Sadness and Anger

Adolescence is usually a wonderful time, perhaps better for current generations than for any earlier cohort. Nonetheless, troubles plague about 20 percent of youths. For instance, one specific survey of over ten thousand 13-

It is typical for an adolescent to be momentarily less happy and more angry than younger children, but teen emotions often change quickly (Neumann et al., 2011). For a few, however, negative emotions cloud every moment, becoming intense, chronic, even deadly.

Depression

The general emotional trend from childhood to early adolescence is toward less confidence and higher rates of depression, and then, gradually, self-

527

Universal trends, as well as family effects, are apparent. A report from China also finds a dip in self-

On average, self-

These generalities regarding depression apply to most disorders (Kessler et al., 2012). All studies find notable variability among people the same age, yet continuity within each person. Severe depression may lift but rarely disappears (Huang, 2010).

Context matters. One cultural norm is familism—the belief that family members should sacrifice personal freedom and success to care for one another. For immigrant Latino youth, self-

Clinical Depression

Some adolescents sink into clinical depression, a deep sadness and hopelessness that disrupts all normal activities. The causes, including genes and early care, predate adolescence. Then the onset of puberty—

Hormones are probably part of the reason for these gender differences, but girls also experience social pressures from their families, peers, and cultures that boys do not (Naninck et al., 2011). Perhaps the combination of biological and psychosocial stresses causes some to slide into depression.

Differential susceptibility is apparent. One study found that the short allele of the serotonin transporter promoter gene (5-

A cognitive explanation for gender differences in depression focuses on rumination—talking about, brooding over, and mentally replaying past experiences. Girls ruminate much more than boys, and rumination often leads to depression (Michl et al., 2013). For that reason, close mother–

