1.4 Research Methods: The Tools of the Trade

25

Theories give us lenses for interpreting behavior. Research allows us to find the scientific truth. I already touched on the research technique designed to determine the genetic contributions to behavior. Now let’s sketch out the general research strategies that developmental scientists use.

Two Standard Research Strategies: Correlations and Experiments

What impact does poverty have on relationships, personality, or physical health? What forces cause children to model certain people? Does a particular intervention to help improve self-

In a correlational study, researchers chart the relationships between the dimensions they are interested in exploring as they naturally occur. Let’s say you want to test the hypothesis that parents who behave more lovingly have first graders with superior social skills. Your game plan is simple: Select a group of children by going to a class. Relate their interpersonal skills to the nurturing that parents provide.

Immediately, you will be faced with decisions related to choosing your participants. Are you going to explore the practices of mothers and fathers or mothers alone, confine yourself to a middle-

Then you would face your most important challenge—

With regard to the parent dimension, one possibility might be to visit parents and children and observe how they relate. This technique, called naturalistic observation, is appealing because you are seeing the behavior as it occurs in “nature,” or real life. However, this approach presents a huge practical challenge: the need to travel to each home to observe each family on many occasions. Plus, when we watch parent–

The most cost-

Now, turning to the child side of your question, one reasonable way to assess social skills would be to have teachers evaluate each student via a questionnaire: “Does this child make friends easily?”; “Does he relate to his peers in a mature way?” Or, we could ask children to rank their classmates by showing photos: “Does Calista or Cory get a smiley face?”; “Pick your three best friends.” Evaluations from expert observers, such as teachers, and even peers, are often used to assess concepts such as popularity and personality during the childhood years.

26

Table 1.5 spells out the uses, and the pluses and minuses, of these frequently used ways of measuring concepts: naturalistic observation, self-

With correlations, we may be mixing up the result with the cause. Given that parent–

child relationships are bidirectional, does loving parenting really cause superior social skills, or do socially skilled children provoke parents to act in loving ways? (“My son is such an endearing person. You want to just love him up.”) This evocative chicken- or- egg argument applies to far more than child– parent interactions. Does exercising promote health in later life, or are some older adults likely to become physically active because they are already in good health? With correlations, there may be another variable that explains the results. In view of our discussion of heritability, with regard to the social skills study, the immediate third force that comes to mind is genetics. Wouldn’t parents who are genetically blessed with superior social skills provide a more caring home environment and genetically pass down these same positive personality traits to their sons and daughters? Wouldn’t older adults who go to the gym or ski regularly also be likely to watch their diet and generally take better care of their health? Given that these other activities should naturally be associated with keeping physically fit, can we conclude that exercise alone accounts for the association we find?

| Type | Strategy | Commonly Used Ages | Pluses and Problems |

| Naturalistic observation | Observes behavior directly; codes actions, often by rating the behavior as either present or absent (either in real life or the lab) | Typically during childhood, but also used with impaired adults |

Pluses: Offers a direct, unfiltered record of behavior Problems: Very time intensive; people behave differently when watched |

| Self- |

Questionnaires in which people report on their feelings, interests, attitudes, and thoughts | Adults and older children |

Pluses: Easy to administer; quickly provides data Problems: Subject to bias if the person is reporting on undesirable activities and behaviors |

| Observer reports | Knowledgeable person such as a parent, teacher, or trained observer completes scales evaluating the person. Sometimes peers rank the children in their class | Typically during childhood; also used during adulthood if the person is mentally or physically impaired |

