4.1 Attachment: The Basic Life Bond

108

Perhaps you remember being intensely in love. You may be in that wonderful state right now. You cannot stop fantasizing about your significant other. Your moves blend with your partner’s. You connect in a unique way. Knowing that this person is there gives you confidence. You can conquer the world. You feel uncomfortable when you are separated. Your world depends on having your lover close. Now you know how Elissa feels about her mother and the powerful emotions that flow from Kim to her child.

Setting the Context: How Developmentalists (Slowly) Got Attached to Attachment

During much of the twentieth century, U.S. psychologists seemed indifferent to these feelings. At a time when psychology was dominated by behaviorism, studying love seemed unscientific. Behaviorists minimized our need for attachment, suggesting that babies wanted to be close to their mothers because this “maternal reinforcing stimulus” provided food. Worse yet, one famous early behaviorist named John Watson seemed hostile to attachment when he crusaded against the dangers of “too much” mother love:

When I hear a mother say “bless its little heart” when it falls down, I . . . have to walk a block or two to let off steam. . . . Can’t she train herself to substitute a kindly word . . . for . . . the coddling? . . . Can’t she learn to keep away from the child a large part of the day? [And then he made this memorable statement:] . . . I sometimes wish that we could live in a community of homes [where] . . . we could have the babies fed and bathed each week by a different nurse. (!)

(Watson, 1928/1972, pp. 82–

European psychoanalysts felt differently. They discovered that attachment was far from dangerous. It was crucial to infant life.

