The Impact of Poverty in the United States

In Chapter 3, I examined the physical effects of extreme poverty—the high rates of stunting in the developing world. While the United States doesn’t have the kind of poverty that causes undernutrition, early-childhood poverty in the United States can compromise a developing life. How common is child poverty in the United States? How does growing up poor affect children’s later well-being?

How Common Is Early-Childhood Poverty?

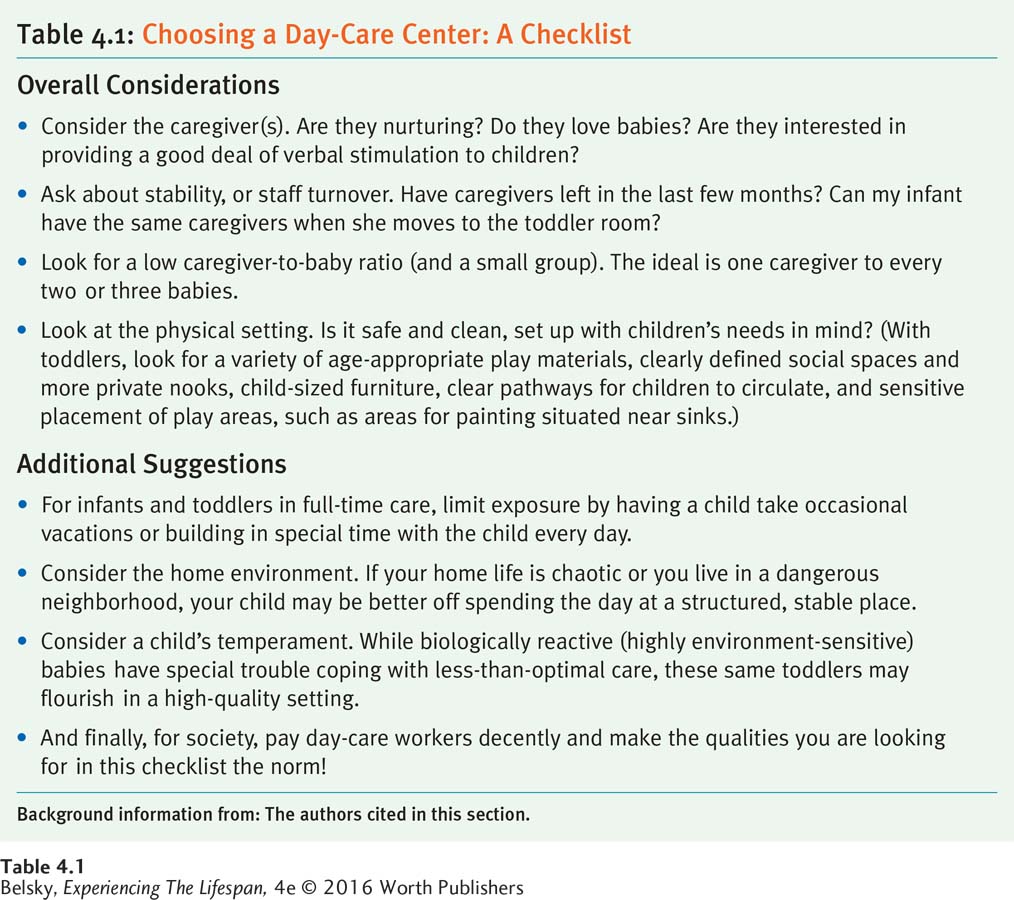

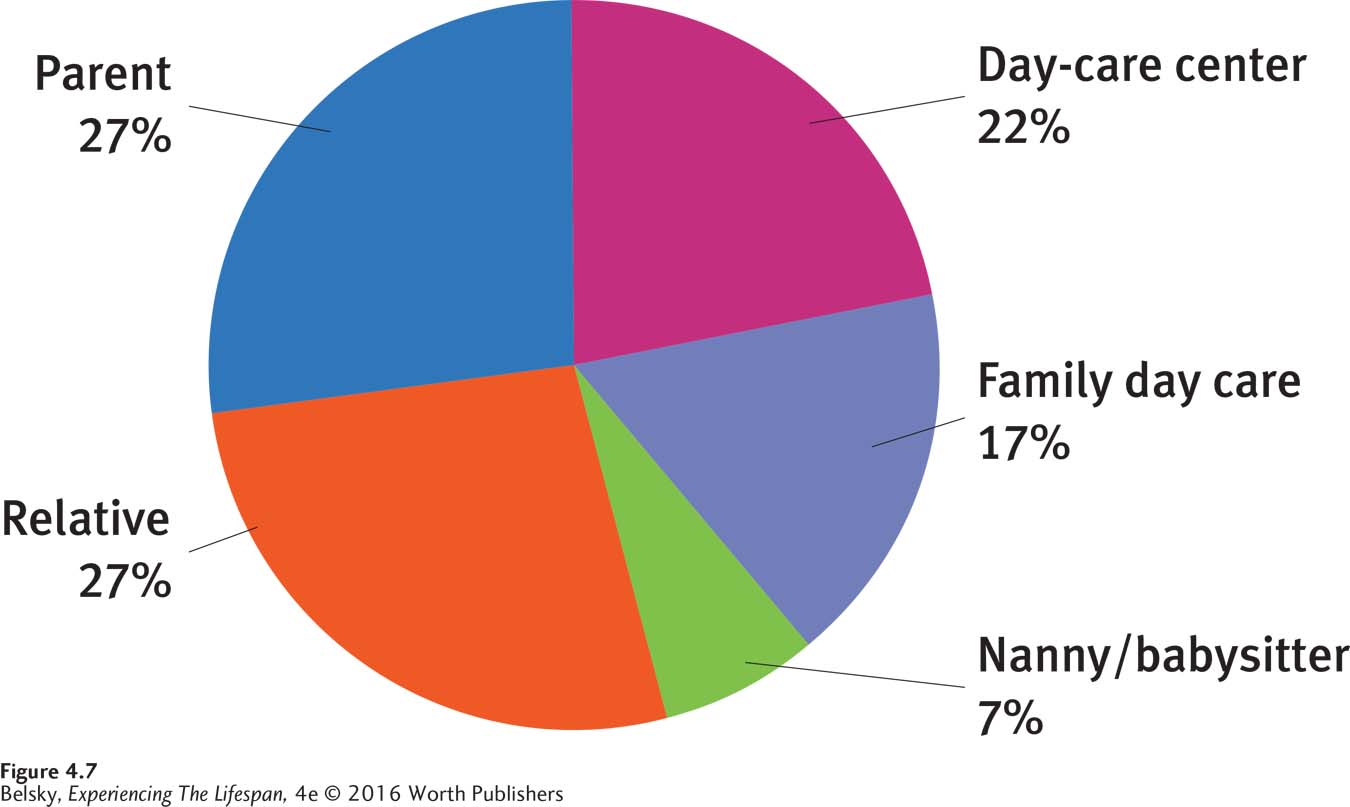

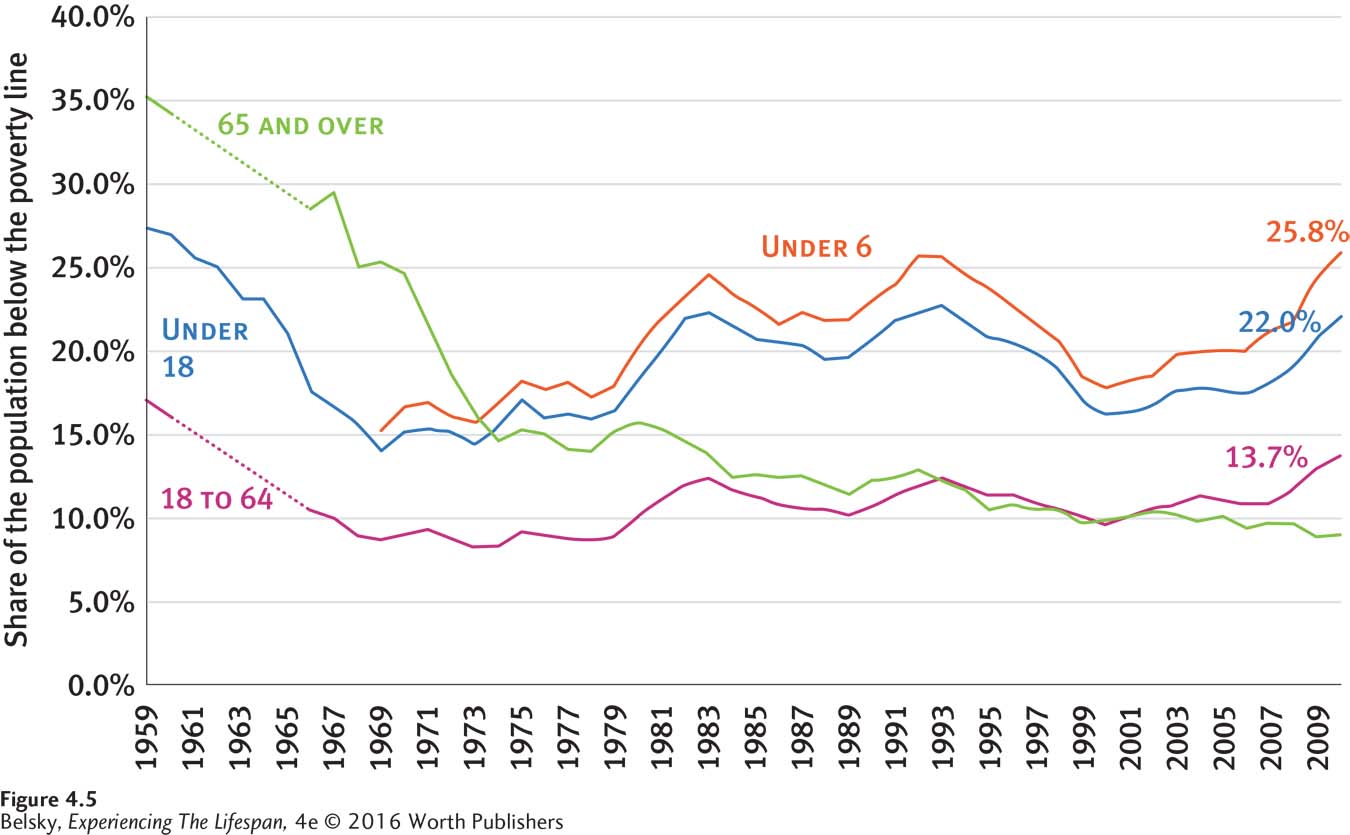

As Figure 4.5, shows, unfortunately, child poverty is prevalent in the United States. In 2013, almost one in four children (22 percent) lived under the poverty line. If we consider children in “low income” families (those earning within two times the official poverty cut-off), the statistic rises to 45 percent (National Center for Children in Poverty [NCCP], 2014)! Moreover, notice that, since the 1970s, young children have been more likely to live in poverty than other age groups in the United States.

Figure 4.5: Poverty rates by age, 1959–2010: Notice that since the 1970s, children under 6 years of age have been more likely to live under the poverty line than other age groups in the United States. (FYI—Although the “poverty line” designation theoretically describes the minimum income needed to survive, experts feel that families need twice that amount of money to really make ends meet.)

Data from: Economic Policy Institute (2012). The State of Working America: Poor children. Retrieved January 12, 2014, http://stateofworkingamerica.org/

One cause is single motherhood. Imagine how difficult it would be as a woman raising a baby alone to work, pay for child care, and still have money to make ends meet. Now imagine how difficult it would be for any person to support a family with a full-time job that pays under $12 an hour. In 2013, more than 1 in 4 U.S. working men, age 25–34, earned less than this amount (Gould, 2014). So, it’s no wonder that economic disadvantage can be the price of starting families during the very time young people are supposed to marry and give birth.

How Does Early-Childhood Poverty Affect Later Development?

