10.1 Emerging into Adulthood

As you learned in Chapter 1, emerging adulthood is not a universal life stage. It exists for a minority of young people—those living at this point in history in the Western world. Its function is exploration—trying out options before committing to adult roles. Emerging adults often are “not quite ready” to settle down. They don’t feel financially or emotionally secure. They may be exploring trial pathways—moving from job to job, entering and then exiting college or a parent’s home, testing out relationships before they commit (Arnett, 2007; Arnett & Tanner, 2010).

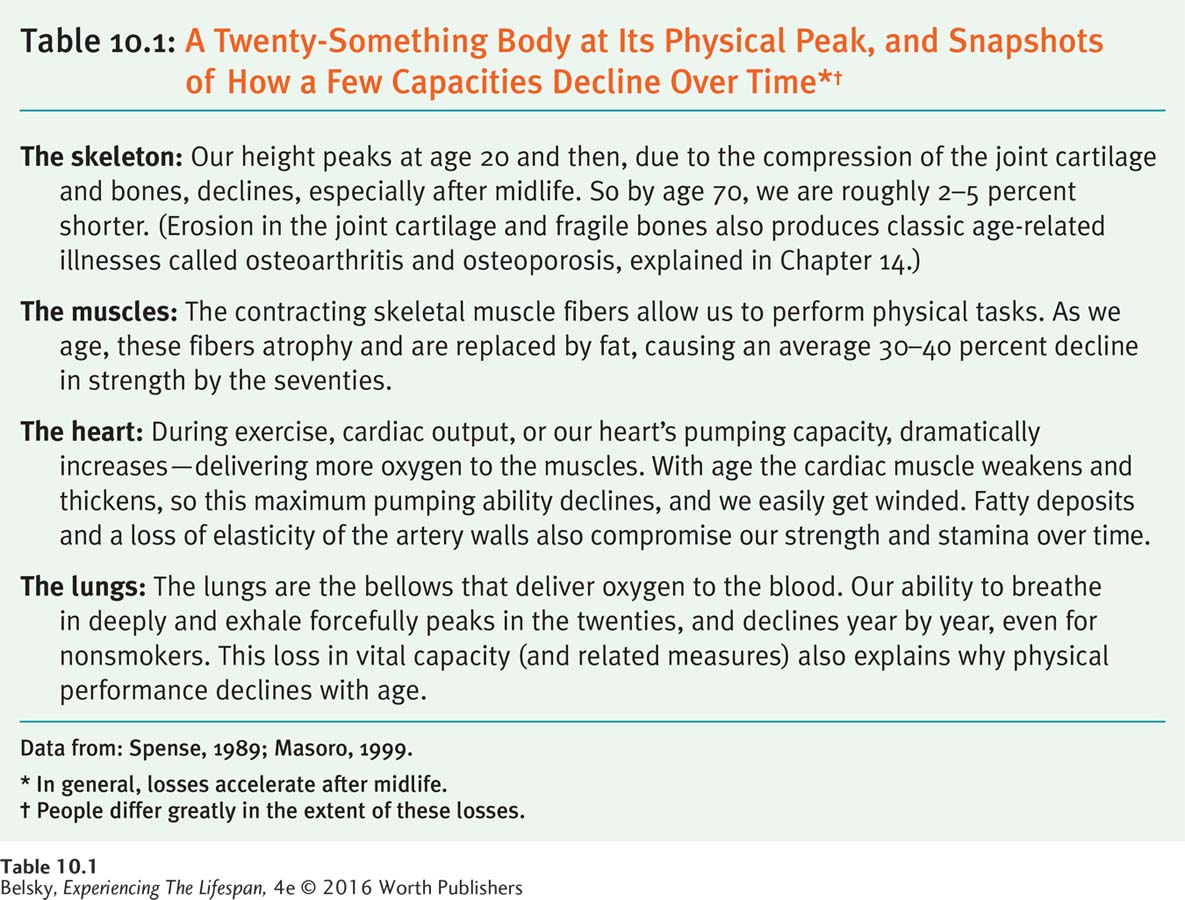

Emerging adulthood is defined by testing out different possibilities and developing the self. Its other core quality, according to Arnett, is often exuberant optimism about what lies ahead (Tanner & Arnett, 2010). Emerging adults, as Table 10.1 shows, are at their physical peak. Their abilities to think and to reason are in top form. Still, the challenges of this age are perhaps more daunting than those we face at any time of life.