Consider a heart-

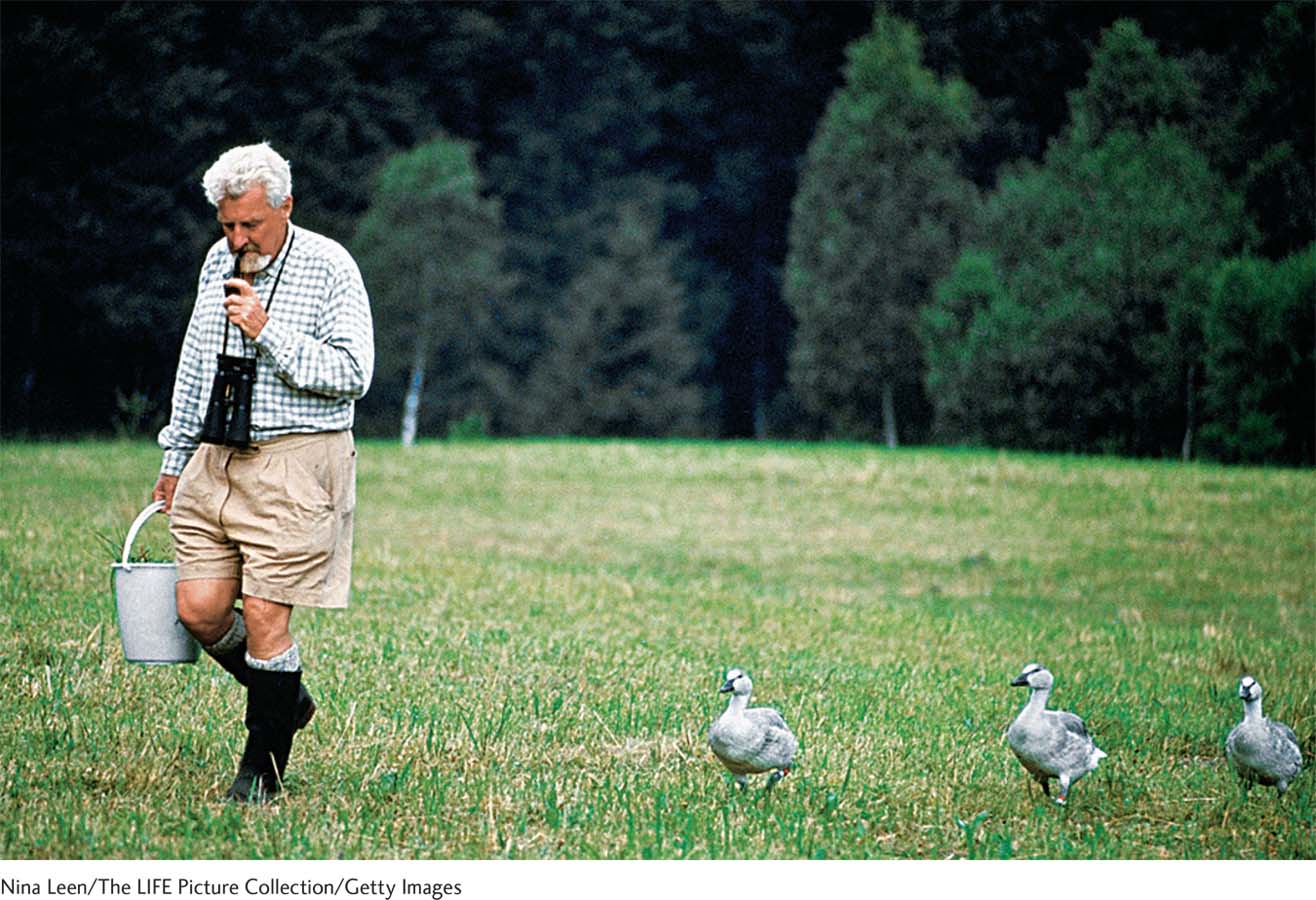

Now consider that ethologists—

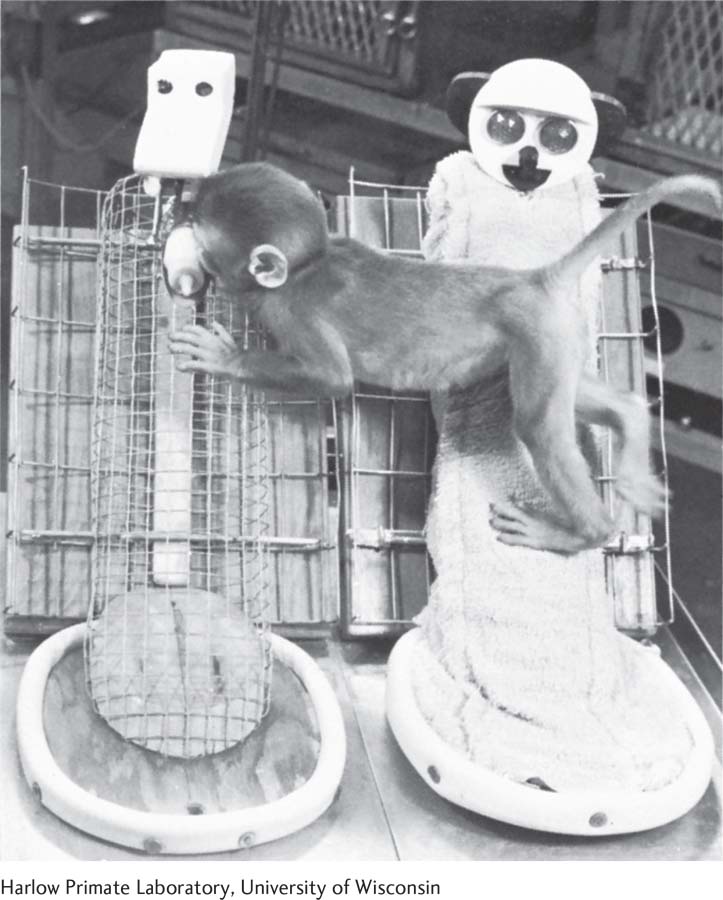

However, it took a rebellious psychologist named Harry Harlow, who studied monkeys, to convince U.S. psychologists that the behaviorist meal-

109

Moreover, there were serious psychological consequences for the monkeys raised without their moms. The animals couldn’t have sex. They were frightened of their peers. After being artificially inseminated and giving birth, the “motherless mothers” were uncaring, abusive parents. One mauled her baby so badly that it later died (Harlow and others, 1966; Harlow, C. M., 1986).

Then, in the late 1960s, John Bowlby put the evidence together—

Exploring the Attachment Response

Bowlby (1969, 1973) made his case for the crucial importance of attachment based on evolutionary theory. He believed that, as with other species, human beings have a critical period when the attachment response “comes out.” As with Lorenz’s ducks, attachment is built into our genetic code to allow us to survive. Although the attachment response is programmed to emerge during our first years of life, proximity-

Bowlby believed that threats to survival come in two categories. They may be activated by our internal state. When a child clings only to her mom, you know she must be tired. When you go to the hospital, you make sure that your family is close. You immediately text your “significant other” when you have a fever or the flu.

They may be evoked by dangers in the external world. During childhood, it’s a huge dog that causes us to run anxiously into our parent’s arms. As adults, it’s a professor’s nasty comment or a humiliating experience at work that provokes a frantic call to our primary attachment figure, be it our spouse, our father, or our best friend.