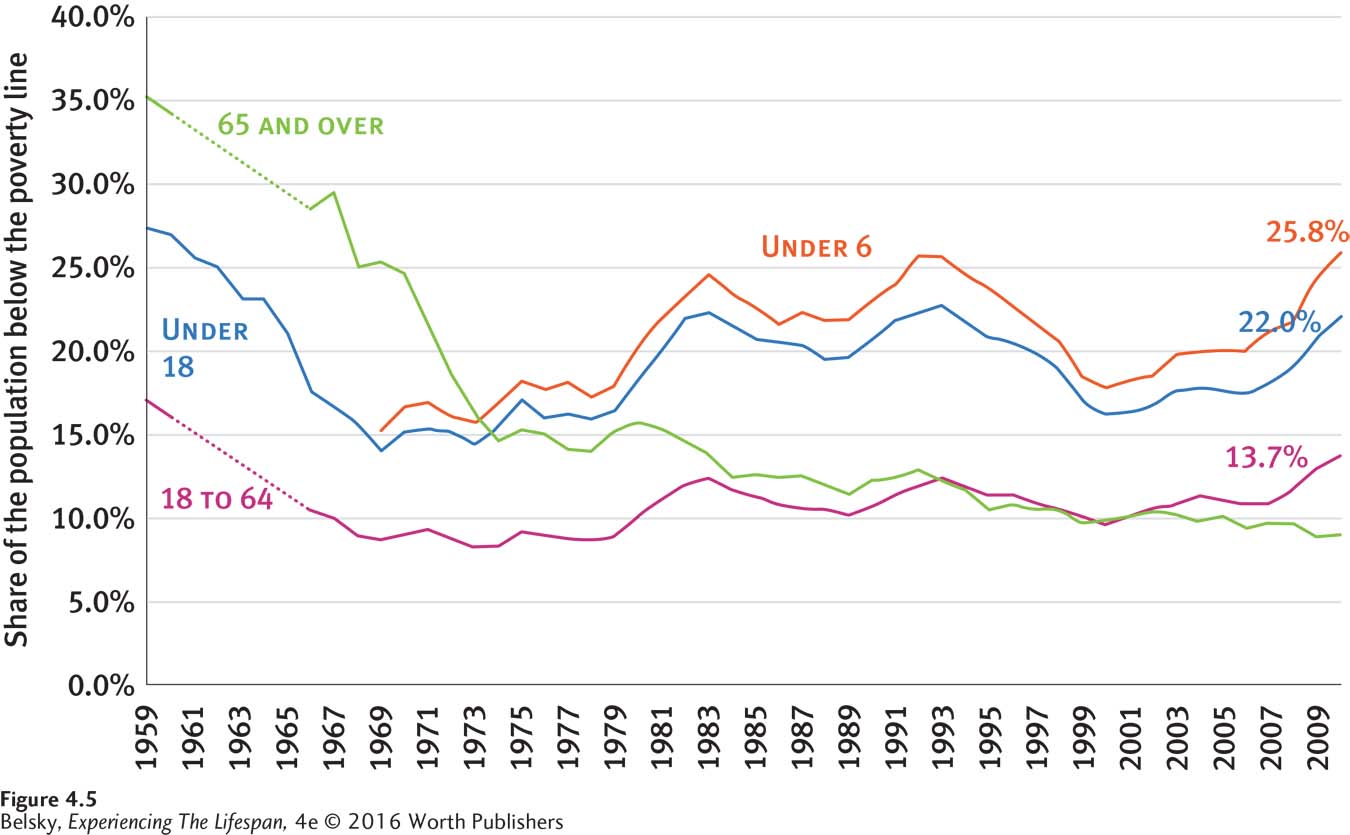

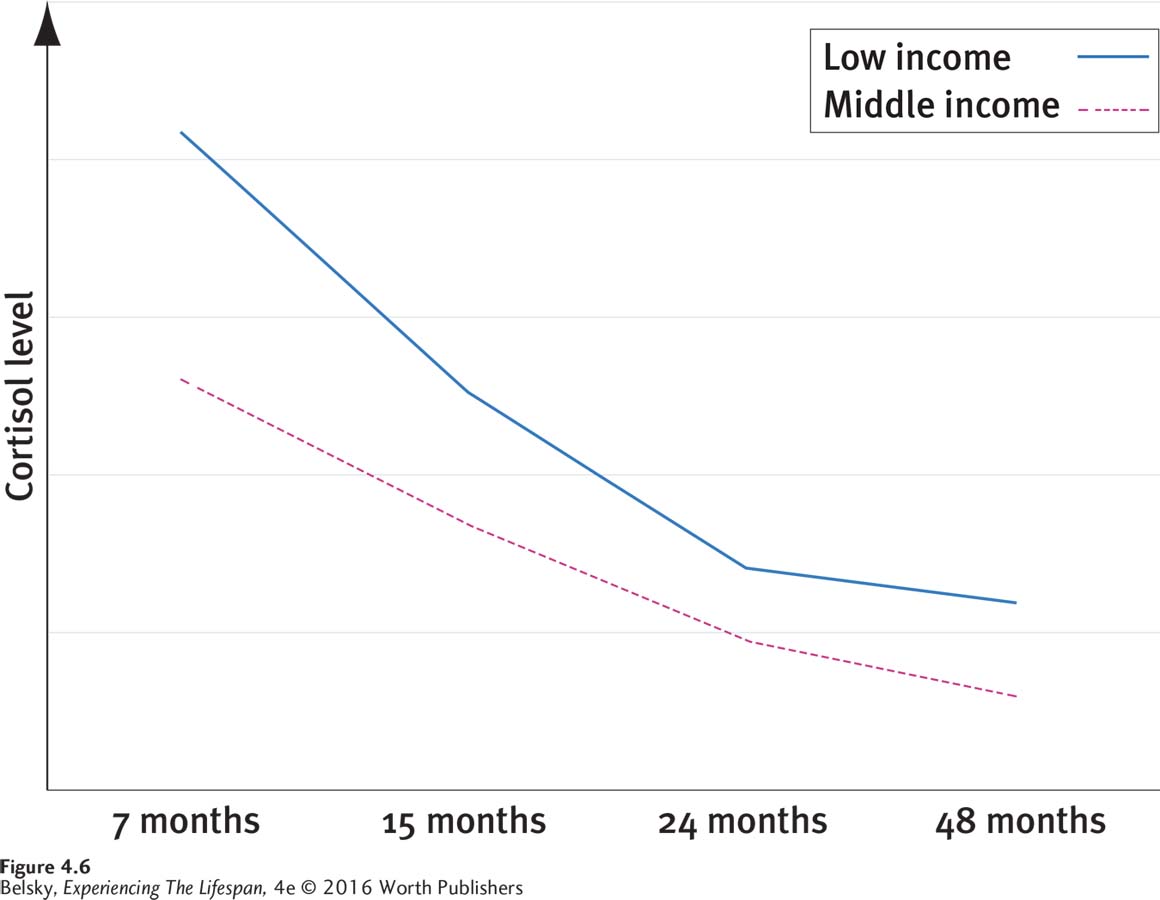

Unfortunately, spending one’s first years of life in poverty can have long-term effects. As Figure 4.6 shows, poor children show chronically elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol (Evans & Kim, 2013), which may wear down the body and promote premature illnesses and death (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011; recall also my discussion of deprivation in the womb, in Chapter 2).

Figure 4.6: Resting cortisol levels among low- and middle-income children from age 7 months through age 4 years: Notice that low-income babies, toddlers, and preschoolers show elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which may impair their ability to regulate their behavior and wear down the body, causing premature illness and death.

Data from: Evans and Kim, 2013, p. 45.

The educational impact is pronounced. You might be surprised to know that being poor during the first four years of life makes it statistically less likely for a child to graduate from high school (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Duncan, Ziol-Guest, &Kalil, 2010).

Why can early-childhood poverty limit later academic success? One possibility is that it is difficult to make up for what you have lost if you enter school “left behind,” not knowing your letters or numbers, without the basic building blocks to succeed. (Kozol, 2005, p. 53.)

