Families and Children

No one doubts that genes affect personality as well as ability, that peers are vital, and that schools and cultures influence what, and how much, children learn. Some have gone farther, suggesting that genes, peers, and communities have so much influence that parenting has little impact—

Shared and Nonshared Environments

Many studies have found that children are much less affected by shared environment (influences that arise from being in the same environment, such as two siblings living in one home, raised by their parents) than by nonshared environment (e.g., the experiences in the school or neighborhood that differ between one child and another).

417

Most personality traits and intellectual characteristics can be traced to genes and nonshared environments, with little left over for the shared influence of being raised together. Even psychopathology, happiness, and sexual orientation (Burt, 2009; Långström et al., 2010; Bartels et al., 2013) arise primarily from genes and nonshared environment.

Since many research studies find that shared environment has little impact, could it be that parents are merely caretakers, necessary for providing basics (food, shelter), harmful when abusive, but inconsequential in their daily restrictions, routines, and responses? Could it be that it doesn’t matter much if parents enforce a set bath and bedtime, or if the parents let the child wash and sleep when he wishes? If a child becomes a murderer or a hero, maybe that is genetic and non-

Recent findings, however, reassert parent power. The analysis of shared and nonshared influences was correct, but the conclusion was based on a false assumption. Siblings raised together do not share the same environment.

Especially for Scientists How would you determine whether or not parents treat all their children the same?

Proof is very difficult when human interaction is the subject of investigation, since random assignment is impossible. Ideally, researchers would find identical twins being raised together and would then observe the parents’ behavior over the years.

For example, if relocation, divorce, unemployment, or a new job occurs in a family, the impact on each child depends on the child’s age, genes, resilience, and gender. Moving to another town upsets a school-

The variations above do not apply for all siblings: Differential susceptibility means that one child is more affected, for better or worse, than another (Pluess & Belsky, 2010). When siblings are raised together, all experiencing the same dysfunctional family, each children’s genes, age, and gender may lead one child to become antisocial, another to be pathologically anxious, and a third to be resilient, capable, and strong (Beauchaine et al., 2009). Further, parents do not treat each child the same, even when the children look identical, as the following makes clear.

a view from science

“I Always Dressed One in Blue Stuff …”

To separate the effects of genes and environment, many researchers have studied twins. As you remember from Chapter 3, some twins are dizygotic, with only half of their genes in common, and some are monozygotic, identical in all their genes. It was assumed that children growing up with the same parents would have the same nurture, so that if dizygotic twins were less alike than monozygotic twins (and they often are), their differences must be genetic. However, if one monozygotic twin was unlike the other, that must be the result of nonshared environment (i.e., non-

That logical idea was the basis for research that found that genes and nonshared environment had a greater effect on twins than shared family environment, and, by extension, on everyone. Comparing monozygotic and dizygotic twins continues to be a useful research strategy. Recently it led to interesting conclusions about the interplay of nature and nurture in topics from food preferences of 3-

However, those research conclusions are now tempered by another finding: Siblings raised in the same households do not necessarily share the same home environment. A seminal study in this regard occurred with twins in England.

An expert team of scientists compared 1,000 sets of monozygotic twins reared by their biological parents (Caspi et al., 2004). Obviously, the pairs were identical in genes, sex, and age. The researchers asked the mothers to describe each twin. Descriptions ranged from very positive (“my ray of sunshine”) to very negative (“I wish I never had her…. She’s a cow, I hate her”) (quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 153). Many mothers noted personality differences between their twins. For example, one mother said:

Susan can be very sweet. She loves babies … she can be insecure … she flutters and dances around…. There’s not much between her ears…. She’s exceptionally vain, more so than Ann. Ann loves any game involving a ball, very sporty, climbs trees, very much a tomboy. One is a serious tomboy and one’s a serious girlie girl. Even when they were babies I always dressed one in blue stuff and one in pink stuff.

[quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 156]

418

Some mothers rejected one twin but not the other:

He was in the hospital and everyone was all “poor Jeff, poor Jeff” and I started thinking, “Well, what about me? I’m the one’s just had twins. I’m the one’s going through this, he’s a seven-

[quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 156]

This mother later blamed Jeff for favoring his father: “Jeff would do anything for Don but he wouldn’t for me, and no matter what I did for either of them [Don or Jeff] it wouldn’t be right” (p. 157). She said Mike was much more lovable.

The researchers measured personality at age 5 (assessing, among other things, antisocial behavior as reported by kindergarten teachers) and then measured each twin’s personality two years later. They found that if a mother was more negative toward one of her twins, that twin became more antisocial, more likely to fight, steal, and hurt others at age 7 than at age 5, unlike the favored twin.

These researchers acknowledge that many other nonshared factors—

Family Structure and Family Function

Family structure refers to the legal and genetic connections among related people. Legal connections may be marriage or adoption; genetic connections may be from parent to child, or more broadly as between cousins, or grandparents and grandchildren, or even between great aunts and second cousins.

Family function refers to how the people in a family care for each other: Some families function well, others are dysfunctional.

Function is more important than structure; everyone needs family love and encouragement, which can come from parents, grandparents, siblings, or any other relative. Beyond that, people’s needs differ depending on how old they are: Infants need responsive caregiving, teenagers need guidance, young adults need freedom, the aged need respect.

The Needs of Children in Middle Childhood

What do school-

Physical necessities. Although 6-

to 11- year- olds eat, dress, and go to sleep without help, families provide food, clothing, and shelter. Ideally, children live in a household where adults meet their basic needs. Learning. These are prime learning years: Families support, encourage, and guide education.

Self-

respect. Because children at about age 6 become much more self- critical and socially aware, families provide opportunities for success (in academic pursuits, in sports, in the arts, or whatever). Peer relationships. Families choose schools and neighborhoods with friendly children and then arrange play dates, group activities, overnights, and so on.

Harmony and stability. Families provide protective, predictable routines in a home that is a safe, peaceful haven.

419

The final item on the list above is especially crucial in middle childhood: Children cherish safety and stability, they do not like change (Turner et al., 2012). Ironically, many parents move from one neighborhood or school to another during these years. Children who move frequently are significantly harmed, academically and psychologically, but resilience is possible (Cutuli et al., 2013).

The problems arising from instability are evident for U.S. children in military families. Enlisted parents tend to have higher incomes, better health care, and more education than do civilians from the same backgrounds. But they have one major disadvantage: They move.

Military children have more emotional problems and lower school achievement than do their peers from civilian families. In reviewing earlier research, a scientist reports “[m]ilitary parents are continually leaving, returning, leaving again… school work suffers, more for boys than for girls, …and that reports of depression and behavioral problems go up when a parent is deployed” (Hall, 2008, p. 52).

About half the military personnel on active duty have children, and many of their children learn to cope with the stresses they experience (Russo & Fallon, 2014). To help them, the U.S. military has instituted special programs to help children whose parents are deployed. Caregivers of such children are encouraged to avoid changes in the child’s life: no new homes, new rules, or new schools (Lester et al., 2011). Similar concerns arise when a deployed parent comes home: He or she is welcomed, of course, but sometimes return signifies changes in the child’s life, and that is difficult.

On a broader level, children who are repeatedly displaced because of storms, fire, war, and the like are particularly likely to suffer in middle childhood. At this age, many children try to protect their parents by not telling them how distressed they are, but the data reveal that moving from place to place impairs a child’s health and school learning (Masten, 2014).

