11.1 Marriage

Ask people to describe their ideal marriage (or relationship) and you may hear phrases such as “soul mates,” “equal sharing,” and “someone who fulfills my innermost self” (Amato, 2007; Dew & Wilcox, 2011). This vision of “lovers for life,” who work and share the housework equally, is a product of living in the contemporary, developed world.

Setting the Context: The Changing Landscape of Marriage

Throughout history, as I implied in Chapter 10, people often got married based on practical concerns. With marriages often being arranged by the couple’s parents, and daily life being so difficult, we did not have the luxury of marrying for love. In addition, in the not-

Then, in the early twentieth century, as life got easier and health care advances allowed us to routinely live into later life, in Western nations, we developed the idea that people should get married in their twenties and be lovers for a half-

In the last third of the twentieth century, Western ideas about marriage took another turn. The women’s movement told us that women should have careers and spouses should share the child care. As a result of the 1960s lifestyle revolution, which stressed personal fulfillment, we rejected the idea that people should stay in an unhappy marriage. We could get divorced, have babies without being married, and choose not to get married at all.

The outcome was the dramatic change that social scientists call the deinstitutionalization of marriage (Cherlin, 2004, 2010). This phrase means that marriage has been transformed from the standard adult “institution” into an optional choice.

329

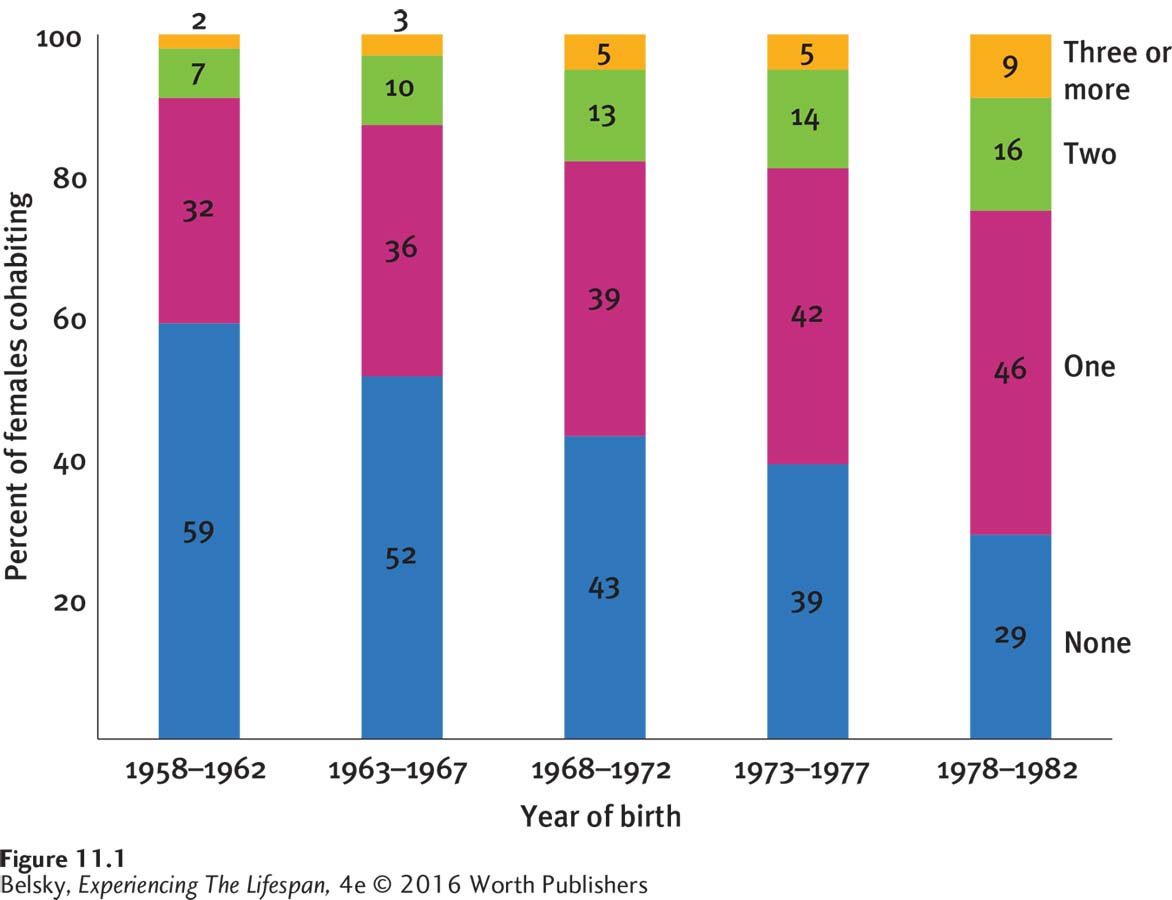

Figure 11.1 shows one symptom of this transformation in the United States: A steady cohort-

The most revealing change relates to serial cohabitation—living with different partners sequentially during adult life. When emerging adults cohabit with only one person, they are more apt to see this arrangement as a step to a wedding ring (“We want to see if we can make it as husband and wife”). Serial cohabiters are unlikely to have any marriage goals (Vespa, 2014). They may join the millions of contemporary women who give birth without a spouse.