We need to re-center our lives. Our parents protect us during adolescence. Now, our task is to take control of ourselves and act like “real adults” (Tanner, 2006; Tanner & Arnett, 2010). We used to count on the standard roles of marriage or supporting a family to make us feel adult. No more! Parents in collectivist countries such as China disagree with their developed world counterparts, viewing the core characteristics of adulthood in relational terms—such as keeping the family safe (see Nelson and others, 2013). But, Westerners view the benchmarks of adulthood in internal ways: Being adult means accepting responsibility. Adults financially support themselves. Adults make their own independent decisions about life (Arnett, 2007).

We have entered an unstructured, unpredictable path. During adolescence, high school organizes our days. We wake up, go to class; we are on an identical track. Then, at age 18, our lives diverge. Many of us go to college; others enter the world of work. Some people get married; others never enter that state. Emerging adults live alone or with friends, stay with their parents or move far away. For some emerging adults, constructing an adult life takes decades. For others—people who have children, get married, and enter the work world at age 18 or 19—there may be no life stage called emerging adulthood at all. So emerging adulthood is defined by variability—as we each set sail on our own. Why did this structure-free life stage emerge?

Setting the Context: Culture and History

Emerging adulthood was made possible because of our dramatic twentieth-century longevity gains. Imagine reaching adulthood a half-century ago. With a life expectancy in the mid-sixties, you could not have the luxury of spending almost a decade constructing an adult life. Now, with life expectancy floating up to the late seventies in industrialized nations, putting off adult commitments until an older age makes excellent sense.

Emerging adulthood was solidified by the need for more education. A half-century ago, high school graduates could climb to the top rungs in their careers. Today, in the United States, college is often crucial to adult success (Danziger & Ratner, 2010; Furstenberg, 2010). But, although most emerging adults enter college, it typically takes six years to get an undergraduate degree, especially because so many people need to work to finance school. If we add in graduate school, constructing a career can normally take until the mid-twenties and beyond (Johnson, Crosnoe, & Elder, 2011).

Emerging adulthood was promoted by uniquely individualistic attitudes about what makes for a satisfying adult life (Côté & Levine, 2002; Yeung & Hu, 2013). This life-stage took hold in a late-twentieth-century Western culture that stresses self-expression and “doing your own thing,” in which people make dramatic changes throughout their adult years.

Longevity, the need for education, and a Western ethic that stresses personal freedom made emerging adulthood possible. Still, the forces that drive this life stage vary from place to place. For snapshots of this variability, let’s travel to southern Europe, Scandinavia, and then enter the United States.

The Mediterranean Model: Living with Parents and Having Trouble Making the Leap to Adult Life

Many Greek men in their late twenties and thirties are still living with their families, in some cases because they cannot afford to the leave the nest and construct an adult life. If you were in this situation, how would you react?

Klaus Vedfelt/Taxi/Getty Images

In southern Europe, sagging economies make it difficult for young people to find jobs. The Italian and Spanish cultures, in particular, have norms against cohabitation, or living together (Seiffge-Krenke, 2013). People only push to leave home when they find a serious romantic partner and can support a spouse. This means young people in Portugal, Italy, Spain, and Greece often spend their emerging-adult years in their parents’ house (Mendonça & Fontaine, 2013; Seiffge-Krenke, 2013). Unfortunately, in Mediterranean nations, at the time of this writing (early 2015), family traditions, plus financial constraints, have seriously impeded young people’s travels into an independent life.

