As Time Goes On

The effects of time are the heartbeat of human development, the essence of what we study. As already explained, an earlier idea—

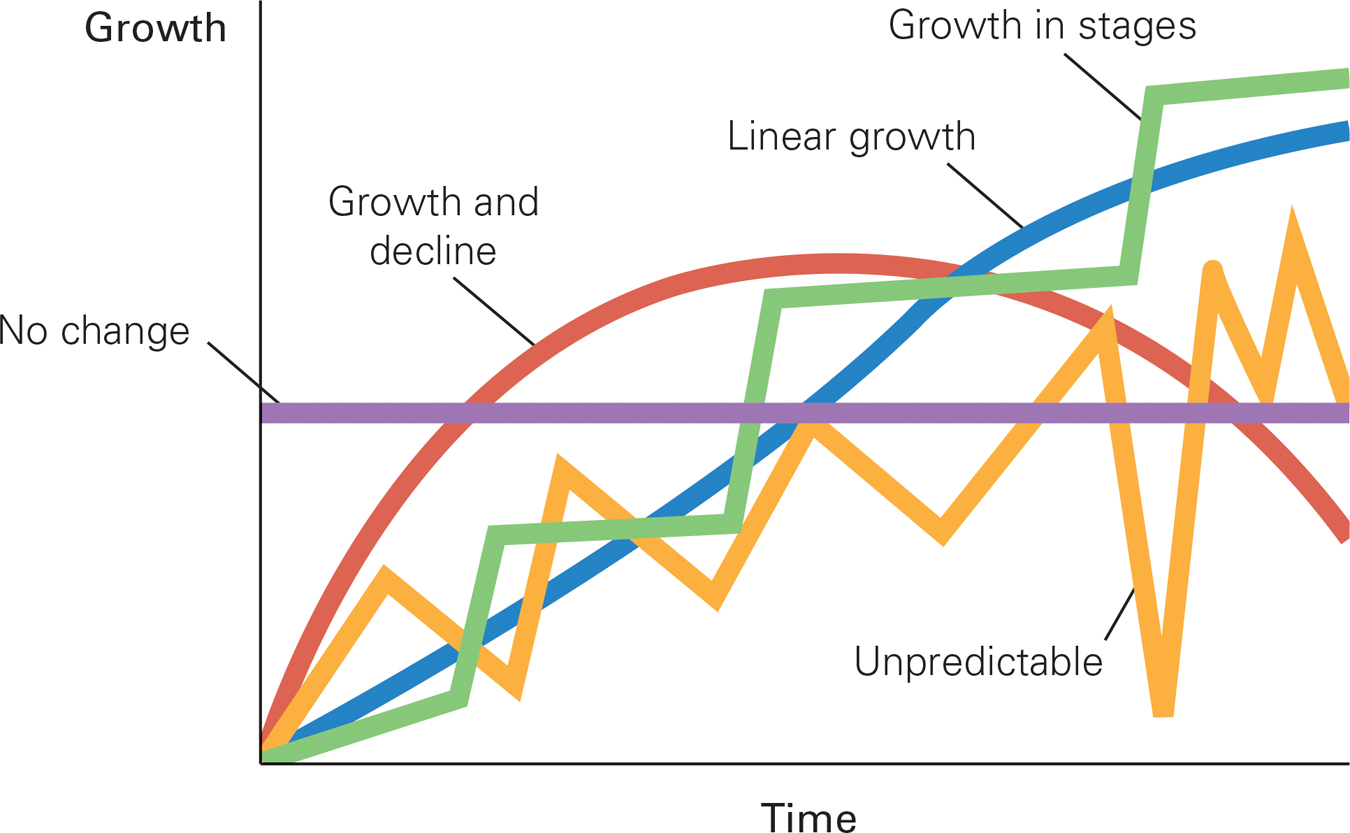

Patterns of Developmental Growth Many patterns of developmental growth have been discovered by careful research. Although linear progress seems most common, scientists now find that almost no aspect of human change follows the linear pattern exactly.

