7.3 School

What was that test Josiah (in the introductory chapter vignette) took, and what does intelligence really mean? What makes for good teaching and superior schools? Before looking at these school-

Setting the Context: Unequal at the Starting Gate

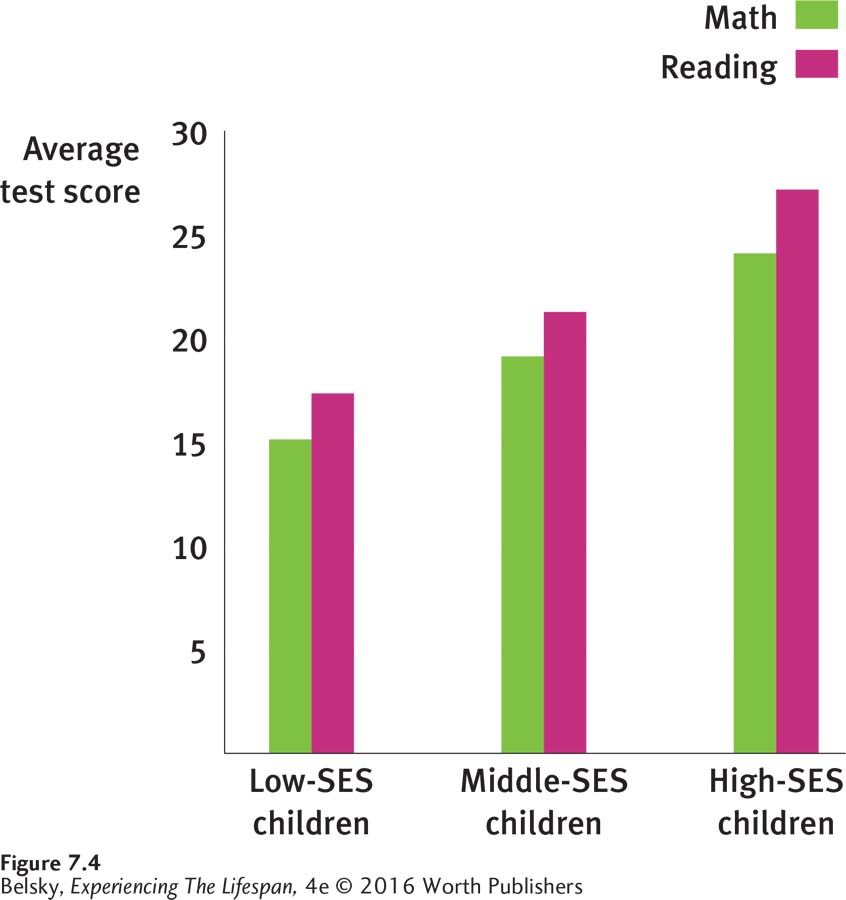

In Chapter 4, you learned that living in poverty for the first years of life has damaging effects on cognition. Figure 7.4 reveals that devastation directly by offering sobering statistics with regard to a turn of the century entering U.S. kindergarten class (Lee & Burkam, 2002). Notice that children from low-

You would think that when children start a race miles behind, they should be given every chance to catch up. The reality is the reverse. From class size, to the quality of teacher training, to the attractiveness of the physical building—

213

The consistency of these findings . . . is . . . troubling. The least advantaged of America’s children, who also begin their formal schooling at a substantial cognitive disadvantage, are systematically mapped into our nation’s worst schools.

(Lee & Burkam, 2002, p. 77)

Now, let’s keep these inequalities in mind as we explore the controversial topic of intelligence tests.

Intelligence and IQ Tests

What does it mean to be intelligent? Ask classmates the question, and they will probably mention both academic and “real life” skills (Sternberg, Grigorenko, & Kidd, 2005). Conceptions of what it means to “be intelligent” differ from society to society, and among different ethnic groups. Latino parents, for instance, focus more on social competence (getting along with people), while our mainstream culture views intelligence in terms of cognitive traits (Sternberg, 2007).

Traditional intelligence tests reflect the mainstream view. They measure only cognitive abilities. Intelligence tests, however, differ from achievement tests—the yearly evaluations children take to measure knowledge in various subjects. The intelligence test is designed to predict a person’s general academic potential, or ability to master any school-

