15.2 A Short History of Death

She contracted a summer cholera. After four days she asked to see the village priest, who came and waited to give her the last rites. “Not yet, M. le Curé, I’ll let you know when the time comes.” Two days later: “Go and tell M. le Curé to bring me Extreme Unction.”

(reported in Walter, 2003, p. 213)

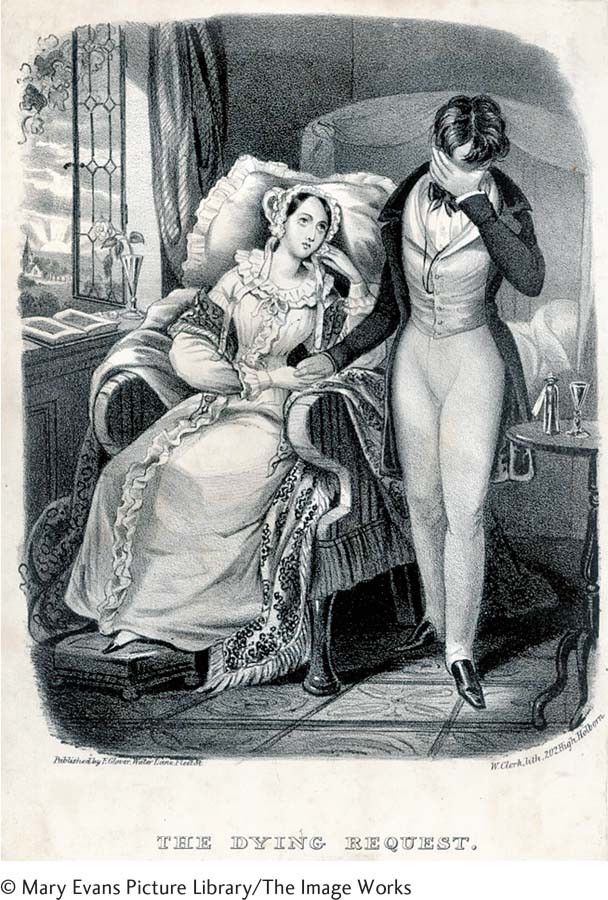

As you can see in this nineteenth-

According to the historian Philippe Ariès (1974, 1981), while life in the Middle Ages was horrid and “wild,” death was often “tame.” Famine, childbirth, and infectious disease ensured that death was an expected presence throughout the lifespan. People died, as they lived, in view of the community and were buried in the churchyard in the center of town.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, death began to move off center stage when—

As modern medicine took over, the scene of death shifted to hospitals and nursing homes. So the act of dying was disconnected from life. Because hospitals billed themselves as places of recovery, death became a symptom of scientific failure (see Risse & Balboni, 2013). When people took their last breaths, embedded in the recesses of intensive care, health-

451

In recent decades, society has shifted course. First, doctors did a total turnaround from the practice of concealing a devastating diagnosis—

Cultural Variations on a Theme

While mainstream society stresses full disclosure and actively planning for our “final act,” death attitudes differ from group to group even in the developed world. To demonstrate this point, let’s scan the practices of a culture for whom dying remains up close and personal, but death is never openly discussed: the Hmong.

The Hmong, persecuted for centuries in China and Southeast Asia, migrated to North America after the Vietnam War and number close to a million U.S. residents today. According to Hmong tradition, mentioning dying “will unlock the gate of evil spirits,” so when a person enters the terminal phase of life, no one is permitted to discuss that fact. However, when death is imminent, the family becomes intimately involved. Relatives flock around and dress the ill person in the traditional burial garment—

If, contrary to Hmong custom, the person dies in a hospital, it’s crucial that the body not be immediately sent to the morgue. The family congregates at the bedside to wail and caress the corpse for hours. Then, after a lavish four-

In this chapter, I’ll explore what dying is like in the twenty-

Tying It All Together

452

Question 15.1

Imagine that you were born in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. Which statement about your dying pathway would not be true?

You would probably have died quickly of an infectious disease.

You would have died in a hospital.

You would have seen death all around you from a young age.

You would probably have died at a relatively young age.

b

Question 15.2

If you follow the typical twenty-

slowly and erratically; an age-

Question 15.3

Ella says today we live in a death-

Amanda, because today we openly discuss death, and are making efforts to promote dignified dying.