The pace of change differs as well. Sometimes discontinuity is evident: Change can occur rapidly and dramatically, as when caterpillars become butterflies. Sometimes continuity is found: Growth can be gradual, as when redwoods add rings over hundreds of years. And sometimes no change seems to occur: Stability itself is remarkable.

Humans experience simple growth, radical transformation, improvement, and decline as well as stability, change, and continuity—

No matter what the pattern, age is always significant, and that is the focus of our study. Is it normal for a boy to throw himself down, kicking and screaming, when he is frustrated? Yes, if he is 2 years old; no, if he is 12. Is it normal for a girl to be interested in boys? Yes, at age 16; no, at age 6. More broadly, children think, play, and learn differently depending partly on their age.

Critical Periods

Some changes are sudden and profound because of a critical period, a time when something must occur for normal development or the only time when an abnormality can occur. For instance, the critical period for humans to grow arms and legs, hands and feet, fingers and toes, is between 28 and 54 days after conception. After that, it is too late: Unlike some insects, humans never grow replacement limbs or digits.

17

Thalidomide

We know the critical period for limb formation because of a tragic occurrence. Between 1957 and 1961, thousands of newly pregnant women in 30 nations took thalidomide, an anti-

If an expectant woman ingested thalidomide during the 26 days of the critical period for limb formation, her newborn’s arms or legs were malformed or absent (Moore & Persaud, 2007). Whether all four limbs, or just arms, or only hands were missing depended on exactly when the drug was taken. If thalidomide was ingested only after day 54, the newborn had normal body structures.

Sensitive Periods

Life has few critical periods. Often, however, a particular development occurs more easily—

An example is found in language acquisition. If children do not communicate in their first language between ages 1 and 3, they might do so later (hence, these years are not critical), but their grammar is impaired (hence, these years are sensitive).

Similarly, childhood is a sensitive period for learning to pronounce a second or third language with a native accent. Many adults master a new language, but strangers might ask, “Where are you from?” Native speakers can detect an accent that reveals that the second language was learned after childhood.

Often in development, individual exceptions to general patterns occur. Sweeping generalizations, like those in the language example, do not hold true in every case. Accent-

Because of sensitive periods, however, such exceptions are rare. According to a study of native Dutch speakers who become fluent in English, only 1 in 20 such adults masters native pronunciation (Schmid et al., 2014).

Ecological Systems

A leading developmentalist, Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–