Examining the WISC

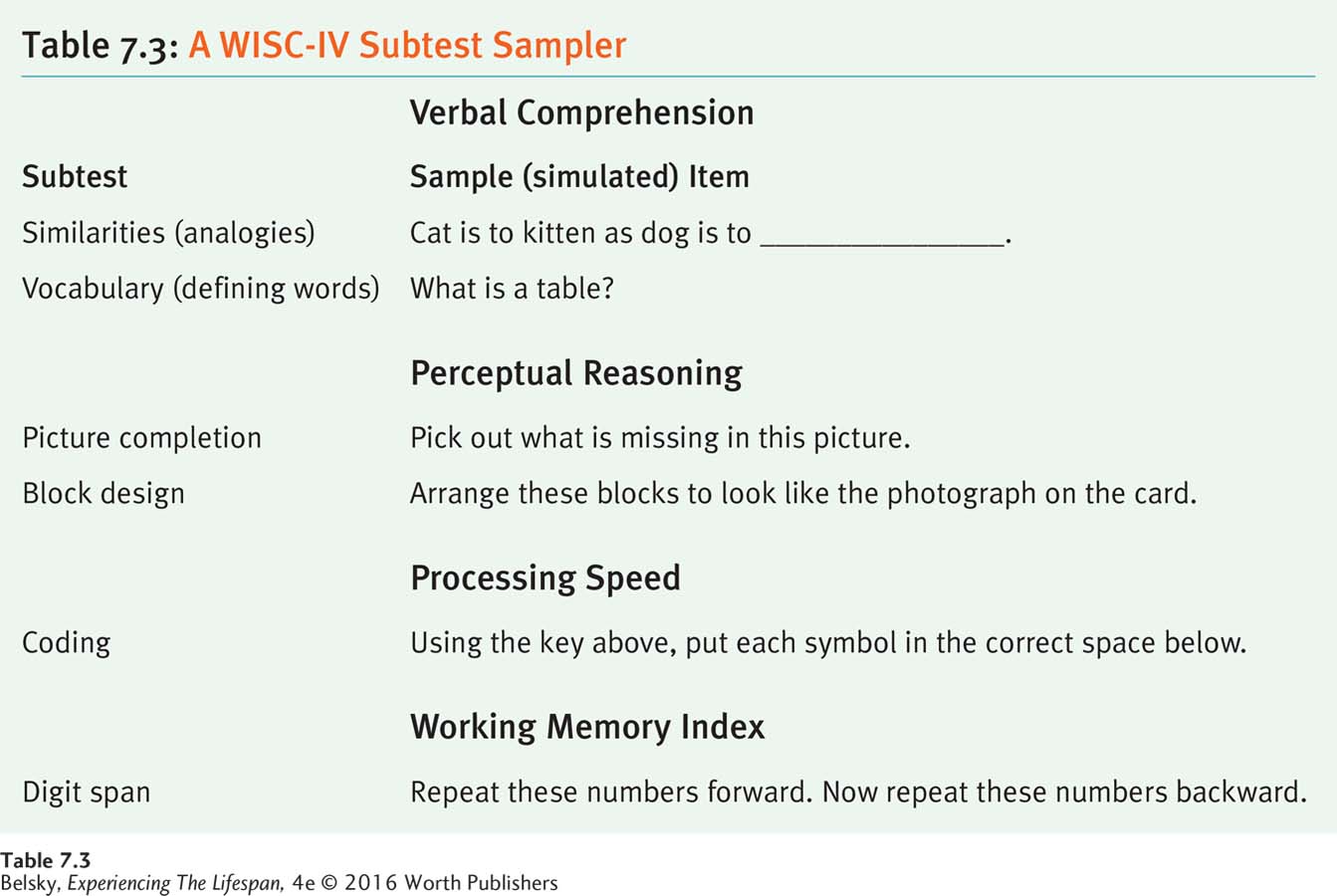

The WISC (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children), now in repeated revisions, was devised by David Wechsler and is the current standard intelligence test. As you can see in Table 7.3, the WISC samples a child’s performance in a variety of areas. However, as it is divided into main sections—

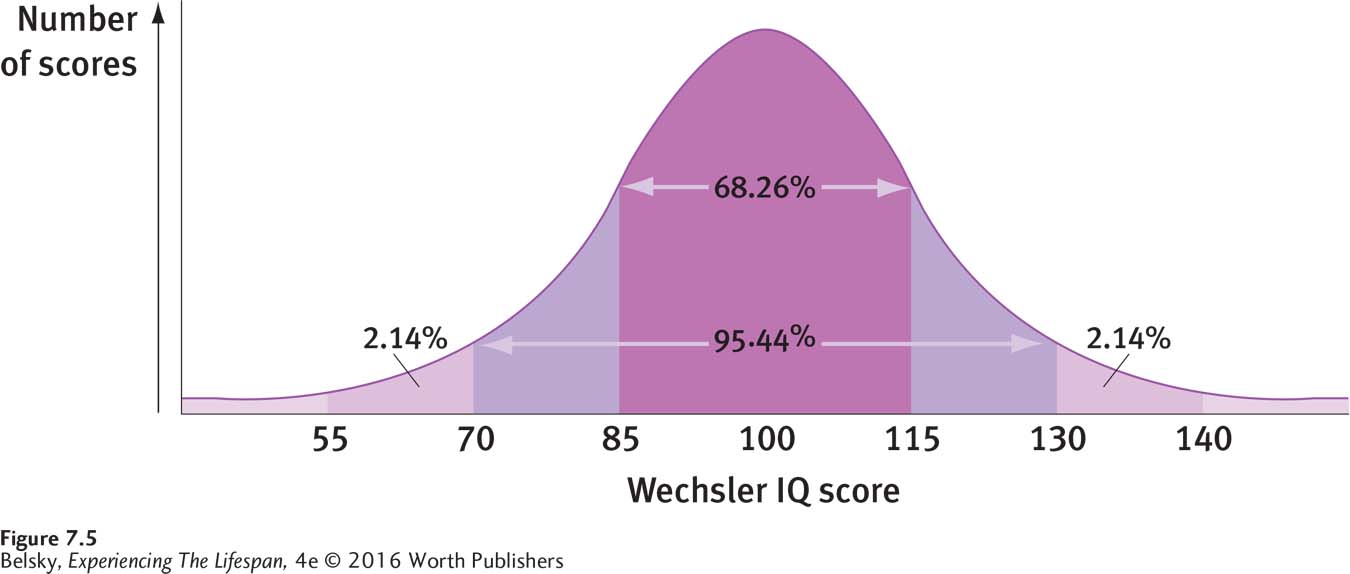

Achievement tests are administered to groups. The WISC is given individually to a child by a trained psychologist, a process that often includes several hours of testing and concludes with a written report. If the child scores at the 50th percentile for his age group, his IQ is defined as 100. If that child’s IQ is 130, he ranks at roughly the 98th percentile, or in the top 2 percent of children his age. If a child’s score is 70, he is at the opposite end of the distribution, performing in the lowest 2 percent of children that age. Put on a graph, this score distribution, as you can see in Figure 7.5, looks like a bell-

