9.3 Teenage Relationships

What exactly are teenager–

Separating from Parents

When I’m with my dad fishing, or when my family is just joking around at dinner—

In their original experience-

280

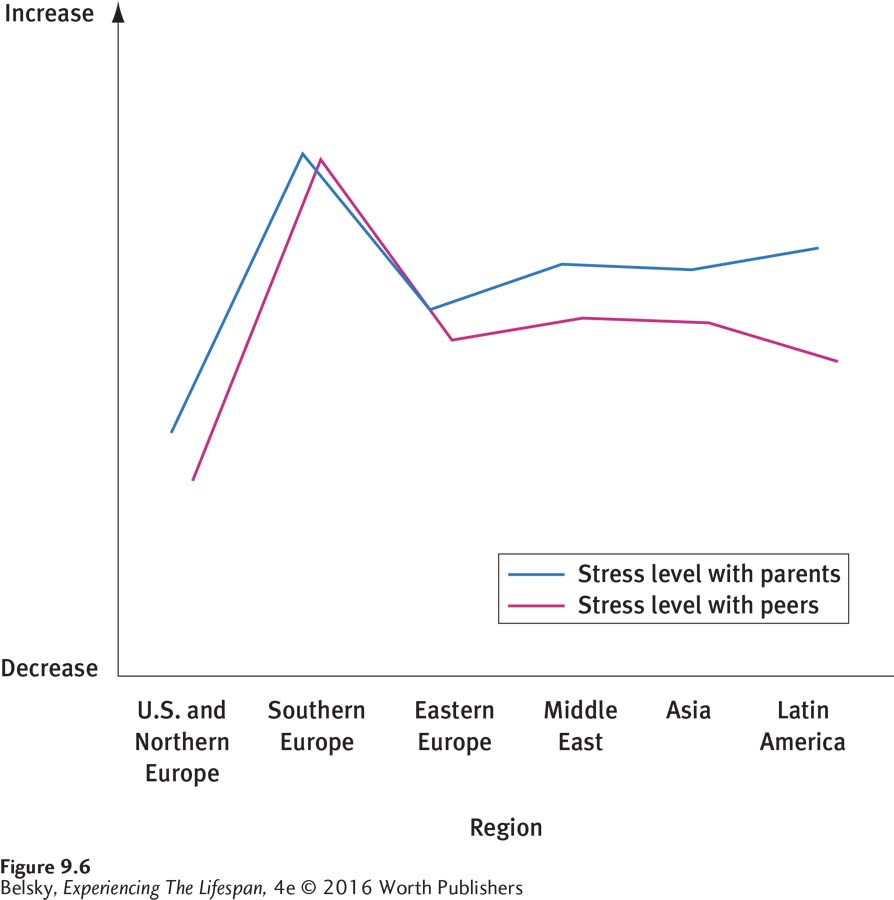

This tendency to lock horns with our parents seems built into the adolescent experience, as the global poll illustrated in Figure 9.6 shows. Notice that, while the magnitude of the gap differs from nation to nation, teens worldwide typically rank stress in the parent–

The Issue: Pushing for Autonomy

Why does family life produce such teenage pain? As developmentalists point out, if our home life is good, our family provides our cocoon. Home is the place where we can relax, be ourselves, and feel completely loved. However, in addition to being our safe haven, parents must be a source of pain. The reason is that parents’ job is both to love us and to limit us. When this parental limiting function gets into high gear, teenage distress becomes acute.

What do teenagers and their parents argue about? This global poll offers insights into unique cultural parenting priorities in different regions of the world (Persike & Seffige-

Perhaps, because it’s especially crucial in these collectivist societies to marry within “one’s own group,” in the Middle East, micromanaging peer relationships is a major stress (“My parents won’t let me see the friends I want!”). In southern Europe, where children still live with their parents well into their late twenties and early thirties, dependency and general parent–

But it should come as no surprise that the underlying issue in every nation centers around independence (“Why can’t I do what I want? You have too many rules!”). Moreover, the most intense clashes occur just when peer group popularity pressures reach their height—

The Process: Exploring the Dance of Autonomy

281

Actually, parent–

How does the dance of autonomy unfold? Based on periodically asking teens questions—

As it turns out, children first initiate the push for independence by becoming secretive and distant in their early teens. But, parents only respond by steadily granting their children much more freedom beginning after age 15.

