Learning by Writing

The Assignment: Taking a Stand

152

Find a controversy that rouses your interest. It might be a current issue, a long-standing one, or a matter of personal concern: the pros and cons of legalizing medical marijuana, the contribution of sports to a school’s educational mission, or the need for menu changes at the cafeteria to accommodate ethnic, religious, and personal preferences. Your purpose isn’t to solve a social or moral problem but to make clear exactly where you stand on an issue and to persuade your readers to respect your position, perhaps even to accept it. As you reflect on your topic, you may change your position, but don’t shift positions in the middle of your essay.

Assume that your readers are people who may or may not be familiar with the controversy, so provide relevant background or an overview to help them understand the situation. They also may not have taken sides yet or may hold a position different from yours. You’ll need to consider their views and choose strategies to enlist their support.

Each of these students took a clear stand:

A writer who pays her own college costs disputed the opinion that working during the school year provides a student with valuable knowledge. Citing her painful experience, she maintained that devoting full time to studies is far better than juggling school and work.

Another writer challenged his history textbook’s portrayal of Joan of Arc as “an ignorant farm girl subject to religious hysteria.”

A member of the wrestling team argued that the number of weight categories in the sport should be increased because athletes who overtrain to qualify for the existing categories often damage their health.

Facing the Challenge Taking a Stand

The major challenge writers face when taking a stand is to gather enough relevant evidence to support their position. Without such evidence, you’ll convince only those who agreed with you in the first place. You also won’t persuade readers by ranting emotionally about an issue or insulting as ignorant those who hold different opinions. Moreover, few readers respect an evasive writer who avoids taking a stand.

153

What does work is respect—yours for the views of readers who will, in turn, respect your opinion, even if they don’t agree with it. You convey—and gain—respect when you anticipate readers’ objections or counterarguments, demonstrate knowledge of these alternate views, and present evidence that addresses others’ concerns as it strengthens your argument.

To anticipate and find evidence that acknowledges other views, list groups that might have strong opinions on your topic. Then try putting yourself in the shoes of a member of each group by writing a paragraph on the issue from that point of view.

What would that person’s opinion be?

On what grounds might he or she object to your argument?

How can you best address these concerns and overcome objections?

Your paragraph will suggest additional evidence to support your claims.

Generating Ideas

For more strategies for generating ideas, see Ch. 19.

For this assignment, you will need to select an issue, take a stand, develop a clear position, and assemble evidence that supports your view.

Find an Issue. The topic for this paper should be an issue or a controversy that interests both you and your audience. Try brainstorming a list of possible topics. Start with the headlines of a newspaper or newsmagazine, review the letters to the editor, check the political cartoons on the opinion page, or watch for stories on demonstrations or protests. You might also consult the library index to CQ Researcher, browse news or opinion Web sites, talk with friends, or consider topics raised in class. If you keep a journal, look over your entries to see what has perplexed or angered you. If you need to understand the issue better or aren’t sure you want to take a stand on it, investigate by freewriting, reading, or turning to other sources.

Once you have a list of possible topics, drop those that seem too broad or complex or that you don’t know much about. Weed out anything that might not hold your—or your readers’—interest. From your new list, pick the issue or controversy for which you can make the strongest argument.

Learning by Doing Finding a Workable Topic

Learning by Doing Finding a Workable Topic

Finding a Workable Topic

Make a list of possible topics for an argument essay. Then take a close look at the list, eliminating topics that are too broad, too specific, or not focused. For example, if you are limited to one thousand words, do you have enough space to write about the broad topic of hunger in Africa? You might exchange topic lists with other students and discuss which topics are most or least promising.

154

Start with a Question and a Thesis. At this stage, many writers try to pose the issue as a question—one that will be answered through the position they take. Skip vague questions that most readers wouldn’t debate, or convert them to questions that allow different stands.

| VAGUE QUESTION | Is stereotyping bad? |

| CLEARLY DEBATABLE | Should we fight gender stereotypes in advertising? |

You can help focus your position by stating it in a sentence—a thesis, or statement of your stand. Your statement can answer your question:

For more on stating a thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20.

| WORKING THESIS | We should expect advertisers to fight rather than reinforce gender stereotypes. |

| OR | Most people who object to gender stereotypes in advertising need to get a sense of humor. |

Your thesis should invite continued debate by taking a strong position that can be argued rather than stating a fact.

| FACT | Hispanics constitute 16 percent of the community but only 3 percent of our school population. |

| WORKING THESIS | Our school should increase outreach to the Hispanic community, which is underrepresented on campus. |

Notice that both Suzan Shown Harjo and Marjorie Lee Garretson pose questions in their introductory paragraphs that are then addressed in their thesis statements. If you came up with a debatable question to devise your thesis, you might revisit and revise this question later, to develop a strong introduction.