214

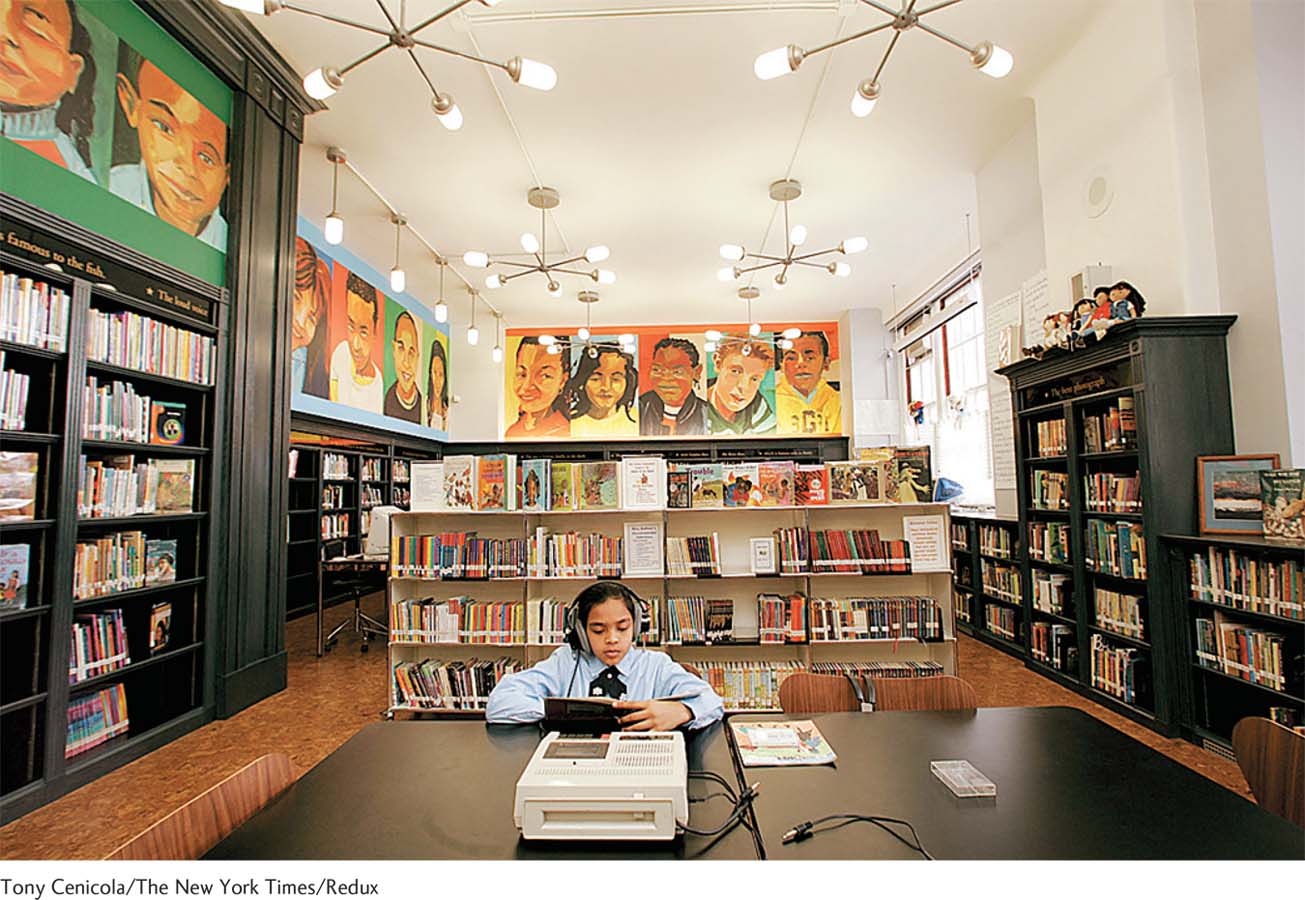

When do children take this test? The answer, most often, is during elementary school when there is a question about a given child’s classroom performance. School personnel then use the IQ score as one component of a multifaceted assessment, which includes achievement test scores, teachers’ ratings, and parents’ input, to determine whether a boy or girl needs special help (Sattler, 2001). If a child’s low score (under 70) and other behaviors warrant this designation, she may be classified as intellectually disabled. If a child’s IQ is far higher than would be expected, compared to her performance on achievement tests, she is classified as having a specific learning disorder, an umbrella term for any impairment in language or difficulties related to listening (such as ADHD), thinking, speaking, reading, spelling, or math.