Why is mid-

Even the major social markers of independence at around age 16 or 17 eliminate sources of family strain. Think about how getting your first job, or your license, removed an important area of family conflict. You no longer had to ask your parents for every dime or rely on mom or dad to get around.

These adult landmarks put distance between parents and teenagers in the most basic, physical way. The experience-

So the process of separating from our families makes it possible to have a more harmonious family life. The delicate task for parents, as I suggested earlier, is to give teens space to explore their new, adult selves and still remain closely involved (Steinberg, 2001). One mother of a teenager explained what ideally should happen, when she said: “I don’t treat her like a young child anymore, but we’re still very, very close. Sort of like a friendship, but not really, because I’m still in charge. She’s my buddy” (quoted in Shearer, Crouter, & McHale, 2005, p. 674).

This quotation brings up a fascinating gender difference in the parent–

Cultural Variations on a Theme

282

My parents won’t let me date anyone who isn’t Hindi—

In individualistic societies, we strive for parent–

As researchers point out, with immigrant adolescents, the normal impulse to separate can be exacerbated by issues relating to acculturation (Kim & Park, 2011; Park and others, 2010; Wu & Chao, 2011; Kim and others, 2013). Teens want to become “real” Americans. They may think: “My parents have old-

Family pressures, as you saw in the example above, present special hurdles for immigrant teens. Straddling two cultures can upend the normal parent–

Given these strains, are immigrant teens at risk for poor parent–

So, knowing that one’s parents made a rare sacrifice (“giving up their happiness and moving for my future”) can create unusually close parent–

This quotation may explain a phenomenon called the immigrant paradox. Despite coping with an overload of stresses (Cho & Haslam, 2010), many immigrant children living in poverty do better than their peers (van Geel & Vedder, 2011). But like all children, immigrant teens take different paths—

Connecting in Groups

Go to your local mall and watch sixth and seventh graders hanging out to get a firsthand glimpse of the group passion that takes over during the early teens. Now that we understand peer group’s potentially destructive effects, let’s turn to the vital positive functions pre-

Defining Groups by Size: Cliques and Crowds

283

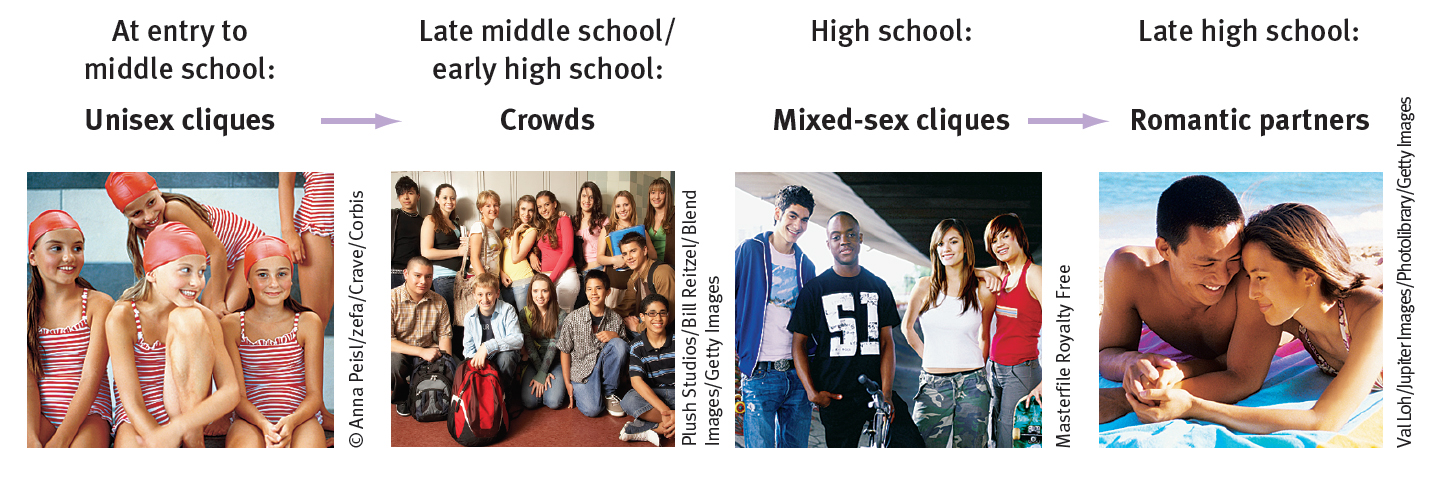

Developmentalists classify teenage peer groups into categories. Cliques are intimate groups having a membership size of about six. Your group of closest friends would constitute a clique. Crowds are larger groupings. Your crowd comprises both your best buddies and a more loose-

In a l960s observational study in Sydney, Australia, one researcher found that these groups serve a crucial purpose: They are the vehicles that convey teenagers to relationships with the opposite sex (Dunphy, 1963).

