Learning from Other Writers: Observing the Titanic

Instructor's Notes

To assign the questions that follow this reading, click “Browse More Resources for this Unit,” or go to the Resources panel.

Observing the Titanic

Multiple Editors

Photo Essay

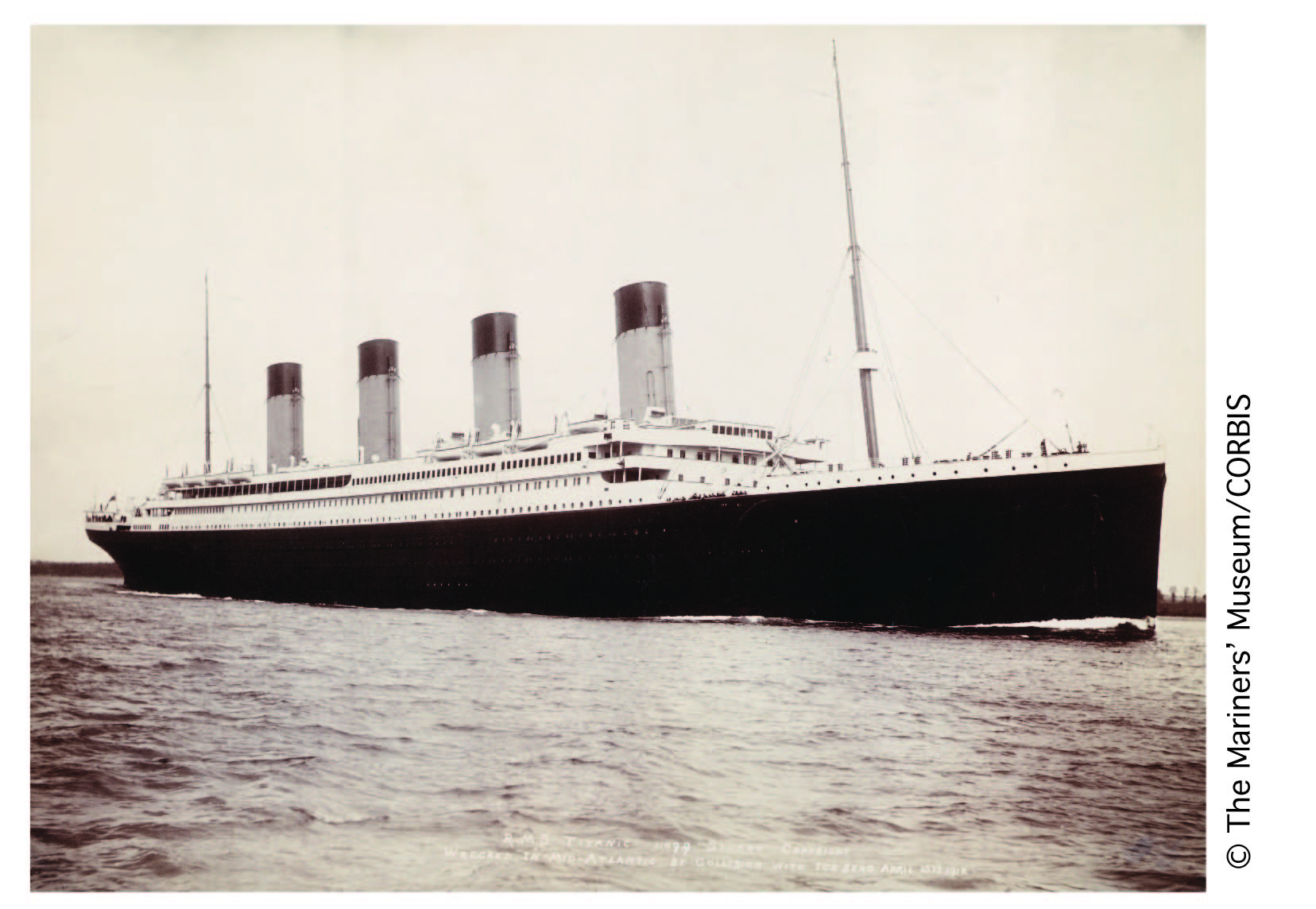

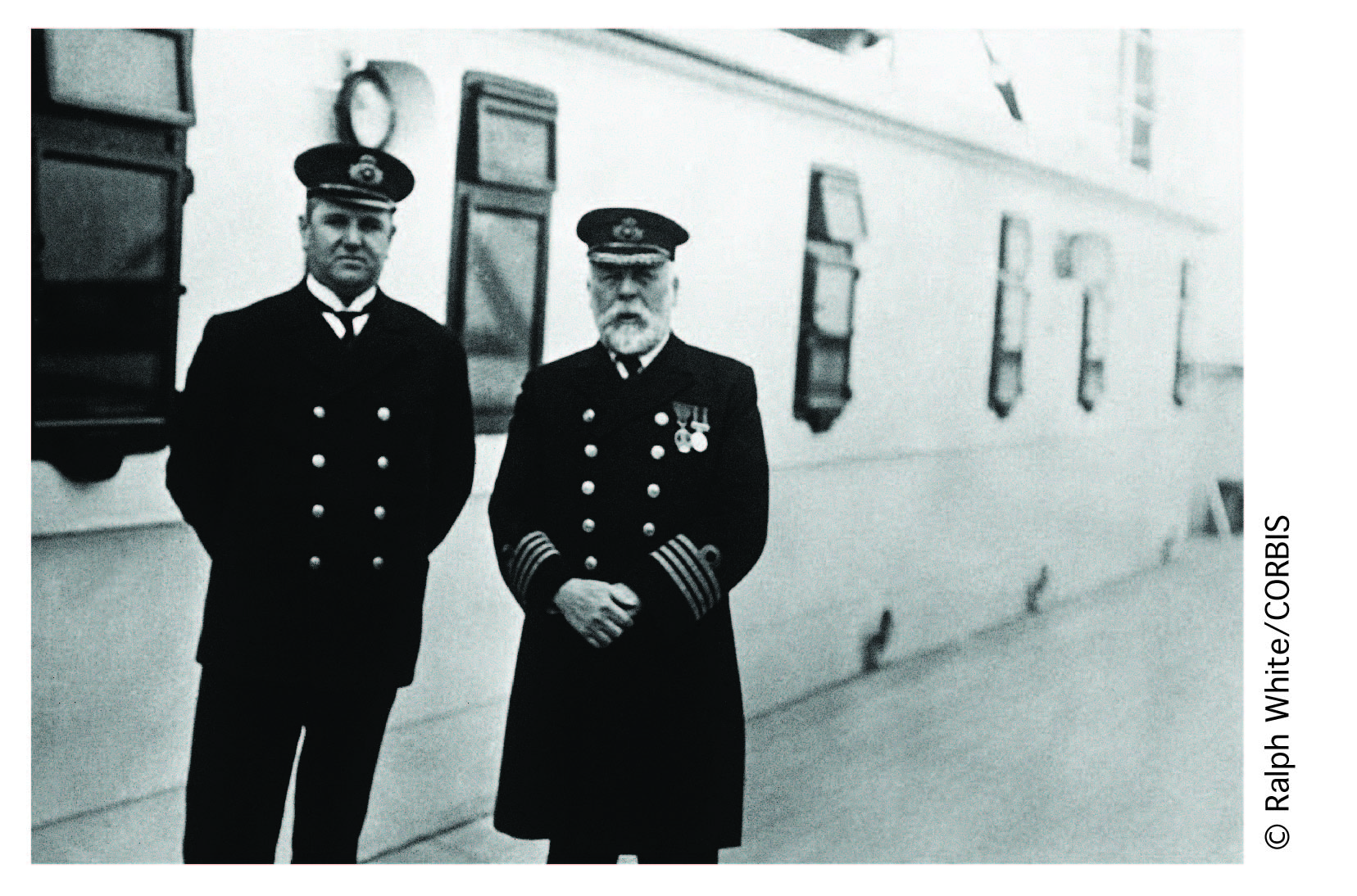

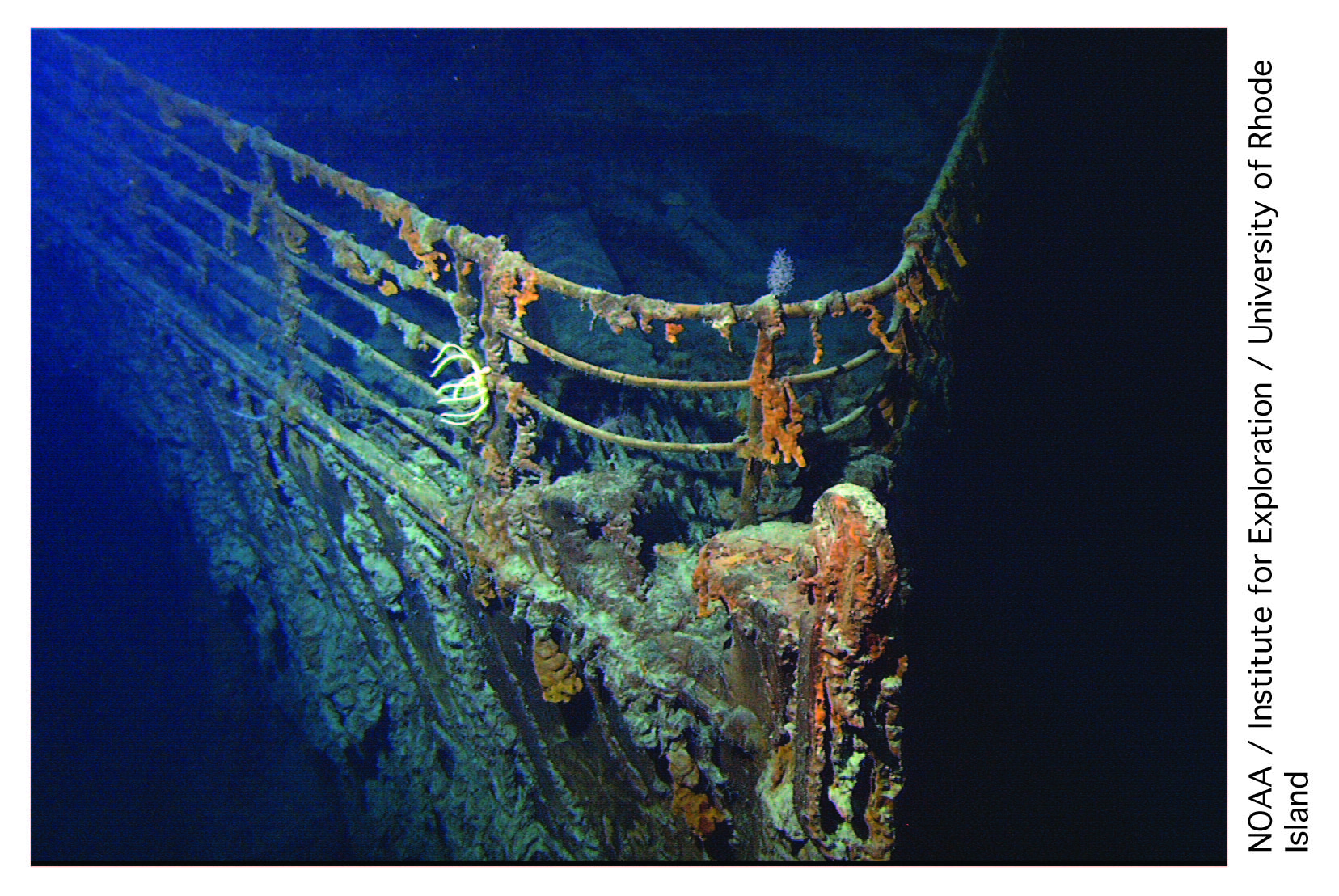

On its maiden voyage from Southampton, United Kingdom, to New York, United States, in April 1912, the RMS Titanic hit an iceberg off Newfoundland and sank within three hours, killing more than 1,500 people. Approximately 700 passengers and crewmembers were rescued. Seventy-three years later, in 1985, the wreck was discovered lying two and a half miles beneath the Atlantic’s surface, by a U.S.-French team led by Robert Ballard of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Many explorers and scientists have visited the Titanic since, including filmmaker James Cameron. Click through the photos to observe scenes of the luxurious ocean liner, then and now, and then answer the questions below.