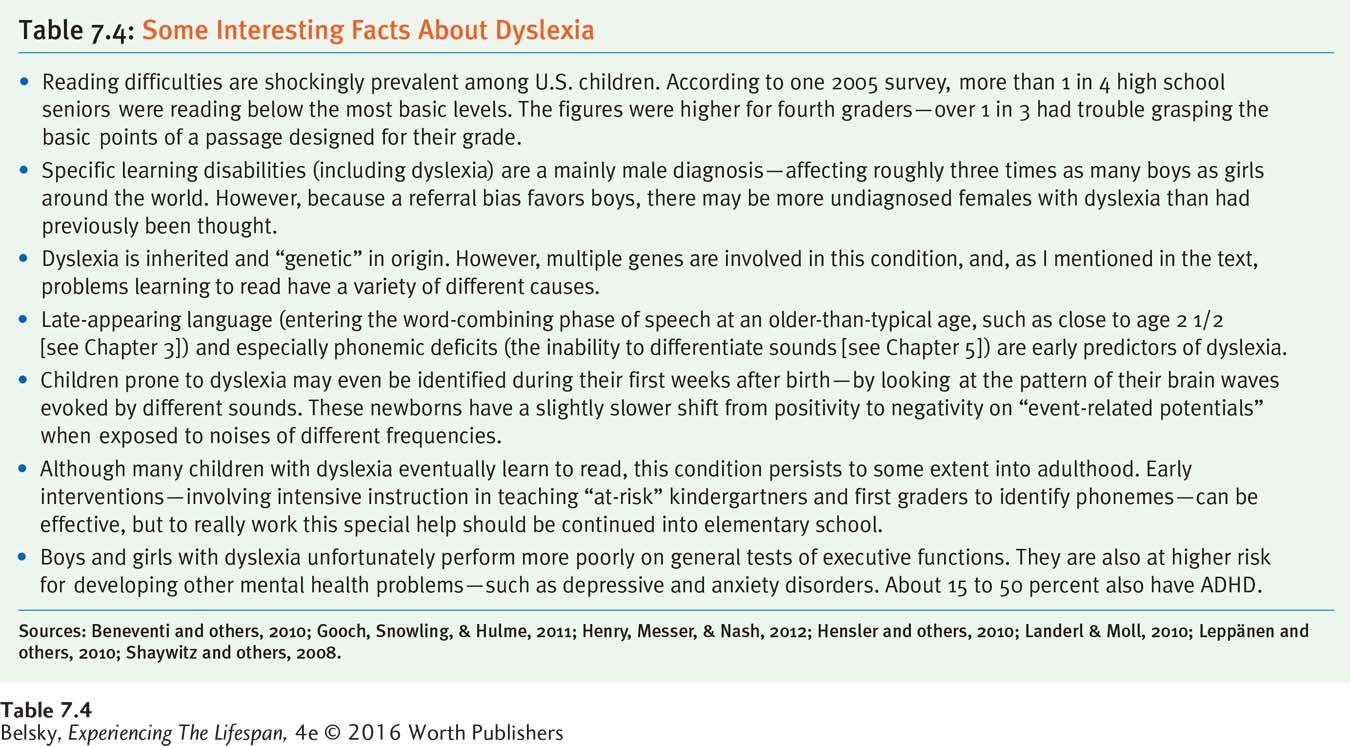

Although children with learning disabilities often score in the average range on IQ tests, they have trouble with schoolwork. Many times, they have a debilitating impairment called dyslexia that undercuts every academic skill. Dyslexia, a catchall term referring to any reading disorder, may have multiple causes (Nicolson & Fawcett, 2011; Zoccolotti and Friedmann, 2010). What’s important is that, despite having good instruction and doing well on tests of intelligence, a dyslexic child is still struggling to read (Shaywitz, Morris, & Shaywitz, 2008).

My son, for instance, has dyslexia, and our experience shows just how important having a measure of general intelligence can be. Because Thomas was falling behind in the third grade, my husband and I arranged to have our son tested. Thomas was defined as having a learning disability because his IQ score was above average but his achievement scores were well below the norm for his grade. Although we were aware of our son’s reading problems, the testing was vital in easing our anxieties. Thomas—

Often, teachers and parents urge testing for a happier reason: They want to confirm that a child is intellectually advanced. If the child’s IQ exceeds a certain number, typically 130, or in the top 2 percent (see Figure 7.4), she is labeled gifted and is eligible for special programs. In U.S. public schools, the law mandates intelligence testing before children can be assigned to a gifted program or remedial class (Canter, 1997; Sattler, 2001).

Table 7.4 offers a fact sheet about dyslexia. The Experiencing the Lifespan box provides a firsthand view of what it is like to triumph over this debilitating condition. Now that we have explored the measure and when it is used, let’s turn to what the scores mean.

215

Experiencing the Lifespan: From Dyslexic Child to College Professor Adult

Aimee Holt, a colleague of mine who teaches our school psychology students, is beautiful and intelligent, the kind of golden girl you might imagine would have been a great childhood success. When I sat down to chat with Aimee about her struggles with dyslexia and other learning disabilities, I found first impressions can be very misleading:

In first grade, the teachers at school said I was mentally retarded. I didn’t notice the sounds that went along with letters. I walked into walls and fell down a lot. My parents refused to put me in a special school and finally got me accepted at a private school, contingent on getting a good deal of help. I spent my elementary school years being tutored for an hour before school, an hour afterwards, and all summer.