As you can see in the photos in Figure 9.7, children enter their pre-

The crowd is an ideal medium to bridge the gap between the sexes because there is safety in numbers. Children can still be with their own gender while they are crossing into that “foreign” land. Gradually, out of these large-

You might be surprised to know that the progression outlined in this 50-

What Is the Purpose of Crowds?

Crowds have other functions. They allow teenagers to connect with people who share their values. Just as we select friends who fit our personalities, we gravitate to the crowd that fits our interests. We disengage from a crowd when its values diverge from ours. As one academically focused teenager lamented: “I see some of my friends changing. . . . They are getting into parties and alcohol. . . . We used to be good friends . . . and now, I can’t really relate to them . . . . That’s kind of sad” (quoted in Phelan, Davidson, & Yu, 1998, p. 60).

284

Crowds, actually, serve as a roadmap, allowing teens to connect with “our kind of people” in an overwhelming social world (Smetana, Campione-

What Are the Kinds of Crowds?

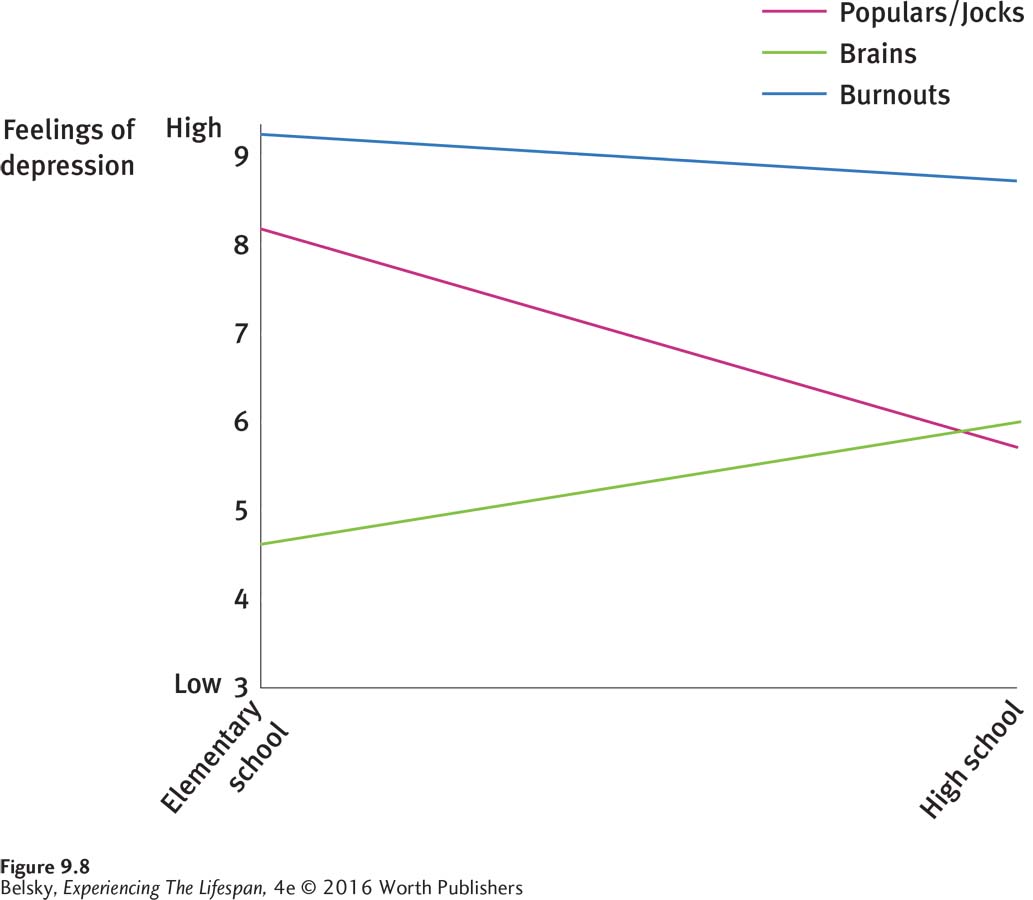

In affluent societies, there is consistency in the major crowd categories. The intellectuals (also called brains, nerds, grinds, or geeks), the popular kids (also known as hotshots, preppies, elites, princesses), the deviants (burnouts, dirts, freaks, druggies, potheads), and a residual type (Goths, alternatives, grubs, loners, independents) appear in high schools throughout the West (Sussman and others, 2007).