528

Suicide

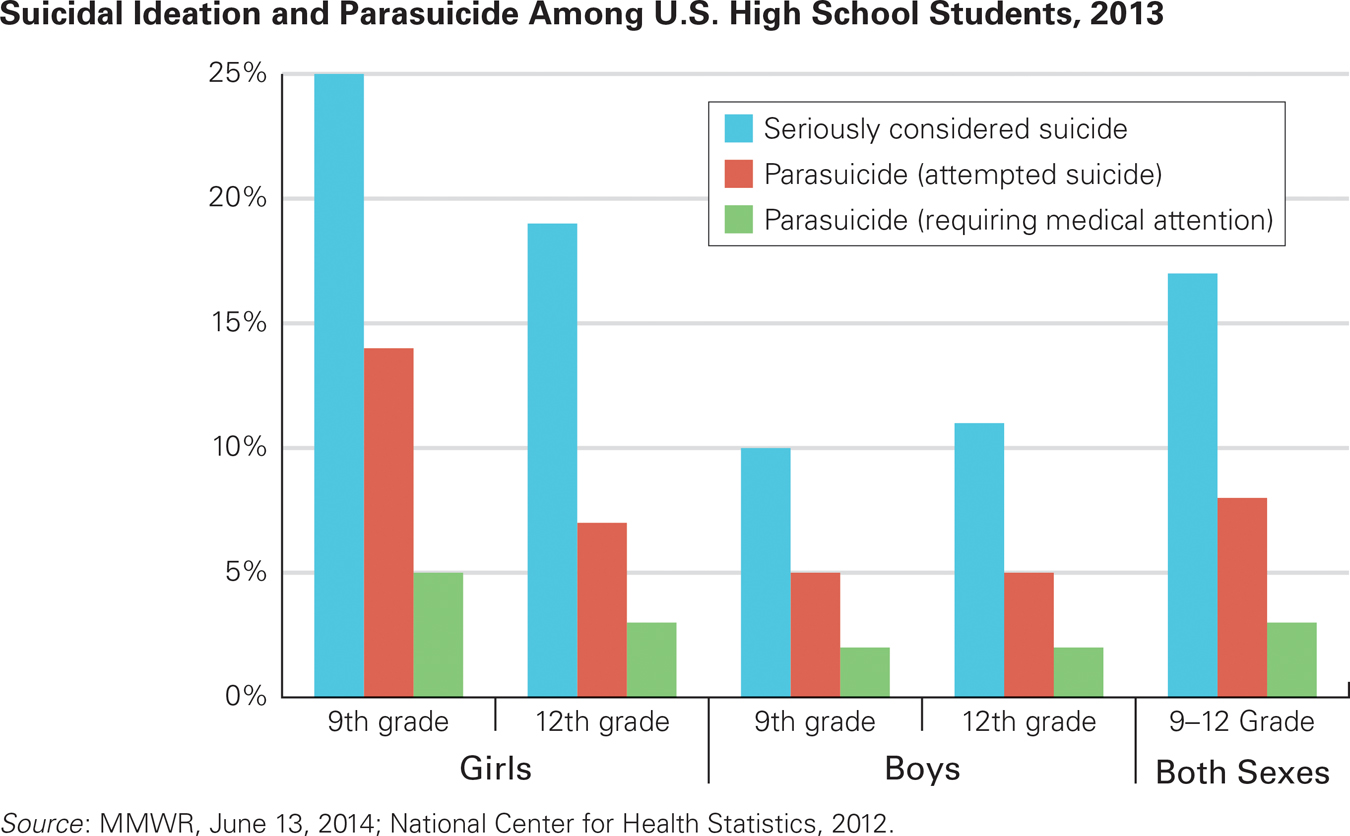

Serious, distressing thoughts about killing oneself (called suicidal ideation) are most common at about age 15. The 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey revealed that more than one-

Suicidal ideation can lead to parasuicide, also called attempted suicide or failed suicide. Parasuicide includes any deliberate self-

As you see in Figure 16.5, parasuicide can be divided according to instances that require medical attention (surgery, pumped stomachs, etc.) and those who do not, but any parasuicide is a warning. If there is a next time, the person may die. Thus parasuicide must be taken very seriously.

One form of psychotherapy that seems to reduce the risk of completed suicide is dialectical behavior therapy, designed to help the adolescent accept their moods, but not act on them (Miller et al., 2007). This seems a promising, although replicated experimental research regarding this therapy is needed (Berk et al., 2014).

Internationally, rates of teenage parasuicide range between 6 and 20 percent. Among U.S. high school students in 2013, 10.6 percent of the girls and 5.4 percent of the boys tried to kill themselves in the previous year (MMWR, June 13, 2014; see Figure 16.5).

Sad Thoughts Completed suicide is rare in adolescence, but serious thoughts about killing oneself are frequent. Depression and parasuicide are more common in girls than in boys, but rates are high even in boys. There are three reasons to suspect the rates for boys are underestimates: Boys tend to be less willing to divulge their emotions, boys consider it unmanly to try but fail to kill themselves, and completed suicide is higher in males than in females.

Especially for Journalists You just heard that a teenage cheerleader jumped off a tall building and died. How should you report the story?

Since teenagers seek admiration from their peers, be careful not to glorify the victim’s life or death. Facts are needed, as is, perhaps, inclusion of warning signs that were missed or cautions about alcohol abuse. Avoid prominent headlines or anything that might encourage another teenager to do the same thing.

529

Although suicidal ideation during adolescence is common, completed suicides are rare. The U.S. annual rate of completed suicide for people aged 15 to 19 (in school or not) is less than 8 per 100,000, or 0.008 percent, which is only half the rate for adults aged 20 and older (Parks et al., 2014). This is an important statistic to keep in mind whenever someone claims that adolescent suicide is “epidemic.” It is not. Of course, even one teenage suicide is one too many.

Because they are not logical and analytical, adolescents are particularly affected when they hear about someone’s suicide, either through the media or from peers (Niedzwiedz et al., 2014). That makes them susceptible to cluster suicides, which are several suicides within a group over a brief span of time. For that reason, media portrayal of a tragic suicide may inadvertently trigger more deaths.

In every large nation except China, girls are more likely to attempt suicide, but boys are more likely to complete it. In the United States, adolescent boys kill themselves four times more often than girls (Parks et al., 2014). The reason may be method: Males typically jump from high places or shoot themselves (immediately lethal), whereas females often swallow pills or cut their wrists, which allows time for conversation, intervention, and second thoughts. Given adolescent volatility, second thoughts are protective.

European American youth are three times more likely to commit suicide than African, Hispanic, or Asian Americans. Suicide is one of very few causes of death that increase with SES.