Socially, elementary school was a nightmare . . . I remember kids laughing at me, calling me stupid. There was a small group of people that I was friendly with, but we were all misfits. One of my closest friends had an inoperable brain tumor. Because of my problems coordinating my vision with my motor skills, I couldn’t participate in normal activities, such as sports or dance. By seventh grade, after years of working every day with my wonderful reading teacher, I was reading at almost grade level.

Then when we moved to Tennessee in my freshman year of high school, I felt like a new person. Nobody knew that I had learning difficulties. We moved to a rural community, so I got to be a top student, because I’d had the same classes in my Dallas private school the year before. In the tenth and eleventh grades, I was making A’s and B’s. I got a scholarship to college, where I was a straight-

My mom is the reason I’ve done well. She always believed in me, always felt I could make it; she never gave up. Plus, as I mentioned, I had an exceptional reading teacher. My goal was always to be an elementary school teacher, but, after teaching for years and realizing that a lot of the kids in my classes were not being accurately diagnosed, I decided to go to graduate school to get my Ph.D.

Today, in addition to teaching, I do private tutoring with children like me. First, I get kids to identify word sounds (phonemes) because children with dyslexia have a problem decoding the specific sounds of words. I’ll have the children identify how many sounds they hear in a word. . . .“Which sounds rhyme, which don’t?” . . . “If I change the word from cat to hat, what sound changes?” Most children naturally pick up on these reading cues. Kids with dyslexia need to have these skills directly taught.

Many children I tutor are in fourth or even sixth grade and have had years of feeling like a failure. They develop an attitude of “Why try? I’m going to fail anyway.” I can tell them that I’ve been there and that they can succeed. So I work on academic self-

216

Decoding the Meaning of the IQ Test

The first question we need to grapple with in looking at the meaning of the test relates to a measurement criterion called reliability. When people take a test thought to measure a basic trait, such as IQ, more than one time, their results should not vary. Imagine that your IQ score randomly shifted from gifted to average, year by year. Clearly, this test score would not tell us anything about a stable attribute called intelligence.

The good news is that, in elementary school, IQ test performance does typically remain stable (Ryan, Glass, & Bartels, 2010). In one amazing study, people’s scores remained fairly similar when they first took the test in childhood and then were retested more than a half-

This research tells us that we should never evaluate a child’s IQ during a family crisis such as divorce. But being reliable is only the first requirement. The test must be valid. This means it must predict what it is supposed to be measuring. Is the WISC a valid test?

If our predictor is academic performance, the answer is yes. A child who gets an IQ score of 130 will tend to perform well in the gifted class. A child whose IQ is 80 will probably need remedial help. But now we turn to the controversial question: Does the test measure genetic learning potential or biological smarts?

ARE THE TESTS A GOOD MEASURE OF GENETIC GIFTS? When we are evaluating children living in poverty (or boys and girls growing up in non-

An excellent argument that the environment weighs heavily in IQ comes from that remarkable century-

We also have newer research confirming that a poor life situation artificially limits IQ. For low-

Now, imagine that you are an upper-

DO IQ SCORES PREDICT REAL-

217

Psychologists debate the existence of “g.” Many strongly believe that the IQ test generally predicts intellectual capacities. They argue that we can use the IQ as a summary measure of a person’s cognitive potential for all life tasks (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994; Rushton & Jensen, 2005). Others believe that people have unique intellectual talents. There is no one-

Tantalizing evidence for “g” lies in the fact that people differ in the speed with which they process information (Brody, 2006; Rushton & Jensen, 2005). Intelligence test scores also correlate with various indicators of life success, such as occupational status. However, the problem is that the gateway to high-

One problem with believing that IQ tests offer a total X-

A high test score can produce its own problems. Suppose the student who told me his IQ was 140 decided he was so intelligent he didn’t have to open a book in my class. He might be in for a nasty surprise when he found out that what really matters is your ability to work. Or that person might worry: “I’d better not try in Dr. Belsky’s class because, if I do put forth effort and don’t get an A, I will discover that my astronomical IQ score was wrong.” (Recall the research in Chapter 6 that showed how telling elementary schoolers “you are smart” made them afraid to tackle challenging academic tasks.)

Even the firmest advocate of “g” would admit that some of us are marvelous mechanically and miserable at math, wonderful at writing but hopeless at reading maps.

Toward a Broader View of Intelligence

But if intelligence involves different abilities, such as Josiah’s mechanical talents (recall the introductory vignette), perhaps we should go beyond the IQ test to measure those skills in a broader way. Psychologists Robert Sternberg and Howard Gardner have devoted their careers to providing this broader view of what it means to be smart.

STERNBERG’S SUCCESSFUL INTELLIGENCE. Robert Sternberg (1984, 1996, 1997) has been a man on a mission. In hundreds of publications, this psychologist transformed the way we think about intelligence. Sternberg’s passion comes from the heart. He began school with a problem:

As an elementary school student, I failed miserably on the IQ tests. . . . Just the sight of the school psychologist coming into the classroom to give . . . an IQ test sent me into a wild panic attack. . . . You don’t need to be a genius to figure out what happens next. My teachers in the elementary school grades certainly didn’t expect much from me. . . . So I gave them what they expected. . . . Were the teachers disappointed? Not on your life. They were happy that I was giving them what they expected.