The Northern European Plan: Expect to Live Independently, Hopefully with Government Help

These impediments do not exist in northern European nations, where the economy is better (again, as of this writing) and where young people often live together and can have babies outside of marriage. In Norway, Sweden, and Denmark the government subsidizes university attendance. A strong social safety net provides free health care and other benefits to citizens of every age. So (although the reality can be different) in northern Europe, nest-leaving—moving out of a parent’s home to live independently—traditionally begins at the brink of the emerging-adult years (Furstenberg, 2010; Hendry & Kloep, 2010; Seiffge-Krenke, 2013). In the Nordic countries, in particular, the twenties are a stress-free interlude—a time for exploring, for testing out different relationships and careers before settling down to adult life (Buhl & Lanz, 2007).

The United States: Alternating Between Independence and Dependence

Emerging adulthood in the United States has features of both the northern European and Mediterranean scenes. As in northern Europe, in the United States, young people often live together and increasingly have children before they get married. Our individualistic culture has traditionally encouraged moving out of a parent’s home at 18. However, as in southern Europe, the United States does not help young people find work and has its own sluggish economy, so it can be difficult to exit the nest (more about this issue in the next section).

The reality is that our dramatic income inequalities, plus diversity of cultures, make U.S. young people emerging into adulthood very different at the starting gate (Furstenberg, 2010). We also have a more erratic passage to constructing an adult life (Settersten & Ray, 2010).