How much mixing occurs between different crowds? Although teens do straddle different groups (Lonardo and others, 2009), adolescents tend to have friends in similar status crowds. So a popular boy, as suggested earlier in the chapter, associates with the popular kids. He shuns the socially more marginal groups, such as the deviants (bad kids) or nerdy brains. Moreover, as being brainy and especially advertising that you work for high grades can go against the group norms, intellectuality does not gain teenagers kudos in the peer world, at least in the standard public school (Sussman and others, 2007).

A study tracking children’s self-

Finally, notice that the teenagers in the deviant burnout group tend to be most depressed before adolescence and stay at the low end of the happiness continuum in high school (see also Heaven, Ciarrochi, & Vialle, 2008). We already know that failing in middle childhood predicts gravitating toward groups of “bad” peers. Now, let’s explore why joining that bad crowd makes a teenager even more likely to fail.

“Bad Crowds”

The classic defense that parents give for a teenager’s delinquent behavior is, “My child got involved with a bad crowd.” Without ignoring the principle of selection (birds of a feather flock together), there are powerful reasons why bad crowds do cause kids to do bad things.

For one thing, as we know, teenagers are incredibly swayed by their peers. Moreover, each group has a leader, the person who most embodies the group’s goals. So, if a child joins the brains group, his school performance is apt to improve because everyone is jockeying for status by competing for grades (Cook, Deng, & Morgano, 2007; Molloy, Gest, & Rulison, 2011). However, in delinquent groups, the pressure is to model the most antisocial member. Therefore, the activities of this most acting-

285

So, in the same way you felt compelled to jump into the icy water at camp when the bravest of your bunkmates took the plunge, if one group member begins selling guns or drugs, the rest must follow the leader or be called “chicken.” Moreover, when children compete for status by getting into trouble, this creates ever-

Combine this principle with the impact of just being in a group. When young people get together, a group high occurs. Talk gets louder and more outrageous. People act in ways that would be unthinkable if they were alone. From rioting at rock concerts to being in a car with your buddies during a drive-

By videotaping groups of boys, developmentalists have documented the deviancy training, or socialization into delinquency, that occurs as a function of simply talking with friends in a group (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999; Rorie and others, 2011). The researchers find that at-

286

The lure of entering an antisocial peer group is especially strong for at-

In middle-

Society’s Nightmare Crowd: Teenage Gangs

The gang, a close-

Gangs provide teenagers with status. They offer physical protection in dangerous neighborhoods (Shelden, Tracy, & Brown, 1997). When young people have few options for making it in the conventional way, gangs offer a pathway to making a living (for example, by selling drugs or stealing). So, in dangerous neighborhoods, what starts as time-

