5.5 Specific Social Cognitive Skills

Language makes us capable of uniquely human social cognitive understandings. We are the only species that reflects on our past and future (Fivush, 2011). The essence of being human, as I highlighted at the beginning of this chapter, is that we effortlessly transport ourselves into each other’s heads, decoding what people are thinking from their own point of view. How do children learn they have an ongoing life history? When do we fully grasp that “other minds” are different from our own?

Constructing Our Personal Past

Autobiographical memories refer to reflecting on our life histories: from our earliest memories at age 3 or 4, to that incredible experience we had at work last week. Children’s understanding that they have a unique autobiography is scaffolded through a specific kind of talk. Caregivers reminisce with young children: “Remember going on a train to visit Grandma?” “What did we do at the beach last week?” These past-

Past-

INTERVIEWER TO 6-

CHILD: It was driving me crazy.

INTERVIEWER: Really?

CHILD: Yes, I was so scared because I didn’t know any of the people and I couldn’t see mom and dad. They were way on top of the audience. . . . Ummm, we were on a slippery surface and we all did “Where the Wild Things Are” and we . . . Mine had horns sticking out of it . . . And I had baggy pants.

(adapted from Nelson & Fivush, 2004)

As this girl reaches adolescence, she will link these kinds of memories to each other, and construct a timeline of her life (Habermas, Negele, & Mayer, 2010; Chen, McAnally, & Reese, 2013). By about age 16, she will use these events to reflect on her enduring personality (“This is the kind of person I am, as shown by how I felt at age 4 or 5 or 9”). Then she will have achieved that Eriksonian milestone—

Caregivers can help stimulate autobiographical memory by sensitively asking questions about exciting experiences they shared with their child (Valentino and others, 2014). (“Wasn’t the Circus amazing! What did you like best?”) Moreover, the quality of our teenage autobiographical memories vary depending on the loving past talk experiences we receive. In one study, young teens who produced rich personal autobiographies were apt to report close, trusting relationships with their mothers (Bosmans and others, 2013). Conversely, overly general autobiographical memories (“I used to go shopping”) rather than recalling specific events (“I remember how I went to Green Hills Mall on that Tuesday with my friends”) can be a symptom of an unhappy life (Valentino and others, 2014). In another study, having been abused, plus an inability to recall details about one’s past, was linked to a young teen’s experiencing depression down the road (Stange and others, 2013).

The most chilling example of this autobiographical memory failure (Freud might label it repression) occurred when researchers tested children who were removed from an abusive home. If a parent was insecurely attached, a child either was apt to make false statements about what took place that day or to deny remembering anything about the traumatic event (Melinder and others, 2013).

160

The take-

Moreover, when researchers train parents in the rich reminiscence styles described above, they find that past-

Making Sense of Other Minds

Listen to 3-

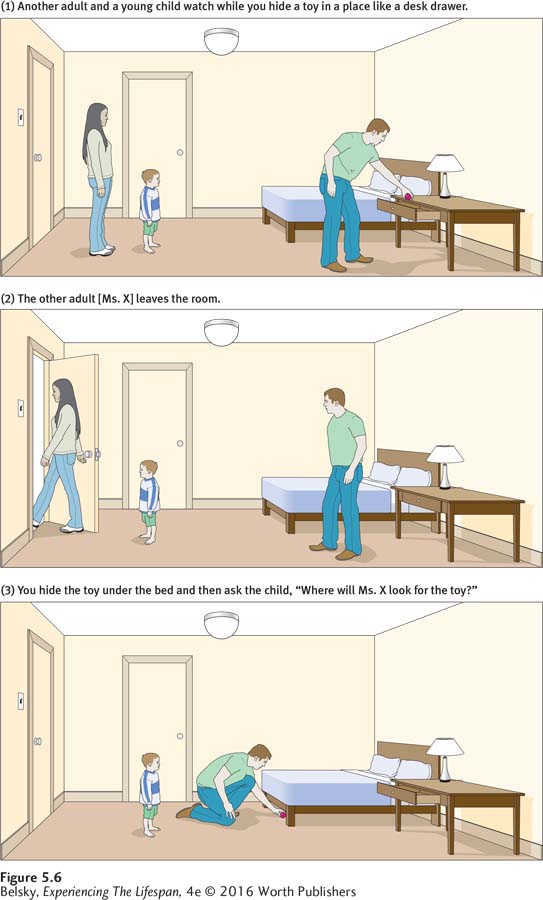

With a friend and a young child, see if you can perform this classic theory of mind task in Figure 5.6 (Wimmer & Perner, 1983). Hide a toy in a place (location A) while the child and your friend watch. Then, have your friend leave the room. Once she is gone, move the toy to another hiding place (location B). Next, ask the child where your friend will look for the toy when she returns. If the child is under age 4, he will typically answer the second hiding place (location B), even though your friend could not possibly know the toy has been moved. It’s as if the child doesn’t grasp the fact that what he observed can’t be in your friend’s head, too.

What Are the Consequences and Roots of Theory of Mind?