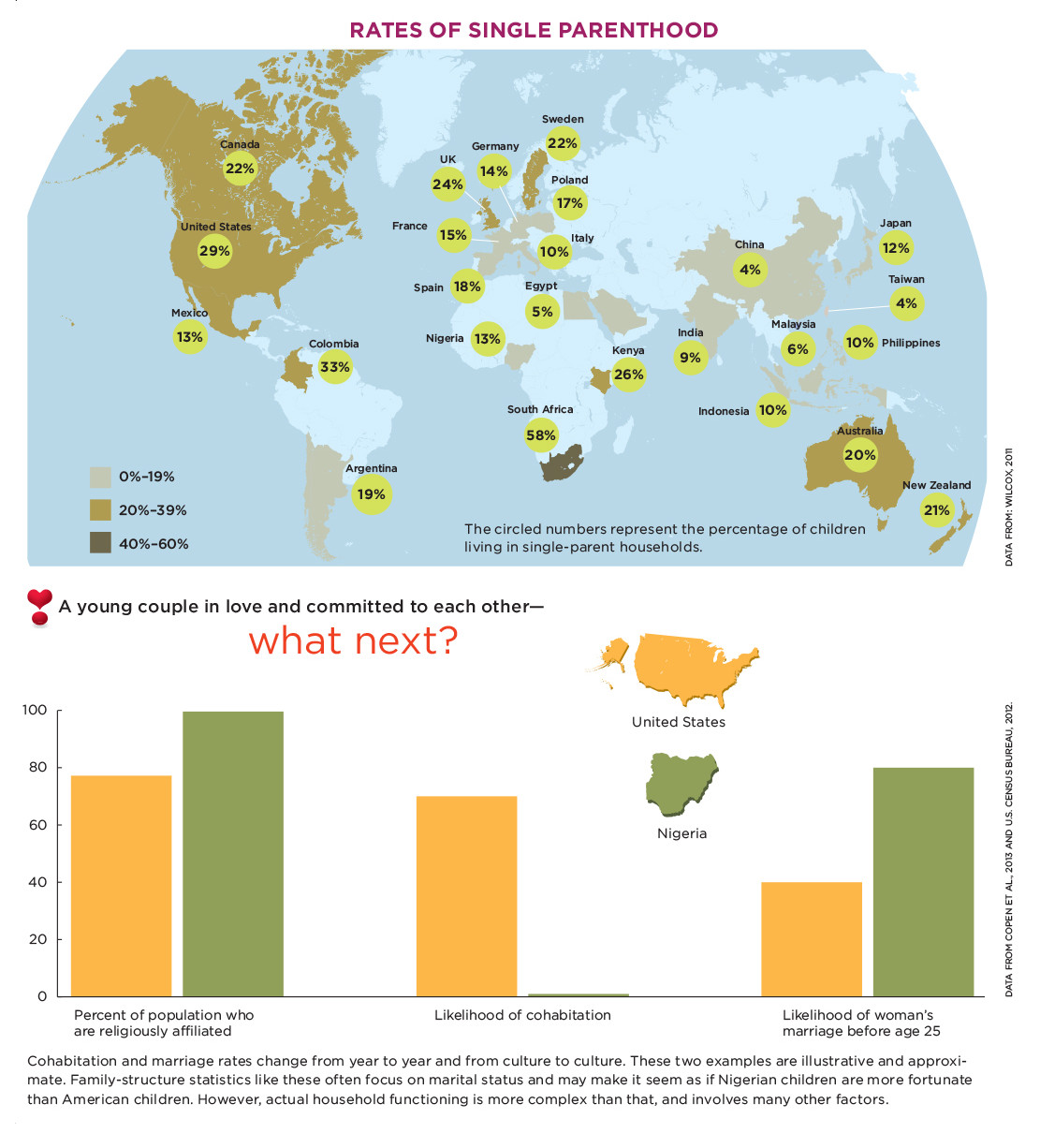

Diverse Structures

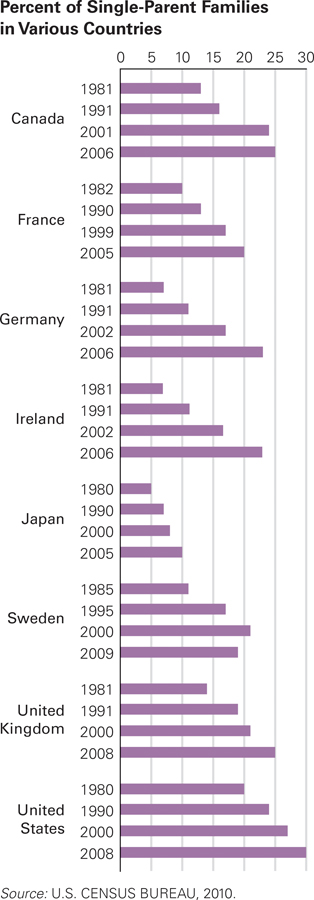

Worldwide today, there are more single-

Single Parents A rising percentage of all households with children are headed by a single parent. In some countries, many households are headed by two unmarried parents, a structure not shown here. With the exception of Ireland, whose data are from family-

Such diversity should be acknowledged but not exaggerated. Almost two-

Rates of single-

An extended family includes relatives in addition to parents and children. Usually the additional persons are grandparents, sometimes uncles, aunts, or cousins of the child.

The crucial distinction between types of families is based on who lives together in the same household. Many so-

420

In many nations, the polygamous family (one husband with two or more wives) is an acceptable family structure. Generally in polygamous families, income per child is reduced, and education, especially for the girls, is limited (Omariba & Boyle, 2007). Polygamy is rare—

421

a view from science

Divorce

Scientists try to provide analysis and insight based on empirical data (of course), but the task goes far beyond reporting facts. Regarding divorce, thousands of studies and several opposing opinions need to be considered, analyzed, and combined—

Among the facts that need analysis are these:

The United States leads the world in the rates of marriage, divorce, and remarriage, with almost half of all marriages ending in divorce.

Single parents, cohabiting parents, and stepparents sometimes provide good care, but children tend to do best in nuclear families with married parents.

Divorce often impairs children’s academic achievement and psychosocial development for years, even decades.

Each of these is troubling. Why does this occur? The problem, Cherlin (2009) contends, is that U.S. culture is conflicted: Marriage is idolized, but so is personal freedom. As a result, many people assert their independence by marrying without consulting their parents or community. Then, child care often becomes overwhelming and family support is lacking.