Poverty also can impair the attachment dance, especially among at-risk children who need unusually sensitive care. Imagine arriving home exhausted from a low-wage job or being unemployed, food insecure, and worried about getting evicted because you can’t pay the rent. How would you deal with the kind of temperamentally irritable infant I described in the previous section, a baby who was difficult to soothe (Paulussen-Hoogeboom and others, 2007). So although money cannot buy loving parents, it can buy any parent breathing space to try to do her best.

Moreover, poor children may not have the concrete breathing space to learn (Leventhal & Newman, 2010). If a boy or girl lives in crowded, substandard housing or is among the roughly 1 in 3 low-income children in the United States whose family must repeatedly move (Miller, Sadegh-Nobari, & Lillie-Blanton, 2011), it’s hard to focus on academics or get connected to school. And if a child lives in a dangerous area, she cannot escape the household chaos by venturing outside. Her neighborhood is likely to be a scary place (Anakwenze & Zuberi, 2013).

Unfortunately, the impact of a chaotic environment may appear before a child ventures outside. When researchers explored how well 6-month-olds were able to focus their attention, the low-SES babies performed worse than the average child that age (Clearfield & Jedd, 2013).

If you are thinking this research has eerie similarities to the orphanage-caused attention abnormalities, you may be right. However, with poverty, the same earlier (attachment) principles apply. Individual children are more or less genetically reactive to this stress. There is dose–response effect. Deficits in the ability to focus and modulate one’s behavior are more probable if a child has been chronically poor (Raver and others, 2013).