This brings up the most controversial U.S. change: unmarried parenthood. During the 1950s, if a U.S. woman dared to have a baby without being married, her family might ship her off to a home for unwed mothers or insist that she marry the dad (the infamously named “shotgun marriage”). A half-

330

Acceptance of divorce, cohabitation, and unmarried motherhood clearly varies around the globe. How are these lifestyles playing out in countries famous for rigid marriage rules? For answers, let’s travel to Iran and India.

Iran: Eroding Male Dominated Marriage

When we imagine cultures most horrified by our “decadent” Western practices, countries such as Iran might come to mind. In Iran, in accordance with fundamentalist Islamic Law, marriage is the only acceptable life path. Moreover, Iran’s Civil Code includes provisions suggesting that women are subservient to men. A daughter should be pure—

Just as shocking to Western eyes were Iranian regulations surrounding divorce: Husbands have decision-

Within the past 15 years, these pronouncements lost force. Iranian women can now initiate divorce proceedings and draw up prenuptial agreements, spelling out their right to work; they can insist on getting half of the man’s property if the couple splits up.

Moreover, in recent decades, women in Iran made massive strides in moving into the wider world. In Iran today—

India: From Arranged Marriages to Eloping for Love

India is an even stronger “anti-

The most radical change relates to what people in India call elopements: Young people run away and get engaged without their parents’ consent. What typically happens here is that the girl leaves home without telling her parents (or the boy and girl both leave home). Then, the boy’s family goes to the girl’s family, informs them of her whereabouts and gets consent for the marriage. A few months later, unless the girl’s parents forbid the union, the couple formally weds (Allendorf, 2013).

331

What do people think about this change? For answers researchers traveled to a rural area of India to conduct interviews. While believing that each type of marriage had its pluses and minuses, most residents were in favor of elopements. Well-

India is miles from Western in its marriage views. However, in this nation, it seems appropriate to cite the lyrics, “The times they are a changing.”