Pluses: Offers a structured look at the person’s behavior Problems: Observers— |

|

Table 1.5 Belsky, Experiencing The Lifespan, 4e © 2016 Worth Publishers |

|||

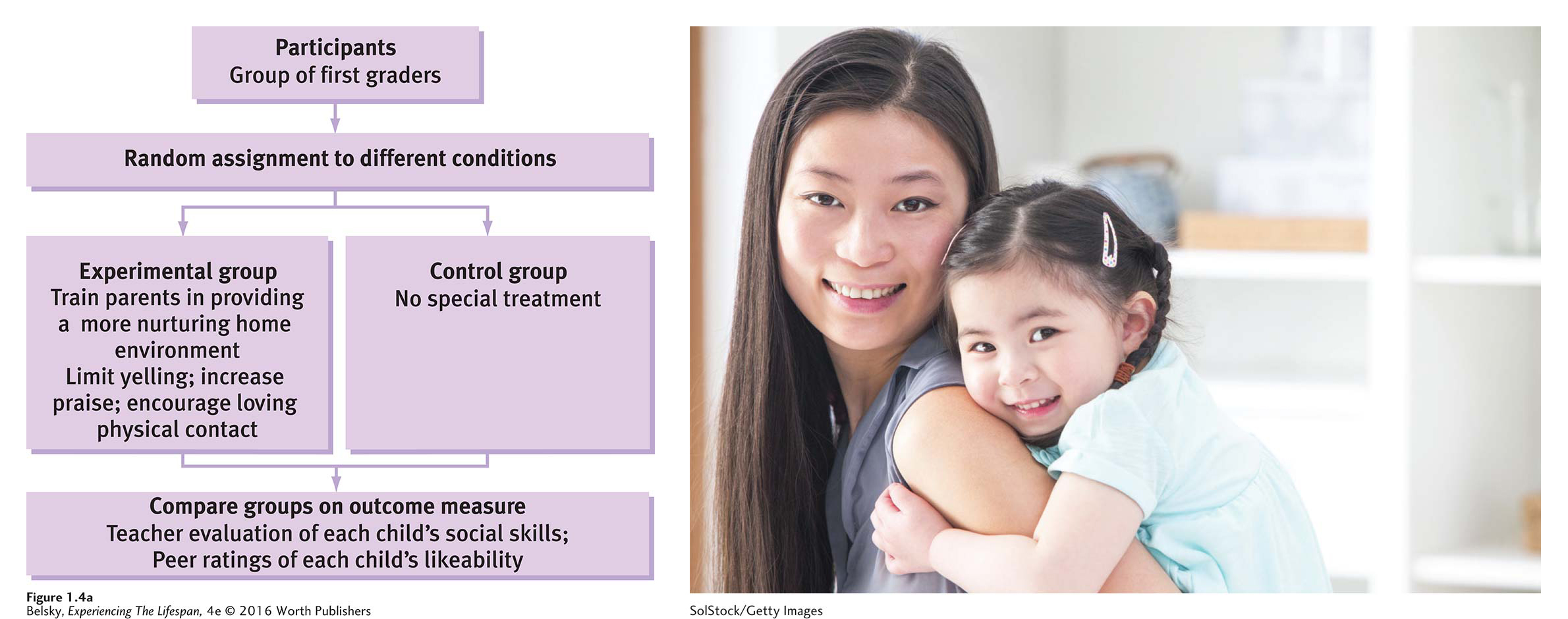

To rule out these confounding forces, the solution is to conduct a true experiment (see Figure 1.4). Researchers isolate their variable of interest by manipulating that condition (called the independent variable), and then randomly assign people to either receive that treatment or another, control intervention. If we randomly assign people to different groups (say, like tossing a coin), there can’t be any preexisting differences between our participants that would bias our results. If the group does differ in the way we predict, we have to say that our intervention caused the particular result.

The problem is that we could never assign children to different kinds of parents! If, as Figure 1.4 suggests, developmentalists trained one group of mothers to relate in more caring ways and withheld this “intervention” from another group, the researchers would run into ethical problems. Would it be fair to deprive the control group of that treatment? In the name of science, can we take the risk of doing people harm? Experiments are ideal for determining what causes behavior. But to tackle the most compelling questions about human development, we have to conduct correlational research—

Designs for Studying Development: Cross-

27

Experiments and correlational studies are standard, all-

Cross-

Because cross-

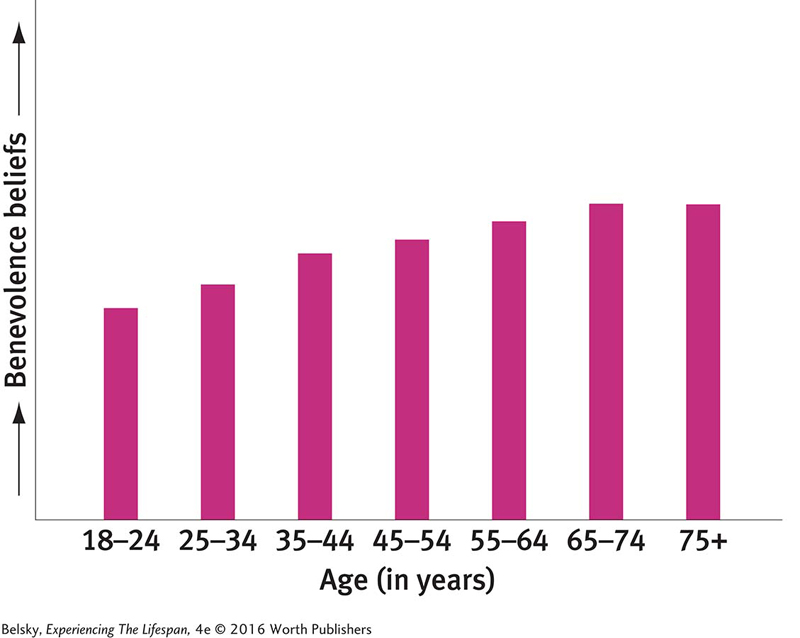

Researchers gave 2,138 U.S. adults a questionnaire measuring their beliefs in a benevolent world (Poulin & Silver, 2008). Presented with items such as “Human nature is basically good,” people ranging in age from 18 to 101 ranked each statement on a scale from “agree strongly” to “disagree.” As you scan the findings in Figure 1.5, notice that the youngest age group has the most negative perceptions about humanity. The elderly feel most optimistic about people and the world. If you are in your early twenties, does this mean you can expect to grow less cynical as you age?