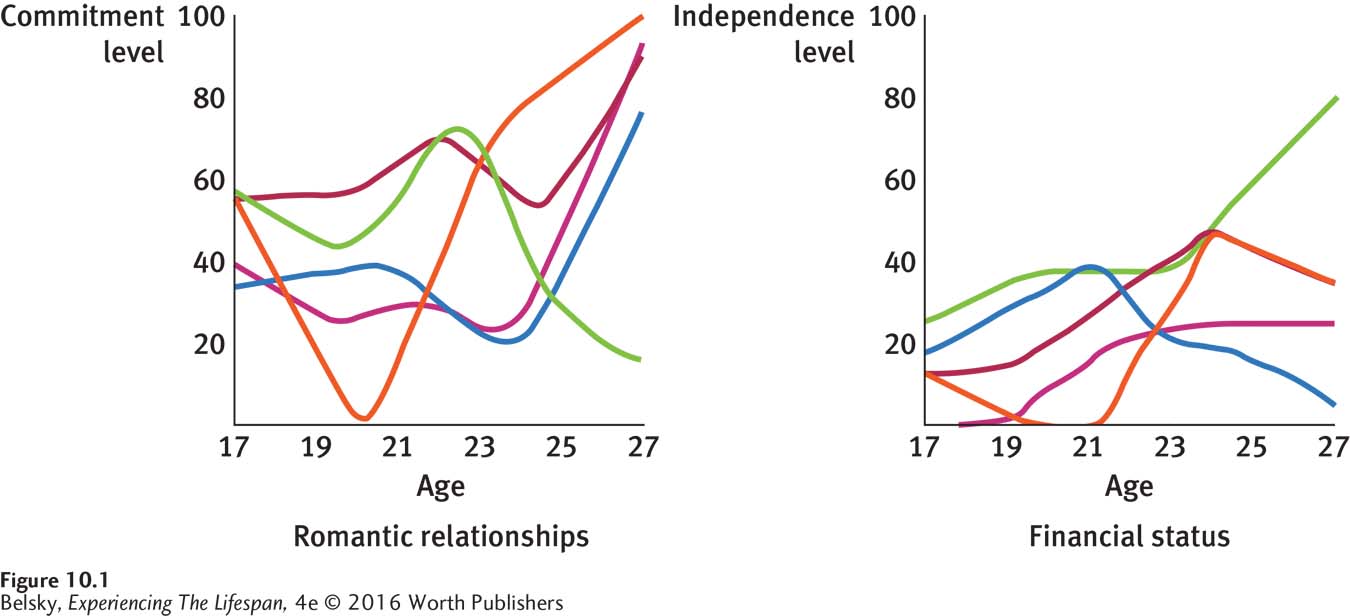

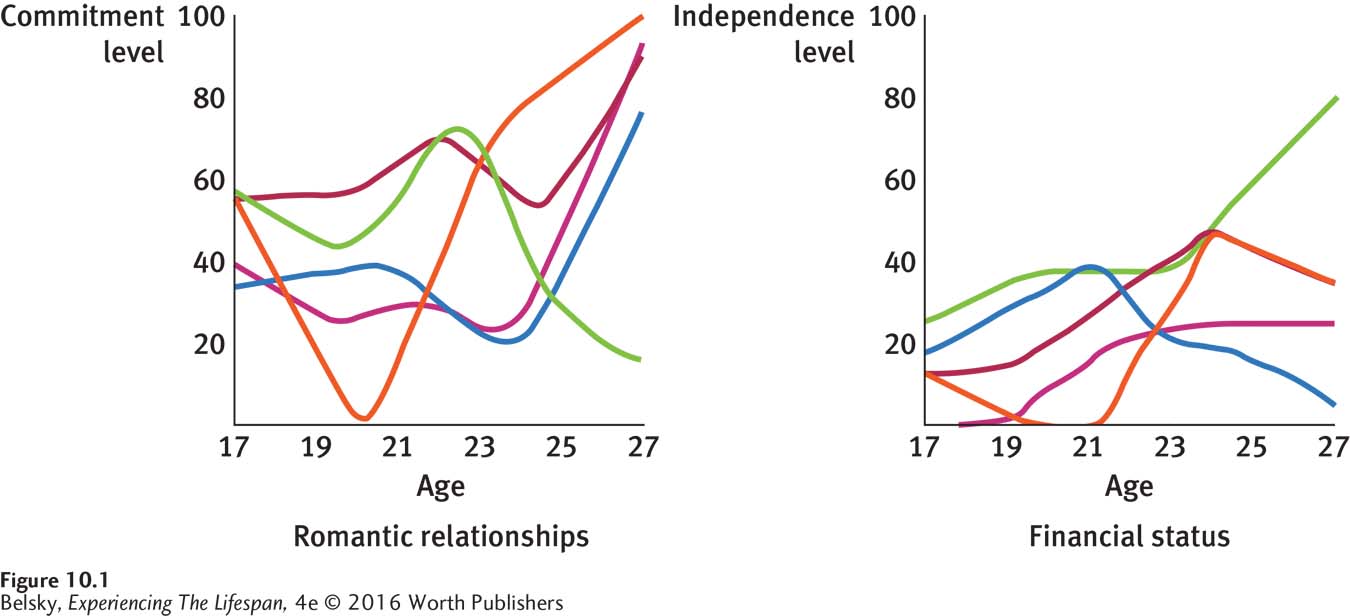

This bumpy path became evident several decades ago when researchers tracked several hundred New York State young people from ages 17 to 27, looking at their progress toward reaching classic adulthood markers such as financial independence, marriage, and living on their own (Cohen and others, 2003). Yes, there was an overall shift to more mature adult status as people moved deeper into their twenties. But notice from Figure 10.1 that, when we look at individuals, we see variability and movement backward and forward toward the benchmarks of being adult.

Figure 10.1: The ups and downs of the emerging-adult years: In a 10-year study tracing how young people develop from age 17 to 27, researchers discovered that many emerging adults move backward and forward on their way to constructing an adult life. These graphs illustrate the adult pathways of five different people in the areas of financial independence and romantic relationships.

Data from: Cohen and others, 2003.

So, at age 22, a man might be cohabiting with the idea of getting married. At 25, he might break up with his fiancée and begin dating again. A woman could be financially independent at 21, then slide backward, depending on her parents’ help after losing her job and returning to school.

