details while you write. If you are in a private place, get written permission from the owner (or other authority) and any people you photograph.

Pause, look around, fill in missing details, and check the accuracy of your notes before you leave the observation site.

Thank the person who arranged your observation so you will be welcome again if you need to return to fill in gaps in your data or test new ideas.

Using Questionnaires

Questionnaires, or surveys, gather the responses of a number of people to a fixed set of questions. Online services such as SurveyMonkey allow you to quickly develop and deploy questionnaires for free. Professional researchers carefully design sets of questions and then randomly select representative people to respond in order to reach reliable answers. Because your survey will not be that extensive, avoid generalizing about your findings. It’s one thing to say that “many students” who filled out a questionnaire hadn’t read a newspaper in the past month; it’s another to claim that this is true of 72 percent of the students at your school–especially when your questionnaires went only to students in a specific major, and only half of them responded to the e-mail invitation.

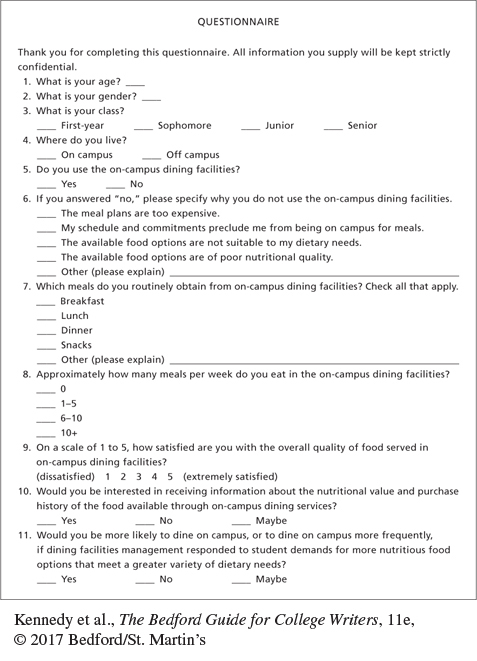

A more reliable way to treat questionnaires is as group interviews: assume that you collect typical views, use them to build your overall knowledge, and cull responses for compelling details or quotations. Use a questionnaire to concentrate on what a group thinks as a whole or when an interview to cover all your questions is impractical. (See Figure 31.7 for a sample questionnaire.)

TIPS FOR USING A QUESTIONNAIRE

Ask yourself what you want to discover with your questionnaire. Then thoughtfully invent questions to fulfill that purpose.

State questions clearly, and supply simple directions for easy responses. Test your questionnaire on classmates or friends before distributing it to the group you want to study.

Ask questions that call for checking options, marking yes or no, circling a number on a five-point scale, or writing a few words so responses are easy to tally. Try to ask for one piece of information per question.

632

If you wish to consider differences based on age, gender, or other variables, include some demographic questions.

Write unbiased questions to elicit factual responses. Don’t ask How religious are you? Instead ask What is your religious affiliation? and How often do you attend religious services? Then you could report actual numbers and draw logical inferences about respondents.

When appropriate, ask open-ended questions that call for short written responses. Although qualitative responses are more difficult to tally than quantitative ones, the answers may supply worthwhile quotations or suggest important issues or factors.

Try to distribute questionnaires at a set location or event, and collect them as they are completed. If necessary, have them returned to your campus mailbox or another secure location. The more immediate and convenient the return, the higher your return rate is likely to be. If you’re conducting the questionnaire online, try to send it out at a time when you know students won’t be too busy to respond (such as finals week), and consider sending a reminder as the deadline approaches.

Use a blank questionnaire or make an answer grid to mark and add up the answers for each question. Total the responses so you can report that a certain percentage selected a specific answer. Many online services will perform this work for you.

For fill-in or short answers, type up each answer or paste the answers into a new document. (Code each questionnaire with a number in case you want to trace an answer back to its origin.) Try rearranging the answers in the file, looking for logical groupings, categories, or patterns that accurately reflect the responses and enrich your analysis.

Corresponding

For advice on writing e-mail messages, see E-mail in Ch. 17. For advice on writing business letters, see Business Letters in Ch. 17.

Does your interview subject live too far away for you to speak to him or her in person? Search online for contact information. If you can’t easily locate an e-mail address or phone number, try to locate the individual on social media to introduce yourself, specify your query, and request further information. Do you need information from a group, such as the American Red Cross, or an elected official? The organization’s Web site should provide an e-mail address for your request, a physical mailing address, an FAQ page (that answers frequently asked questions), or files of brochures.

TIPS FOR CORRESPONDING

Plan ahead, and allow plenty of time for responses to your requests.

Make your message short and polite. Identify yourself, and explain your request. List any questions. Thank your correspondent.

Enclose a stamped, self-addressed envelope with the letter. Include your e-mail address in your message.

633

634

Attending Public and Online Events

College organizations bring interesting speakers to campus. Check your campus Facebook page, newspaper, and bulletin boards. In addition, professionals and special-interest groups convene for regional or national conferences. A lecture or conference can be a source of fresh ideas and an excellent introduction to the language of a discipline.

TIPS FOR ATTENDING EVENTS

Take notes on lectures, usually given by experts in the field who supply firsthand opinions or research findings.

Ask questions from the audience or talk informally with a speaker later.

Record who attended the event, as well as audience reactions and other background details that may be useful in writing your paper.

Depending on the gathering, a speaker might distribute his or her paper or presentation slides or post a copy online. Conferences often publish their proceedings–usually a set of the lectures delivered–but online publication takes months. Try the library Web site for past proceedings.

If you join an online discussion, you can observe, ask a question, or save or print the transcript for your records.

Reconsidering Your Field Sources

Each type of field research can raise particular questions. For example, when you observe an event or a setting, are people aware of being observed? If so, have they changed their behavior? Is your random sampling of people truly representative? Have you questioned everyone in a group thoroughly enough?

In addition, consider the credibility and consistency of your field sources. Did your source seem biased or prejudiced? If so, will you need to discount some of the source’s information? Did your source provide evidence to support or corroborate claims? Have you compared different people’s opinions, accounts, or evidence? Is any evidence hearsay–one person telling you the thoughts of another or recounting actions that he or she hasn’t witnessed? If so, can you check the information with another source or a different type of evidence? Did your source seem to respond consistently, seriously, and honestly? Has time possibly distorted memories of past events? Adjust your conclusions based on your field research in accord with your answers to such questions.