Delinquency and Defiance

Like low self-

Externalizing actions are obvious. Many adolescents slam doors, curse parents, and tell friends exactly how badly other teenagers (or siblings or teachers) have behaved. Some teenagers—

One issue is whether teenage anger is not only common but also necessary for normal development. That is what Anna Freud (Sigmund’s daughter, herself a prominent psychoanalyst) thought. She wrote that adolescent resistance to parental authority was “welcome … beneficial … inevitable.” She explained:

530

We all know individual children who as late as the ages of fourteen, fifteen or sixteen, show no such outer evidence of inner unrest. They remain, as they have been during the latency period, “good” children, wrapped up in their family relationships, considerate sons of their mothers, submissive to their fathers, in accord with the atmosphere, ideas and ideals of their childhood background. Convenient as this may be, it signifies a delay of their normal development and is, as such, a sign to be taken seriously.

[A. Freud, 2000, p. 263]

However, most contemporary psychologists, teachers, and parents are quite happy with well-

Some psychologists suggest that adolescent rebellion is a social construction. It might be an idea created and endorsed by many Western adults but not expected or usual in Asian nations (Russell et al., 2010).

Breaking the Law

Both the prevalence (how widespread) and the incidence (how frequent) of criminal actions are higher during adolescence than earlier or later. Arrest statistics in every nation reflect this fact, with 30 percent of African American males and 22 percent of European American males being arrested at least once before age 18 (Brame et al., 2014).

It would be good to know how many young people have broken the law but not been caught, or caught but not arrested. Confidential self-

However, the actual percentage is unknown, as some adolescents refuse to answer and some might brag (falsely) about skipping school, drinking underage, shoplifting, hurting another person, vandalism, and so on. Others might deny (again falsely) ever having done such a thing. Researchers in the Netherlands found that one-

Research on confessions to a crime is interesting in this regard. In the United States, about 20 percent of confessions are false: That is, people confess to a crime they did not commit. False confessions are more likely in adolescence, partly because of brain immaturity and partly because young people want to help their family members and please adults—

Many researchers in delinquency suggest that we need to distinguish two kinds of teenage lawbreakers (Monahan et al., 2013), as first proposed by Terri Moffitt (2001, 2003). Most juvenile delinquents are adolescence-

The other delinquents are life-

531

During adolescence, the criminal records of both types may be similar. However, if adolescence-

Causes of Delinquency

One way to reduce adolescent crime is to consider earlier behavior patterns and then stop delinquency before the police become involved. Parents and schools need to develop strong and protective relationships with children, teaching them emotional regulation and prosocial behavior, as explained in earlier chapters. In early adolescence, three pathways to dire consequences can be seen:

Stubbornness can lead to defiance, which can lead to running away. Runaways are often victims as well as criminals (e.g., falling in with prostitutes and petty thieves).

Shoplifting can lead to arson and burglary. Things become more important than people.

Bullying can lead to assault, rape, and murder.

Each of these pathways demands a different response. The rebelliousness of the first can be channeled or limited until less impulsive anger prevails with maturation. Those on the second pathway require stronger human relationships and moral education. Those on the third present the most serious problem; their bullying should have been stopped in childhood, as Chapter 10 and Chapter 13 explained. In all cases, early warning signs are present, and intervention is more effective earlier than later (Loeber & Burke, 2011).

Adolescent crime in the United States and many other nations has decreased in the past 20 years. Only half as many juveniles under age 18 are currently arrested for murder than were in 1990. For almost every crime, boys are arrested at least twice as often as girls are.

No explanation for declining rates or gender differences is accepted by all scholars. Regarding gender, it is true that boys are more overtly aggressive and rebellious at every age, but this may be nurture, not nature (Loeber et al., 2013). Some studies find that female aggression is typically limited to family and friends and therefore less likely to lead to an arrest.

Regarding the drop in adolescent crime, many possibilities have been suggested: fewer high school dropouts (more education means less crime); wiser judges (who now have community service as an option); better policing (arrests for misdemeanors are up, which may warn parents); smaller families (parents are more attentive to each of two children than each of twelve); better contraception and legal abortion (wanted children are less likely to become criminals); stricter drug laws (binge drinking and crack use increase crime); more immigrants (who are more law-

Nonetheless, adolescents remain more likely to break the law than adults. To be specific, the arrest rate for 15-