If you are in your mid- or upper-twenties, think about your progress to adulthood in terms of relationships, career, and becoming financially independent. Does your pathway also show these ups and downs? When do you expect to fully arrive at adulthood?

Beginning and End Points

This last question brings up an interesting issue: When does emerging adulthood begin and end?

Exploring the “So-Called” Entry Point: Nest-Leaving

If you are like many middle-class Westerners, you might mark the event that launches emerging adulthood as moving out of a parent’s home. Leaving home after high school for college, a job, or—if your parents are affluent—a gap year traveling the world is often viewed as a rite of passage. It forces people to take that first step toward independent adulthood—taking care of their needs on their own. It also causes a re-centering in family relationships, as parents see their children in a different, adult way. Listen to this British mother gushing about her 20-year-old daughter: “To be honest I’m real proud of her. . . . She keeps her flat tidy which was a total shocker to me; I’d expected to be a laundry and maid service to her but fair play, she’s done all her washing and cleaning” (quoted in Kloep & Hendry, 2010, p. 824).

This quotation hints at two potential benefits of leaving home: It should produce more harmonious family relationships; it should force young people to “grow up.”

For this mother, being invited to her daughter’s first apartment may be a thrilling experience: “My baby did grow up to become a responsible woman!”

© Jose Luis Pelaez, Inc./Blend Images/Corbis

DOES LEAVING HOME PRODUCE BETTER PARENT–CHILD RELATIONSHIPS? U.S. research suggests the answer to this common perception is yes. In several longitudinal studies, both young people and their parents reported less conflict and more adult-to-adult relationships when college-bound children left the nest (Whiteman, McHale, & Crouter, 2007; Morgan, Thorne, & Zubriggen, 2010). However, this is not the case in Portugal, where family dependence is prized and staying at home is “normal” during the emerging-adult years. In this nation, where more than one-half of all people between the ages of 18 and 35 live with their parents, one study showed that staying in the nest had no impact on parent–child relationships. Ironically, Portuguese parents got more agitated when their children moved out! (See Mendonça & Fontaine, 2013.)

I must emphasize that, even in the United States, physically leaving home does not mean having distant family relationships. Judging by the 24/7 texts that fly back and forth between my students and their mothers, the impulse to stay closely connected to parents is more intense among this cohort of twenty-somethings than when I was a college student decades ago (see Levine & Dean, 2012). Having close mother–child relationships and even calling each other frequently is correlated with adjusting well to college and homing in on a satisfying career (Gentzler and others, 2011; Melendez & Melendez, 2010; Stringer & Kerpelman, 2010). Although they may not be making the meals or doing the laundry, mothers in particular remain a vital support as young people exit the nest and travel into the wider world.

DOES LEAVING HOME MAKE PEOPLE MORE ADULT? Here, European studies imply the answer is yes. In the Portuguese research I just described, young people who lived on their own managed their lives more competently than did their peers who stayed in the nest (Mendonça & Fontaine, 2013). When Belgian researchers compared young people in their early twenties who never left home with a same-aged group who moved out, the “nest residers” were less likely to be in a long-term relationship, felt more emotionally dependent on their parents, and were less satisfied with life (Kins & Beyers, 2010; see also Seiffge-Krenke, 2010). One Belgian emerging-adult named Adam spelled his feelings out: “(It) is comparable to living in a hotel actually. I have no charges . . . my meals are prepared, my laundry is done” (quoted in Kins, de Mol, & Beyers, 2014, p. 104). Another British mom put it more graphically: “He is my little boy, a mummy’s boy if you like. . . . And ’cos he lives at home still . . . I do his clothes, his washing, tidy his room . . . and even still do packed lunch for him to take to work” (quoted in Kloep & Hendry, 2010, p. 826).