Systems Within Systems Within Systems

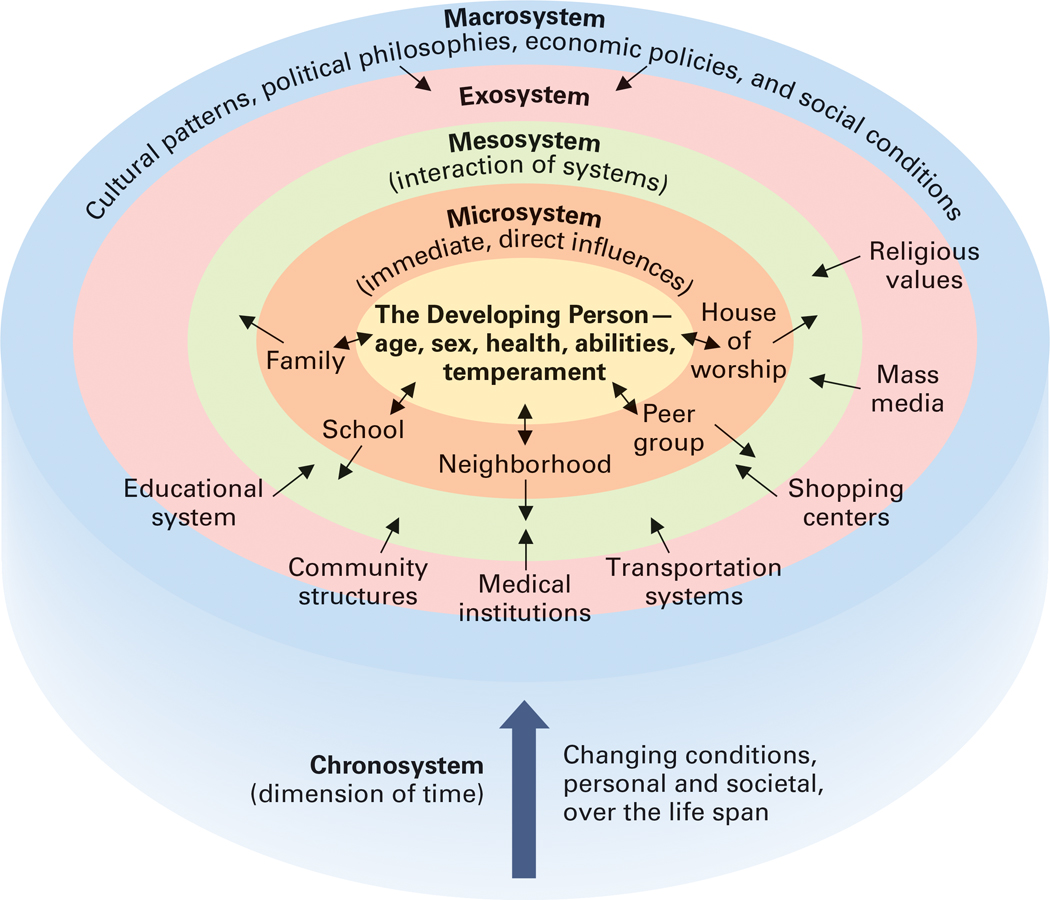

The ecological-

The Ecological Model According to developmental researcher Urie Bronfenbrenner, each person is significantly affected by interactions among a number of overlapping systems, which provide the context of development. Microsystems—family, peer groups, classroom, neighborhood, house of worship—

18

Also important are exosystems (local institutions such as school and church) and macrosystems (the larger social setting, including cultural values, economic policies, and political processes).

Two more systems are related to these three. One is the mesosystem, consisting of the connections among the other systems. The other is the chronosystem (literally, “time system”); it is the historical context that allows developmentalists to focus specifically on the influence of changing historical circumstances.

19

Bronfenbrenner believed that people need to be studied in their natural contexts repeatedly over time (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; 1986). He looked at children playing, or mothers putting babies to sleep, or nurses in hospitals—

Toward the end of his life, Bronfrenbrenner renamed his approach bioecological theory to highlight the role of biology, recognizing that systems within the body (e.g., the sexual-

Historical Change

In studying development, it matters, of course, how old a child is, but it also matters what the political and medical conditions are when a child reaches a particular age. Both generational and cohort effects need to be considered. This needs some explanation.