Having a theory of mind is not only vital to having a real conversation; it is crucial to convincing someone to do what you say. Researchers asked children to persuade a puppet to do something aversive, either eat broccoli or brush its teeth. Even controlling for verbal abilities, the number of arguments a given boy or girl made was linked to advanced theory of mind (Slaughter, Peterson, & Moore, 2013).

Theory of mind is essential to understanding people may not have your best interests at heart. One developmentalist had children play a game with “Mean Monkey,” a puppet the experimenter controlled (Peskin, 1992). Beforehand, the researcher had asked the children which sticker they wanted. Then, she had Mean Monkey pick each child’s favorite choice. Most 4-

A remark from one of my students brings home the real-

The false-

Do Individual Children (and Adults) Differ in Theory of Mind?

While most preschoolers pass theory-

161

Conversely, because they have so much hands-

162

Bilingual preschoolers—

My discussion implies that interpersonal or social skills are intimately involved in grasping theory-

Hot in Developmental Science: Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) actually are defined by deficits in theory of mind—

Unlike ADHD, the symptoms of autism spectrum disorders routinely appear in early childhood and persist, wreaking lifelong havoc. Deteriorating executive functions (Rosenthal and others, 2013), poor social understanding (Bal and others, 2013), and worsening vocational adjustment (Taylor & Mailick, 2014) can be an unfortunate path this disorder takes during the adult years.

163

The good news is that in contrast to ADHD, this fuzzy, multi-

What causes these devastating brain conditions? The fact that autism spectrum disorders run in families suggests these diseases may partly have genetic causes (Rosti and others, 2014). A puzzling array of environmental risk factors have been linked to autism, from air pollution (Volk and others, 2013), to maternal abusive relationships (Roberts and others, 2013); from prenatal medication use (Christensen and others, 2013), to having a premature birth. Given that pregnancy and birth problems seem involved, it’s no surprise that older parents are at higher risk of having a child with this condition. But astonishingly, one study traced the risk back a generation—

What are the treatments? The most well-

164

Unfortunately, however, despite decades of nonstop media attention, little progress has been made at finding a magic-

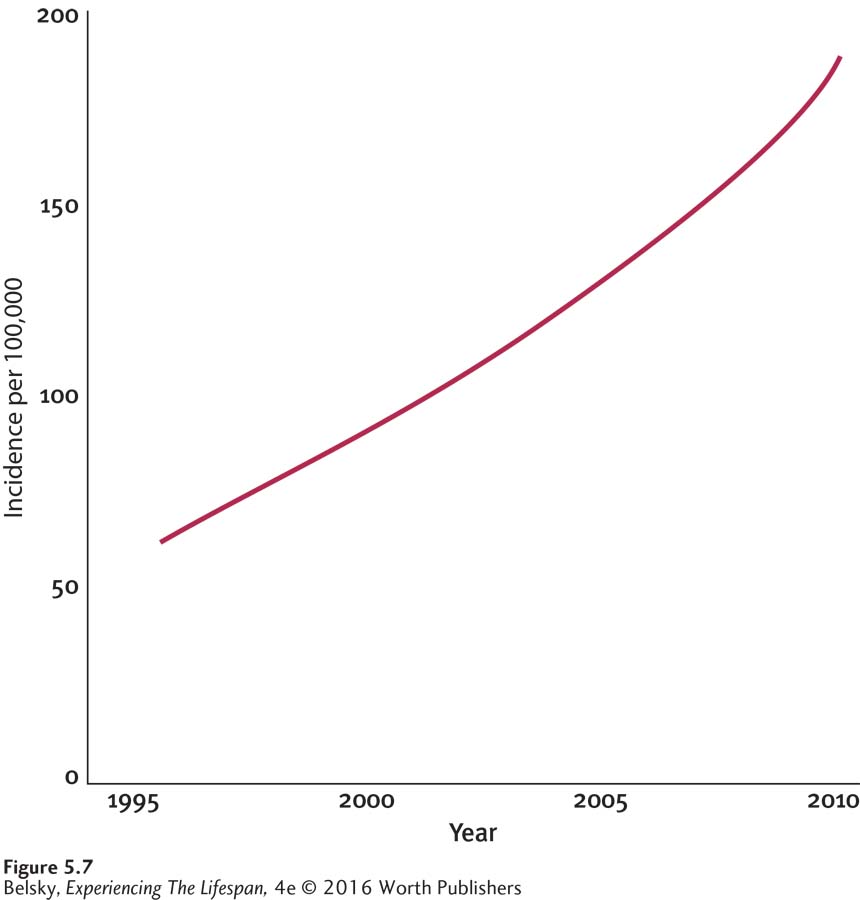

Autism spectrum disorders are poster-

Tying It All Together

Question 5.16

Andrew said to Madison, his 3-

This past-

Question 5.17

Pick the statement that would not signify that a child has developed a full-

He’s having a real give-

and- take conversation with you. He realizes that if you weren’t there, you can’t know what’s gone on—

and tries to explain to you what happened while you were absent. When he has done something he shouldn’t do, he is likely to lie.

He’s learning to read.

d

Question 5.18

Autism spectrum disorders are becoming more/less prevalent, and we are making great progress/not making much progress in determining their causes.

Autism spectrum disorders are becoming more prevalent, and we are not making great progress in determining their causes.