28

Not necessarily. Perhaps your cohort has special reasons to feel suspicious about human motivations. After all, today the media delights in exposing the cheating and lying of authority figures, from senators to school principals. Previous cohorts of young people were never exposed to this drumbeat of messages highlighting human nature at its worst. In fact, if we conducted this same poll during the 1950s (in the Eisenhower era of Leave It to Beaver and Father Knows Best) we might find the opposite pattern: Positive feelings about human nature were highest among the young and declined with age!

The bottom line is that cross-

Cross-

Longitudinal Studies: The Gold-

In longitudinal studies, researchers typically select a group of a particular age and periodically test those people over years (the relevant word here is long). Consider the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study: An international team of researchers descended on Dunedin, a city in New Zealand, to follow more than 1,000 children born between April 1972 and March 1973, examining them at two-

The outcome has been an incredible array of findings related to personality and psychological problems. Can we predict adult emotional difficulties as early as age 3? Do chronic anxiety and depression produce cellular damage as we travel through adolescence and early adult life (Shalev and others, 2014)? As you will learn in Chapter 12, scientists have discovered that a personality trait called conscientiousness, measured during emerging adulthood, powerfully predicts following good health habits—

Moreover, because they are using cutting-

Longitudinal studies are exciting, but they have their own problems. They involve a tremendous amount of time, effort, and expense. Imagine the resources involved in planning this particular study. Think of the hassles involved in searching out the participants and getting them to return again and again to take the tests. The researchers must fly the overseas Dunedin volunteers back for each evaluation. They need to reimburse people for their time and lost wages. These logistical and financial problems become more serious the longer a study continues. For this reason, we have hundreds of studies covering infancy, childhood, or defined segments of adult life, such as the old-

29

The difficulty with getting people to return for testing leads to an important bias in itself. People who stay in longitudinal studies, particularly during adulthood, tend to be highly motivated. Think of which classmates are going to attend your high school reunion. Aren’t they apt to be the people who are successful, versus those who have made a mess of their lives? Participants in longitudinal research are typically elite, better than average groups. While they offer us unparalleled information, these gold-

Critiquing the Research

So to summarize, when you are scanning the findings in our field, keep these concerns in mind:

Consider the study’s participants. How were they selected? Ask yourself, “Can I generalize from this particular group to the wider world?”

Examine the study’s measures. Are they accurate? What biases might they have?

In looking at the many correlational studies in this book, be attuned to the fact that their findings might be due to other forces. What competing interpretations can you come up with to explain this researcher’s results?

With cross-

sectional findings, beware of making assumptions that this is the way people really change with age. Look for longitudinal studies and welcome their insights. However, understand that—

especially during adult life— these investigations are probably tracing the lives of the best and brightest people rather than the average adult.

Emerging Research Trends

Developmental scientists are attuned to these issues. In conducting correlational studies, they typically try to control for other influences that might explain their findings. They are apt to use several measures, such as teacher ratings, formal questionnaires, and peer input, as well as direct observations, to make sure they are measuring their concepts accurately. As you will see throughout this book, current developmental research has an international flavor, with researchers from nations as different as Iran and Ireland or China and Cameroon offering country-

Quantitative research techniques—

Some Concluding Introductory Thoughts

30

This discussion brings me back to the letter on page 2 and my promise to let you in on my other agendas in writing this text. Because I want to teach you to critically evaluate research, in the following pages I’ll be analyzing individual studies and—

This book is designed to be read like a story with each chapter building on concepts and terms mentioned in the previous ones. It’s planned to emphasize how our insights about earlier life stages relate to older ages. I will be discussing three major aspects of development—

While I want you to share my excitement in the research, please don’t read this book as “the final word.” Science—

Now, beginning with prenatal development and infancy (Chapters 2, 3, and 4); then moving on to childhood (Chapters 5, 6, and 7); adolescence (Chapters 8 and 9); early and middle adulthood (Chapters 10, 11, and 12); later life (Chapters 13 and 14); and, finally, that last milestone, death (Chapter 15), welcome to the lifespan and to the rest of this book!

Tying It All Together

Question 1.11

Four developmentalists are studying whether eating excessive sugar has detrimental effects on the body and mind: Alicia relates the amount of sugar elementary schoolers eat at breakfast to aggression, by going to a playground and counting the frequency of hitting on selected days. Betty randomly assigns students in a high school class into two groups, tells one group to eat a healthy diet and another to eat candy bars, and compares their grades on tests. Calista measures the sugar consumption of teens and then retests them periodically into their fifties. David constructs a questionnaire exploring sugar consumption and gives it to adults of different ages. For each question below, link the appropriate person’s name to the correct study.

Who is conducting a cross-

sectional study? Who is using naturalistic observation?

Who is conducting a correlational study?

Who can prove that eating a lot of sugar causes problems—

but is doing an unethical study? Who is going to have a huge problem with dropouts?

Who can tell you that if you are a sugar junkie in your twenties, you might still be eating an incredible amount of sugar (compared to everyone else) as you age?

a. David; b. Alicia; c. Alicia; d. Betty; e. Calista; f. David

Question 1.12

Plan a longitudinal study to test a developmental science question. Describe how you would select your participants, how your study would proceed, what measures you would use, and what problems and biases your study would have.

After coming up with your hypothesis, you would need to adequately measure your concepts—