These quotations reinforce our negative images about emerging adults who stay in the nest (yes, in the developed world, they tend more often to be males): They are lazy, babyish, and unwilling to grow up. The problem is that we are confusing consequences with causes. In southern Europe, the push to move out is often propelled by finding a serious romantic relationship (“Now that I found my life love, I must leave home!”). In every nation, as I implied earlier, nest-leaving has a clear economic cause (Seiffge-Krenke, 2013). Young people stay at home, or return to live with their families, because they cannot afford to live on their own (Berzin & De Marco, 2010; Britton, 2013).

This college student is living at home to save money. How can she and her mother negotiate the difficult task of getting along as adults? Stay tuned for suggestions right now.

Iakov Filimonov/Shutterstock

In addition to economic issues, there is another barrier to moving out for some immigrant and ethnic minority youth—values (Furstenberg, 2010; Kiang & Fuligni, 2009). If a young person’s collectivist worldview says, “put family first,” or if a family really needs help, children may stay in the nest for very adult-centered reasons—to help with the finances and the chores. As one Latino 20-year-old explained: “I can’t leave my mom by herself, she is a single mother. The only person she’s got is me. . . .” (quoted in Sánchez and others, 2010, p. 872).

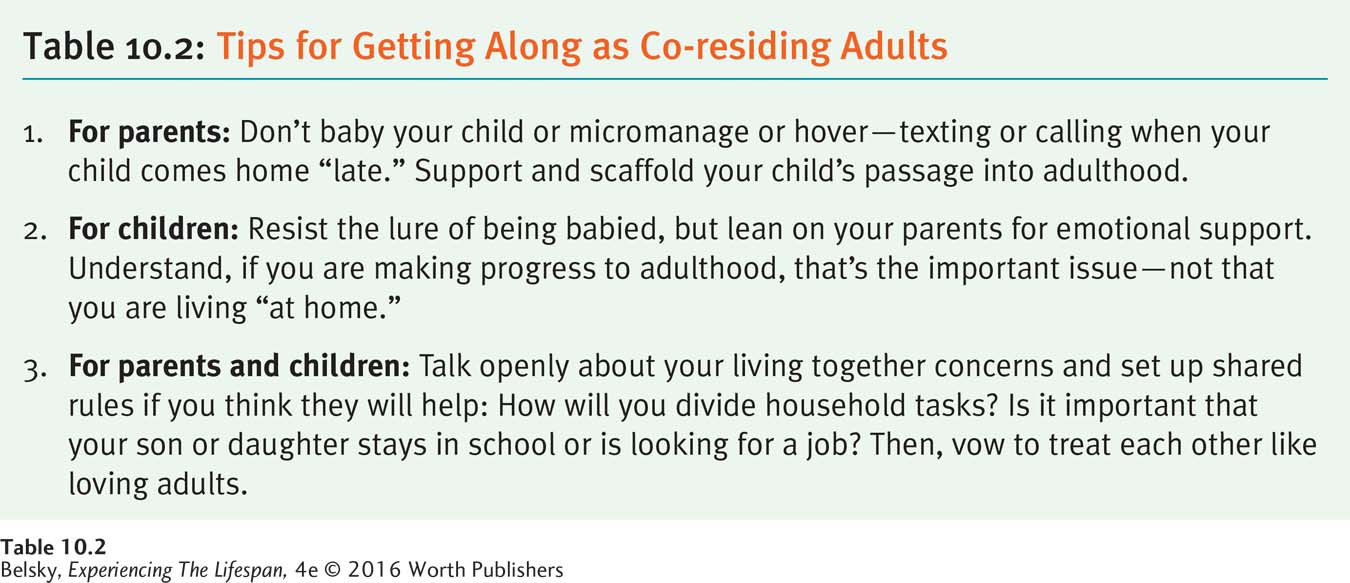

So, does nest-leaving qualify as the entry point of emerging adulthood? The answer is “not really anymore.” Do young people need to live independently to act mature? The answer is definitely no. The real challenge for families is to construct adult-to-adult relationships with their children no matter where the younger generation lives (see Table 10.2 for some suggestions). And the challenge for young people is to assemble the building blocks to construct a satisfying adult life. When should this constructing phase end and full adulthood arrive? The answer brings up a classic concept in adult development.