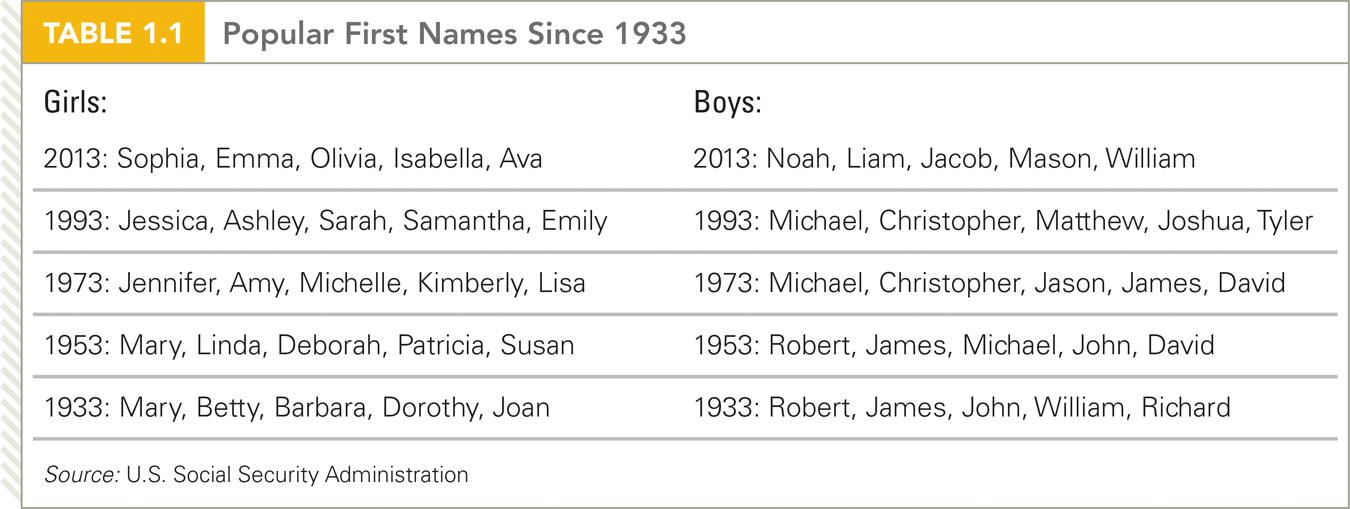

All persons born within a few years of one another are called a cohort. Cohorts travel through life together, affected by the interaction between their chronological age and the values, events, technologies, and culture of the era. From the moment of birth, when parents decide the name of their baby, historical context is crucial (see Table 1.1).