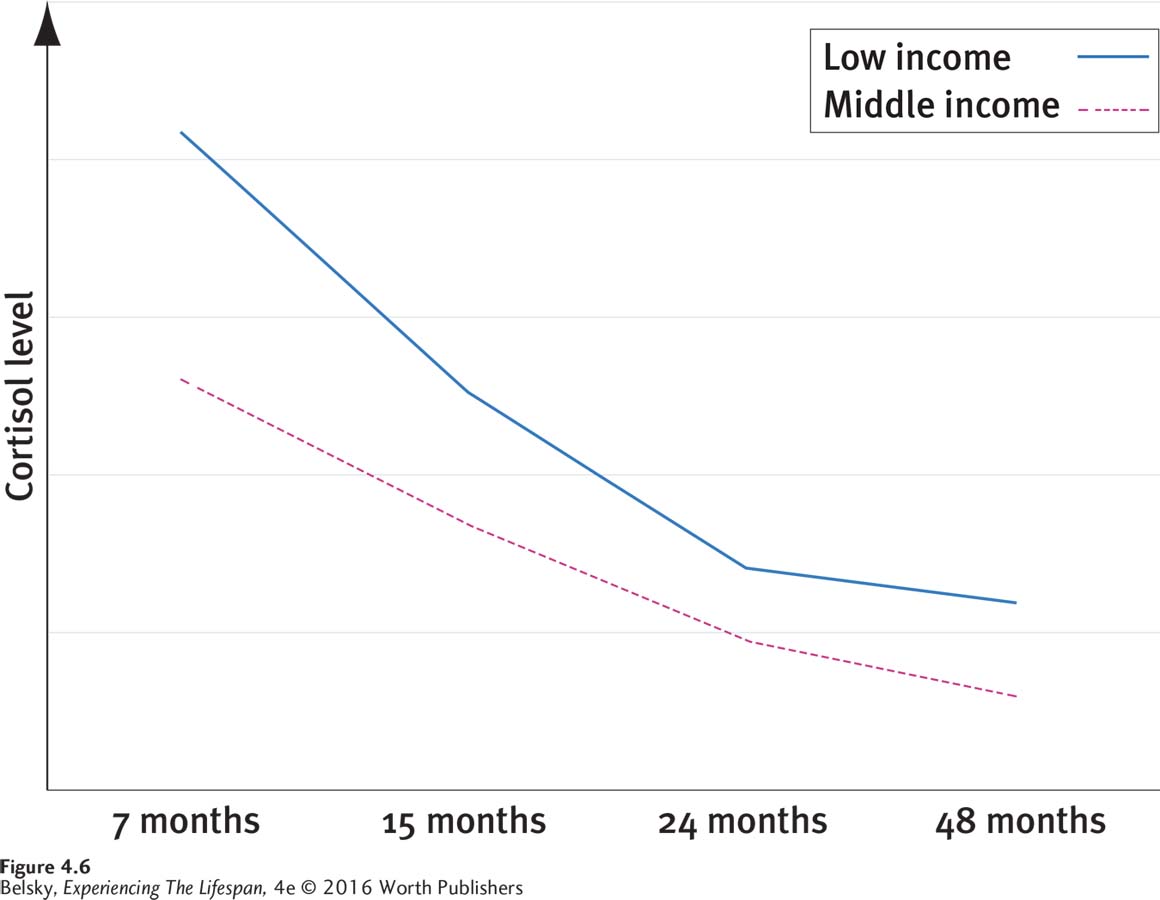

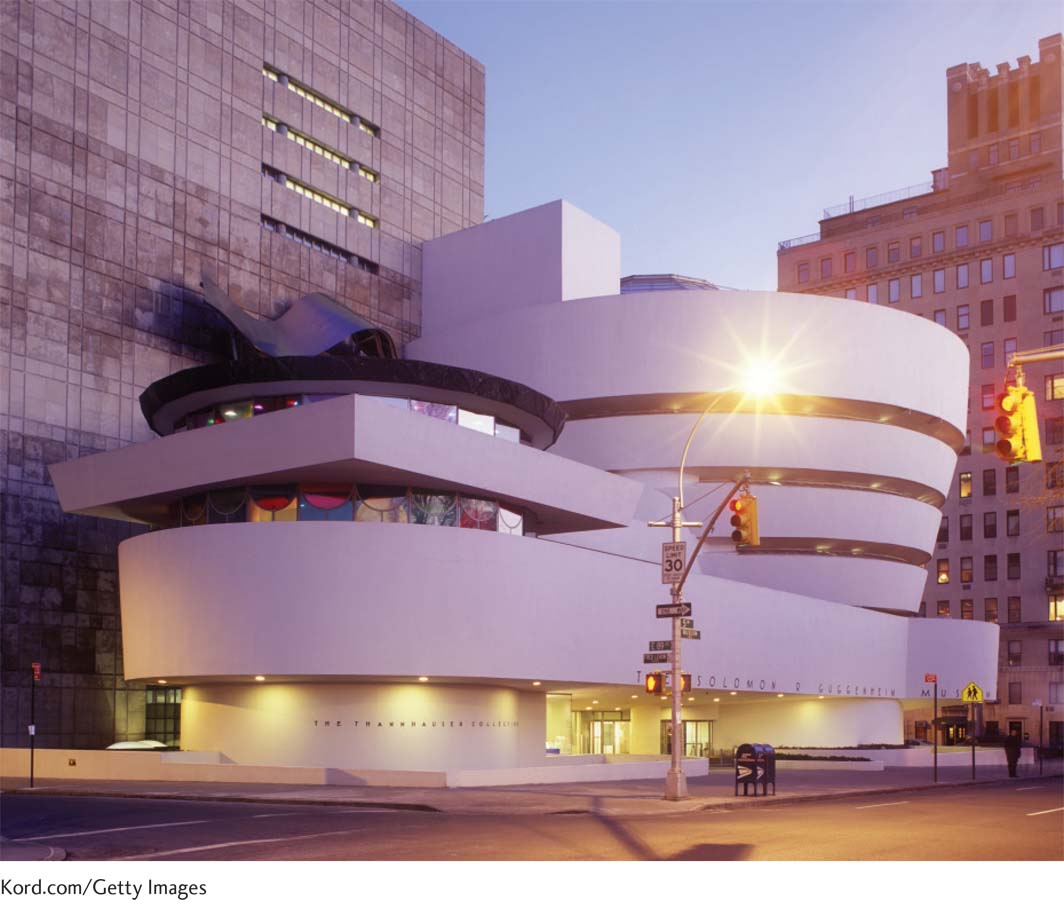

There also is a rural–urban U.S. distinction. While one study suggested the risk of experiencing preschool problems was three times greater if a poor child lived in a large city (versus the country), over a certain economic threshold ($32,000), city preschoolers benefited most (Miller and others, 2013). Blighted, impoverished urban neighborhoods seem especially toxic to young children’s well-being. But having “a bit more money” allows city parents to expose their preschoolers to museums, parks, and the many enriching experiences this kind of world-class environment provides.

Kord.com/Getty Images

Growing up in a bucolic rural setting offers a lovely tranquil childhood, but it can’t top the intellectual stimulation this city provides—explaining why, beyond “a threshold income level,” urban preschoolers do better on early-childhood cognitive tests.

Stan Rohrer/Getty Images

Luckily, low-income parents have access to one enriching experience no matter where they live—Head Start.

INTERVENTIONS: Giving Disadvantaged Children an Intellectual and Social Boost

The famous government program called Head Start, established in 1965, aims to provide the kind of high-quality preschool experience to make poverty-level children as ready for kindergarten as their middle-class peers. By the beginning of the twenty-first century most states also offered free pre-K (prekindergarten) programs targeted to children in economic need (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003).

Early Head Start extends this help to infants and toddlers. This federal program focuses on training parents to be more effective caregivers, as well as supports low-income pregnant women with home visits and other services (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011).

Do these interventions work? The answer is yes. Provided the programs are high quality, study after study shows Head Start and pre-K programs make a difference in low-income children’s lives (Bassok, 2010; Votruba-Drzal, 2013; Magnuson & Shager, 2010; Miller, Sadegh-Nobari, & Lillie-Blanton, 2011; Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011; Li and others, 2013). In a genuine experiment, in which researchers randomly assigned disadvantaged children to a high-quality pre-K, this one-shot intervention had an impact, decades later, in improved college graduation rates! (See Pungello and others, 2010.)

Unfortunately, however, excellent preschools (teaching-oriented group programs beginning at age 3) are most available to affluent young children (Magnuson & Shager, 2010). Moreover, no one-shot magic intervention at age 3 or 4 compensates for the academic barriers poor children face during their entire school careers. As you will learn in Chapter 7, low-income children typically attend the poorest-quality kindergartens. Their educational experiences—without adequate books, mold-encrusted classrooms, and teachers who often quit just a few months into the school year—qualify as a national shame (Kozol, 1988, 2005).