532

SUMMING UP Compared with people of other ages, many adolescents experience sudden and extreme emotions that lead to powerful sadness and explosive anger. Supportive families, friends, neighborhoods, and cultures usually contain and channel such feelings. For some teenagers, however, emotions are unchecked or intensified by their social contexts. This situation can lead to parasuicide (especially for girls), to minor lawbreaking (for both sexes), and less often, to completed suicide or jail (especially for boys). Incidence statistics sometimes counter public impressions: Teenage suicide is much less common than adult suicide (even though many teenagers contemplate suicide), and almost all teenagers break the law (although arrest and imprisonment rates are much higher for boys). Developmentalists distinguish between adolescent-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 16.21

wRfqTkqw3GmcIVO6XncXGewayTKY5FWgejSGeglDMoVB5+d17k+DGPA2ZCFr/OfAATcbAmKwxU3vTTuBxIsgrLYogGXT/Np9n+MV4b9rLgE=It is typical for an adolescent to be momentarily less happy and more angry than younger children. Clinical depression moves beyond sadness that is typical of adolescence and encompasses feelings of deep sadness and hopelessness that disrupts all normal regular activities.Question 16.22

WcwbxB5VLviUCHAk/CN/d0JTPlcf+UYS9D/+UN6r+MMcXk1H5ajPd1eifo7v10zaUE7jozzp7eMcOzVWH3stzdaDwSVB5prbKlHEKA==1) The rate, low as it is, is much higher than it appeared to be 50 years ago. 2) Statistics on “youth” often include emerging adults aged 18 to 25, whose suicide rates are higher than those of adolescents. 3) Adolescent suicides capture media attention, and people of all ages make the logical error called base rate neglect. 4) Parasuicides may be more common in adolescence than later.Question 16.23

ov6WRPsp5sUMpRNlLsAbsKQk8mKEiRrOWNIcKAUCsP+0tRYfwCGWCCxOMCJNYpOkmtZyl5XxspcuaJgyoDbI/ZESQ0220EmSA cognitive explanation for gender differences in depression focuses on rumination—talking about, remembering, and mentally replaying past experiences. Girls ruminate much more than boys, and rumination often leads to depression. Question 16.24

YJmTPmkyzGMQ0X8QVmkpdZg90GMkwwgmBc3Pvu6K3fG6XNoQnN2iC01nXrhLi8jxcEDWUNtlAt7hj+WuHJHPfVTBiB5awQiN0y/bPQ==Because they are not logical and analytical, adolescents are particularly affected when they hear about a suicide, either through the media or from peers. This makes them susceptible to cluster suicides, a term for the occurrence of several suicides within a group over a brief span of time.Question 16.25

AsUypu79yr8zGNP5VMgns9Ix6N+gemzPjvKO97sQnjCnLiVTlsSbUlZSVX1Gj/Aii1Ovgk++mWUxwIhF5bJxkq+dTqv4x0NR+vywMRnB782iZ6v0loyeAvQD0UQgBpfzRUtkVxC64dekQYA6HyYOcE5QzIq7d1MrkCCOYfgjVGEHCcoEt8d/70IvB07qt60ce73GbLnhtQryM9lNVHI7Fmf9rwZI9yJX7qL8oPohPsUzKijS6+HFNGwKrnBrkpOCQUYUfAO9csdFbNk0bgFWRpCAO7Ic6hCm9/MeeIL2Dde17l/fuTn/Xuu6cSE=Both involve antisocial behaviors and may result in criminal records. Most juvenile delinquents are adolescence–limited offenders, adolescents whose criminal activity stops by age 21. They break the law with their friends, facilitated by their chosen antisocial peers. More boys than girls are in this group. The other kind of delinquents are life– course– persistent offenders, people who break the law before and after adolescence as well as during it. Their law breaking is more often alone than as part of a gang, and the cause of their problems is neurological impairment. Question 16.26

+cyQ1r7YU6+4Xr1+EHmbjpwzbq+bXZGTEGYxUmOv/p9VgH8mUFZ0jGuuBq5vTcFkADoOEA==A number of factors can contribute to delinquency. Stubbornness can lead to defiance, which can lead to running away. Runaways are often victims as well as criminals. Shoplifting can lead to arson and burglary and bullying can lead to assault, rape, and murder. Being male is linked to an increase in aggression and rebelliousness. Factors that have been linked to a decrease in delinquency include: more education, wiser judges, better policing, smaller families, better contraception, stricter drug laws, and less lead in the blood.