2.6 Birth

During the last weeks of pregnancy, the fetus’s head drops lower into the uterus. On their weekly visits to the health-

I am 39 weeks and desperate for some sign that labor is near, but so far NOTHING—

What sets off labor? One hypothesis is that the trigger is a hormonal signal that the fetus sends to the mother’s brain. Once it’s officially under way, labor proceeds through three stages.

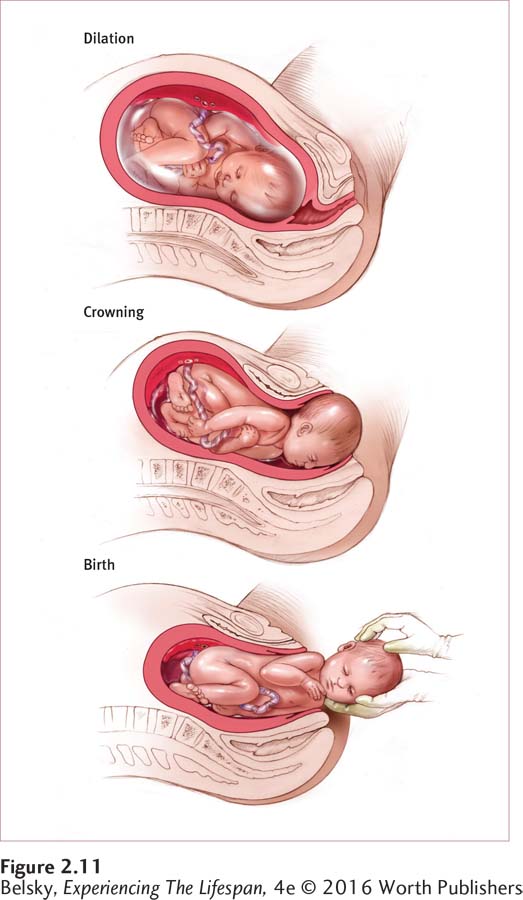

Stage 1: Dilation and Effacement

This first stage of labor is the most arduous. The thick cervix, which has held in the expanding fetus for so long, has finished its job. Now it must efface, or thin out, and dilate, or widen from a tiny gap about the size of a dime to the width of a coffee mug or a medium-

The contractions start out slowly, perhaps 20 to 30 minutes apart. They become more frequent and painful as the cervix more rapidly opens up. Sweating, nausea, and intense pain can accompany the final phase—

Stage 2: Birth

The fetus descends through the uterus and enters the vagina, or birth canal. Then, as the baby’s scalp appears (an event called crowning), parents get their first exciting glimpse of this new life. The shoulders rotate; the baby slowly slithers out, to be captured and cradled as it enters the world. The prenatal journey has ended; the journey of life is about to begin.

Stage 3: The Expulsion of the Placenta

In the ecstasy of the birth, the final event is almost unnoticed. The placenta and other supporting structures must be pushed out. Fully expelling these materials is essential to avoid infection and to help the uterus return to its pre-

Threats at Birth

61

Just as with pregnancy, a variety of missteps may happen during this landmark passage into life: problems with the contraction mechanism; the inability of the cervix to fully dilate; deviations from the normal head-

Birth Options, Past and Present

For most of human history, pregnancy was a grim nine-

Women had only one another or lay midwives to rely on during this frightening time. So birth was a social event. Friends and relatives flocked around, perhaps traveling miles to offer comfort when the woman’s due date drew near. Doctors were of little help, because they could not view the female anatomy directly. In fact, due to their clumsiness (using primitive forceps to yank the baby out) and their tendency to spread childbed fever by failing to wash their hands, eighteenth-

Techniques gradually improved toward the end of the nineteenth century, but few wealthy women dared enter hospitals to deliver, as these institutions were hotbeds of contagious disease. Then, with the early-

This watershed medical victory was accompanied by discontent. The natural process of birth had become an impersonal event. Women protested the assembly-