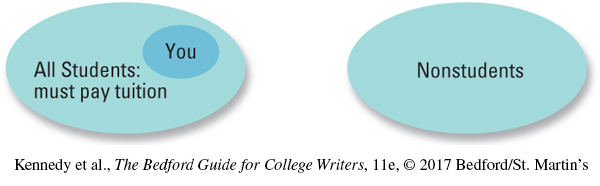

Use Formal Reasoning to Refine Your Position. As you take a stand on a debatable matter, you are likely to use reasoning as well as specific evidence to support your position. A syllogism is a series of statements, or premises, used in traditional formal logic to lead deductively to a logical conclusion.

| MAJOR STATEMENT | All students must pay tuition. |

| MINOR STATEMENT | You are a student. |

| CONCLUSION | Therefore, you must pay tuition. |

For a syllogism to be logical, ensuring that its conclusion always applies, its major and minor statements must be true, its definitions of terms must remain stable, and its classification of specific persons or items must be accurate. In real-life arguments, such tidiness may be hard to achieve.

155

For example, maybe we all agree with the major statement above that all students must pay tuition. However, some students’ tuition is paid for them through a loan or scholarship. Others are admitted under special programs, such as a free-tuition benefit for families of college employees or a back-to-college program for retirees. Further, the word student is general; it might apply to students at public high schools who pay no tuition. Next, everyone might agree that you are a student, but maybe you haven’t completed registration or the computer has mysteriously dropped you from the class list. Such complications can threaten the success of your conclusion, especially if your audience doesn’t accept it. In fact, many civic and social arguments revolve around questions such as these: What—exactly—is the category or group affected? Is its definition or consequence stable—or does it vary? Who falls in or out of the category?

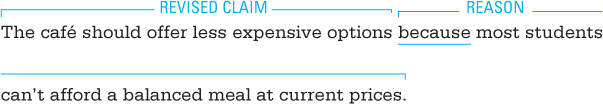

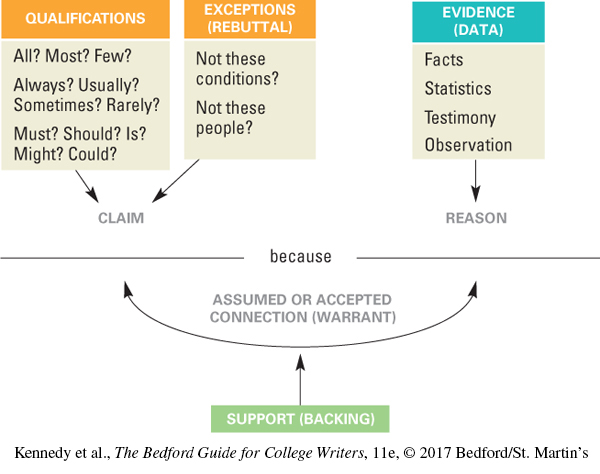

Use Informal Toulmin Reasoning to Refine Your Position. A contemporary approach to logic is presented by the philosopher Stephen Toulmin (1922–2009) in The Uses of Argument (2nd ed., 2003). He describes an informal way of arguing that acknowledges the power of assumptions in our day-to-day reasoning. This approach starts with a concise statement—the essence of an argument—that makes a claim and supplies a reason to support it.

Click here for accessible version of above content.

You develop a claim by supporting your reasons with evidence—your data or grounds. For example, your evidence might include facts about the cost of lunches on campus, especially in contrast to local fast-food options, and statistics about the limited resources of most students at your campus.

However, most practical arguments rely on a warrant, your thinking about the connection or relationship between your claim and your supporting data. Because you accept this connection and assume that it applies, you generally assume that others also take it for granted. For instance, nearly all students might accept your assumption that a campus café should serve the needs of its customers. Many might also agree that students should take action rather than allow a campus facility to take advantage of them by charging high prices. Even so, you could state your warrant directly if you thought that your readers would not see the connection that you do. You also could back up your warrant, if necessary, in various ways:

using facts, perhaps based on quality and cost comparisons with food service operations on other campuses

using logic, perhaps based on research findings about the relationship between cost and nutrition for institutional food as well as the importance of good nutrition for brain function and learning

making emotional appeals, perhaps based on happy memories of the café or irritation with its options

156

making ethical appeals, perhaps based on the college mission statement or other expressions of the school’s commitment to students

As you develop your reasoning, you might adjust your claim or your data to suit your audience, your issue, or your refined thinking. For instance, you might qualify your argument (perhaps limiting your objections to most, but not all, of the lunch prices). You might also add a rebuttal by identifying an exception to it (perhaps excluding the fortunate, but few, students without financial worries due to good jobs or family support). Or you might simply reconsider your claim, concluding that the campus café is, after all, convenient for students and that the manager might be willing to offer more inexpensive options without a student boycott.