Although we all need to touch base with our significant others when we feel threatened, adults and older children can be separated from their attachment figures for some time. During infancy and early childhood, simply being physically apart causes distress. Now, let’s trace step-

Attachment Milestones

According to Bowlby, during their first three months of life, babies are in the preattachment phase. Remember that during this reflex-

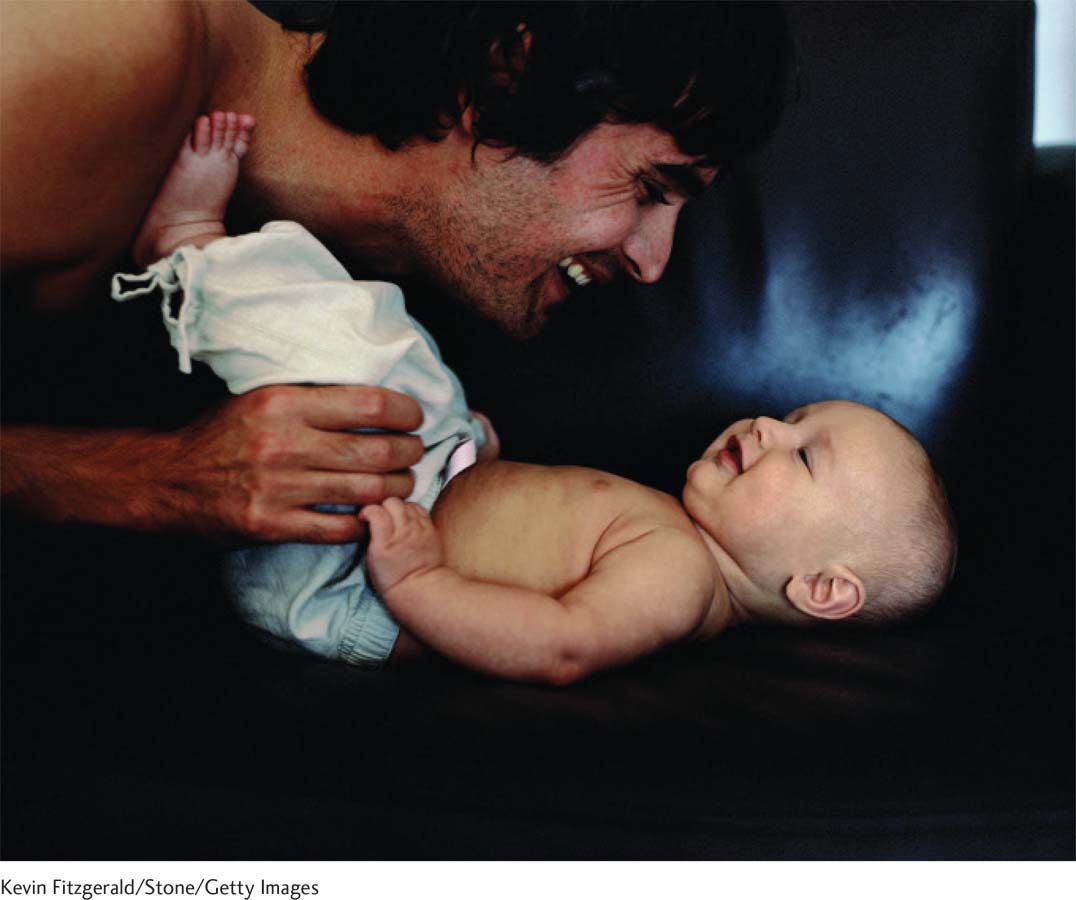

Still, a baby’s eagerly awaited first smile can be an incredible experience if you are a parent. Suddenly, your relationship with your child shifts to a different plane. Now, I have a confession to make: During my first 2 months as a new mother, I was worried, as I did not feel anything for this beautiful child I had waited so long to adopt. I date Thomas’s first endearing smile as the defining event in my lifelong attachment romance.

110

At roughly 4 months of age, infants enter a transitional period, called attachment in the making. At this time, Piaget’s environment-

By around 7 or 8 months of age, this changes. At this age, as you saw in Chapter 3, babies are hunting for hidden objects—

Separation anxiety signals this milestone. When your baby is about 7 or 8 months old, she suddenly gets uncomfortable when you leave the room. Then, stranger anxiety appears. Your child gets agitated when any unfamiliar person picks her up. So, as children travel toward their first birthday, the universal friendliness of early infancy is gone. While they may still joyously gurgle at the world from their caregiver’s arms, it’s normal for babies to forbid any “stranger”—a nice day-

Between ages 1 and 2, the distress reaches a peak. A toddler clings and cries when mom or dad makes a motion to leave. It’s as if an invisible string connects the caregiver and the child. In one classic study at a park, 1-