Western Variations

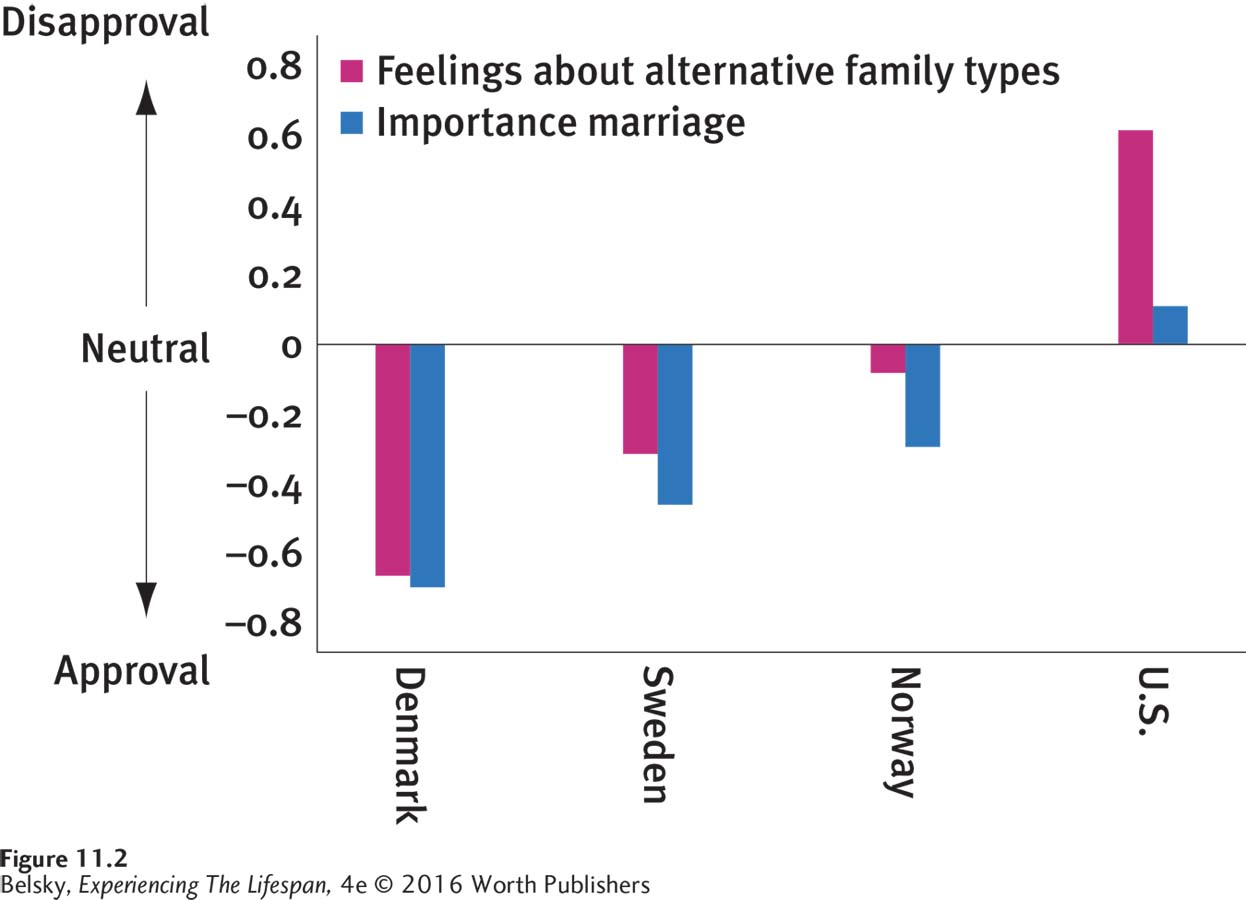

The deinstitutionalization of marriage is the melody now being played throughout the developed world. Still, as Figure 11.2 shows, attitudes toward alternate family forms differ from nation to nation in the West. Because the United States is ambivalent about unmarried motherhood, women who give birth without a wedding ring, particularly those who move from cohabiting relationship to relationship, are far more likely to be poor (Farber & Miller-

The reality is that the United States is still in love with marriage. Roughly 8 out of 10 U.S. young people want to eventually get married—

Think about your requirements for getting married if you are single—

332

Read what Candace, a 25-

Um, we have certain things that we want to do before we get married. We both want very good jobs. . . . He’s been looking out for jobs everywhere and we—

(quoted in Smock, Manning, & Porter, 2005, p. 690)

As this comment implies, rather than blaming a “culture of irresponsibility” (see Murray, 2012), the lack of well-

Another goal that seems hard to reach—

Is our dream of finding a life soul mate too idealistic, given that we never expected people to stay madly in love for 50 or more years? How can couples stay together for decades when there are so many alternatives to marriage today? In the next section, I’ll focus on this question as I explore the insights that research offers for having enduring, happy relationships. Let’s begin, however, by tracing how marital happiness normally changes through the years.