Finally, I must emphasize that preschool doesn’t work in isolation. Yes, early-childhood programs can be a nurturing lifeline for a child whose home environment is poor (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011; Berry and others, 2014). But what matters most is the quality of care at school and home (Crosnoe and others, 2010; Stein and others, 2013).

This brings up that vital influence: parents! Mothers and fathers at every income level differ in the enriching experiences they provide. Every study agrees: What happens at home matters most (Lugo-Gil & Tamis-LeMonda, 2008). Some affluent parents are neglectful. Some poverty-level moms and dads work overtime to nurture their daughters and sons.

Can we identify the core qualities of these special low-income parents? In one study, researchers found that if people felt good about their own childhoods and were optimistic, they could put aside their problems and offer their children the ultimate in tender-loving care (Kochanska and others, 2007). As a student of mine commented, “I don’t see my family in your description of poverty. My mom is my hero. We grew up poor, but in terms of parenting, we were very rich.”

The Impact of Child Care

As a well-off parent, poverty issues can seem distant from your life. Child care affects every family, from millionaires, to middle-class urban mothers and fathers, to the rural poor. One in every two mothers in the United States returns to work during a baby’s first year of life. With child-care costs currently ranging from $5,000 to 15,000 per year, the expense of putting even one baby in day care is daunting, even to couples who are middle class (Palley & Shdaimah, 2011). When we combine these economic concerns (“This is taking up a huge chunk of my paycheck!”) with anxieties about “leaving my baby with strangers,” it makes sense that many new parents struggle to keep child care in the family. They may rely on grandma or juggle work schedules so that one spouse is always home (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011).

People who use paid caregivers have several options. Well-off families often hire a nanny or babysitter. Less-affluent parents, or those who want a more inexpensive option, often turn to family day care, where a neighbor or local parent cares for a small group of children in her home.

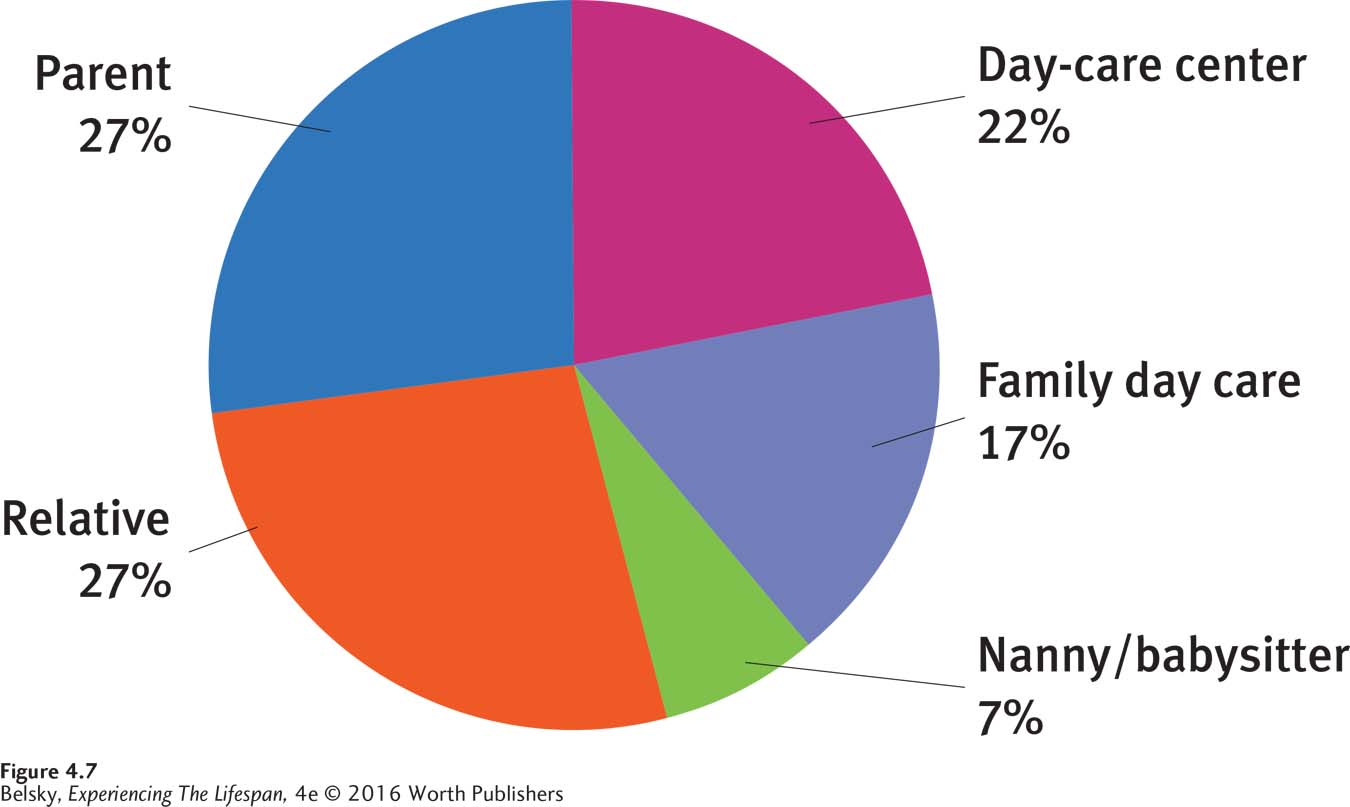

The big change on the child-care landscape has been the dramatic increase in licensed day-care centers—larger settings catering to children of different ages. By the late twentieth century, roughly 1 in 2 U.S. preschoolers attended these facilities. The comparable figure for infants and toddlers was more than 1 in 5 (see Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7: Day-care arrangements for infants and toddlers with employed mothers, late 1990s: Notice that, while most infants and toddlers with working mothers are cared for by other family members, 1 in 5 attend licensed day-care centers.

Data from: Shonkoff & Phillips 2000, p. 304.

Child Care and Development

Imagine you are the mother of an infant and must return to work. You probably have heard the media messages that link full-time day care with less-than-adequate mothering. So you are feeling guilty, and perhaps feel compelled to explain your decision to disapproving family and friends (Fothergill, 2013). You may wonder, “Will my child be securely attached if I see her only a few hours a day?” You certainly worry about the quality of care your child would receive: “Will my baby get enough attention at the local day-care center?” “Am I really harming my child?”