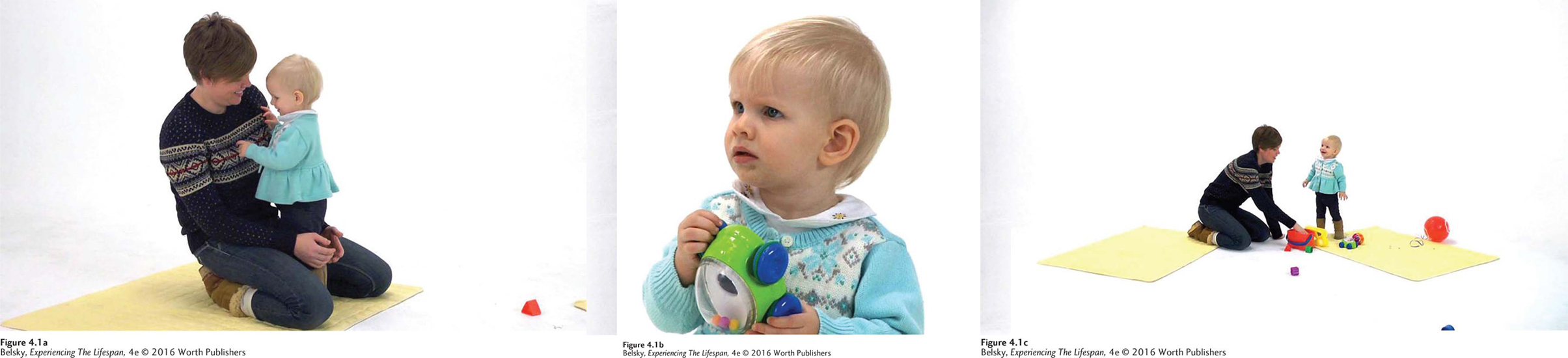

To see these changes, pick up a young baby (such as a 4-

Social referencing is the term developmentalists use to describe this checking-

Social referencing is not only the glue that permits babies to safely venture into the world; we depend on this core social cognitive skill (“She is looking upset. I’d better not do that!”) to pace our behavior from age 1 to 101. When does the infant attachment response—

The bottom-

Do children differ in the way they express this priceless sense of connection? And if so, what might these differences mean about the quality of the infant–

Attachment Styles

111

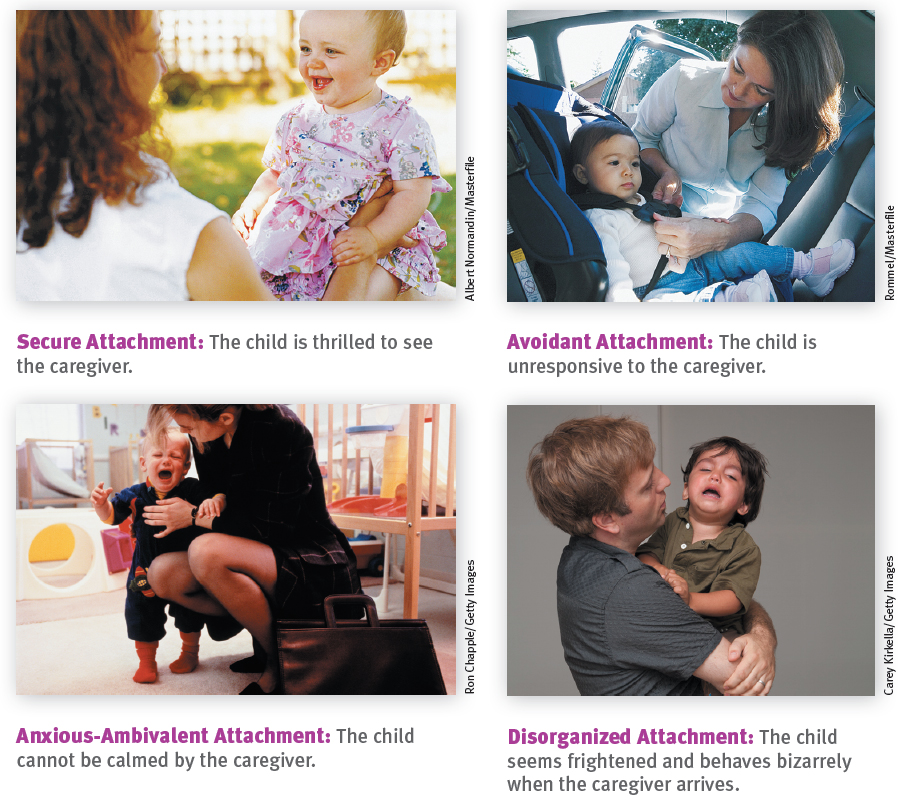

Mary Ainsworth answered these questions by devising a classic test of attachment—