Because the United States does not provide paid parental leave or public child care, marriages become strained. Divorce seems to be the solution. However, because marriage remains the ideal, divorced adults blame their former mate or their own poor decisions, not the institution or the society.

Consequently, they seek another marriage, which may lead to another divorce. (Divorced people are more likely to remarry than single people their age are to marry, but second marriages fail more often than first marriages.) Repeated transitions allow personal freedom for the adults but harm the children.

This leads to a related insight. Cherlin suggests that the main reason children are harmed by divorce—

Scholars now describe divorce as a process, with transitions and conflicts before and after the formal event (H. S. Kim, 2011; Putnam, 2011). As you remember, resilience is difficult when the child must contend with repeated changes and ongoing hassles—

Beyond analysis and insight, the other task of developmental science is to provide practical suggestions. Most scholars would agree with the following:

Marriage commitments need to be made slowly and carefully, to minimize the risk of divorce. It takes time to develop intimacy and commitment.

Once married, couples must work to keep the relationship strong. Often happiness dips after the birth of the first child. New parents need to do together what they love—

dancing, traveling, praying, whatever. Divorcing parents need to minimize transitions and maintain a child’s relationships with both parents. A mediator—

who advocates for the child, not for either parent— may help. In middle childhood, schools can provide vital support. Routines, friendships, and academic success may be especially crucial when a child’s family is chaotic.

This may sound idealistic. However, another scientist, who has also studied divorced families for decades, writes:

Although divorce leads to an increase in stressful life events, such as poverty, psychological and health problems in parents, and inept parenting, it also may be associated with escape from conflict, the building of new more harmonious fulfilling relationships, and the opportunity for personal growth and individuation.