To answer these kinds of questions, in 1989, developmentalists began the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care. They selected more than 1,000 newborns in 10 regions of the United States and tracked the progress of these children, measuring everything from attachment to academic abilities, from mental health, to mothers’ caregiving skills. They looked at the hours each child spent in day care, and assessed the quality of each setting. The NICHD newborns are being followed as they travel into adult life (Vandell and others, 2010).

The good news is that putting a baby in day care does not weaken the attachment bond. Most infants attending day care are securely attached to their parents. The important force that promotes attachment is the quality of the dance—whether a parent is a sensitive caregiver—not whether she works (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011; Nomaguchi and DeMaris, 2013). Moreover, as I emphasized earlier, what happens at home is the crucial influence affecting how young children develop, outweighing long hours spent in day care during the first years of life (Belsky and others, 2007b; Stein and others, 2013).

However, when we look just at the impact of spending those long hours, the findings are less upbeat. As you saw in the previous section, attending an excellent preschool has intellectual benefits (Vandell and others, 2010). But when we look at the impact of attending day care throughout the first five years of life, there is troubling news.

Earlier NICHD research raised alarm bells by reporting that children who spent long hours in “nonrelative care” were slightly more likely to be rated as “difficult to control” by caregivers and kindergarten teachers (NICHD, Early Child Care Research Network, 2003, 2004, 2006; see also Coley and others, 2013). Now we know that long hours spent in day care, beginning early in life, still predict an elevated risk of “acting-out issues” as teens (Vandell and others, 2010).

These results do not offer comfort to the millions of parents with babies who rely heavily on day care. Luckily, the correlations are weak (Vandell and others, 2010). Because these settings can be a refuge from the chaotic home environments described earlier, for infants living in poverty, attending full-time day care may promote well-being (Berry and others, 2014). Moreover, day care’s negative effects apply mainly to children attending large centers, not smaller, family day care (Groeneveld and others, 2010; Coley and others, 2013).

What is the trouble with day-care centers? For hints, let’s scan the state of child care in the United States.

Exploring Child-Care Quality in the United States

Visit several facilities and you will immediately see that U.S. day care varies in quality. In some places, babies are warehoused and ignored. In others, every child is nurtured and loved.

The essence of quality day care again boils down to the dance—that is, the attachment relationship between caretakers and the children. Children develop intense attachments to their day-care providers. If a particular caregiver is sensitive, a child in her care tends to be securely attached (Ahnert, Pinquart, & Lamb, 2006; De Schipper and others, 2008).

Child-care providers and parents agree: To be effective in this job, you need to be patient, caring, empathic, and child-centered (Berthelsen & Brownlee, 2007; Virmani & Ontai, 2010). It’s not so much formal education that matters, but being able to reflect on your interactions (Virmani & Ontai, 2010) and being committed to this field (Martin and others, 2010).

You also need to work in a setting where you can relate to children in a one-to-one way. To demonstrate this point, researchers videotaped teachers at 64 Dutch preschools, either playing with three children or with five. Teachers acted more empathic in the three-child group. They were more likely to criticize and get angry with the group of five (de Schipper, Riksen-Walraven, & Geurts, 2006). These differences in teachers’ tone and style were especially pronounced with younger children (the 3-year-olds). So, group size matters; and the lower the child–teacher ratio, the better, especially earlier in life.

Can these day-care workers give enough attention to the babies, toddlers, and preschoolers in their care? Unfortunately, with a child–caregiver ratio at over 3 to 1 at this center, the answer may be no.

© Picture Partners/Alamy

Another important dimension is consistency of care (Harrist, Thompson, & Norris, 2007). Forming an attachment takes time. Therefore, children are more apt to be securely attached to a caregiver when that person has been there a longer time (Ahnert, Pinquart, & Lamb, 2006).

However, partly because of the abysmal pay (in the United States, it’s often close to the minimum wage), day-care workers are apt to quit. They may feel rejected even when they have valuable input to provide. As one woman in an interview study complained, “When . . . you try to tell them (some parents) anything, it’s like ‘yeah right.’ They never want to hear what you have to say” (quoted in Fothergill, 2013, p. 440).

Now, combine this feeling of being unappreciated, with burnout from being overwhelmed. While the recommended ratio is one caregiver to four toddlers, only eight states follow this guideline (Stebbins & Knitzner, NCCP, 2007). Some allow as many as one teacher per 12 children, even during the first year of life.

In sum, now we know why day-care centers are at risk of providing inadequate care. Their culprit is size. In family day care, there is a smaller number of children and often more stability (since the person is watching the children in her home) than in a large facility, where caregivers keep leaving and babies can be warehoused in larger groups (Gerber, Whitebrook, & Weinstein, 2007; Ahnert, Pinquart, & Lamb, 2006; Groeneveld and others, 2010).