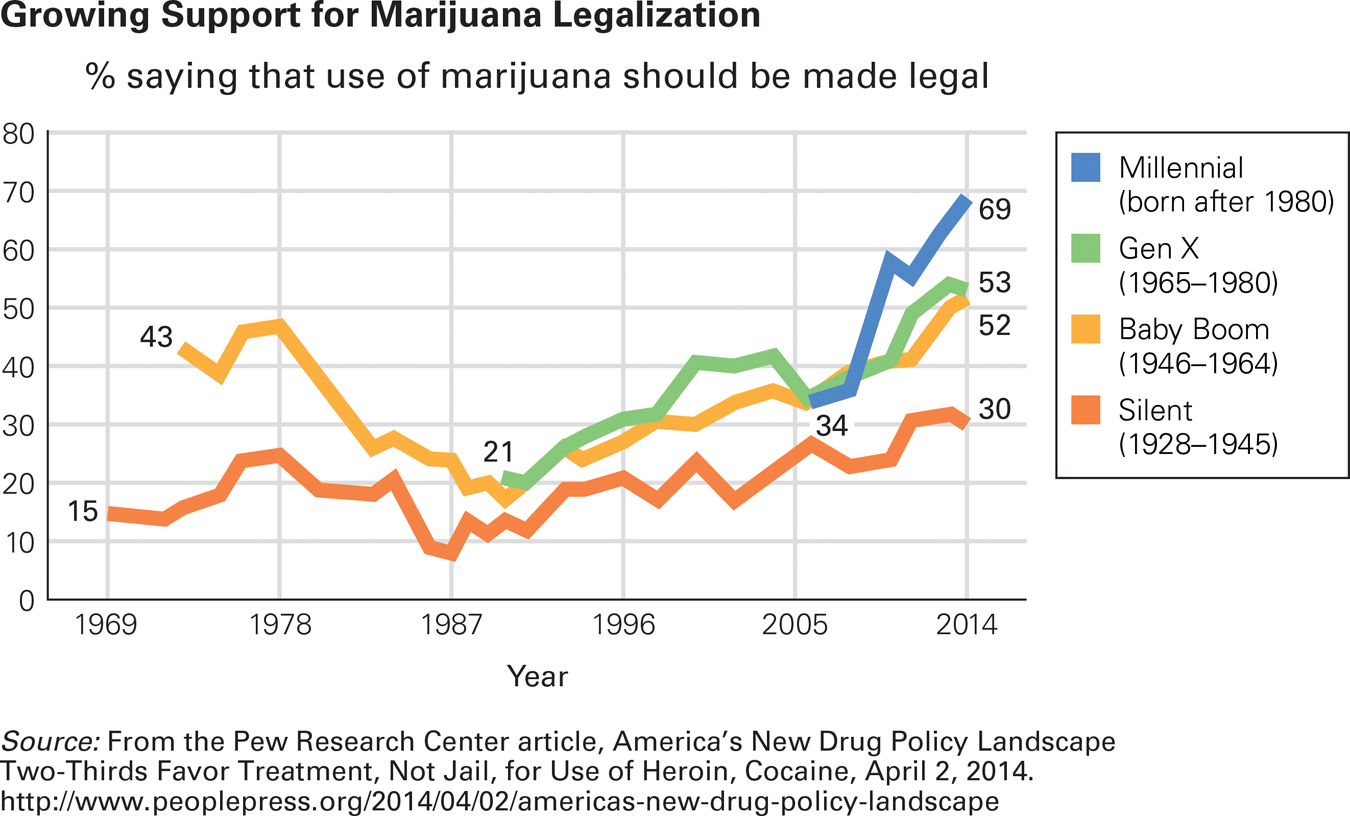

Consider attitudes and data about marijuana. In the United States in the 1930s, marijuana was declared illegal, but enforcement was erratic. Then in the 1980s, marijuana was labeled a “gateway drug,” likely to lead to drug abuse and addiction (Kandel, 2002). People were arrested and jailed for possession of even a few ounces of the drug.

From 1990 on, attitudes gradually changed. By 2014, general marijuana use became legal in two states, and medical use was permitted in several others. According to a Gallup poll, more than half (54 percent) of Americans approve making marijuana use legal, as long as it is used by adults and not in public (Motel, 2014).

These historical shifts have had a notable effect on high school students (Johnston et al., 2014 and previous years). In 1978, only 12 percent thought experimental use of marijuana was harmful, and more than half had tried the drug. In 1991, when the gateway drug message became widespread, 80 percent thought there was “great risk” in regular use and only 21 percent ever smoked the drug. Since then, marijuana use has increased as attitudes have become more accepting: Approximately one-

Question 1.12

OBSERVATION QUIZ Why is the line for Millennials much shorter than the line for the Silent Generation?

Because surveys rarely ask children their opinions, and the Millennials did not reach adulthood until about 2005.

Thus cohort, more than generation, influences attitudes and behavior toward marijuana. The same is true for adults’ attitudes and behavior: It matters more when an adult was born than how old that adult is. It is wiser, for example, to seek generalities about people born in 1950 rather than about people who are in their 60s, or 70s, or whatever (see Figure 1.6).

Not Generation Sometimes people praise (or criticize) young adults for their attitudes or behavior, but perhaps people should credit (or blame) history instead. Note that even when they were young, the oldest generations did not think that marijuana should be legal, nor were they likely to endorse same-

20

Plasticity

The term plasticity denotes two complementary aspects of development: Human traits can be molded (as plastic can be), and yet people maintain a certain durability (as plastic does). This provides both hope and realism—

Plasticity is basic to our contemporary understanding of human development because it simultaneously incorporates two facts: People can change over time, and new behavior depends partly on what has already happened.

This is evident in one of the newer approaches to development, the dynamic-

Especially for Future Teachers Does the classroom furniture shown in the photograph to the right affect instruction?

Yes. Every aspect of the ecological context affects what happens. In this classroom, tables and movable chairs foster group collaboration and conversation-potent learning methods that are difficult to achieve when desks and seats are bolted to the floor and the teacher sits behind a large desk.

[S]easons change in ordered measure, clouds assemble and disperse, trees grow to a certain shape and size, snowflakes form and melt, minute plants and animals pass through elaborate life cycles that are invisible to us, and social groups come together and disband.

[Thelen & Smith, 2006, p. 271]

Question 1.13

OBSERVATION QUIZ What country is this?

The three Somali girls wearing headscarves may have thrown you off, but these first–

21

Note the word dynamic: Physical contexts, emotional influences, the passage of time, each person, and every aspect of the ecosystem are always interacting, always in flux, always in motion. For instance, a new approach to developing the motor skills of children with autism spectrum disorder stresses the dynamic systems that undergird movement—

Plasticity is especially useful in understanding the potential of a particular person: Everyone is constrained by past circumstances but not confined by them. David is an example.

a case to study

Plasticity and David

My sister-

He was born in 1967, just when parents and educators successfully advocated that “every child can learn.” Plasticity meant there was hope for David, and my brother and his wife sought out specialists who believed David could defy early predictions.