The Strange Situation procedure begins when a mother and a 1-

Securely attached children use their mother as a secure base, or anchor, to explore the toys. When she leaves, they may or may not become highly distressed. Most important, when she returns, their eyes light up with joy. Their close relationship is apparent in the way they run and melt into their mothers’ arms. Insecurely attached children react in one of three ways:

Infants classified as avoidant seem excessively detached. They rarely show separation anxiety or much emotion—

positive or negative— when their primary attachment figure returns. They seem wooden, disengaged, without much feeling at all. Babies with an anxious-

ambivalent attachment are at the opposite end of the spectrum— clingy, nervous, too frightened to explore the toys. Terribly distressed by their mother’s departure, these infants may show contradictory emotions when she returns— clinging and then striking out in anger. Often, they are inconsolable, unable to be comforted when their attachment figure comes back. Children showing a disorganized attachment behave in a genuinely bizarre manner. They freeze, run around erratically, or even look frightened when the caregiver returns.

Developmentalists point out that the insecure attachments illustrated in my summary in Figures 4.2a, 4.2b, 4.2c and 4.2d on page 112 do not show a weakness in the underlying connection. Avoidant infants are just as bonded to their caregivers as babies ranked secure. Anxious-

112

The Attachment Dance

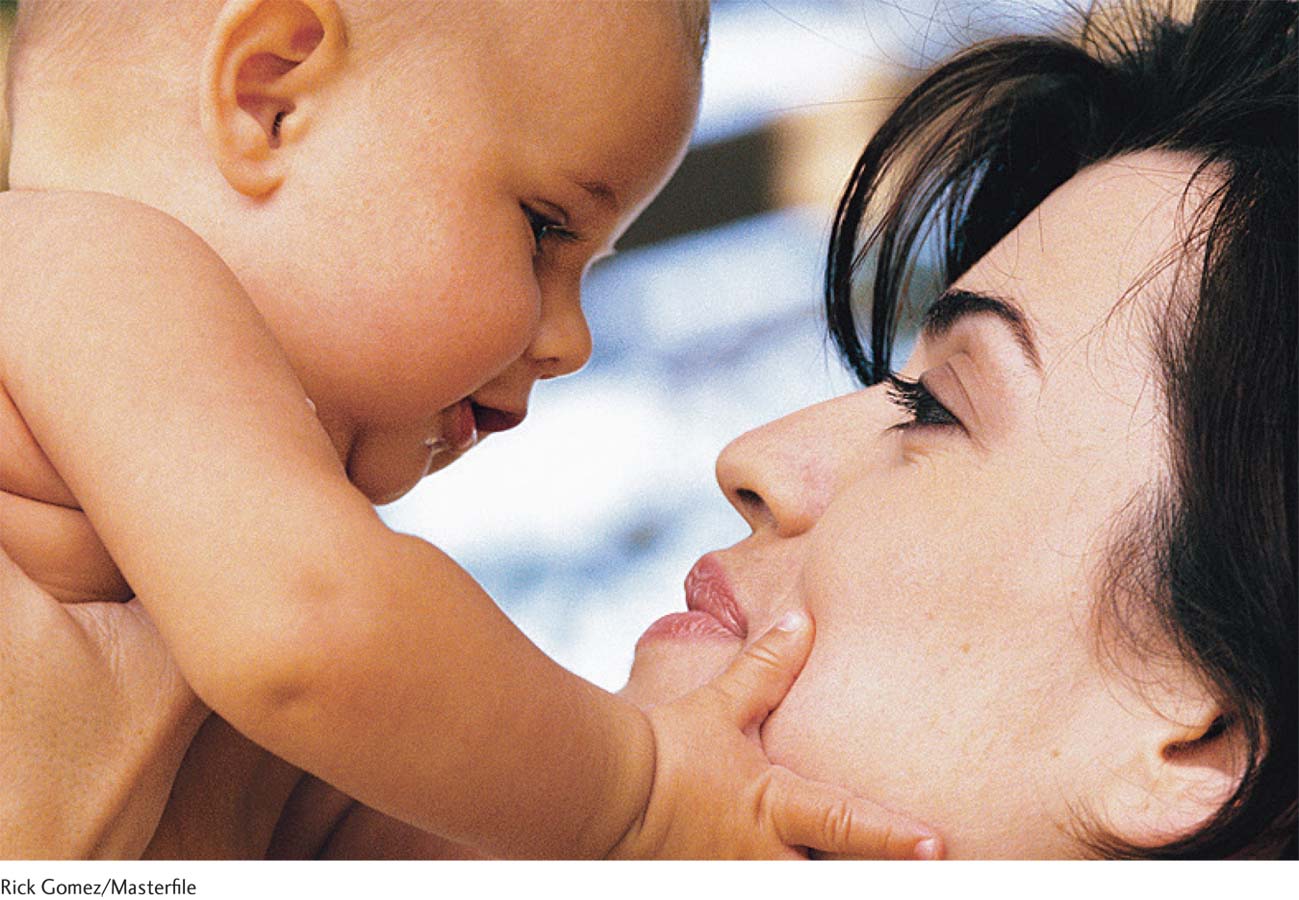

Look at a baby and a caregiver and it is almost as if you are seeing a dance. The partners are alert to each other’s signals. They know when to come on stronger and when to back off. They are absorbed and captivated, oblivious to the world. This blissful synchrony, or sense of being totally emotionally in tune, is what makes the infant–