This suggests that moving inner city children to middle-

A Note on Adolescence Worldwide

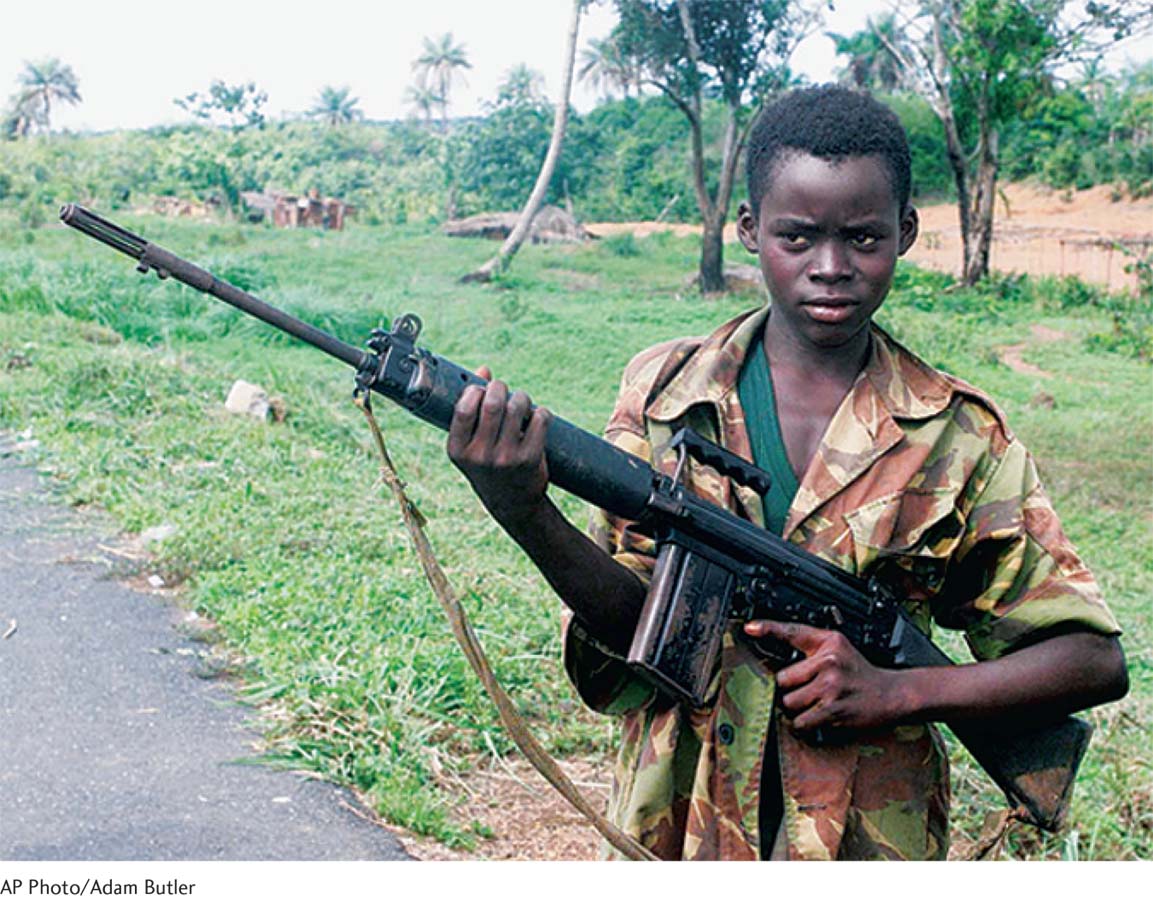

It also takes a kinder, gentler society for adolescence to exist. So, children growing up in impoverished areas of the world are less apt to have this extra decade insulated from adult life. Unfortunately, adolescence has been eliminated for the approximately 1 million children who enter the sex trade every year (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 2002). Some of these boys and girls are street children, living in gangs in cities in Latin America and Southeast Asia. Or destitute parents may sell their daughters into the sex industry in order for the family to survive (Gajic-

287

Adolescence has been eliminated for the hundreds of thousands of child soldiers. Many combatants in the poorest regions of the globe are teenage boys. Some are coerced into fighting as young as age 10 or 8 (Child Soldiers Global Report, 2008; UNICEF, 2002a).

Yes, many teenagers in the world’s affluent areas are flourishing. But children in the least-

How can you personally flourish during your adult years? Stay tuned for research relating to this question in the next part of the book.

Tying It All Together

Question 9.8

Chris and her parents are arguing again. Based on this chapter, at what age might arguments between Chris and her parents be most intense? Around what age would Chris’s parents have begun to seriously loosen their rules? Choose between ages 12, 16, and 19.

At age 12, the arguments would be most intense; by age 16, Chris’s parents would be giving her much more freedom

Question 9.9

Your niece Heather hangs around with a small group of girlfriends. You see them at the mall giggling at a group of boys. According to the standard pattern, what is the next step?

Heather and her friends will begin going on dates with the boys.

Heather and her clique will meld into a large heterosexual crowd.

Heather and her clique will form another small clique composed of both girls and boys.

b

Question 9.10

Mom #1 says, “Getting involved with the ‘bad kids’ makes teens get into trouble.” Mom #2 disagrees: “It’s the kid’s personality that causes him to get into trouble.” Mom #3 says, “You both are correct—

Mom #3 is correct.

Question 9.11

You want to intervene to help prevent at-

Checklist: (1) Is this child unusually aggressive? (2) Is he failing at school and being rejected by the mainstream kids? (3) Does this child have poor relationships with his parents? (4) Does he live in a dangerous community, or a risk-