Exploring the Fuzzy End Point: The Ticking of the Social Clock

When this not-so-young man in his forties finally proposed to his long-time, 38-year-old girlfriend, she and her family were probably thrilled. Feeling “off time” in the late direction in your social-clock timetable can cause considerable distress.

Volt Collection/Shutterstock

Our feelings about when we should get our adult lives in order reflect our culture’s social clock (Neugarten, 1972, 1979). This phrase refers to shared age norms that act as guideposts to what behaviors are appropriate at particular ages. If our passage matches up with the normal timetable in our culture, we are defined as on time; if not, we are off time—either too early or too late in terms of where we should be at a given age.

So in the twenty-first-century West, exploring different options is considered “on time” during our twenties, but these activities become off time if they extend well into the next decade of life. A parent whose 39-year-old son is “just dating” and shows no signs of deciding on a career or moves back home for the third or fourth time may become impatient: “Will my child ever grow up?” A woman traveling through her thirties may get uneasy: “I’d better hurry up if I want a family,” or “Do I still have time to go to medical school?”

Society sets the general social-clock guidelines. Today, with the average age of marriage in most E.U. countries floating up to the late twenties for women and the early thirties for men (Shulman & Connolly, 2013), it’s fine to date for more than a decade if you live in the West. But in China, everyone is expected to get married, and the marriage age is lower now than in the past (Yeung & Hu, 2013). So, in Beijing, it’s shameful, as a female, to be over age 30 without a mate: “The older generation cannot understand why I keep being single . . . ,” said one woman. “Many people will think . . . I must have some mental or physical deficiencies” (quoted in Wang & Abbott, 2013, p. 226).

For a surprising number of people, coping with the demands of college can seem like an insurmountable challenge. You need to struggle with the anxious feeling of “can I make it academically?” plus take responsibility for handling all those fast-paced deadlines, all on your own. This shock of first bumping up against adult realities helps explain why—as you will see later—many college freshmen report high levels of emotional distress.

© Myrleen Pearson/PhotoEdit

Personal preferences make a difference, too. In one survey, developmentalists found that they could predict a given student’s social-clock timetable by asking a simple question: “Is having a family your main passion?” People who said that “marriage is my top-ranking agenda,” or “I can’t wait to be a mom or dad,” often had an earlier timetable for entering adult life (Carroll and others, 2007). So, the limits of emerging adulthood are set both by the culture and shaped by our own priorities and goals.

The problem, however, is that our personal social-clock agendas are not totally under our control. You cannot simply “decide” to marry the love of your life at a defined age. This sense of being “out of control,” combined with the pressures to get our adult life in order, may explain why emerging adulthood is both an exhilarating and emotionally challenging time. On the positive side, most emerging adults are optimistic about their futures (Frye & Liem, 2011; Pryor and others, 2011). On the minus side, especially in the first year after entering college emotional distress can be intense (Pryor and others, 2011).

For many young people, the issue lies in failing at the task of taking adult responsibility. As one emerging adult anguished: “My life looks like a . . . gutter and effort to fight that gutter . . . then back in the gutter . . . I just don’t have any control over myself” (quoted in Macek, Bejcek, & Vanickova, 2007, p. 466). For others, concerns center around balancing multiple commitments, such as the need to work full time and go to school. Or, some emerging adults may have the feeling of not knowing where they are going in life: “We do have more possibilities . . . but that’s why it’s harder” . . . “You study and you wonder what it is good for” (quoted in Macek, Bejcek, & Vanickova, 2007, p. 468). The reason for this inner turmoil is that, during emerging adulthood, we undergo a mental makeover. We decide who to be as adults.