The Caregiver

Decades of studies suggest that the answer is yes. Sensitive caregivers tend to have babies who are securely attached. Parents who misread their baby’s signals or are rejecting, disengaged, or depressed are more apt to have infants ranked insecure (see Behrens, Parker, & Haltigan, 2011 and Zeanah, Berlin, & Boris, 2011 for a review).

Still, because these are correlations, if we find that securely attached parents have open, loving children or that distant moms and dads have avoidant babies, couldn’t these people be passing these styles of responding down in their genes? Furthermore, by blaming children’s attachment issues on parents, aren’t we neglecting the fact that there are two partners in the dance?

The Child

Listen to any mother comparing her babies (“Sara was fussy; Matthew is easier to soothe”) and you will realize that not all infants are born with the same dancing talent. Babies differ in temperament—characteristic, inborn behavioral styles of approaching the world.

113

In a pioneering study, developmentalists classified a group of middle-

Everything bothers my 5-

Now, consider the stressful experiences a baby must go through during the Strange Situation. Do you see why some developmentalists have argued that biologically based differences in temperamental “reactivity”—not the quality of a mother’s caregiving—

Does a baby’s biology (nature) or poor caregiving (nurture) produce insecure attachments? As you might imagine—

But with biologically vulnerable infants, there is a limit to what the most sensitive parent can achieve. Suppose a child was extremely premature or autistic, or had some serious disease. Would it be fair to label the baby’s attachment issues as the caregiver’s fault?

Moreover, because “it takes two to tango” (that is, the dance is bidirectional), a child’s temperament affects the parent’s sensitivity, too. To use an analogy from real-

