Learning by Writing

The Assignment: Recalling a Personal Experience

Write about an experience that changed how you acted, thought, or felt. Use your experience as a springboard for reflection. Your purpose is not merely to tell an interesting story but to show your readers—your instructor and your classmates—the importance of that experience for you.

We suggest you pick an event that is not too personal, too subjective, or too big to convey effectively to others. Something that happened to you or that you observed, an encounter with a person who greatly influenced you, a decision that you made, or a challenge that you faced will be easier to recall (and to make vivid for your readers) than an interior experience like a religious conversion or falling in love.

These students recalled experiences heavy and light:

One writer recalled guitar lessons with a teacher who at first seemed harsh but who turned out to be a true friend.

Another student recalled a childhood trip when everything went wrong and she discovered the complexities of change.

Another recalled competing with a classmate who taught him a deeper understanding of success.

Facing the Challenge Writing from Recall

The major challenge writers confront when writing from recall is to focus their essays on a main idea. When writing about a familiar—and often powerful—experience, it is tempting to include every detail that comes to mind and equally easy to overlook familiar details that would make the story’s relevance clearer to the reader.

When you are certain of your purpose in writing about a particular event—what you want to show readers about your experience—you can transform a laundry list of details into a narrative that connects events clearly around a main idea. To help you decide what to show your readers, respond to each of these questions in a few sentences:

55

What was important to you about the experience?

What did you learn from it?

How did it change you?

How would you reply to a reader who asked “So what?”

Once you have decided on your main point about the experience, you should select the details that best illustrate that point and show readers why the experience was important to you.

Generating Ideas

For more on each strategy for generating ideas in this section or for additional strategies, see Ch. 19.

You may find that the minute you are asked to write about a significant experience, the very incident will flash to mind. Most writers, though, will need a little time for their memories to surface. Often, when you are busy doing something else—observing the scene around you, talking with someone, reading about someone else’s experience—the activity can trigger a recollection. When a promising one emerges, write it down. Perhaps, like Russell Baker, you found success when you ignored what you thought you were supposed to do in favor of what you really wanted to do. Perhaps, like Robert Schreiner, you learned from a painful experience.

Try Brainstorming. When you brainstorm, you just jot down as many ideas as you can. You can start with a suggestive idea—disobedience, painful lesson, childhood, peer pressure—and list whatever occurs through free association. You can also use the questions in the following checklist:

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

Did you ever break an important rule or rebel against authority? What did you learn from your actions?

Did you ever succumb to peer pressure? What were the results of going along with the crowd? What did you learn?

Did you ever regard a person in a certain way and then have to change your opinion of him or her? What produced this change?

Did you ever have to choose between two equally attractive alternatives? How might your life have been different if you had chosen differently?

Have you ever been appalled by witnessing an act of prejudice or insensitivity? What did you do? Do you wish you had done something different?

56

Try Freewriting. Devote ten minutes to freewriting—simply writing without stopping. If you get stuck, write “I have nothing to say” over and over, until ideas come. After you finish, you can circle or draw lines between related items, considering what main idea connects events.

Try Doodling or Sketching. As you recall an experience such as learning to drive, try sketching whatever helps you recollect the event and its significance. Turn doodles into words by adding comments on main events, notable details, and their impact on you.

Try Mapping Your Recollections. Identify a specific time period such as your birthday last year, the week when you decided to enroll in college, or a time when you changed in some way. On a blank page, on movable sticky notes, or in a digital file, record all the details you can recall about that time—people, statements, events, locations, and related physical descriptions.

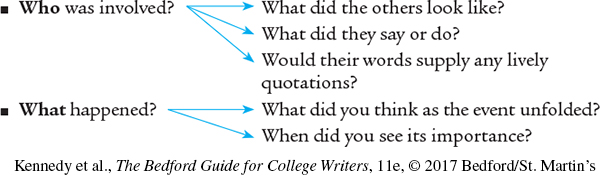

Try a Reporter’s Questions. Once you recall an experience you want to write about, ask “the five W’s and an H” that journalists find useful.

Who was involved?

What happened?

Where did it take place?

When did it happen?

Why did it happen?

How did the events unfold?

57

Any question might lead to further questions—and to further discovery.

Consider Sources of Support. Because your memory both retains and drops details, you may want to check your recollections of an experience. Did you keep a journal at the time? Do your memories match those of a friend or relative who was there? Was the experience (big game, new home, birth of a child) a turning point that you or your family would have photographed? Was it sufficiently public (such as a community catastrophe) or universal (such as a campus event) to have been in the news? If so, these resources can remind you of forgotten details or angles.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Writing Space

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Writing Space

Reflecting on Your Writing Space

Examine the place you go most frequently to write and study. Begin by creating a sketch or drawing of your writing space. Next, write a short description using details to create a vivid picture in the mind of your reader. Where is your writing space located? Is it a dedicated and private place, like a bedroom, or a shared space, like a study hall or the library? Do you sit at a desk? How are items in your writing space arranged? End your observations with a reflection on how you might improve your writing space to make it better suited to your writing. Can you identify problems with your current space? Is it too noisy? Too confined?