Click here for accessible version of above content.

Toulmin reasoning is especially effective for making claims like these:

Fact—Loss of polar ice can accelerate ocean warming.

Cause—The software company went bankrupt because of its excessive borrowing and poor management.

Value—Cell phone plan A is a better deal than cell phone plan B.

Policy—Admissions policies at Triborough University should be less restrictive.

157

DISCOVERY CHECKLIST

What issue or controversy concerns you? What current debate engages you?

What position do you want to take? How can you state your stand? What evidence might you need to support it?

How might you refine your working thesis? How could you make statements more accurate, definitions clearer, or categories more exact?

What assumptions are you making? What clarification of or support for these assumptions might your audience need?

Select Evidence to Support Your Position. When you state your claim, you state your overall position. You also may state supporting claims as topic sentences that establish your supporting points, introduce supporting evidence, and help your reader follow your reasoning. To decide how to support a claim, try to reduce it to its core question. Then figure out what reliable and persuasive evidence might answer the question.

As you begin to look for supporting evidence, consider the issue in terms of the three general types of claims—claims that require substantiation, provide evaluation, and endorse policy.

Claims of Substantiation: What Happened?

These claims require examining and interpreting information in order to resolve disputes about facts, circumstances, causes or effects, definitions, or the extent of a problem.

Sample Claims:

Certain types of cigarette ads, such as the once-popular Joe Camel ads, significantly encouraged smoking among teenagers.

Although body cameras worn by police will not always prevent unnecessary use of force, they are showing promise in reducing police brutality.

On the whole, bilingual education programs actually help students learn English more quickly than total immersion programs do.

Possible Supporting Evidence:

Facts and information: parties involved, dates, times, places

Clear definitions of terms: police brutality or total immersion

Well-supported comparison and contrast: statistics or examples to contrast suggestions that footage from police cameras sometimes offers inconclusive information with evidence that the footage has significantly reduced the unnecessary use of force

Well-supported cause-and-effect analysis: authoritative information to demonstrate how actions of tobacco companies “significantly encouraged smoking” or bilingual programs “help students learn English faster”

Claims of Evaluation: What Is Right?

These claims consider right or wrong, appropriateness or inappropriateness, and worth or lack of worth involved in an issue.

158

Sample Claims:

Research using fetal tissue is unethical in a civilized society.

English-only legislation promotes cultural intolerance in our society.

Keeping children in foster care for years, instead of releasing them for adoption, is wrong.

Possible Supporting Evidence:

Explanations or definitions of appropriate criteria for judging: deciding what’s “unethical in a civilized society”

Corresponding details and reasons showing how the topic does or does not meet the criteria: details or applications of English-only legislation that meet the criteria for “cultural intolerance” or reasons with supporting details that show why years of foster care meet the criteria for being “wrong”

Claims of Policy: What Should Be Done?

These claims challenge or defend approaches for achieving generally accepted goals.

Sample Claims:

The federal government should support the distribution of clean needles to reduce the rate of HIV infection among intravenous drug users.

Denying children of undocumented workers enrollment in public schools will reduce the problem of illegal immigration.

All teenagers accused of murder should be tried as adults.

Possible Supporting Evidence:

Explanation and definition of the policy goal: assuming that most in your audience agree that it is desirable to reduce “the rate of HIV infection” or “the problem of illegal immigration” or to try murderers in the same way regardless of age

Corresponding details and reasons showing how your policy recommendation would meet the goal: results of “clean needle” trials or examples of crime statistics and cases involving teen murderers

Explanations or definitions of the policy’s limits or applications, if needed: why some teens should not be tried as adults because of their situations

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Evidence for Your Argument

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Evidence for Your Argument

Reflecting on Evidence for Your Argument

Reflect on the claim about which you are taking a stand. Think about whether this is a claim of substantiation, evaluation, or policy or some combination. What types of evidence do you think would be most effective for persuading your audience of your claim’s validity? Where and how might you find such evidence?