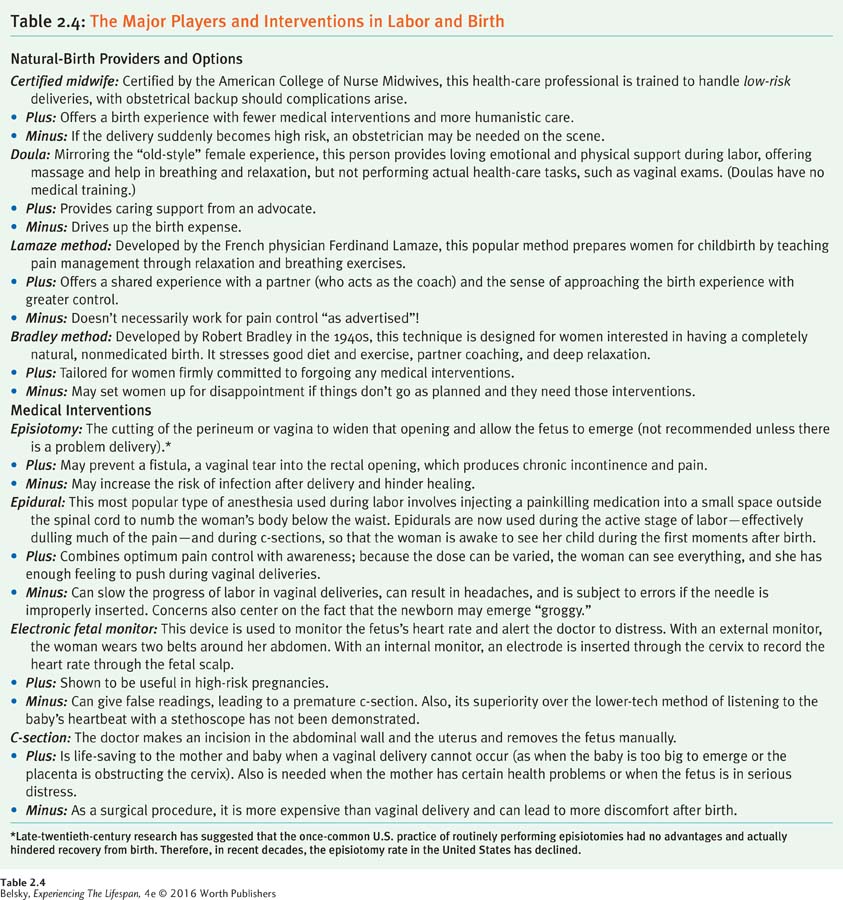

Natural Childbirth

Natural childbirth, a vague label for returning the birth experience to its “true” natural state, is now embedded in the labor and birth choices available to women today. To avoid the hospital experience, some women choose to deliver in homelike birthing centers. They may use certified midwives rather than doctors, and draw on the help of a doula, a nonmedical pregnancy and labor coach. Women who are committed to the most natural experience may give birth in their own homes. (Table 2.4 on page 62 describes some natural birth options, as well as some commonly used medical procedures.)

At the medical end of the spectrum, as Table 2.4 shows, lies the arsenal of physician interventions designed to promote a less painful and safer birth. Let’s now pause for a minute to look at the last procedure in the table: the cesarean section.

62

The Cesarean Section

A cesarean section (or c-

Some c-

63

Most c-

“I sort of feel like I failed in the birthing arena,” said one Australian woman . . . “Logically I knew that the c-

(quoted in Malacrida & Boulton, 2014, p. 18)

Finally, while affluent women may bemoan their c-

Tying It All Together

Question 2.19

Melissa says that her contractions are coming every 10 minutes now. Sonia has just seen her baby’s scalp emerge. In which stages of labor are Melissa and Sonia?

Melissa is in stage 1, effacement and dilation of the cervix. Sonia is in stage 2, birth.

Question 2.20

To a friend interested in having the most natural birth possible, spell out some of these options.

“You might want to forgo any labor medications, and/or give birth in a birthing center under a midwife’s (and doula’s) care. Look into new options such as water births, and, if you are especially daring, consider giving birth at home.”

Question 2.21

C-

C-