[Hetherington, 2006, p. 204]

Not every parent should marry, not every marriage should continue, and divorce does not harm every child. However, every child benefits if families fulfill all five needs of school-

422

Connecting Family Structure and Function

How a family functions is more important for the children than the structure of their family. That does not make structure irrelevant. The two are related; structure influences—

Two-Parent Families

On average, nuclear families function best; children in the nuclear structure tend to achieve better in school with fewer psychological problems. A scholar who summarized dozens of studies concludes: “Children living with two biological married parents experience better educational, social, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes than do other children” (Brown, 2010, p. 1062). Why? Does this mean that everyone should marry before they have a child, and then stay married? Not necessarily. The case for nuclear families is not as strong as it appears. Some benefits are correlates, not causes.

Education, earning potential, and emotional maturity all make it more likely that people will marry, have children, stay married, and establish a nuclear family. For example, first-

Thus, brides and grooms may have personal assets before they marry and become parents. That means that the correlation between child success and married parents occurs partly because of who marries, not because of the wedding. For some unmarried mothers, making a legal, binding commitment would actually render them less able to devote the attention and love that their child needs.

Income also correlates with family structure. Usually, if everyone can afford it, relatives live independently, apart from the married couple. That means that, at least in the United States, an extended family suggests that someone is financially dependent.

423

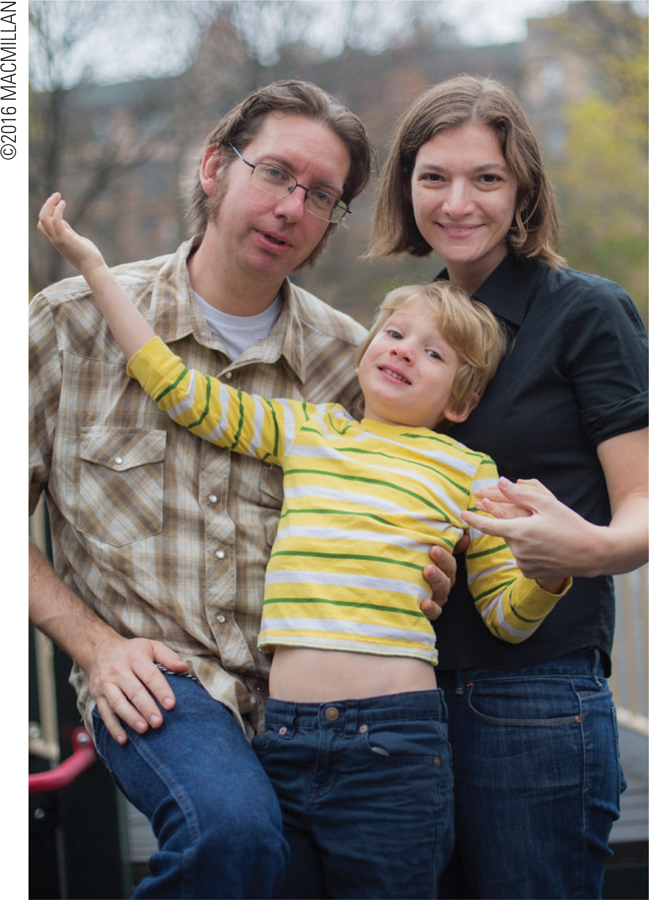

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

A Wedding, or Not? Family Structures Around the World

Children fare best when both parents actively care for them every day. This is most likely to occur if the parents are married, although there are many exceptions. Many developmentalists now focus on the rate of single parenthood, shown on this map. Some single parents raise children well, but the risk of neglect, poverty, and instability in single-

424

These two factors—

The parental alliance is important in every nation, but its influence is particularly apparent in Russia, where recent economic upheaval has reduced the male average life span from age 64 in 1985 to 59 in 2000. Those most at risk for a premature death are single men, who have higher rates of depression and alcoholism. The husband/father role leads men to take better care of themselves, so they can care for their children (Ashwin & Isupova, 2014). (Developmental Link: The parental alliance was first discussed in Chapter 4.)

