2.7 The Newborn

Now that we have examined how the baby arrives in the world, let’s focus on that tiny arrival. What happens after the baby is born? What dangers do babies face after birth?

Tools of Discovery: Testing Newborns

The first step after the newborn enters the world is to evaluate its health in the delivery room with a checklist called the Apgar scale. The child’s heart rate, muscle tone, respiration, reflex response, and color are rated on a scale of 0 to 2 at one minute and then again at five minutes after birth. Newborns with five-

Threats to Development Just After Birth

64

After their babies have been checked out medically, most mothers and fathers eagerly take their robust, full-

Born Too Small and Too Soon

In 2010, about 15 million babies were born preterm, or premature—

Earlier in this chapter, I highlighted smoking and maternal stress as risk factors for going into labor early and/or having a low birth weight baby. But, uncontrollable influences—

You might assume that prematurity has declined in tandem with our pregnancy medical advances. Not so! Ironically, the same cutting-

Many early arrivals are fine. The vulnerable newborns are the 1.4 percent classified as very low birth weight, babies weighing less than 3 1/4 pounds. When these infants are delivered, often very prematurely, they are immediately rushed to a major medical center to enter a special hospital unit for frail newborns—

At 24 weeks my water broke, and I was put in the hospital and given drugs. I hung on, and then, at week 26, gave birth. Peter was sent by ambulance to Children’s Hospital. When I first saw my son, he had needles in every point of his body and was wrapped in plastic to keep his skin from drying out. Peter’s intestines had a hole in them, and the doctor had to perform an emergency operation. But Peter made it! . . . Now it’s four months later, and my husband and I are about to bring our miracle baby home.

Peter was lucky. He escaped the fate of the more than 1 million babies who die each year as a consequence of being very premature (Chang and others, 2013). Is this survival story purchased at the price of a life of pain? Enduring health problems are a serious risk with newborns such as Peter, born too soon and excessively small. Study after study suggests low birth weight can compromise brain development (Rose and others, 2014; Yang and others, 2014). It may impair preschoolers’ growth and motor abilities (Raz and others, 2014). It can limit intellectual and social skills throughout childhood (Murray and others, 2014) and the adolescent years (Healy and others, 2013; Yang and others, 2014)—in addition, as you know, to possibly promoting overweight and early age-

When a child is born at the cusp of viability—

Even when they do have disabilities, these tiny babies can have a full life. Listen to my former student Marcia, whose 15-