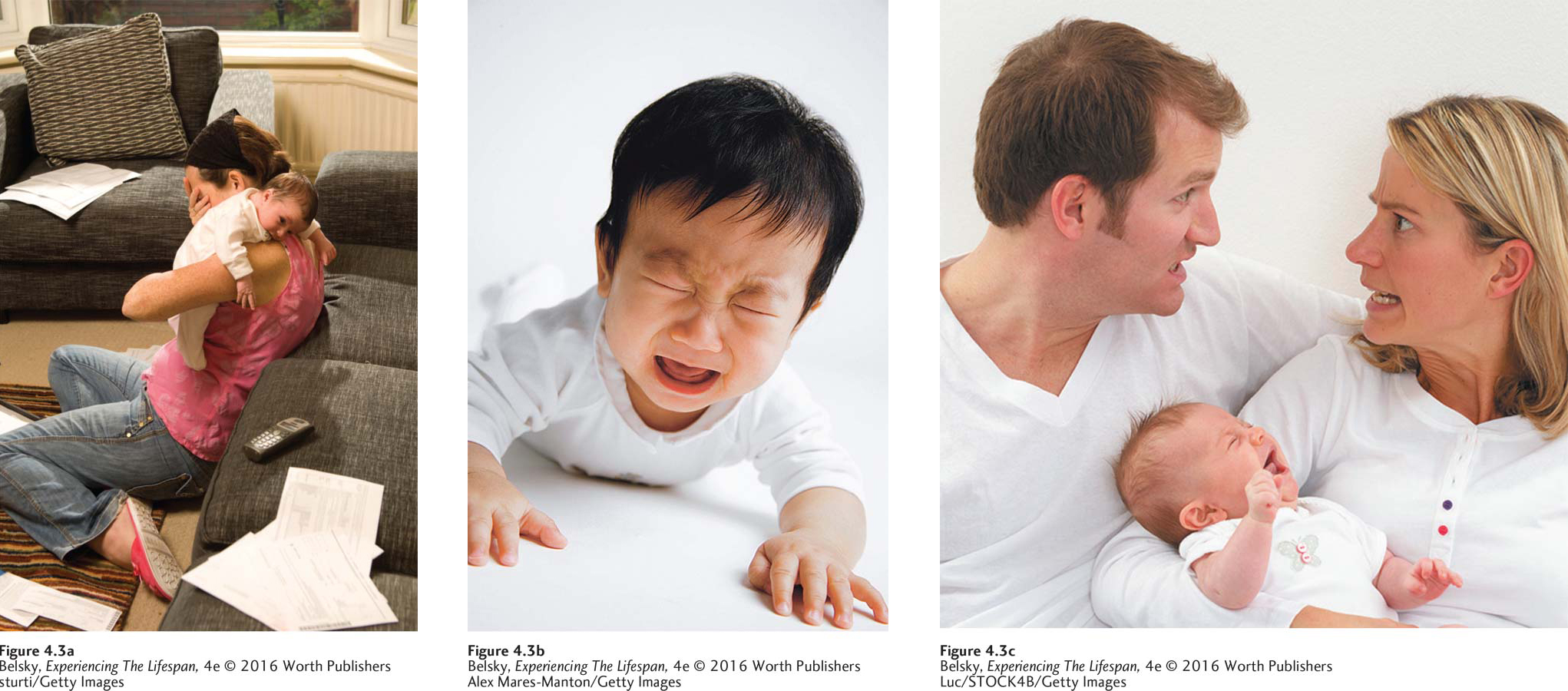

The Caregiver’s Other Attachments

And, to continue the analogy, it takes more than two to tango. Just as a woman’s attitudes about being pregnant depend on feeling supported by the wider world (recall Chapter 2), it is difficult to be a sensitive caregiver if your other attachment relationships are not working out. When mothers (and fathers) are unhappily married, or don’t dance well with each other, their babies are more likely to be rated as insecurely attached (Cowan, Cowan, & Mehta, 2009; Moss and others, 2005).

Figure 4.3 below—

Is Infant Attachment Universal?

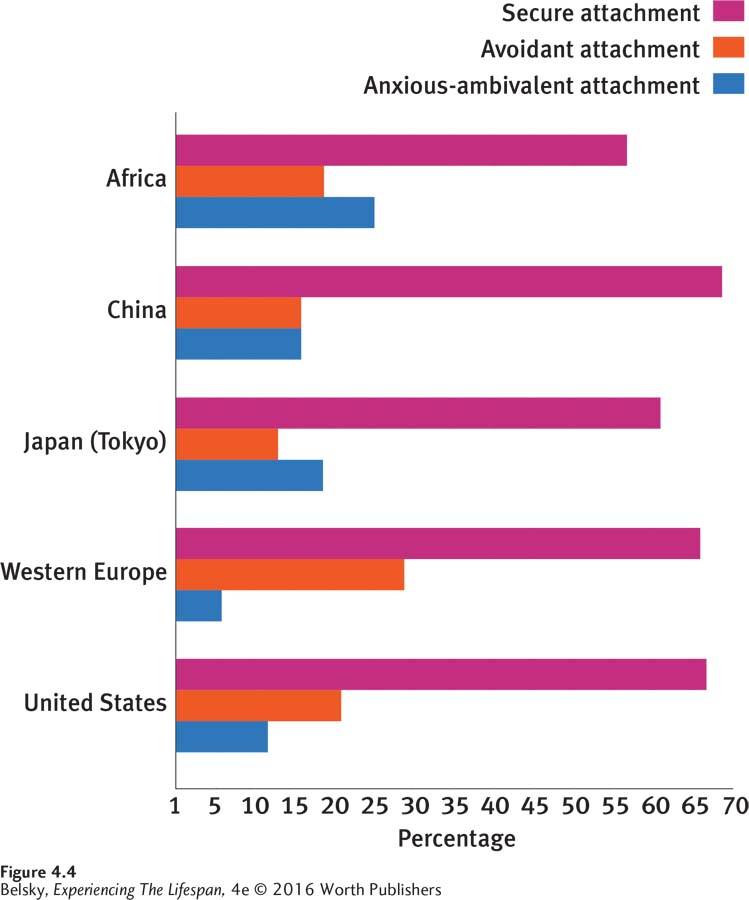

From Chicago to Capetown, from Naples to New York, Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s ideas about attachment get high marks (van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999). Babies around the world get attached to a primary caregiver at roughly the same age. As Figure 4.4 on page 114 shows, the percentages of infants ranked secure in different countries are remarkably similar—

114

The most amazing validation of attachment’s universal quality comes from the Efé, a communal hunter-

So far you might be thinking that during the phase of clear-

Interestingly, when babies are upset, they run to their primary caregiver—

In a heartening longitudinal study, 15-

Does Infant Attachment Predict Later Relationships and Mental Health?