159

Consider Your Audience as You Develop Your Claim. The nature of your audience might influence the type of claim you choose to make. For example, suppose that the nurse or social worker at the high school you attended or that your children now attend proposed distributing free condoms to students. The following table illustrates how the responses of different audiences to this proposal might vary with the claim. As you develop your claims, try to put yourself in the place of your audience. For example, if you are a former student, what claim would most effectively persuade you? If you are the parent of a teenager, what claim would best address both your general views and your specific concerns about your own child?

| Audience | Type of Claim | Possible Effect on Audience |

| Conservative parents who believe that free condoms would promote immoral sexual behavior | Evaluation: In order to save lives and prevent unwanted pregnancies, distributing free condoms in high school is our moral duty. | Counterproductive if the parents feel that they are being accused of immorality for not agreeing with the proposal |

| Conservative parents who believe that free condoms would promote immoral sexual behavior | Substantiation: Distributing free condoms in high school can effectively reduce pregnancy rates and the spread of STDs, especially AIDS, without substantially increasing the rate of sexual activity among teenagers. | Possibly persuasive, based on effectiveness, if parents feel that their desire to protect their children from harm, no matter what, is recognized and the evidence deflates their main fear (promoting sexual activity) |

| School administrators who want to do what’s right but don’t want hordes of angry parents pounding down the school doors | Policy: Distributing free condoms in high school to prevent unwanted pregnancies and the spread of STDs, including AIDS, is best accomplished as part of a voluntary sex education program that strongly emphasizes abstinence as the primary preventative. | Possibly persuasive if administrators see that the proposal addresses health and pregnancy issues without setting off parental outrage (by proposing a voluntary program that would promote abstinence, thus addressing concerns of parents) |

For more about using sources, see Ch. 12 and the Quick Research Guide.

Assemble Supporting Evidence. Your claim stated, you’ll need evidence to support it. That evidence can be anything that demonstrates the soundness of your position and the points you make—facts, statistics, observations, expert testimony, illustrations, examples, and case studies.

The four most important sources of evidence are facts, statistics, expert testimony, and firsthand observation.

Facts. Facts are statements that can be verified objectively, by observation or by reading a reliable account. They are usually stated dispassionately: “If you pump the air out of a five-gallon varnish can, it will collapse.” Of course, we accept many of our facts based on the testimony of others. For example, we believe that the Great Wall of China exists, although we may never have seen it with our own eyes.

160

Sometimes people say facts are true statements, but truth and sound evidence may be confused. Consider the truth of these statements:

| The tree in my yard is an oak. | True because it can be verified |

| A kilometer is 1,000 meters. | True using the metric system |

| The speed limit on the highway is 65 miles per hour. | True according to law |

| Fewer fatal highway accidents have occurred since the new exit ramp was built. | True according to research studies |

| My favorite food is pizza. | True as an opinion |

| More violent criminals should receive the death penalty. | True as a belief |

| Murder is wrong. | True as a value judgment |

Some would claim that each statement is true, but when you think critically, you should avoid treating opinions, beliefs, judgments, or personal experience as true in the same sense that verifiable facts and events are true.

Statistics. Statistics are facts expressed in numbers. What portion of American children are poor? According to statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau, 16.1 million children (or 21.8 percent of all children) lived in poverty in 2012 compared with 14.7 million (or 19.9 percent) in 2013. Clear as such figures seem, they may raise complex questions. For example, how significant is this decrease in the poverty rate? Is it an aberration or part of a longer trend? What percentage of children were poor over longer terms such as fifteen years or twenty?

Most writers, without trying to be dishonest, interpret statistics to help their causes. The statement “Fifty percent of the populace have incomes above the poverty level” might substantiate the fine job done by the government of a developing nation. Putting the statement another way—“Fifty percent of the populace have incomes below the poverty level”—might use the same statistic to show the inadequacy of the government’s efforts.

Even though a writer is free to interpret a statistic, statistics should not be used to mislead. On the wrapper of a peanut candy bar, we read that a one-ounce serving contains only 150 calories. The claim is true, but the bar weighs 1.6 ounces. Gobble it all—more likely than eating 62 percent of it—and you’ll ingest 240 calories, a heftier snack than the innocent statistic on the wrapper suggests. Because abuses make some readers automatically distrustful, use figures fairly when you write, and make sure they are accurate. If you doubt a statistic, compare it with figures reported by several other sources. Distrust a statistical report that differs from every other report unless it is backed by further evidence.

Should you want to contact a campus expert, see Ch. 6 for advice about interviews.

161

Expert Testimony. By “experts,” we mean people with knowledge gained from study and experience in a particular field. The test of an expert is whether his or her expertise stands up to the scrutiny of others who are knowledgeable in that field. The views of Peyton Manning on how to play offense in football carry authority. So do the views of economist and Federal Reserve chairwoman Janet Yellen on what causes inflation. However, Manning’s take on the economy or Yellen’s thoughts on football might not be authoritative. Also consider whether the expert has any bias or special interest that would affect reliability. Statistics on cases of lung cancer attributed to smoking might be better taken from government sources than from the tobacco industry.

For more on observation, see Ch. 5.

Firsthand Observation. Firsthand observation is persuasive. It can add concrete reality to abstract or complex points. You might support the claim “The Meadowfield waste recycling plant fails to meet state guidelines” by recalling your own observations: “When I visited the plant last January, I was struck by the number of open waste canisters and by the lack of protective gear for the workers who handle these toxic materials daily.”