The Main Marital Pathway: Downhill and Then Up

Many of us enter marriage (or any romantic relationship) with blissful expectations. Then, disenchantment sets in. Hundreds of studies conducted in Western countries show that marital satisfaction is at its peak during the honeymoon and then decreases (Blood & Wolfe, 1960; Glenn, 1990; Lavner & Bradbury, 2010). As the decline—

Notice the interesting similarity to John Bowlby’s ideas about the different attachment phases. In the first year or two of marriage, couples are in the phase of clear-

The good news is that there is a positive change to look forward to later on. According to the U-

333

Happy elderly couples actually embody many of the good love-

This brings up individual differences. Many of you may know miserable, long-

Almost everyone gets married convinced the statistics don’t apply to them: “We are going to live happily ever after. Our relationship will improve over time, and it certainly won’t get worse.” Ironically, in tracking newly married couples, researchers found women who held these optimistic ideas to an extreme were at special risk of being disenchanted, or totally turned off, in the next few years (Lavner, Karney, & Bradbury, 2013).

Why might seeing one’s marriage—in particular—

What does it mean to constructively handle conflicts, and what other attitudes help us stay together happily for life? To offer some perspective on these issues let’s first spell out a familiar psychologist’s (that is, from his theory of intelligence, described in Chapter 7) conceptualizations about love—