Shared parenting also decreases the risk of child maltreatment and makes it more likely that children will have someone to read to them, check their homework, invite their friends over, buy them new clothes, and save for their education. Of course, having two married parents does not guarantee an alliance. One of my students wrote:

My mother externalized her feelings with outbursts of rage, lashing out and breaking things, while my father internalized his feelings by withdrawing, being silent and looking the other way. One could say I was being raised by bipolar parents. Growing up, I would describe my mom as the Tasmanian devil and my father as the ostrich, with his head in the sand…. My mother disciplined with corporal punishment as well as with psychological control, while my father was permissive. What a pair.

[C., 2013]

This student never experienced a well-

One consequence: When children reach “the age of majority” (usually 18) and fathers are no longer legally responsible for their children, many divorced or unmarried fathers stop child support. Unfortunately, most emerging adults need substantial funds if they want to attend college or live independently, so a long-

The lack of financial support for older adolescents is not simply because two-

Stepfathers tend to spend very little time caring for their stepchildren, even when they live together (Kalil et al., 2014). When they grow up, their children are more likely to live farther from either father than children from nuclear families are (Seltzer et al., 2013). The parental alliance is weaker in such families in childhood, and that becomes a weaker family alliance lifelong.

425

Adoptive and same-

All three family types (step-

Further, harmony is more difficult in stepfamilies (Martin-

Children who gain a stepparent may be angry or sad; for both reasons, they often act out (for example, fight with friends, fail in school, refuse to follow household rules). That causes disagreements for their newly married parents, who often have opposite strategies for child-

Further, disputes between half-

Finally, the grandparent family is often idealized, but reality is much more complex. If a household has grandparents and parents, often conflicts arise, and sometimes the grandparents are care-

But the grandparents usually do not benefit. On average, grandparents in skipped-

Despite all these problems, skipped-

Single-Parent Families

Especially for Single Parents You have heard that children raised in one-

Do not get married mainly to provide a second parent for your child. If you were to do so, things would probably get worse rather than better. Do make an effort to have friends of both sexes with whom your child can interact.

On average, the single-

426

Rates of single parenthood and single grandparenthood are far higher among African Americans than other ethnic groups. This increases the neighborhood acceptance but does not lighten the burden. If a single parent is depressed (and many are), that compounds the problem. The following case is an example.

a case to study

How Hard Is It to Be a Kid?

Neesha’s fourth-

The counselor spoke to Neesha’s mother, Tanya, a depressed single parent who was worried about paying rent on the tiny apartment where she had moved when Neesha’s father left three years earlier. He lived with his girlfriend, now with a new baby. Tanya said she had no problems with Neesha, who was “more like a little mother than a kid,” unlike her 15-

Tyrone was recently beaten up badly as part of a gang initiation, a group he considered “like a family.” He was currently in juvenile detention, after being arrested for stealing bicycle parts. Note the nonshared environment here: Although the siblings grew up together, when their father left, 12-

The school counselor spoke with Neesha.

Neesha volunteered that she worried a lot about things and that sometimes when she worries she has a hard time falling asleep…. she got in trouble for being late so many times, but it was hard to wake up. Her mom was sleeping late because she was working more nights cleaning offices…. Neesha said she got so far behind that she just gave up. She was also having problems with the other girls in the class, who were starting to tease her about sleeping in class and not doing her work. She said they called her names like “Sleepy” and “Dummy.” She said that at first it made her very sad, and then it made her very mad. That’s when she started to hit them to make them stop.

[Wilmshurst, 2011, pp. 152–

Neesha was coping with poverty, a depressed mother, an absent father, a delinquent brother, and classmate bullying. She seemed to have been resilient—

The school principal received a call from Neesha’s mother, who asked that her daughter not be sent home from school because she was going to kill herself. She was holding a loaded gun in her hand and she had to do it, because she was not going to make this month’s rent. She could not take it any longer, but she did not want Neesha to come home and find her dead…. While the guidance counselor continued to keep the mother talking, the school contacted the police, who apprehended [the] mom while she was talking on her cell phone…. The loaded gun was on her lap…. The mother was taken to the local psychiatric facility.