115

Bowlby’s core argument, in his working-

Again, decades of research support Bowlby’s prediction. Securely attached babies tend to be more socially competent and popular (McElwain and others, 2011; Rispoli and others, 2013). Insecure attachment foreshadows anxiety (Madigan and others, 2013), trouble managing one’s emotions, and interpersonal problems, later on (Pasco Fearon and others, 2010; Kochanska and others, 2010; von der Lippe and others, 2010).

Interestingly, the most potent predictor of problems is the disorganized attachment style. This erratic, confused infant response is a risk factor for “acting-

However, the operative word here is “risk factor.” Landmark longitudinal studies measuring attachment at age 1 and tracking babies into their adult years suggest that, while there is “moderate continuity,” attachments do change (Grossmann and others, 2005; Simpson and others, 2007; Sroufe and others, 2005; Pinquart and others, 2013).

One obvious cause relates to the environment. Sensitive, loving relationships—

Consider a boy named Tony, in one major infant-

It seems logical that life experiences might change our attachment relationships for the better or the worse. But research—

Exploring the Genetics of Attachment Stability and Change

Oxytocin qualifies as the attachment hormone, as this substance elicits bonding, caregiving, and nurturing in mammals and in our own species (Rilling, 2013). When researchers in the infant-

116

The bottom-

Hot in Developmental Science: Experiencing Early Life’s Worst Deprivation

“When I . . . walked into the . . . building (in 1990),” said a British school teacher . . . “what I saw was beyond belief . . . babies lay three and four to a bed, given no attention. . . . There were no medicines or washing facilities, . . . physical and sexual abuse were rife . . . I particularly remember . . . the basement. There were kids there who hadn’t seen natural light in years.”

(McGeown, 2005, para. 4)

This scene was not from some horror movie. It was real. This woman had entered a Romanian orphanage, the bitter legacy of the dictator Ceausescu’s decision to forbid contraception, which caused a flood of unwanted babies that destitute parents dumped on the state.

When the “Iron Curtain” fell and revealed these grisly Eastern European scenes, British and American families rushed in to adopt these children. But then parents began to report distressing symptoms—

Which institution-

First, babies adopted from the most intensely depriving institutions—

What are these children’s symptoms? A classic sign of this “institutionalization syndrome” is the indiscriminate friendliness I just described (this is called reactive attachment disorder). Another is deficits in attention (McLaughlin and others, 2010; Wiik and others, 2011). EEG studies suggest the reason for this impaired focusing ability is that lack of stimulation delays the maturation of the brain (McLaughlin and others, 2010).

As they tracked babies subjected to these unfortunate “natural experiments,” scientists discovered that institutionalized boys are more vulnerable than girls to having enduring attachment problems (McLaughlin and others, 2012). While a massive catch-

Wrapping Up Attachment

117

To summarize, infancy is a special zone of sensitivity for forming relationships. The attachment response that unfolds during our first years of life lays down the foundation for healthy development in a variety of life realms. Still, attachment capacities (and human brains) are malleable, and negative paths can be altered provided the deprivation is not too profound and the wider world provides special help. How does the wider world affect development during infancy and beyond? To explore this question, let’s look at two crucial infant wider-

Tying It All Together

Question 4.1

List an example of “proximity-

Your responses will differ, but any example you give, such as “I called Mom when that terrible thing happened at work,” should show that in a stressful situation your immediate impulse was to contact your attachment figure.

Question 4.2

Muriel is 1 month old, Janine is 5 months old, Ted is 1 year old, and Tania is age 3. List each child’s phase of attachment.

Muriel = preattachment; Janine = attachment in the making; Ted = clear-

Question 4.3

Match term to the correct definition: (1) social referencing; (2) working model; (3) synchrony; (4) Strange Situation.

A researcher measures a child’s attachment at age 1 in a series of separations and reunions with the mother.

A toddler keeps looking back at the parent while exploring at a playground.

An elementary school child keeps an image of her parent in mind to calm herself when she gets on the school bus in the morning.

A mother and baby relate to each other as if they are totally in tune.

(1) b; (2) c; (3) d; (4) a

Question 4.4

Your cousin is the primary caregiver of her 1-

The child has an avoidant attachment.

Question 4.5

Manuel is arguing for the validity of attachment theory as spelled out by Bowlby and Ainsworth. Manuel should say (pick one, neither, or both): Infants around the world get attached to a primary caregiver at roughly the same age/a child’s attachment status as of age 1 never changes.

Manuel should say: Infants around the world get attached to a primary caregiver at roughly the same age.

Question 4.6

Jasmine is adopting a 2-

Caution Jasmine that her child may show problems with attention and indiscriminant friendliness and, if Jasmine is adopting a boy, have special difficulties developing a secure attachment. However, you can also say these problems should improve with loving care.