For more on logical fallacies, see Learning by Writing.

As readers, most of us tend to trust the writer who declares, “I was there. This is what I saw.” Sometimes that trust is misplaced, however, so always be wary of a writer’s claim to have seen something that no other evidence supports. Ask yourself, Is this writer biased? Might the writer have (intentionally or unintentionally) misinterpreted what he or she saw? Of course, your readers will scrutinize your firsthand observations, too; take care to reassure them that your observations are unbiased and accurate. Evidence must be used carefully to avoid defending logical fallacies—common mistakes in thinking—and making statements that lead to wrong conclusions. Examples are easy to misuse (claiming proof by example or too few examples). Because two professors you know are dissatisfied with state-mandated testing programs, you can’t claim that all—or even most—professors are. Even if you surveyed more professors at your school, you could speak only generally of “many professors.” To claim more, you might need to conduct scientific surveys, access reliable statistics from the library or Internet, or solicit the views of a respected expert in the area.

Learning by Doing Supporting a Claim

Learning by Doing Supporting a Claim

Supporting a Claim

Write out, in one complete sentence, the core claim or position you plan to support. Working in a small group, drop all these “position statements” into a hat, with no names attached. Then draw and read each aloud in turn, inviting the group to suggest useful supporting evidence and possible sources for it. Ask someone in the group to act as a recorder, listing suggestions on a separate page for each claim. Finally, match up writers with claims, and share reactions. (If you are working online, follow your instructor’s directions, possibly sending your statement privately to your instructor for anonymous posting for a threaded discussion.) If this activity causes you to alter your stand, be thankful: it will be easier to revise now rather than later.

162

Record Evidence. For this assignment, you will need to record your evidence in written form in a notebook or a digital file. Note exactly where each piece of information comes from. Keep the form of your notes flexible so that you can easily rearrange them as you plan your draft.

For more on testing evidence, see section D of the Quick Research Guide.

Test and Select Evidence to Persuade Your Audience. Now that you’ve collected some evidence, sift through it to decide which information to use. Always critically test and question evidence to see whether it is strong enough to carry the weight of your claims.

EVIDENCE CHECKLIST

Is it accurate?

For advice on evaluating sources of evidence, see section C in the Quick Research Guide.

● Do the facts and figures seem accurate based on what you have found in published sources, reports by others, or reference works?

● Are figures or quoted facts copied correctly?

Is it reliable?

● Is the source trustworthy and well regarded?

● Does the source acknowledge any commercial, political, advocacy, or other bias that might affect the quality of its information?

● Does the writer supplying the evidence have appropriate credentials or experience? Is the writer respected as an expert in the field?

● Do other sources agree with the information?

Is it up-to-date?

● Are facts and statistics—such as population figures—current?

● Is the information from the latest sources?

Is it to the point?

● Does the evidence back the exact claim made?

● Is the evidence all pertinent? Does any of it drift from the point to interesting but irrelevant evidence?

Is it representative?

● Are examples typical of all the things included in the writer’s position?

● Are examples balanced? Do they present the topic or issue fairly?

● Are contrary examples acknowledged?

Is it appropriately complex?

● Is the evidence sufficient to account for the claim made?

● Does it avoid treating complex things superficially?

● Does it avoid needlessly complicating simple things?

163

Is it sufficient and strong enough to back the claim and persuade readers?

● Are the amount and quality of the evidence appropriate for the claim and for the readers?

● Is the evidence aligned with the existing knowledge of readers?

● Does the evidence answer the questions readers are likely to ask?

● Is the evidence vivid and significant?

Learning by Doing Examining Your Evidence

Learning by Doing Examining Your Evidence

Examining Your Evidence

Examine the evidence that you’ve gathered to support your thesis, and consider whether or not each piece of evidence directly backs up your thesis. If any evidence does not directly support your thesis, you may want to eliminate it.

You may find that your evidence supports a different stand than you intended to take. Might you find facts, testimony, and observations to support your original position after all? Or should you rethink your position? If so, revise your working thesis. Does your evidence cluster around several points or reasons? If so, use your evidence to plan the sequence of your essay.

In addition, consider whether information presented visually would strengthen your case or make your evidence easier for readers to grasp.

For more on the use of visuals and their placement, see section B in the Quick Format Guide.

Graphs can effectively show facts or figures.

Tables can convey terms or comparisons.

Photographs or other illustrations can substantiate situations.

Test each visual as you would test other evidence for accuracy, reliability, and relevance. Mention each visual in your text, and place the visual close to that reference. Cite the source of any visual you use and of any data you consolidate in your own graph or table.