[Wilmshurst, 2011, pp. 154–

Whether Neesha will be able to cope with her problems depends on whether she can find support beyond her family. Perhaps the school counselor will help:

When asked if she would like to meet with the school psychologist once in a while, just to talk about her worries, Neesha said she would like that very much. After she left the office, she turned and thanked the psychologist for working with her, and added, “You know, sometimes it’s hard being a kid.”

[Wilmshurst, 2011, p. 154]

Family structure encourages or undercuts healthy function, but many parents and communities overcome structural problems to support their children. Contrary to the averages, thousands of nuclear families are destructive, thousands of stepparents provide excellent care, and thousands of single-

427

Culture is always influential. In contrast to data from the United States, a study in the slums of Mumbai, India, found rates of psychological disorders among school-

Overall, single parents are much less common in many nations than in the United States, but in both these studies in India as in research throughout the world, children in single-

Family Trouble

All the generalities just explained are averages, with many exceptions. However, two factors interfere with family function in every structure, ethnic group, and nation: low income and high conflict. Many families experience both, because financial stress increases conflict and vice versa.

Wealth and Poverty

Family income correlates with both function and structure. Marriage rates fall in times of recession, and divorce correlates with unemployment. The effects of poverty are cumulative; low socioeconomic status (SES) is especially damaging for children if it begins in infancy and continues through middle childhood (G. Duncan et al., 2010). Low SES correlates with many other problems, and “risk factors pile up in the lives of some children, particularly among the most disadvantaged” (Masten, 2014, p. 95).

Several scholars have developed the family-

If economic hardship is ongoing, if uncertainty about the future is high, if parents have little education—

Adults whose upbringing included less education and impaired emotional control often find it difficult to find employment and care for their children, and then low income adds to their difficulties (Schofield et al., 2011). Health problems in infancy may lead to “biologically embedded” stresses that impair adult well-

If all this is so, more income means better family functioning, especially if the income is stable, not a windfall. For example, children in single-

428

In fact, reaction to wealth may also cause difficulty. Children in high-

Conflict

There is no disagreement about conflict: Every researcher agrees that family conflict harms children, especially when adults fight about child rearing. Such fights are more common in stepfamilies, divorced families, and extended families, but nuclear families are not immune. In every family, children suffer not only if they are abused, physically or emotionally, but also if they merely witness their parents’ abuse. Fights between siblings can be harmful, too (Turner et al., 2012).

Researchers have hypothesized that children are emotionally troubled in families with feuding parents because of their genes, not because of witnessing the parents fighting. The idea is that the parents’ genes lead to marital problems and that children who inherit those same genes will have similar temperaments. If that is the case, then it doesn’t matter if children are exposed to their parents’ conflicts.

This idea was tested in a longitudinal study of 867 twin pairs (388 monozygotic pairs and 479 dizygotic pairs), all married with an adolescent child. Each adolescent was compared to his or her cousin, the child of one parent’s twin (Schermerhorn et al., 2011). Thus, this study had data on family conflict from 5,202 individuals—

The researchers found that, although genes had some influence, witnessing conflict had a more powerful effect, causing externalizing problems in boys and internalizing problems in girls. In this study, quiet disagreements did little harm, but open conflict (such as yelling when children could hear) or divorce did (Schermerhorn et al., 2011). That leads to an obvious conclusion: Parents should not fight in front of their children.

SUMMING UP Families serve five crucial functions for school-

Nuclear families (headed by two biological parents) are the most common family structure and tend to provide more income, stability, and parental attention, all of which benefit children. Many other families are headed by a single parent, usually the mother—

Children sometimes do well in every structure, but each structure has vulnerabilities. Although structures affect function, no structure inevitably harms children, and no structure (including nuclear) guarantees optimal function. Poverty and wealth can both cause stress, which interferes with family function: When parents worry about income, they are less likely to be patient and responsive with their children. Conflict between the parents affects the children, no matter what the family structure.