The Unthinkable: Infant Mortality

65

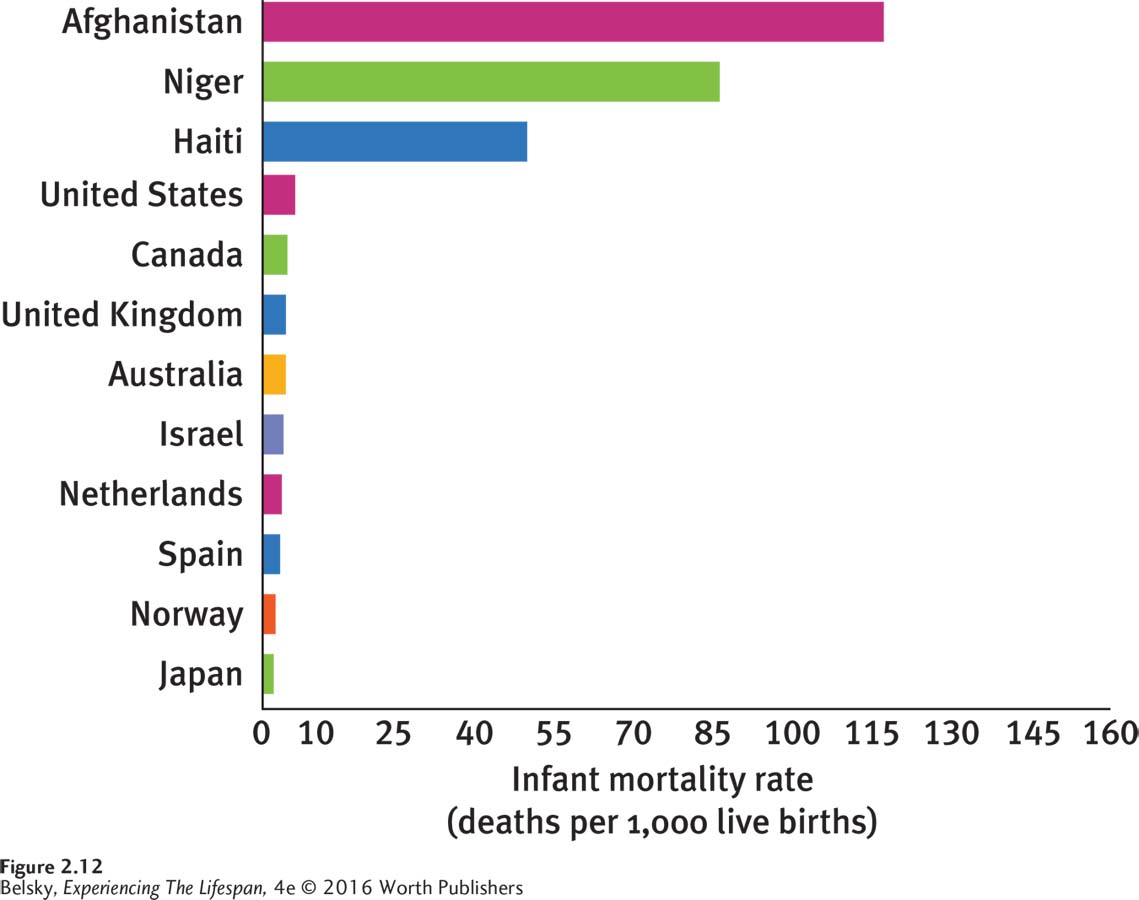

In the developed world, prematurity is the primary cause of infant mortality—the term for deaths occurring within the first year of life. The good news is that in affluent nations, infant mortality is at an historic low (see Figure 2.12). The bad news is the dismal standing of the United States compared to many other industrialized countries. Why does the United States rank a humiliating forty-

Experiencing the Lifespan: Marcia’s Story

The service elevator at Peck Hall takes forever to get there, then moves in extra-

My goal is to be at least five minutes early so I don’t disrupt everything as I move the chair, back and forth, back and forth, to be positioned right in front. Because my bad eye wanders to the side, you may not think I can read the board. That’s no problem, although it takes me weeks to get through a chapter in your book! The CP [cerebral palsy], as you know, affects my vocal cords, making it hard to get a sentence out. But I won’t be ashamed. I am determined to participate in class. I have my note-

I usually can take about two courses each semester—

I’m not sure exactly what week I was born, but it wasn’t really all that early; maybe two months at the most. My problem was being incredibly small. They think my mom might have gotten an infection that made me born less than one pound. The doctors were sure I’d never make it. But I proved everyone wrong. Once I got out of the ICU and, at about eight months, went into convulsions, and then had a stroke, everyone thought that would be the end again. They were wrong. I want to keep proving them wrong as long as I live.

I’ve had tons of physical therapy, and a few surgeries; so I can get up from a chair and walk around a room. But it took me until about age five to begin to speak or take my first step. The worst time of my life was elementary school—

In my future? I’d love to get married and adopt a kid. OK, I know that’s going to be hard. Because of my speech problem, I know you’re thinking it’s going to be hard to be a counselor, too. But I’m determined to keep trying, and take every day as a blessing. Life is very special. I’ve always been living on borrowed time.

66

The socioeconomic link to pregnancy and birth problems is particularly troubling. In every affluent nation—

A Few Final Thoughts on Biological Determinism and Biological Parents

But I also can’t leave you with the downbeat impression that what happens during pregnancy is destiny. Yes, researchers now believe events “in-

Now that we are on the topic of biology, I feel compelled to highlight a personal point, as an adoptive mom. In this chapter, you learned about the feelings of attachment (or mother-

The next two chapters turn directly to the joys of babyhood, as we catch up with Kim and her daughter Elissa, and track development during the first two years of life.

Tying It All Together

Question 2.22

Baby David gets a two-

Baby David is in excellent health.

Question 2.23

Rates of premature births have risen/declined due to ART and low birth weight always causes serious problems/can produce problems/has no effects on later development.

Rates of premature births have risen due to ART; and low birth weight can produce problems in later development.

Question 2.24

Bill says, “Pregnancy and birth are very safe today.” George says, “Hey, you are very wrong!” Who is right?

Bill, because worldwide maternal mortality is now very low.

George, because birth is still unsafe around the world.

Both are partly correct: Birth is typically very safe in the developed world, but maternal and infant mortality remains unacceptably high in the poorest regions of the globe.

c. While birth is very safe in the developed world, maternal and infant mortality remain serious problems in the least-

Question 2.25

Sally brags about the U.S. infant mortality rate, while Samantha is horrified by it. First make Sally’s case and then Samantha’s, referring to the chapter points.

Sally: The United States—

Question 2.26

You want to set up a program to reduce prematurity and neonatal mortality among low-

You can come up with your own suggestions. Here are a few of mine: Increase the number of nurse-