Most effective arguments take opposing viewpoints into consideration whenever possible. Doing so demonstrates that the writer respects those viewpoints, thereby encouraging readers to respect the viewpoint the writer presents. Providing evidence that refutes opposing viewpoints can also bolster an argument’s strength. Use these questions to help you assess your evidence from this standpoint.

ANALYZE YOUR READERS’ POINTS OF VIEW

What are their attitudes? Interests? Priorities?

What do they already know about the issue?

What do they expect you to say?

Do you have enough appropriate evidence that they’ll find convincing?

FOCUS ON THOSE WITH DIFFERENT OR OPPOSING OPINIONS

164

What are their opinions or claims?

What is their evidence?

Who supports their positions?

Do you have enough appropriate evidence to show why their claims are weak, only partially true, misguided, or just plain wrong?

ACKNOWLEDGE AND REBUT THE COUNTERARGUMENTS

What are the strengths of other positions? What might you want to concede or grant to be accurate or relevant?

What are the limitations of other positions? What might you want to question or challenge?

What facts, statistics, testimony, observations, or other evidence supports questioning, qualifying, or challenging other views?

Learning by Doing Addressing Counterarguments

Learning by Doing Addressing Counterarguments

Addressing Counterarguments

State your position on a debatable issue (for example, “I think the Snake River dams in Idaho should be demolished”). Then add the word because to your statement and list two or three main reasons why you support this position. Think about what a reader would need to understand or consider in order to be persuaded that your position is correct. This will be the nucleus of your argument. Next, consider arguments that might be made in opposition to your views and questions that might be raised. Write some notes on how you would answer or refute these questions and counterarguments. Exchange papers with a partner to see if he or she has anything to contribute.

Planning, Drafting, and Developing

Reassess Your Position and Your Thesis. Now that you have looked into the issue, what is your current position? If necessary, revise thesis that you formulated earlier. Then summarize your reasons for holding this view, and list your supporting evidence.

| WORKING THESIS | We should expect advertisers to fight rather than reinforce gender stereotypes. |

| REFINED THESIS | Consumers should spend their shopping dollars thoughtfully in order to hold advertisers accountable for reinforcing rather than resisting gender stereotypes. |

165

THESIS CHECKLIST

Is it clearly debatable—something that you can take a position on? Is it more than just a factual statement?

Does it take a strong position?

Does it need to be refined or qualified in response to evidence that you’ve gathered or to any rethinking of your original position?

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Thesis

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Thesis

Reflecting on Your Thesis

Oftentimes, our research shapes our thesis statement, changing the way we once thought. Reflect on your own research to date and the evidence you have collected to support your position, including any counterarguments and possible refutations to those counterarguments. Has your reflection caused you to change your position or your thesis statement? If so, in what ways has your thesis changed? Consider how changes in your thesis statement might make your argument stronger.

For more on outlines, see Organizing Your Ideas in Ch. 20.

Organize Your Material to Persuade Your Audience. Arrange your notes into the order you think you’ll follow, perhaps making an outline. One useful pattern is the classical form of argument:

Introduce the subject to gain the readers’ interest.

State your main point or thesis.

If useful, supply historical background or an overview of the situation.

Present your points or reasons, and provide evidence to support them.

Refute the opposition.

Reaffirm your main point.

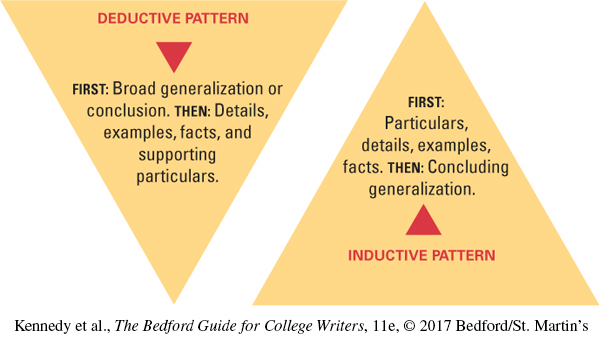

Note that most college papers are organized deductively—that is, they begin with a general statement (often a thesis) and then present particular cases to support or apply it. However, when you expect readers to be hostile to your position, stating your position too early might alienate resistant readers or make them defensive. Instead, you may want to refute the opposition first, then replace those views by building a logical chain of evidence that leads to your main point, and finally state your position. Papers that begin with particular details and evidence and then lead up to a larger generalization are organized inductively. Of course, you can always try both approaches to see which one works better. Note also that some papers will be mostly based on refutation (countering opposing views) and some mostly on confirmation (directly supporting your position). Others might even alternate refutation and confirmation rather than separate them.

166

Define Your Terms. To prevent misunderstanding, make clear any unfamiliar or questionable terms used in your thesis. If your position is “Humanists are dangerous,” you will want to give a short definition of what you mean by humanists and by dangerous early in the paper.