The Triangular Theory Perspective on Happiness

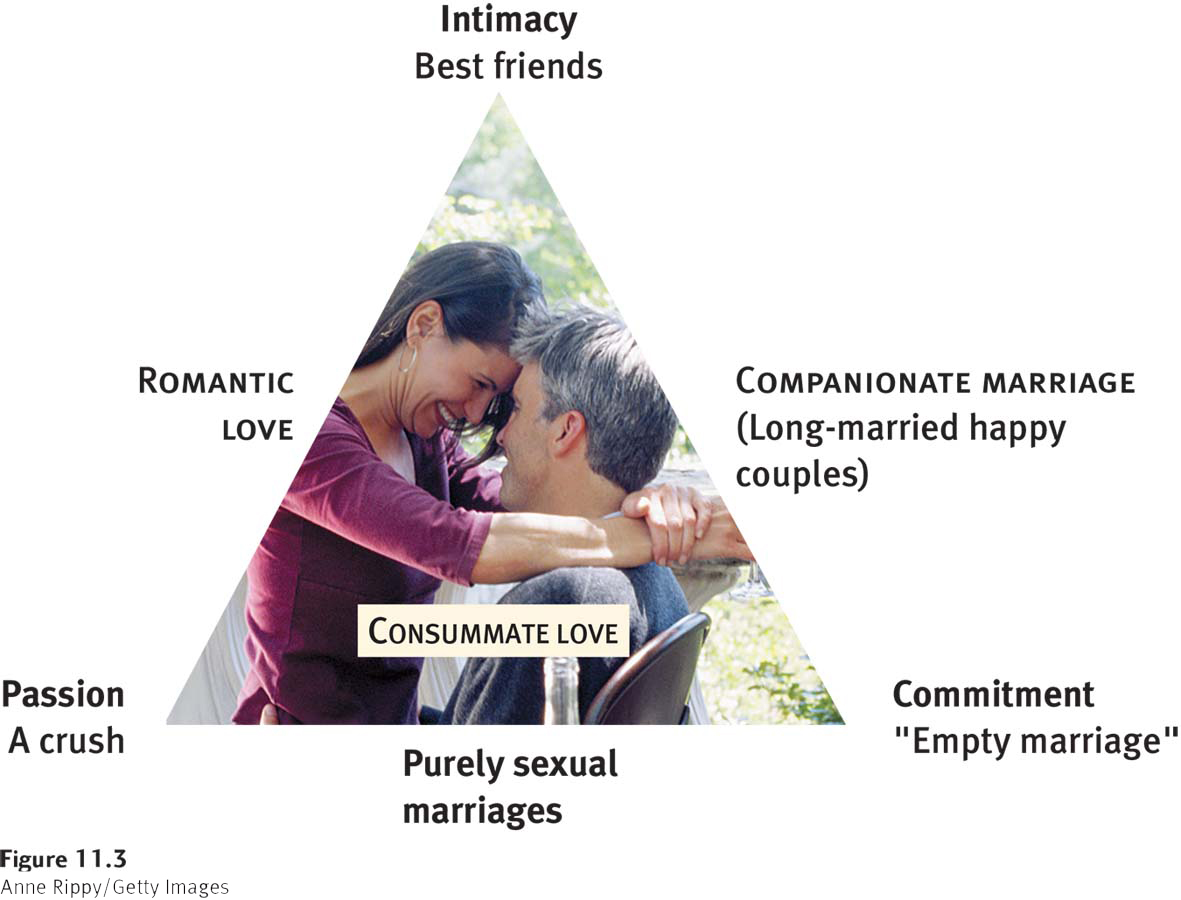

According to Sternberg’s (1986, 1988, 2004) triangular theory of love, we can break adult love relationships into three components: passion (sexual arousal), intimacy (feelings of closeness), and commitment (typically marriage, but also exclusive, lifelong cohabiting relationships). When we arrange them on a triangle such as Figure 11.3, as I’ll describe next, we get a portrait of the different kinds of relationships in life.

With passion alone, we have a crush, the fantasy obsession for the girl down the street or a handsome professor we don’t really know. With intimacy alone, we have the caring that we feel for a best friend. Romantic love combines these two qualities. Walk around your campus and you can see this relationship. Couples are passionate and clearly know each other well but have probably not made a commitment to form a lifelong bond.

334

On the marriage side of the triangle, commitment alone results in “empty marriages.” In these emotionally barren, loveless marriages (luckily, fairly infrequent today), people stay together physically but live separate lives. Intimacy plus commitment produces companionate marriages, the best-

Why is consummate love fragile? One reason is that, with familiarity, passion often falls off. It’s hard to keep lusting after your mate when you wake up together day after day for years (Klusmann, 2002). This sexual decline has an unfortunate hormonal basis. Married couples—

As couples enter into the working-

Sternberg’s theory beautifully alerts us to why marriages normally get less happy. But it does not offer clues as to how we can beat the odds and stay romantically connected for life. Actually, a fraction of couples (roughly 1 in 10 people) do stay passionate for decades (Acevedo & Aron, 2009). What are these marital role models doing right? For answers, researchers decided to decode the experience of falling in love.

When we fall in love, they discovered, efficacy feelings are intense. We feel powerful, competent, capable of doing wonderful things (Aron and others, 2002). Given that romantic love causes a joyous feeling of self-

To test this idea, the psychologists asked married volunteers to list their most exciting activities—

So, to stay passionate for decades, people may not need to take trips to Tahiti, or even have candlelit dinners with a mate. The secret is to continue to engage in the flow-

335

Commitment, Sanctification, and Compassion: The Core Attitudes in Relationship Success

But sharing exciting activities may not be sufficient to keep couples glued to one another during the stresses and storms of daily life. People must be committed to a spouse.

Researchers are passionate to identify the glue called “commitment,” the inner attitudes that keep couples hanging in happily together over years (Epstein, Pandit, & Thakar, 2013). One force that fosters commitment, they find, is believing one’s union is sanctified by god (“My marriage is an expression of god’s will”) (Stafford, David, & McPherson, 2014; Kusner and others, 2014). This conviction of being destined for a particular person—

I was committed to proving them [others’ predictions] wrong . . . somewhere along in trying to stay in there to prove everyone wrong, I fell in love. I probably should have fallen in love before I said “I do” . . . but I wasn’t you know . . . —it’s amazing!

(quoted in Hurt, 2013, p. 870)

But if you assume commitment means making the best of a relationship because there is no alternative (as in the lyrics, “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with”), you are wrong. Commitment involves immensely positive emotions, too.

Committed spouses are dedicated to a partner’s “inner growth” (Fincham, Stanley, & Beach, 2007; Overall, Fletcher, & Simpson, 2010). Specifically, commitment involves sacrifice, giving up one’s desires to further the other person’s joy. When people sacrifice for their partner, they are benefiting themselves. Drawing on our natural high from performing costly prosocial acts (recall Chapters 4 and 6), there is no greater joy than performing personally difficult acts for the people we love (Kogan and others, 2010).