(Sternberg, 1997, pp. 17–

Sternberg actually believes that traditional intelligence tests do damage in the school environment. As I implied earlier, the relationship between IQ scores and schooling is somewhat bidirectional. Children who attend inferior schools, or who miss months of classroom work due to illness, perform more poorly on intelligence tests (Sternberg, 1997). Worse yet, Sternberg argues, when schools assign children to lower-

218

Most importantly, Sternberg (1984) believes that conventional intelligence tests are too limited. Although they do measure one type of intelligence, they do not cover the total terrain.

IQ tests, according to Sternberg, measure analytic intelligence. They test how well people can solve academic-

Brazilian street children who make their living selling flowers show impressive levels of practical intelligence. They understand how to handle money in the real world. However, they do poorly on measures of traditional IQ (Sternberg, 1984, 1997). Others, such as Winston Churchill, can be terrible scholars but flower after they leave their academic careers. Then, there are people who excel at IQ test taking and traditional schooling but fail abysmally once in the real world. Sternberg argues that to be successfully intelligent in life requires a balance of all three “intelligences.” (As a postscript, Sternberg recently added a fourth type of intellectual gift—

GARDNER’S MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES. Howard Gardner (1998) did not have Sternberg’s problem with intelligence tests:

As a child I was a good student and a good test taker . . . but . . . music . . . and the arts were important parts of my life. Therefore when I asked myself what optimal human development is, I became more convinced that [we] had to . . . broaden the definition of intelligence to include these activities, too.

(Gardner, 1998, p. 3)

Gardner is not passionately opposed to standard intelligence tests. Still, he believes that using the single IQ score is less informative than measuring children’s unique talents and gifts. (Gardner’s motto is: “Ask not how intelligent you are, but how are you intelligent?”) According to Gardner’s (2004, 2006) multiple intelligences theory, human abilities come in eight, and possibly nine, distinctive forms.

In addition to the verbal and mathematical skills measured by traditional IQ tests, people may be gifted in interpersonal intelligence, or understanding other people. Their talents may lie in intrapersonal intelligence, the skill of understanding oneself. They may be gifted in spatial intelligence, grasping where objects are arranged in space. (You might rely on a friend who is gifted in spatial intelligence to beautifully arrange the furniture in your house.) Some people have high levels of musical intelligence, or kinesthetic intelligence (the ability to use the body well), or naturalist intelligence (the gift for dealing with animals or plants and trees). There may even be an existential (spiritual) intelligence, too.

219

EVALUATING THE THEORIES. These perspectives on intelligence are exciting. Some of you may be thinking, “I’m gifted in practical or musical intelligence. I always knew there was more to being smart than school success!” But let’s use our practical intelligence to critique these approaches. Why did Gardner select these particular eight abilities and not others (Barnett, Ceci, & Williams, 2006; White, 2006)? Yes, parents may marvel at a 6-

We can also criticize Sternberg’s ideas. Is there such a thing as creative or practical intelligence apart from a particular field? Adopting the idea that there is a single “creative” intelligence might lead to the conclusion that Michelangelo would be a talented musician or that Mozart could beautifully paint the Sistine Chapel.

The bottom line is that neither Gardner nor Sternberg has developed replacements for our current IQ test. But this does not matter. Their mission is to transform the way schools teach (Gardner & Moran, 2006; Sternberg, 2010).

INTERVENTIONS: Lessons for Schools

Gardner’s theory has been embraced by teachers who understand that intelligence involves more than having traditional academic skills. However, to implement his ideas requires revolutionizing the way we structure education. Therefore, the main use of multiple intelligences theory has been in helping “nontraditional learners” succeed (Schirduan & Case, 2004). Here is how Mark, a dyslexic teenager, describes how he uses his spatial intelligence to cope with the maze of facts in history:

I’ll picture things; for example, if we are studying the French revolution . . . Louis the 16th. . . . I’ll have a picture of him in my mind [and I’ll visualize] the castle and peasants to help me learn.

(quoted in Schirduan & Case, 2004, p. 93)

Sternberg, being an experimentalist, has put his theory to rigorous test. Does instruction tailored to each different type of intelligence produce better achievement than teaching in the traditional way? Initial encouraging findings suggested yes (Sternberg, Torff, & Grigorenko, 1998). But when Sternberg’s research team carried out a massive intervention trial, assigning 7,702 fourth graders in 223 classrooms to either be taught according to his theory or several typical approaches, the outcome was inconsistent at best (Sternberg and others, 2014). So, while the concept of successful intelligence is intuitively appealing, it’s not clear that Sternberg’s ideas merit changing the way classrooms operate. How do classrooms operate?

Classroom Learning

The diversity of intelligences, cultures, and educational experiences at home is matched by the diversity of American schools. There are small rural schools and large urban schools, public schools and private schools, highly traditional schools where students wear uniforms and schools that teach to Gardner’s intelligences. There are single-

220

Can students thrive in every school? The answer is yes, provided schools have an intense commitment to student learning and teachers can excite students to learn. The rest of this chapter focuses on these challenges.

Examining Successful Schools

What qualities make a school successful? Insights come from surveying elementary schools that are beating the odds. These schools, while serving high fractions of economically disadvantaged children, have students who are thriving.