Planning, Drafting, and Developing

For more strategies for planning, drafting, and developing papers, see Chs. 20, 21, and 22.

Now, how will you tell your story? If the experience is still fresh in your mind, you may be able simply to write a draft, following the order of events. If you want to plan before you write, here are some suggestions.

For more on stating a thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20.

Start with a Main Idea, or Thesis. Jot down a few words that identify the experience and express its importance to you. Next, begin to shape these words into a sentence that states its significance—the main idea that you want to convey to a reader. If you aren’t certain yet about what that idea is, just begin writing. You can work on your thesis as you revise.

58

| TOPIC IDEA + SLANT | reunion in Georgia + really liked meeting family |

| WORKING THESIS | When I went to Georgia for a family reunion, I enjoyed meeting many relatives. |

Notice that Russell Baker describes a positive, life-changing experience, while Robert Schreiner focuses on a more disturbing recollection. To help identify the significance or slant of the experience you want to recall, you might state the most positive or troubling aspects of the experience and make a few notes about why you made these choices.

Learning by Doing Stating the Importance of Your Experience

Learning by Doing Stating the Importance of Your Experience

Stating the Importance of Your Experience

Work up to stating your thesis by completing these two sentences: The most important thing about my experience is _____________ . I want to share this so that my readers _____________. Exchange sentences with a classmate or a small group, either in person or online. Ask each other questions to sharpen ideas about the experience and express them in a working thesis.

For examples of time markers and other transitions, see Adding Cues and Connections in Ch. 21.

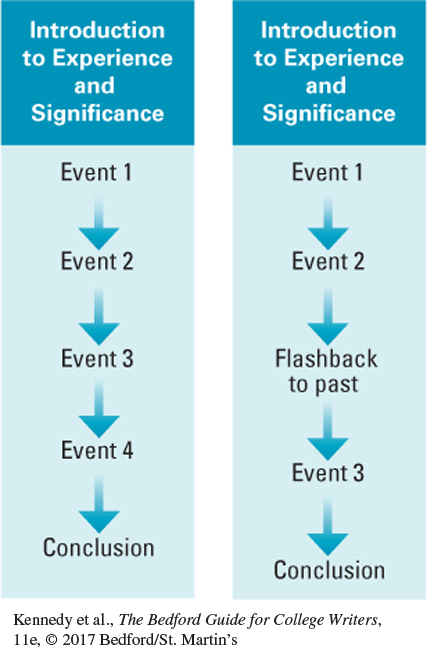

Establish Your Chronology. Retelling an experience is called narration, and the simplest way to organize is chronologically—relating the essential events in the order in which they occurred. On the other hand, sometimes you can start an account of an experience in the middle and then, through flashback, fill in whatever background a reader needs to know.

Richard Rodriguez, for instance, begins Hunger of Memory, a memoir of his bilingual childhood, with an arresting sentence:

I remember, to start with, that day in Sacramento, in a California now nearly thirty years past—when I first entered a classroom, able to understand about fifty stray English words.

The opening hooks our attention. In the rest of his essay, Rodriguez fills us in on his family history, on the gulf he came to perceive between the public language (English) and the language of his home (Spanish).

Learning by Doing Selecting and Arranging Events

Learning by Doing Selecting and Arranging Events

Selecting and Arranging Events

Recall the most important thing that happened to you this month, noting at least three related events in chronological order. Give each event of your story its own short paragraph with details to help your reader understand what happened, how it happened, and what the outcome was. Pay special attention to the order in which events occurred. Print your paragraphs. Now cut the paragraphs apart and arrange them so that, each time, your story starts and ends in a different place. Reflect on how the story changes when the order of events is changed.

For more on providing details, see Providing Details in Ch. 22.

59

Show Your Audience What Happened. How can you make your recollections come alive for your readers? Return to Baker’s account of Mr. Fleagle teaching Macbeth or Schreiner’s depiction of his cousin putting the wounded rabbits out of their misery. These writers have not merely told us what happened; they have shown us, by creating scenes that we can see in our mind’s eye.

For more on adding visuals, see section B in the Quick Format Guide.

As you tell your story, zoom in on at least two or three specific scenes. Show your readers exactly what happened, where it occurred, what was said, who said it. Use details and words that appeal to all five senses—sight, sound, touch, taste, smell. Carefully position any images you include to clarify visual details for readers. (Be sure that your instructor approves such additions.)