Intrinsic to sacrifice is compassion, being devoted to the other person’s well-

Couple Communications and Happiness

Watch happy couples, whether they are age 80 or 18, and you will be struck with the way they relate. Like mothers and babies enjoying the dance of attachment, loving couples share joyous experiences. They are playful, affectionate. They use humor to signal, “I love you,” even when they disagree (Driver & Gottman, 2004). During disagreements, women in happy relationships regulate their emotions. They dampen down angry feelings rather than letting the situation get out of hand (Bloch, Haase, & Levenson, 2014).

336

But have you ever spent an evening with friends and had the uneasy feeling, “This relationship isn’t working out”? By listening to couples talk, psychologist John Gottman (1994, 1999) can tell, with uncanny accuracy, whether a marriage is becoming unglued. Here are three communication styles that distinguish thriving relationships from those with serious problems:

Happy couples engage in a high ratio of positive to negative comments. People can fight a good deal and still have a happy marriage. The key is to be sure that your caring comments strongly outweigh critical ones. In videotaping couples discussing problems in his “love lab,” Gottman has discovered that when the ratio of positive to negative interactions dips well below 5 to 1, the risk of getting divorced escalates.

Happy couples don’t get personal when they disagree. When happy couples fight, they confine themselves to the problem: “I don’t like it when I come home and the house is messy. What can we do?” Unhappy couples personalize their conflicts: They use put-

downs and sarcasm. They look disgusted. They roll their eyes. Expressions of contempt for a partner are poisonous to married life. Happy couples are sensitive to their partner’s need for “space.” Another classic way of interacting that signals a relationship is in trouble occurs when one person provides too much “support” (Brock & Lawrence, 2014). A husband gives his wife excessive advice about her clothes or raising the children; a wife intrusively micromanages her partner’s life. You would not be surprised to learn that these actions don’t qualify as compassion, even when a person says, “I’m doing this for your well-

being.” People who sensitively perform the dance of attachment— whether moms with infants or married couples— know when to be close and when to back off (Feeney & Noller, 2002; Murray and others, 2003; Brock & Lawrence, 2014).