Attend to Logical, Emotional, and Ethical Appeals. The logical appeal engages readers’ intellect; the emotional appeal touches their hearts; the ethical appeal draws on their sense of fairness and reasonableness. A persuasive argument usually operates on all three levels. For example, you might use all three appeals to support a thesis about the need to curb accidental gunshot deaths, as the table on page 167 illustrates.

Learning by Doing Identifying Types of Appeals

Learning by Doing Identifying Types of Appeals

Identifying Types of Appeals

Bring to class or post links for the editorial or opinion page from a newspaper, newsmagazine, or blog with a strong point of view. Read some of the pieces, and identify the types of appeals used by each author to support his or her point. With classmates, evaluate the effectiveness of these appeals.

For pointers on integrating and documenting sources, see Ch. 12, as well as section D and section E in the Quick Research Guide.

Credit Your Sources. As you write, make your sources of evidence clear. One simple way to do so is to incorporate your source into the text: “As analyzed in an article in the May 25, 2015, issue of Time” or “According to my history professor, Dr. Harry Cleghorn . . .”

Revising and Editing

For more revising and editing strategies, see Ch. 23.

When you’re writing a paper that takes a stand, you may fall in love with the evidence you’ve gone to such trouble to collect. Taking out information is hard to do, but if it is irrelevant, redundant, or weak, the evidence won’t help your case. Play the crusty critic as you reread your paper. Consider outlining what it actually includes so that you can check for missing or unnecessary points or evidence. Pay special attention to the suggestions of friends or classmates who read your draft for you. Apply their advice by ruthlessly cutting unneeded material, as in the following passage:

The school boundary system requires children who are homeless or whose families move frequently to change schools repeatedly. They often lack clean clothes, winter coats, and required school supplies. As a result, these children struggle to establish strong relationships with teachers, to find caring advocates at school, and even to make friends to join for recess or lunch.

167

| Type of Appeal | Ways of Making the Appeal | Possible Supporting Evidence |

| Logical (logos) |

|

|

| Emotional (pathos) |

|

|

| Ethical (ethos) |

|

|

For general questions for a peer editor, see Re-viewing and Revising in Ch. 23.

Peer Response Taking a Stand

Peer Response Taking a Stand

Taking a Stand

168

Enlist several other students to read your draft critically and tell you whether they accept your arguments. For a paper in which you take a stand, ask your peer editors to answer questions such as these:

Can you state the writer’s claim?

Do you have any problems following or accepting the reasons for the writer’s position? Would you make any changes in the reasoning?

How persuasive is the writer’s evidence? What questions do you have about it? Can you suggest good evidence the writer has overlooked?

Has the writer provided enough transitions to guide you through the argument?

Has the writer made a strong case? Are you persuaded to his or her point of view? If not, is there any point or objection that the writer could address to make the argument more compelling?

If this paper were yours, what is the one thing you would be sure to work on before handing it in?

Use the Take Action chart to help you figure out how to improve your draft. Skim the left-hand column to identify questions you might ask about strengthening support for your stand. When you answer a question with “Yes” or “Maybe,” move straight across to Locate Specifics for that question. Use the activities there to pinpoint gaps, problems, or weaknesses. Then move straight across to Take Action. Use the advice that suits your problem as you revise.

Take Action Strengthening Support for a Stand

169

Ask each question listed in the left-hand column to consider whether your draft might need work on that issue. If so, follow the ASK—LOCATE SPECIFICS—TAKE ACTION sequence to revise.

| 1ASK | 2LOCATE SPECIFICS | 3TAKE ACTION |

| Did I leave out any main points that I promised in my thesis or planned to include? |

|

|

| Did I leave out evidence needed to support my points—facts, statistics, expert testimony, firsthand observations, details, or examples? |

|

|

| Have I skipped over opposing or alternative perspectives? Have I treated them unfairly, disrespectfully, or too briefly? |

|

|

REVISION CHECKLIST

Have you developed your reasoning on a solid foundation? Are your initial assumptions sound? Do you need to identify, explain, or justify them?

Is your main point, or thesis, clear? Do you stick to it rather than drifting into contradictions?

Have you defined all necessary terms and explained your points clearly?

Have you presented your reasons for thinking your thesis is sound? Have you arranged them in a sequence that will make sense to your audience? Have you used transitions to introduce and connect them so readers can’t miss them?

Have you used evidence that your audience will respect to support each reason you present? Have you favored objective, research-based evidence (facts, statistics, and expert testimony that others can substantiate) rather than personal experiences or beliefs that others cannot or may not share?

170

Have you explained your evidence so that your audience can see how it supports your points and applies to your thesis? Have you used transitions to specify relationships for readers?