Revising and Editing

For more revising and editing strategies, see Ch. 23.

After you have written an early draft, put it aside for a few days—or hours if your deadline is looming. Then reread it carefully. Try to see it through the eyes of a reader, noting both pleasing and confusing spots. Revise to express your thoughts and feelings clearly and strongly to your readers.

Focus on a Main Idea, or Thesis. As you reread the essay, return to your purpose: What was so important about this experience? Why is it so memorable? Will readers see why it was crucial in your life? Will they understand how your life has been different ever since? Be sure to specify a genuine difference, reflecting the incident’s real impact on you.

| WORKING THESIS | When I went to Georgia for a family reunion, I enjoyed meeting many relatives. |

| REVISED THESIS | Meeting my Georgia relatives showed me how powerfully two values—generosity and resilience—unite my family. |

THESIS CHECKLIST

Does thesis clearly state why the experience was significant or memorable?

Does thesis (and the essay) focus on a single main idea, as opposed to various aspects of the experience?

Does it need to be refined in response to any new insights you’ve gathered while reflecting on, researching, or writing about the experience?

60

For general questions for a peer editor, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Peer Response Recalling an Experience

Peer Response Recalling an Experience

Recalling an Experience

Have a classmate or friend read your draft and suggest how you might present the main idea about your experience more clearly and vividly. Ask your peer editor questions such as these about writing from recall:

What do you think the writer’s main idea or thesis is? Where is it stated or clearly implied? Why was this experience significant?

What emotions do people in the essay feel? How did you feel as a reader?

Where does the essay come alive? Underline images, descriptions, and dialogue that seem especially vivid.

If this paper were yours, what is the one thing you would be sure to work on before handing it in?

Add Concrete Detail. Ask whether you have made events come alive for your audience by recalling them in sufficient concrete detail. Be specific enough that your readers can see, smell, taste, hear, and feel what you experienced. Make sure that all your details support your main idea or thesis. Notice again Robert Schreiner’s focus in his second paragraph on the world outside his own skin: his close recall of the snow, of his grandfather’s pointers about the habits of jackrabbits and the way to shoot them.

Learning by Doing Appealing to the Senses

Learning by Doing Appealing to the Senses

Appealing to the Senses

Working online or in person with a classmate, exchange short passages from your drafts. As you read each other’s paragraphs, highlight the sensory details—sights, sounds, tastes, sensations, and smells that bring a description to life. Then jot down the sense to which each detail appeals in the margin or in a file comment. Return each passage to the writer, review the notes about yours, and decide whether to strengthen your description with more—or more varied—details.

For more on outlining, see Organizing Your Ideas in Ch. 20.

For more on transitions, see Adding Cues and Connections in Ch. 21.

Follow a Clear Sequence. Reconsider the order of events, looking for changes that make your essay easier for readers to follow. For example, if a classmate seems puzzled about the sequence of your draft, make a rough outline or list of main events to check the clarity of your arrangement. Or add more transitions to connect events more clearly. Here are some useful questions about revising your paper:

REVISION CHECKLIST

Where have you shown why this experience was important and how it changed your life?

How have you engaged readers so they will keep reading? Will they see and feel your experience?

61

Why do you begin your narration as you do? Would another place in the draft make a better beginning?

If the events aren’t in chronological order, how have you made the organization easy for readers to follow?

In what ways does the ending provide a sense of finality?

Do you stick to a point? Is everything relevant to your main idea or thesis?

If you portray people, how have you made their importance clear? Which details make them seem real, not just shadowy figures?

Does the dialogue sound like real speech? Read it aloud. Try it on a friend.

For more on editing and proofreading strategies, see Editing and Proofreading in Ch. 23.

After you have revised your recall essay, edit and proofread it. Carefully check the grammar, word choice, punctuation, and mechanics—and then correct any problems you find. Here are some questions to get you started:

For more help, find the relevant checklist sections in the Quick Editing Guide and Quick Format Guide.

EDITING CHECKLIST

A1, A2Is your sentence structure correct? Have you avoided writing fragments, comma splices, or fused sentences?

A3Have you used correct verb tenses and forms throughout? When you present a sequence of past events, is it clear what happened first and what happened next?

C1When you use transitions and other introductory elements to connect events, have you placed any needed commas after them?

C3In your dialogue, have you placed commas and periods before (inside) the closing quotation mark?

D1, D2Have you spelled everything correctly, especially the names of people and places? Have you capitalized names correctly?

Also check your paper’s format using the Quick Format Guide. Follow the style expected by your instructor for features such as the heading, title, running head, page numbers, margins, and paragraph indentation.