Questions to Start You Thinking

Meaning

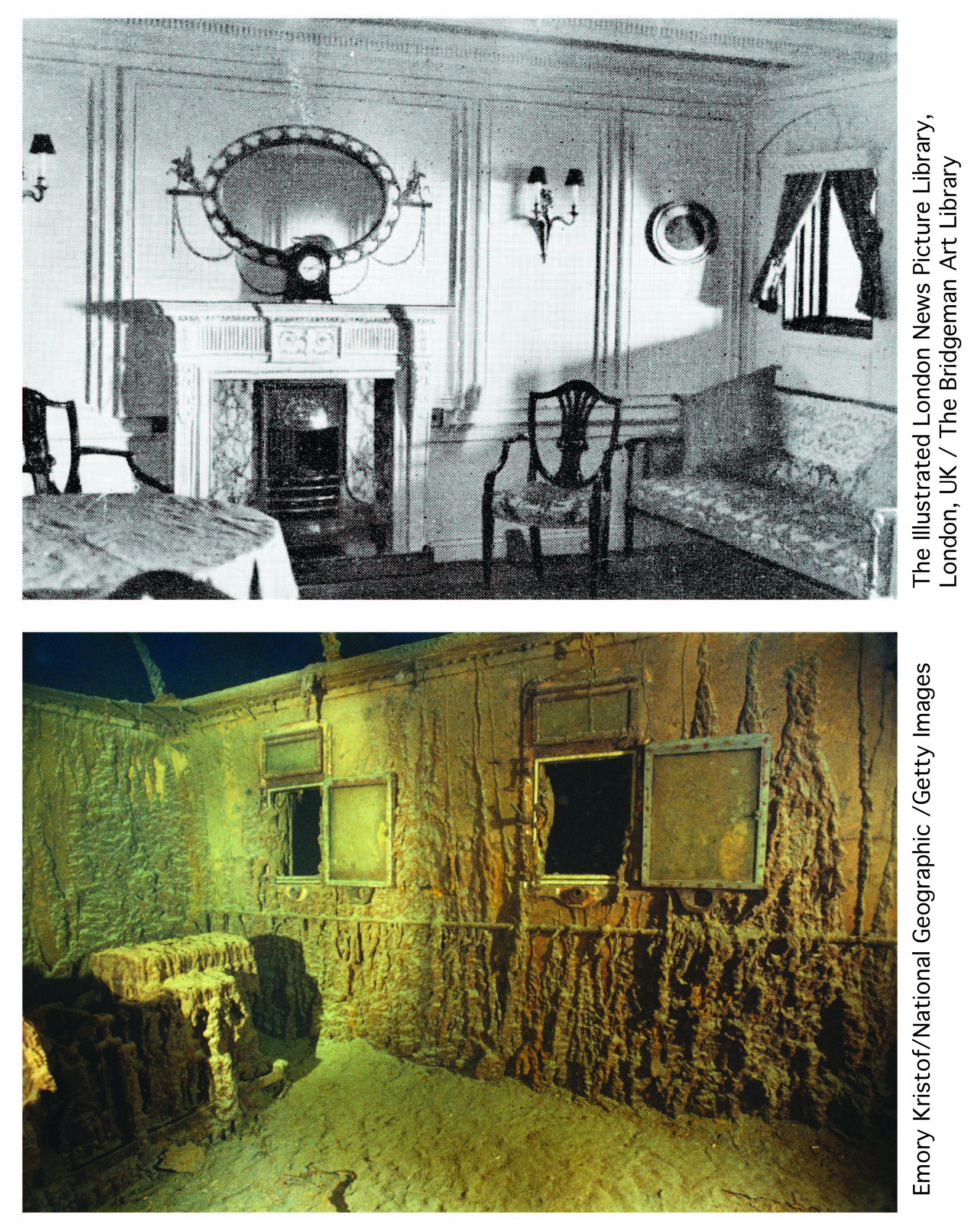

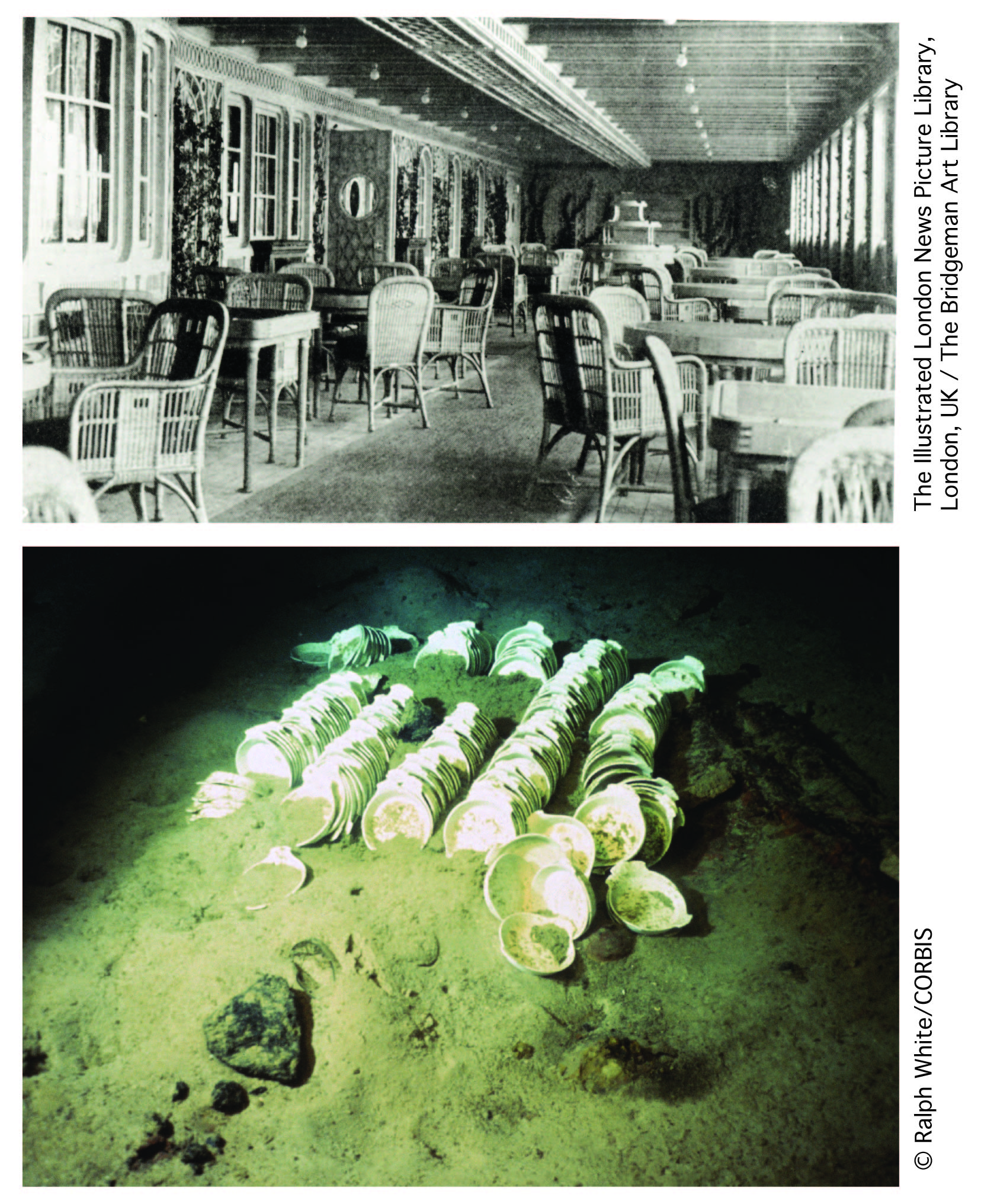

- The Titanic was known in its day as a magnificent floating palace, filled with gracious, extravagant touches. Observe and compare the two photos of private luxury suites, from 1912 and the present. What has stayed the same about the Titanic since it sank? What has changed about it? What effects have the 100 years under water had?

- Why would the Titanic have had so many luxurious touches, like the marble fireplaces, spacious bedrooms, fine dishes, and Parisian-style cafes, but not enough lifeboats for all the passengers?

- Survival rates varied by class and category. (Exact counts differ among sources and accounts): Among crewmembers, 693 died, and 213 were saved. Among third-class passengers, 532 died, and 181 were saved. Among second-class passengers, 166 died, and 118 were saved; and among first-class passengers, 197 were saved, and 123 died.

When the Titanic sank in 1912, why do you think that newspaper accounts at the time paid much attention to the prominent men who had lost their lives and less attention to the many European immigrants and average working-class and middle-class passengers? What do you think of the “women and children first” policy in place at the time?

Writing Strategies

- What is the effect of including captions that tell stories about life on board the Titanic? Did you find these captions helpful in understanding the photos? Why or why not?

- Does the photo essay showing images of the Titanic make you want to go on an ocean cruise or not? Make your case one way or the other using details from the photos.

- Contemporary Irish writer Jack Wilson Foster has commented, “We are all passengers on the Titanic.” What do you think he means by this statement? Do you agree? Why or why not?