For example, most 9-

At age 1 David did not talk, but an audiologist found that he could hear, and teachers encouraged my brother and his wife to sing and read to him. At age 2½ he did not chew, but a nutritionist showed his parents how to force him to eat food that was not pureed. In middle childhood, doctors repaired his heart, removed the remaining cataract, realigned his jaw, replaced the dead eye with a glass one, and straightened his spine with a brace.

Dozens of educators taught him. David attended three specialized preschools, then a mainstreamed public school, then a special high school, then the University of Louisville.

Remember, plasticity cannot erase genes, childhood experiences, or permanent damage. David’s disabilities are always with him. But the interaction of nature and nurture meant that, by age 10, David had skipped a year of school and was a fifth-

David now works as a translator of German texts. He enjoys that because, as he told me, “I like providing a service to scholars, giving them access to something they would otherwise not have.” He uses a computer to read and write.

Family members continue to be crucial to his well-

22

SUMMING UP A critical period is a time when something must occur to ensure normal development or the only time when an abnormality might occur. Critical periods are common in fetal development, but rare later on. A sensitive period is a time when a specific development can occur most easily, with genes as well as experiences affecting what occurs in each sensitive time.

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological approach notes that each person is situated within larger systems of family, school, community, and culture, all of which are constantly changing as time goes on. Each person is affected by the particular context of their society at the time: Attitudes and habits are influenced more by cohort than by age.

Although many constraints affect development, people alter and transcend their contexts and conditions, demonstrating plasticity, as evident in the dynamic-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 1.14

xpYflNqgR4hBfePWAHLvpFCEIz/o3rhqkgP18KoIcMXrErEa+NFhvoGtDMqYlzT9gQn9tJ02XpxFcQirtJ42tpjObimMjXIvPv1nxA==A critical period is a time when a particular type of developmental growth (in body or behavior) must happen for normal development to occur. A sensitive period is a time when a certain type of development is most likely, although it may still happen later with more difficulty.Question 1.15

rUGw33UP+o3XmzmKGAPtE+IsCQpB6yUdLHFjxxvGp+N9gWTvN9dFLAX8r3C1Pgsy6YtoopRwZnrefDu953vD6Q==We know the critical period for limb formation because of thalidomide. If an expectant woman ingests thalidomide during the 26 days of the critical period for limb formation, her newborn's limbs will be malformed or absent.Question 1.16

kiLv6eEBiAK4v85Om5lJweJx6gYyaDKf5Ym/NVLsKnVKTwBglU7+S3tAE59MYfglkNuZ4U36Fzk1JI+Ard+HBMAhg/uZYSCU7Lgq8ptoLXbO1zA0QcBSYpMe9fqnuu/+ax7QiBv5t+Z8q58JUPnAh9HRyhW40SSCBronfenbrenner emphasizes all of the contextual influences on the developing child as time goes by.Question 1.17

oGhLXnslVVg833EZMqO+hX3C4Qyo6VqJELSs0HriVX9jt4Me2Rsf4SxktlCvFXFz1O5yHyu2Qquu6AQo2gYFc569sG0=Cohorts travel through life together, affected by the interaction between their chronological age and the values, events, technologies, and culture of the era. Cohort, more than generation, influences the attitudes and behavior of people born within the same historical period.Question 1.18

fNkD9dksQj5avYDROPfMA8LlASvvmmMTC77iJX39+g3Yoy3qgFSx15kqF0LE2+C2oHs7oANspeTXL1qXDVIOzSvbcik=Plasticity denotes two complementary aspects of development: Human traits can be molded (as plastic can be), and yet people maintain a certain durability (as plastic does). This provides both hope and realism—hope because change is possible and the realism because development builds on what has come before.