INTERVENTIONS: Staying Together Happily for Life

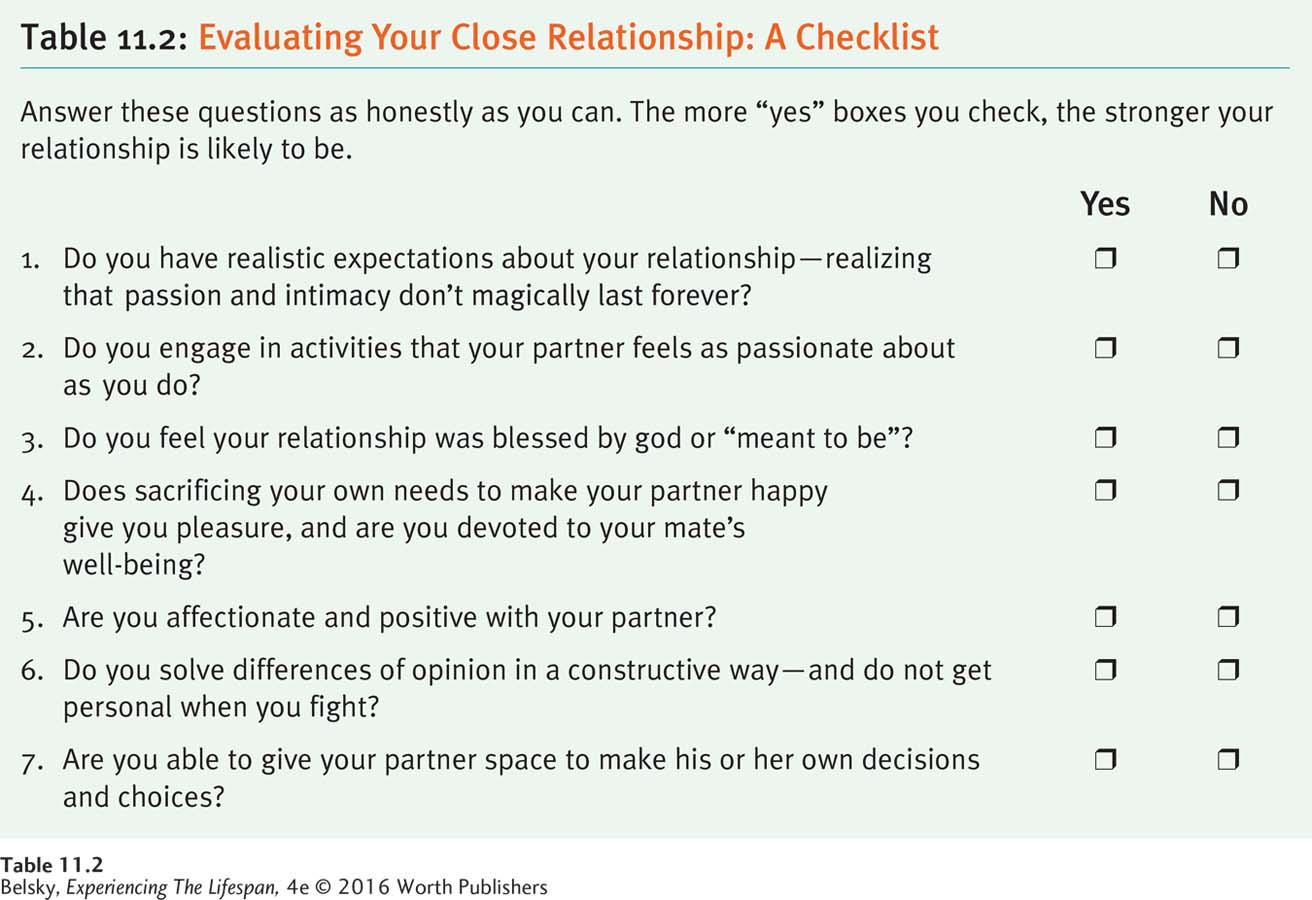

How can you draw on all of these insights to have an enduring, happy relationship? Understand the natural time course of love. Be fully committed to your partner. Act on that feeling by being devoted to the person’s development and taking joy in sacrificing for your mate. Preserve intimacy and passion by sharing arousing, exciting activities. Be very, very positive after you get negative. Avoid getting personal when you fight. Be sensitive to your partner’s need for space. Table 11.2 offers a checklist based on these points to evaluate your current relationship or to keep on hand for the love relationships you will have as you travel through life.

As a final caution, however, I must emphasize that commitment is sometimes misplaced. One key to sacrificing is reciprocity. If a relationship is totally one-

337

Divorce

Researchers stress that we need to think of divorce as having specific phases. When people consider this major life change, they weigh the costs of leaving against the benefits (Hopper, 1993; Kelly, 2000). You and your spouse are not getting along, but perhaps you should just hang on. One deterrent is financial: “Can I afford the loss in income after a divorce?” But if the couple has children, money issues are trumped by a more critical concern: “How will divorce affect my parenting?” “Will this damage my daughter or son?” (See Poortman & Seltzer, 2007; recall also Chapter 7.)

Couples typically cite communication problems like those I’ve been discussing, and lack of “attachment,” as the reasons for their divorce (Bodenmann and others, 2007). In extreme cases, women report being denigrated and completely controlled: “If I had a . . . contrary opinion,” (one woman complained) “then the reaction would be, ‘Well what do you know?’” (Adapted from Watson & Ancis, 2013, p.173.)

Once a couple separates, they experience an overload of changes: the need to move or perhaps find a better-

Still, divorce can produce emotional growth and enhanced efficacy feelings as people learn they can make it on their own (Fahs, 2007; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). And, of course, ending a marriage can come as a welcome relief (Montemurro, 2014). Perhaps aided by that burst of testosterone, some women rediscover their sexuality, too. Listen to a 58-

338

Who feels relieved or sexually energized after divorce? Insights come from considering why people separate. In one U.S. study tracking married couples, researchers put divorced couples into two categories: spouses who had reported being miserable in their marriage, and couples who divorced, even though they had previously judged their marital happiness as “fairly good” (Amato, 2010; Amato & Hohmann-

People in very unhappy marriages did feel liberated after divorcing. But relatively satisfied couples who later divorced, perhaps thinking, “I just don’t find our relationship fulfilling,” reported subsequent declines in well-

Hot in Developmental Science: Marriage the Second or Third or “X” Time Around

This brings up that common sequel to divorce: remarriage. Today, about 1 in 4 U.S. marriages occur between previously divorced partners, and almost 1 in 2 involve a spouse who has been married at least once before (see Shafer & James, 2013). Are people correct that they might do better the second or third time around?