In the Vista School, located on a Native American reservation, for instance, virtually all the children are eligible for a free lunch. However, Vista consistently boasts dramatic improvements on statewide reading and math tests. According to Ms. Thompson, the principal, “Our job is not to make excuses for students, but just to give them every possible opportunity. At Vista, teachers refuse to dumb down the curriculum. We offer tons of high-

At Beacon Elementary School, two out of every three students exceed state-

Committed teachers, professional collaboration, and a mission to “deliver for all our kids” explains why a rural Florida elementary school, serving mainly low-

As Ms. Richards, the principal, explained: “We’ve got to improve to meet all kids needs. . . . That’s how we started and it didn’t turn into. . . a fix for one group, but how to make . . . everyone successful.” A special education teacher named Ms. Wood probably summed up this school’s teaching strategy best when she said, “We have ongoing conversations about challenging students . . . at our school . . . the meat of the curriculum is presented to everyone” (adapted from McLeskey, Waldron, & Redd, 2014, p. 63).

To summarize, successful schools set high standards. Teachers believe that every child can benefit from challenging, conceptual work. These schools offer an excess of nurture—

Now that we have the outlines for what is effective, let’s tackle the challenge every teacher faces: getting students eager to learn.

221

Producing Eager Learners

But to go to school in a summer morn,

O! it drives all joy away;

Under a cruel eye outworn,

The little ones spend the day

In sighing and dismay.

—William Blake, from “The Schoolboy” (1794)

Jean Piaget believed that the hunger to learn is more important than food or drink. Why then do children over the centuries lament, “I hate school”? The reason is that learning loses its joy when it becomes a requirement instead of an activity we choose to engage in for ourselves.

THE PROBLEM: AN EROSION OF INTRINSIC MOTIVATION. Developmentalists divide motivation into two categories. Intrinsic motivation refers to self-

Unfortunately, the learning activity you are currently engaged in falls into the extrinsic category. You know you will be tested on what you are reading. Worse yet, if you decided to pick up this book for an intrinsic reason—

Numerous studies show that when adults give external reinforcers for activities that are intrinsically motivating, children are less likely to want to perform those activities for themselves (Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008; Stipek, 1996). In one classic example, researchers selected preschoolers who were intrinsically interested in art. When they gave a “good player” award (an outside reinforcer) for the art projects, the children later showed a dramatic decline in their interest in doing art for fun (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973). This research makes sense of the question you may have wondered about: “Why, after taking that literature class, am I less interested in reading on my own?”

Young children enter kindergarten brimming with intrinsic motivation. When does this love affair with school turn sour? Think back to your childhood, and you will realize that enchantment wanes during early elementary school, when teachers provide those external reinforcers—

Then, as children enter concrete operations—

In sum, several forces explain why many children dislike school: School involves extrinsic reinforcers (grades). School learning, because it often involves rote memorization, is not intrinsically interesting. In school, children are not free to set their own learning goals. Their performance is judged by how they measure up to the rest of the class.

It is no wonder, therefore, that studies in Western nations document an alarming decline in intrinsic motivation as children travel through school (Katz, Kaplan, & Gueta, 2010; Spinath & Steinmayr, 2008). Susan Harter (1981) asked children to choose between two statements: “Some kids work really hard to get good grades” (referring to extrinsic motivation) or “Some kids work really hard because they like to learn new things” (measuring intrinsic motives). When she gave her measure to hundreds of California public school children, intrinsic motivation scores fell off from third to ninth grade.

222

Still, external reinforcers can be vital hooks that get us intrinsically involved. Have you ever reluctantly read a book for a class and found yourself captivated by the subject? Perhaps you enrolled in this course because it was required for graduation but are now so interested in the material that you want to make some aspect of developmental science your career. Given that extrinsically motivating activities are basic to school and life, how can we make them work best?

THE SOLUTION: MAKING EXTRINSIC LEARNING PART OF US. To answer this question, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan (1985, 2000) make the point that we engage in some types of extrinsic learning unwillingly: “I have to take that terrible anatomy course because it is a requirement for graduation.” We enthusiastically embrace other extrinsic tasks, which may not be inherently interesting, because we identify with their larger goal: “I want to memorize every bone of the body because that information is vital to my nursing career.” In the first situation, the learning activity is irrelevant. In the second, the task has become intrinsic because it is connected to our inner self. Therefore, the key to transforming school learning from a chore into a pleasure is to make extrinsic learning relate to children’s goals and desires.

The most boring tasks take on an intrinsic aura when they speak to children’s passions. Imagine, for instance, how a first grader’s motivation to sound out words might change if a teacher, knowing that student was captivated by dinosaurs, gave that boy the job of sounding out dinosaur names. Deci and Ryan believe that learning becomes intrinsic when it satisfies our basic need for relatedness (attachment). Think back to the discussion of schools that beat the odds. Imagine how motivated those children might be to learn to read when they understood that their success would make their beloved school proud. Finally, extrinsic tasks take on an intrinsic feeling when they foster autonomy, or offer choices of how to do our work (Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008; Ryan and others, 2006).

