9.1 Setting the Context

Youth are heated by nature as drunken men by wine.

I would that there were no age between ten and twenty-three . . ., for there’s nothing in between but getting wenches with child, wronging the ancientry, stealing, fighting. . . .

William Shakespeare, The Winter’s Tale, Act III

As the quotations above illustrate, throughout history, wise observers of human nature have described young people as being emotional, hot-headed, and out of control. When, in 1904, G. Stanley Hall first identified a new life stage characterized by “storm and stress,” which he called “adolescence,” he was only echoing these timeless ideas. Moreover, as the mission of the young is to look at society in fresh, new ways, it makes sense that most cultures would view each new generation in ambivalent terms—praising young people for their energy and passion; fearing them as a menace and threat.

However, until fairly recently, young people never had years to explore life or rebel against society because they took on adult responsibilities at an early age. As you may remember from Chapter 1, adolescence only became a distinct stage of life in the United States during the twentieth century, when—for most children—going to high school became routine (Mintz, 2004; Modell, 1989; Palladino, 1996).

As this famous 1930s photograph of a migrant family traveling across the arid Southwest to search for California jobs illustrates, early in the Great Depression, there was no chance to go to high school and no real adolescence because children had, at a very young age, to work to help support their families.

© LOC/SSPL/The Image Works

Look into your family history and you may find a great-grandparent who finished high school or college. But a century ago, these events were fairly rare, as the typical U.S. child left school after sixth or seventh grade to find work (Mintz, 2004). Unfortunately, however, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, there was little work to find. Idle and at loose ends, young people took to roaming the countryside, angry, demoralized, and depressed. Alarmed by the situation, the federal government took action. At the same time that it instituted the Social Security system to provide for the elderly (to be discussed in Chapter 13), the Roosevelt administration implemented a national youth program to lure young people to school. The program worked. By 1939, 75 percent of all U.S. teenagers were attending high school.

High school boosted the intellectual skills of a whole cohort of Americans. But it produced a generation gap between these young people and their less educated, often immigrant parents and encouraged teens to spend their days together as an isolated, age-segregated group. Then, during the 1950s, when entrepreneurs began to target products to this new, lucrative “teen” market, we developed our familiar adolescent culture with its distinctive music and dress (Mintz, 2004; Modell, 1989). The sense of an adolescent society bonded together (against their elders) reached its height during the late 1960s and early 1970s. With “Never trust anyone over 30” as its slogan, the huge teenage baby boom cohort rejected the conventional rules related to marriage and gender roles and transformed the way we live our adult lives.

In this chapter, we will explore the experience of being adolescent in the contemporary developed world—a time in history when we expect teenagers to go to high school (and now college) and society insulates young people from adult responsibilities for a decade or more. First, I’ll be examining the cognitive abilities and emotional lives of teens. Then, I’ll chart how teenagers separate from their parents and relate to one another in groups. This chapter ends by touching on some issues that affect the millions of young people living in impoverished regions of the world, who can’t count on having a life stage called adolescence at all.

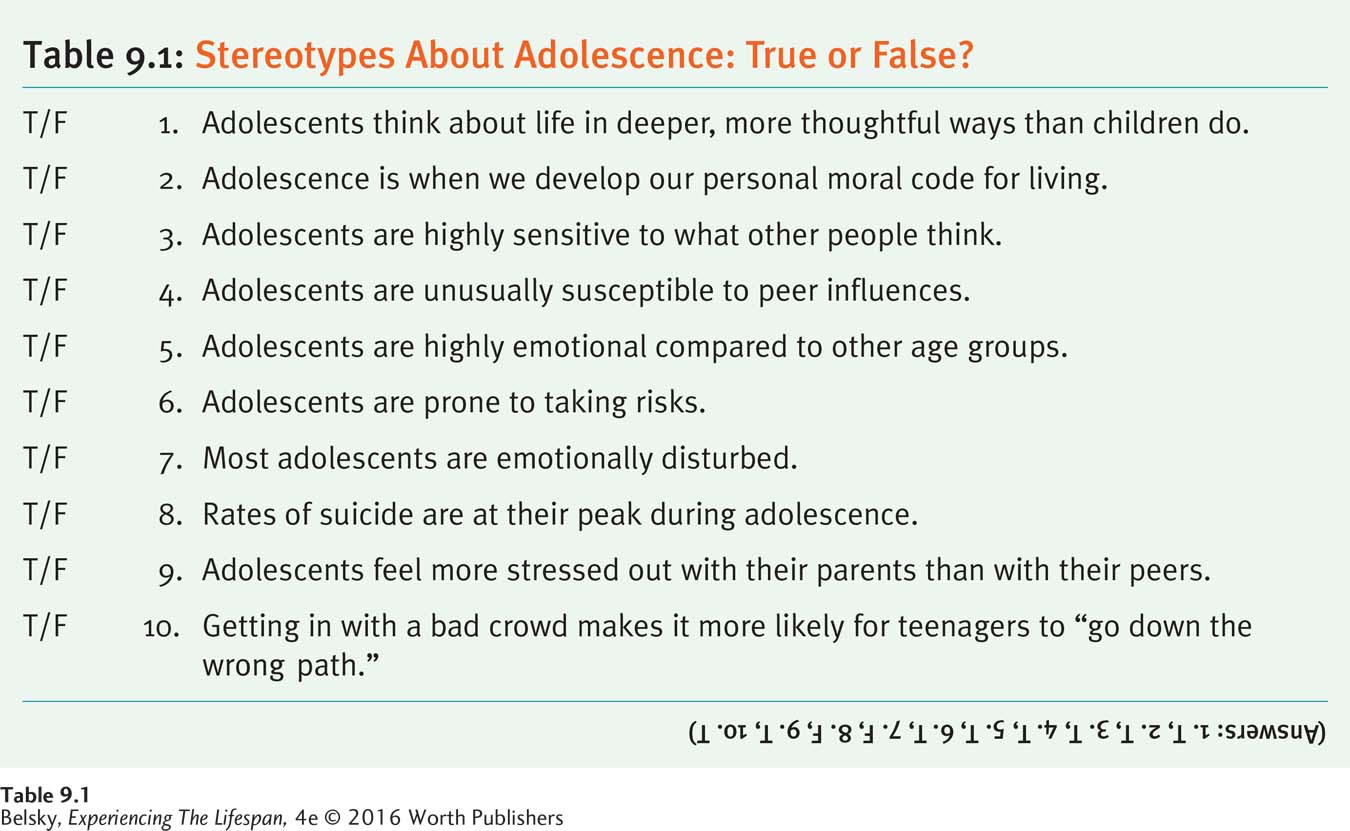

Before beginning your reading, you might want to take the “Stereotypes About Adolescence: True or False?” quiz in Table 9.1. In the following pages, I’ll be discussing why each stereotype is right or wrong.