429

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 13.7

8XqW5V6LAuZ3R53UqFXVKMlazDt35OCDeGqBxg4viDFbJGuvpXGdtc0Wzni500GPRlLu2C7RZwt9NuxpNN/Wu8RrGZoG+BmTm85r4Ul5mCwOoGwRThe age of each child at the time of significant events, such as parental divorce, can cause different effects on each child. Each child has a different relationship with each parent, so that even though the children are raised in the same household with the same parents, the children's experiences may vary.Question 13.8

dspv5kO2Wk4fx5C2mtrH/WJW8AAbqBV5shAQHBw4miVDefBJMuVSqia0Zc1vF7YvAuldv6DPnF7l/Ok83q/OXTqBwN8yhGHzFamily structure refers to the legal and genetic connections among people living in the same household, e.g., single–parent families, step– families, or three– generational families. Family function refers to how a family cares for its members; some families function well, whereas others are dysfunctional. Question 13.9

UeZtQz1JZMVWzUeT/PqKZ/lL6oCOOhSwltz4OkMtq3NQfeTsHL6lG4YbGGK8kwvuCMfK/Jmh5YXOLh0MAAVAgHiHAeDC7N0rDXfNp4vxuDeX/P/5Middle childhood is a time when children really need continuity, not change; peace, not conflict. Routine is important to children's sense of security, so disruptions in home life are especially challenging for this age group.Question 13.10

7pFl7RACrZxI2twroKr6s7+S869XyRsdubYfPbISQ6uQP8ECIA1MNmTWwD3ElufCpAsDwk4q5biJRTSu5jOJp0PRh2tIqxpMThe family structures discussed in the text include: Nuclear: Two parents and their children.

Nuclear: Two parents and their children. Single-

Single-parent: One parent and his or her children.  Extended family: Nuclear or single-

Extended family: Nuclear or single-parent family plus other relatives, such as grandparents (three or more generations living in one home).  Polygamous: One husband with two or more wives

Polygamous: One husband with two or more wives Question 13.11

5IGZeQG4Fdx3T1Yn9W9D5zF1eEL79N4DSKQ0Ic16oPhwUmxEQZmxRhJGk9GY5eDWFeEG457cslNZrfsqP6l3kBPyowfQnvHFNuclear families tend to function best, at least in part because the people who marry tend to be better educated and to stay married. Having married parents benefits children by increasing the likelihood of parental involvement and decreasing the likelihood of neglect and abuse. Household income for nuclear families is also higher than for single–parent families. Question 13.12

Hw3dL9mYVLb3vz/Bsdzy6CNUHZBJmy0GI6HIvKTIqw8GgHiYc/3lkjKHN/LViBJlb8V6Fqrm1+sOdN8aEUrW/5XbgC96GAEtdavCXprDEJOLLVCCyATrjaWb9b+3g5Oe8dMzFEq3SfiSKshxKpi+PmnB5wTnVeUNYIAZBS0OsQxzcm6YZxRQTu7sW0E=Three reasons include: 1) lower income; 2) less stability; and 3) less parental availability to meet children's needs.Question 13.13

Lv31SSa41Kt2r7UfYupWoOf43oTg2O6ADRDUdp1g8YqWsO+rQtyL4ksrAYRzujSkkLtqhZPFHh6NOQcBvMseOry/7rclMqVx3yQnMAPNk3o=Two–parent families seem to function best worldwide, but in some European cultures, non– married parents provide families as stable as married couples in the United States. Single parenthood is common among African Americans, and the community routinely supports single parents. Asian American families function best with nuclear families, and Hispanic American families function well with nuclear or extended families. Question 13.14

o/DLX+AndoVG5Yo4HsH1mjADPuKiBCv4kZQKVBwQmuoetzEQLgCeYVwRGp2VcswRDM7IY7fdtTDaPVvnTqo56KKGjaCLJ/VyFgtFWLeXvnuwqJFnJoMVy26xZU72ZL9w5rG50doaXlIutUvME3W6/Iv4tmzFQFIZPa1ur1X7bqk1wJ/hQWvD81xIcIUtJARVThe family–stress model says that the crucial question for any risk factor is whether it increases stress. If poverty increases stress, and the adults' reactions are negative (tense, hostile), then family function may suffer.