Studies around the globe suggest that when teachers and parents take away children’s autonomy—

Our need for autonomy explains why, as I suggested in the section on successful schools, assigning high-

But, in a national experiment, when certain school districts gave staff the chance to choose between several new programs and provided clear data about their effectiveness, teachers modified their behavior—

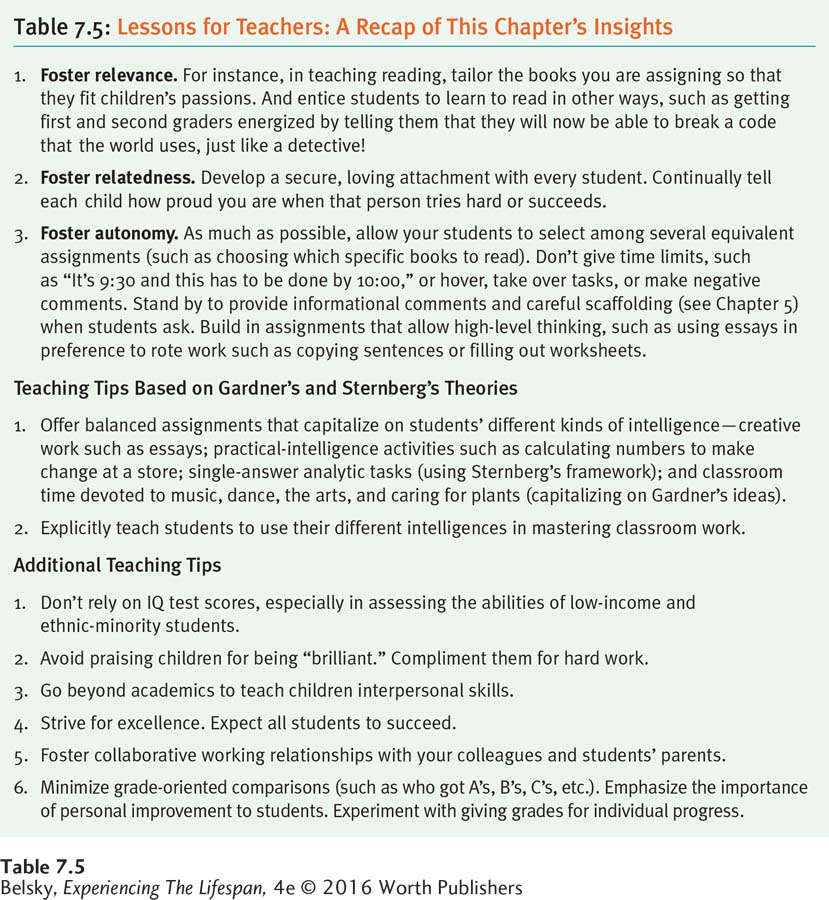

Table 7.5 summarizes these messages for teachers: Focus on relevance, enhance relatedness, and provide autonomy. The table also pulls together other teaching tips based on Gardner’s and Sternberg’s perspectives on intelligence and our look at what makes schools successful. Now, let’s conclude by touching briefly on that sea change in the U.S. public school landscape—

223

Hot in Developmental Science: The Common Core State Standards

At this point in the chapter, you are fully aware of the dispiriting problems plaguing U.S. schools. Affluent middle-

How can we change this scenario so that boys and girls—

Enter the Common Core State Standards. Rather than learning benchmarks differing in a crazy-

As of this writing, this landmark in education has been adopted in 45 states and the District of Columbia (Kornhaber, Griffith, and Tyler, 2014). But the revolution has miles to go (Rothman, 2014). Teachers need to learn how to teach using scaffolding and more Socratic (questioning, discussion-

224

Will school systems give teachers the space to creatively collaborate in how best to implement the Common Core, or will these guidelines be viewed as another airy set of autonomy-

The Common Core State Standards embody the equity and inclusiveness that we hope for when children arrive on the planet in this enlightened day and age. I hope this chapter has alerted you to generally think about development in a more enlightened, inclusive way. Child-

Tying It All Together

Question 7.7

If Devin, from an upper-

Both children will perform equally well on school readiness tests, but Adam will fall behind because he is likely to go to a poor-

quality kindergarten. Devin will outperform Adam on school readiness tests, and the gap will probably widen because Adam will go to a poor-

quality kindergarten.

b

Question 7.8

Malik hasn’t been doing well in school, and his achievement test scores have consistently been well below average for his grade. On the WISC, Malik gets an IQ score of 115. What is your conclusion?

Malik has a learning disability.

Question 7.9

You are telling a friend about the deficiencies of relying on a child’s IQ score. Pick out the two arguments you might make.

The tests are not reliable; children’s scores typically change a lot during the elementary school years.

The tests are not valid predictors of school performance.

As people have different abilities, a single IQ score may not tell us much about a child’s unique gifts.

As poor children are at a disadvantage in taking the test, you should not use the IQ scores as an index of “genetic school-

related talents” for low- income children.

c and d

Question 7.10

Josh doesn’t do well in reading or math, but he excels in music and dance, and he gets along with all kinds of children. In terms of Sternberg’s theory of successful intelligence, Josh is not good in __________, but he is skilled in __________ and __________. In terms of Gardner’s theory of __________, Josh is strong in which intelligences?

Analytic intelligence . . . creative intelligence and practical intelligence . . . multiple intelligences . . . Josh’s strengths are in musical, kinesthetic, and interpersonal intelligence.

Question 7.11

A principal of a school asks for tips to help her students with learning difficulties. Based on this section, you should advise (pick one): making the material simple/putting these children together in a special class/providing high-

You should advise giving these children high-

Question 7.12

(a) Define intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. (b) Give an example of a task in your life right now that is driven by each kind of motivation. (c) From reading the chapter, can you come up with some ways to make the unpleasant extrinsic tasks you do feel more intrinsic?

(a) Intrinsic motivation is self-