14 | Shifts

14|Shifts

789

Just as you can change position to view a scene from different vantage points, in your writing you can change the time or perspective. However, shifting tense or point of view unconsciously or unnecessarily within a passage creates ambiguity and confusion for readers.

14aMaintain consistency in verb tense.

A verb’s tense refers to the time when the action of a verb did, does, might, or will occur (see 8).

In a passage or an essay, use the same verb tense unless the time changes.

14bIf the time changes, change the verb tense.

To write about events in the past, use past tense verbs. To write about events in the present, use present tense verbs. If the time shifts, change tense.

I do not like the new television programs this year. The comedies are too realistic to be amusing, the adventure shows don’t have much action, and the law enforcement dramas drag on and on. Last year the programs were different. The sitcoms were hilarious, the adventure shows were action packed, and the dramas were fast paced. I prefer last year’s reruns to this year’s shows.

The time and the verb tense change appropriately from present (do like, are, don’t have, drag) to past (were, were, were, were) back to present (prefer), contrasting this year’s present with last year’s past programming.

NOTE: When writing about literature, the accepted practice is to use present tense verbs to summarize what happens in a story, poem, or play. When discussing other aspects of a work, use present tense for present time, past tense for past, and future tense for future.

Steinbeck wrote “The Chrysanthemums” in 1937. [Past tense for past time]

In “The Chrysanthemums,” Steinbeck describes the Salinas Valley as “a closed pot” cut off from the world by fog. [Present tense for story summary]

14cMaintain consistency in the voice of verbs.

For more on using active and passive voice, see 21.

Shifting unnecessarily from active to passive voice may confuse readers.

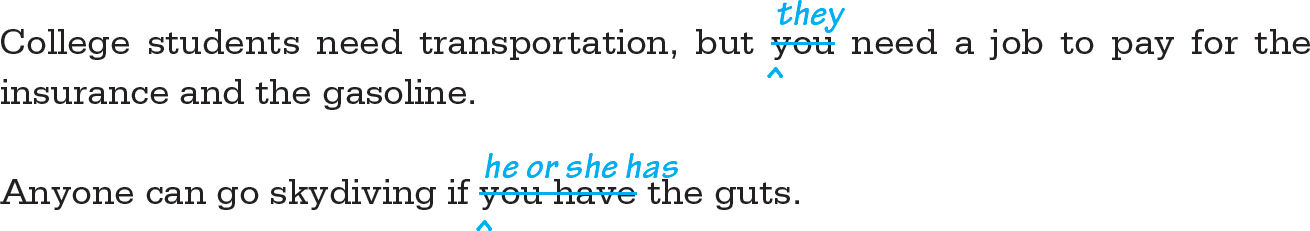

14dMaintain consistency in person.

For more on pronoun forms, see 1b and 10.

Person indicates your perspective as a writer. First person (I, we) establishes a personal, informal relationship with readers as does second person (you), which brings readers into the writing. Third person (he, she, it, they) is more formal and objective. In a formal scientific report, second person is seldom appropriate, and first, if used, might be reserved for reporting procedures. In a personal essay, using he, she, or one to refer to yourself would sound stilted. Choose the person appropriate for your purpose, and stick to it.

790

14eMaintain consistency in the mood of verbs.

For examples of the three moods of verbs, see 8j.

Avoid shifts in mood, usually from indicative to imperative.

14fMaintain consistency in level of language.

To impress readers, writers sometimes inflate their language or slip into slang. The level of language should fit your purpose and audience throughout an essay. For a personal essay, use informal language.

| INCONSISTENT | I felt like a typical tourist. I carried an expensive digital camera with lots of icons I didn’t quite know how to decode. But I was in a quandary because there was such a plethora of picturesque tableaus to record for posterity. |

Instead of suddenly shifting to formal language, the writer could end simply: But with so much beautiful scenery all around, I couldn’t decide where to start.

For an academic essay, use formal language.

| INCONSISTENT | Puccini’s Turandot is set in a China of legends, riddles, and fantasy. Brimming with beautiful melodies, this opera is music drama at its most spectacular. It rules! |

Cutting the last sentence avoids an unnecessary shift in formality.

EXERCISE 14-1 Maintaining Grammatical Consistency

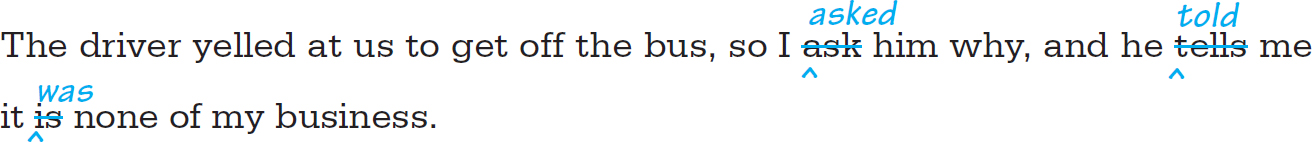

Revise the following sentences to eliminate shifts in verb tense, voice, mood, person, and level of language. Example:

791

Dr. Jamison is an erudite professor who cracks jokes in class.

The audience listened intently to the lecture, but the message was not understood.

Scientists can no longer evade the social, political, and ethical consequences of what they did in the laboratory.

To have good government, citizens must become informed on the issues. Also, be sure to vote.

Good writing is essential to success in many professions, especially in business, where ideas must be communicated in down-to-earth lingo.

Our legal system made it extremely difficult to prove a bribe. If the charges are not proven to the satisfaction of a jury or a judge, then we jump to the conclusion that the absence of a conviction demonstrates the innocence of the subject.

Before Morris K. Udall, Democrat from Arizona, resigns his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, he helped preserve hundreds of acres of wilderness.

Anyone can learn another language if you have the time and the patience.

The immigration officer asked how long we planned to stay, so I show him my letter of acceptance from Tulane.

Archaeologists spent many months studying the site of the African city of Zimbabwe, and many artifacts were uncovered.

Learning by Doing Considering Your Rough Draft

Learning by Doing Considering Your Rough Draft

Considering Your Rough Draft

One method of finding weak spots in an essay is to read it backward, sentence by sentence. This takes the essay out of the “normal” reading realm, where the brain is prone to insert assumed information that does not exist, and allows you to take each sentence on its own merit. This method also allows reviewers to better identify sentence fragments and run-on sentences, as well as missing words. Try this method to see what weak spots you find in your own essay. Write a reflection about what you discover.