Have you enhanced your own credibility by acknowledging, rather than ignoring, other points of view or possible objections? Have you integrated or countered these views?

Have you adjusted your tone and style so you come across as reasonable and fair-minded? Have you avoided arrogant claims about proving (rather than showing) points?

Might your points seem stronger if arranged in a different sequence?

In rereading your paper, do you have any excellent, fresh thoughts? If so, where might you make room for them?

Have you credited any sources as expected by academic readers?

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Draft

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Draft

Reflecting on Your Draft

Reflect on a draft of a current essay that makes an argument. What have you found most challenging about the process of drafting an argument essay? What have you found most rewarding? How, if at all, has the work of producing multiple drafts caused you to rethink the argument or how you have constructed and supported it?

For more on editing and proofreading strategies, see Editing and Proofreading in Ch. 23.

After you have revised your argument, edit and proofread it. Carefully check the grammar, word choice, punctuation, and mechanics—and then correct any problems you find. Wherever you have given facts and figures as evidence, check for errors in names and numbers.

EDITING CHECKLIST

For more help, find the relevant checklist sections in the Quick Editing Guide and Quick Format Guide.

A6Is it clear what each pronoun refers to? Does each pronoun agree with (match) its antecedent? Do pronouns used as subjects agree with their verbs? Carefully check sentences that make broad claims about everyone, no one, some, a few, or some other group identified by an indefinite pronoun.

A7Have you used an adjective whenever describing a noun or pronoun? Have you used an adverb whenever describing a verb, adjective, or adverb? Have you used the correct form when comparing two or more things?

C1Have you set off your transitions, other introductory elements, and interrupters with commas, if these are needed?

171

D1, D2Have you spelled and capitalized everything correctly, especially names of people and organizations?

C3Have you correctly punctuated quotations from sources and experts?

Recognizing Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies are common mistakes in thinking that may lead to wrong conclusions or distort evidence. Here are a few familiar logical fallacies.

| Term | Explanation | Example |

| Non Sequitur | Stating a claim that doesn’t follow from your first premise or statement; Latin for “it does not follow” | Jenn should marry Mateo. In college he got all A’s. |

| Oversimplification | Offering easy solutions for complicated problems | If we want to end substance abuse, let’s send every drug user to prison for life. (Even aspirin users?) |

| Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc | Assuming a cause-and-effect relationship where none exists, even though one event preceded another; Latin for “after this, therefore because of this” | After Jenny’s black cat crossed my path, everything went wrong, and I failed my midterm. |

| Allness | Stating or implying that something is true of an entire class of things, often using all, everyone, no one, always, or never | Students enjoy studying. (All students? All subjects? All the time?) |

| Proof by Example or Too Few Examples | Presenting an example as proof rather than as illustration or clarification; overgeneralizing (the basis of much prejudice) | Armenians are great chefs. My neighbor is Armenian, and can he cook! |

| Begging the Question | Proving a statement already taken for granted, often by repeating it in different words or by defining a word in terms of itself | Rapists are dangerous because they are menaces.Happiness is the state of being happy. |

| Circular Reasoning | Supporting a statement with itself; a form of begging the question | He is a liar because he simply isn’t telling the truth. |

| Either/Or Reasoning | Oversimplifying by assuming that an issue has only two sides, a statement must be true or false, a question demands a yes or no answer, or a problem has only two possible solutions (and one that’s acceptable) | What are we going to do about global warming? Either we stop using all of the energy-consuming vehicles and products that cause it, or we just learn to live with it. |

|

172 |

Using an unidentified authority to shore up a weak argument or an authority whose expertise lies outside the issue, such as a television personality selling insurance | According to some of the most knowing scientists in America, smoking two packs a day is as harmless as eating oatmeal cookies. |

| Argument Ad Hominem | Attacking an individual’s opinion by attacking his or her character, thus deflecting attention from the merit of a proposal; Latin for “against the man” | Diaz may argue that we need to save the polar bears, but he’s the type who gets emotional over nothing. |

| Argument from Ignorance | Maintaining that a claim has to be accepted because it hasn’t been disproved or that it has to be rejected because it has not been proved | Despite years of effort, no one has proved that ghosts don’t exist; therefore, we should expect to see them at any time.No one has ever shown that life exists on any other planet; clearly the notion of other living things in the universe is absurd. |

| Argument by Analogy | Treating an extended comparison between familiar and unfamiliar items, based on similarities and ignoring differences, as evidence rather than as a useful way of explaining | People were born free as the birds; it’s cruel to expect them to work. |

| Bandwagon Argument | Suggesting that everyone is joining the group and that readers who don’t may miss out on happiness, success, or a reward | Purchasing the new Global Glimmer admits you to the nation’s most elite group of smartphone users. |