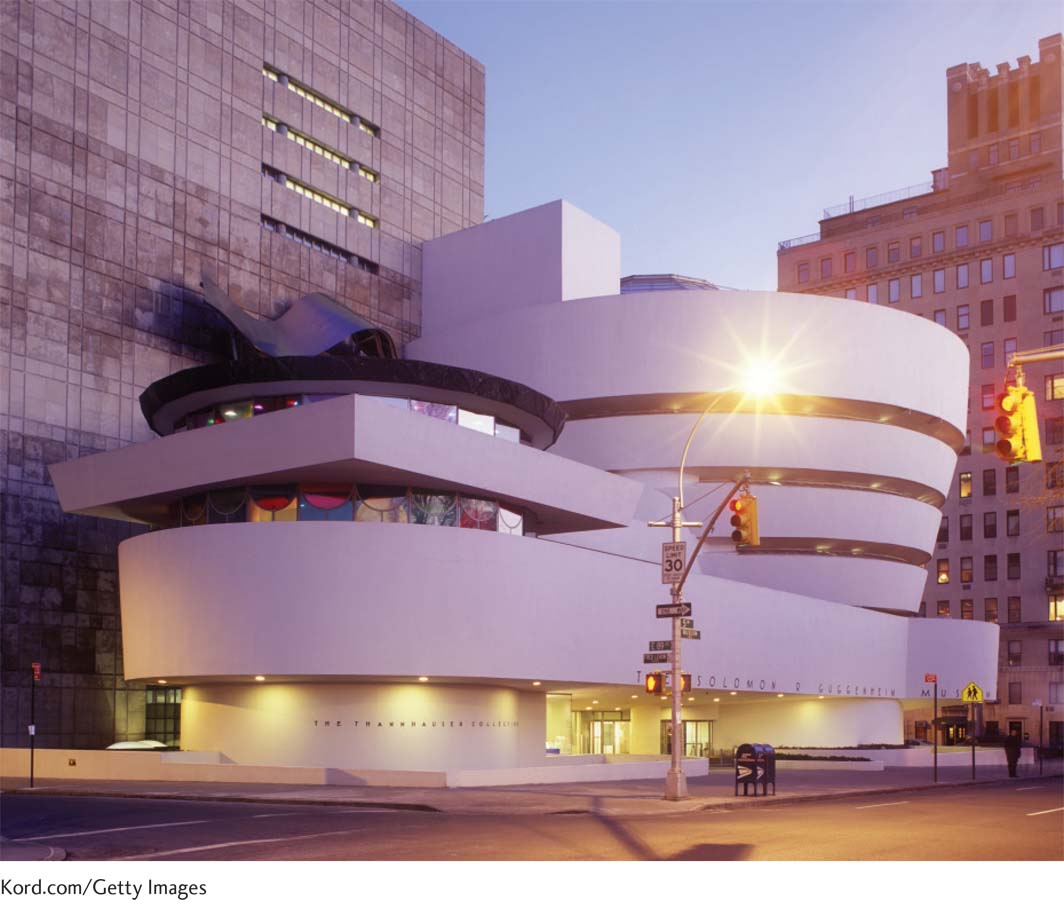

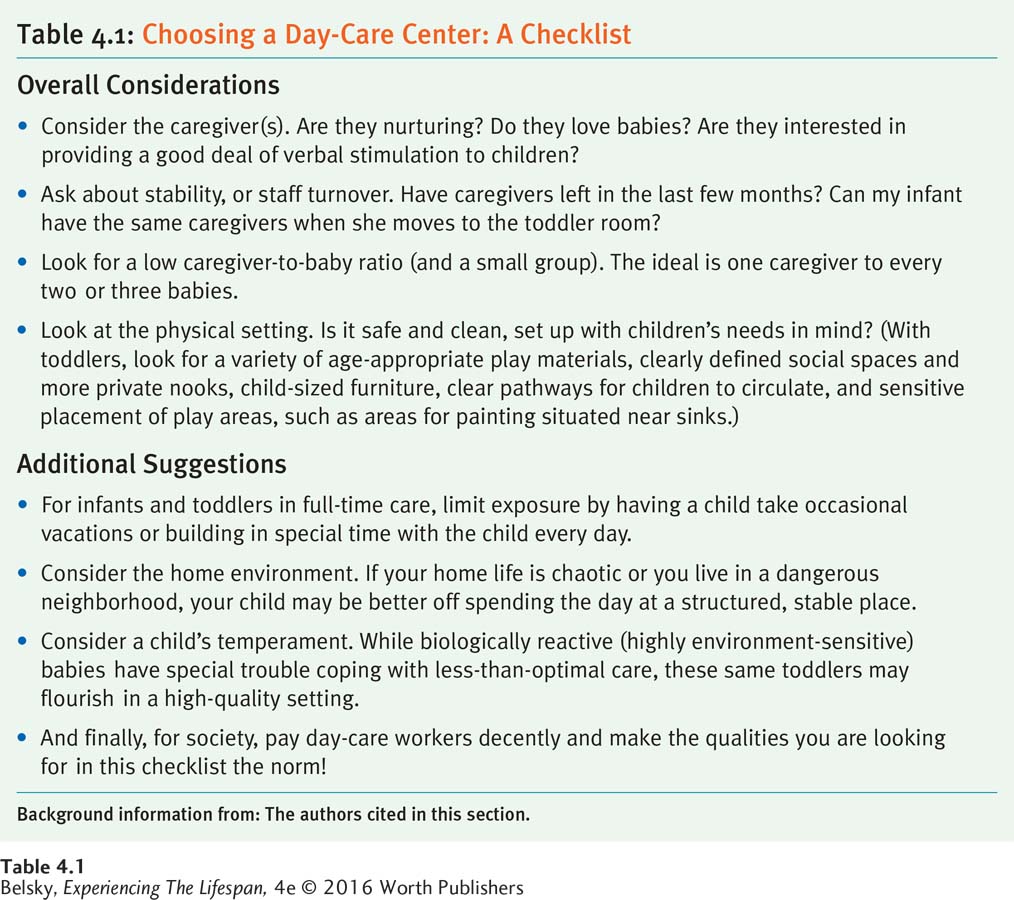

INTERVENTIONS: Choosing Child Care

Given these findings, what should parents do? The take-home message is not “avoid a day-care center,” but rather “choose the best possible place.” Look for a low staff turnover; see if the caregivers are empathic and warm; if you have an infant or toddler, make sure your baby will spend the day in a small group. You might find these conditions at your next-door neighbor’s house. Perhaps you’ll find these attributes at the largest child-care facility in town.

Finally, here, too, we can look to the child’s biology. While attending a low-quality day care is harmful for infants and toddlers with an environment-responsive genetic profile, these same children may flourish if a program is top notch (Belsky and Pluess, 2013). So, as we learn more about environment-sensitive genes, making blanket generalizations—such as “day care is bad (or good)”—may not be appropriate. It depends on the quality of the program, a person’s home life, and, now, the biology of a given child.

Table 4.1 draws on these messages in a checklist. And if you are a parent who relies heavily on day care, keep those guilty thoughts at bay. Your child may blossom at a high-quality day care. Moreover, your responsiveness matters most. You are your child’s major teacher and the major force in making your child secure.

Now that we have examined attachment, poverty, and day care, it’s time to turn directly to the topic I have been implicitly talking about all along—being a toddler.