Before considering the issue, let’s spell out some realities. If you are a woman, and especially if you have children (and are older), it’s harder to find a mate. One U.S. study showed that after they divorce, women have 60 percent lower odds of remarrying than men (Shafer & James, 2013).

Are remarried couples happier? The fact that one Swedish study showed women select second husbands similar in education and earnings suggests yes (Åström and others, 2013). Remarried people say they communicate better with their current spouse. Still, these reports go along with a gingerly approach to disagreements—

Whatever the answer, remarriages face unique barriers. These couples seem less committed, in the sense that they express more positive attitudes toward divorcing if they don’t get along (Whitton and others, 2013). Bringing children into the marriage involves complications that go well beyond just relating to a husband or wife (Mirecki and others, 2013).

Stepchildren are a loose cannon in remarriage, because they naturally feel angry and resentful of a stepparent for “replacing” my real mom or dad. Therefore, stepparents must tread carefully: “Be there” to give support, but do not step far into that landmine area for trouble—

339

When children live with a stepfather, do they become more attached to this person than their biological dad? One study showed length of residence trumps biology. The preference for biological fathers is attenuated the longer a child lives with a stepdad (Kalmijn, 2013). If there is open communication between children and their mothers, a happy family climate, and parents agree on child-

Yes, attachment-

Most important, these new sons and daughters can provide incredible joy: As one woman reported: “I don’t look at her as a stepdaughter because that implies they are not . . . your child . . . she’s my only child and I just accept the fact that she has another mother as well” (quoted in Whiting and others, 2007, p. 102). And a stepfather put it more bluntly: “I don’t introduce her as my stepdaughter because I didn’t step on her. I introduce her, ‘This is my daughter.’ . . . I’d go crazy if something happened to her” (quoted in Marsiglio, 2004, p. 32).

Now, let’s explore the feelings these men and women are experiencing by turning to parenthood, that second important adult role.

Tying It All Together

Question 11.1

Jared is describing marriage around the world. Which two statements can he make?

In Sweden, unmarried couples with children are far more likely to be poor.

In the United States, we no longer believe in marriage.

In Iran today, married women have far more rights than in the past.

In India, arranged marriages are in decline.

c and d

Question 11.2

Three couples are celebrating their silver anniversaries. Which relationship has followed the “classic” marital pathway?

After being extremely happy with each other during the first three years, Ted and Elaine now find that their marriage has gone steadily downhill.

Steve and Betty’s marriage has had many unpredictable ups and downs over the years.

Dave and Erika’s marital satisfaction declined, especially during the first four years, but has dramatically improved now that their children have left home.

c

Question 11.3

Describe the triangular theory to a friend and give an example of (a) romantic love, (b) consummate love, and (c) a companionate marriage. Can you think of couples who fit each category? At what stage of life are couples most likely to have companionate marriages?

According to Sternberg, by looking at three dimensions—

Question 11.4

Jennifer says, “I am trying to do exciting things with my spouse.” Mark says, “I’m passionate about focusing on my wife’s well-

Sharing mutually exciting activities cements passion. Commitment grows out of (and is embodied by) feeling devoted to a partner’s well-

Question 11.5

You are a marriage counselor. Drawing on the research with regard to (1) keeping passion alive, (2) commitment, and (3) couple communications, formulate a suggestion for “homework” to give couples who come to your office for help.

(1) Spend time together doing exciting activities you both enjoy. (2) Practice sacrificing for your mate (giving up activities you might enjoy to further your partner’s happiness). (3) Keep disagreements to the topic; never get personal when fighting; hold off from giving too much advice.

Question 11.6

Your best friend (who has children) is getting remarried. Without being excessively negative, explain frankly why her new relationship can be at risk.

Be careful! You may more quickly contemplate leaving your new spouse when you disagree. Your children are apt to feel threatened by your new relationship, and may place barriers to your getting along.

340