Behaviorism: Conditioning and Social Learning

Another comprehensive theory arose in direct opposition to the psychoanalytic notion of the unconscious. John B. Watson (1878–

43

Why don’t we make what we can observe the real field of psychology? Let us limit ourselves to things that can be observed, and formulate laws concerned only with those things…. We can observe behavior—

[Watson, 1998, p. 6]

According to Watson, if psychologists focus on behavior, they will realize that everything can be learned. He wrote:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-

[Watson, 1998, p. 82]

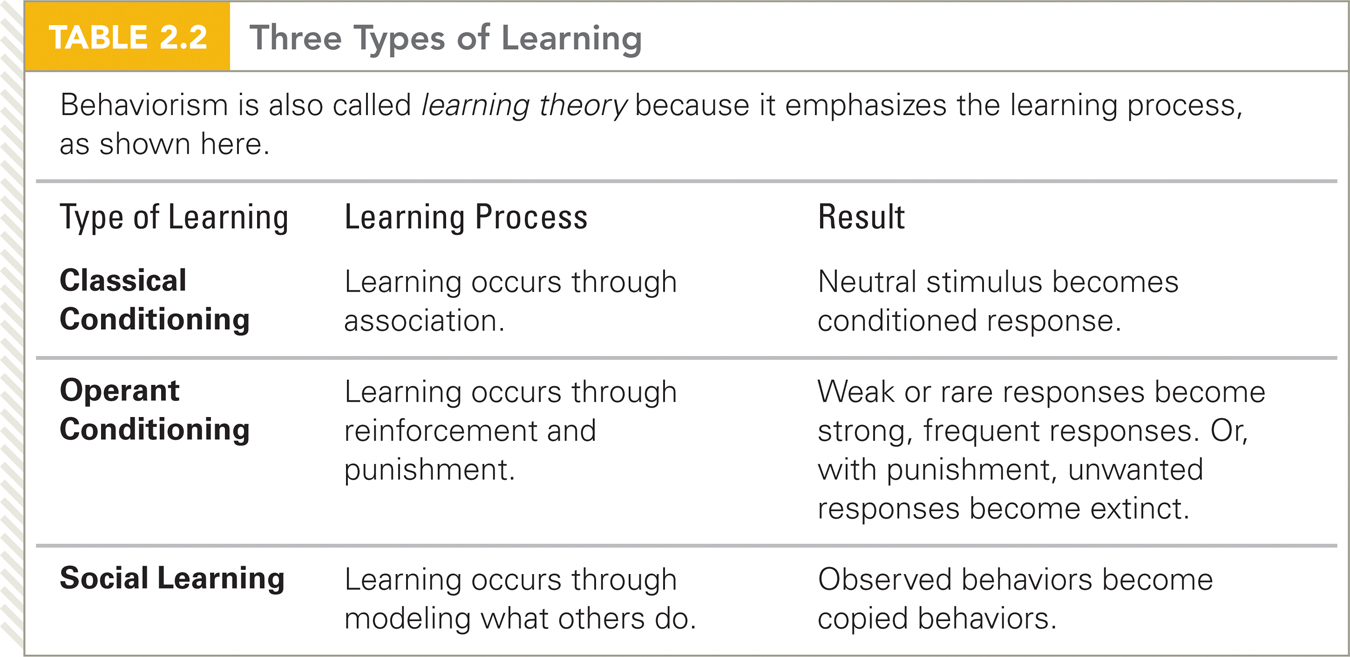

Other psychologists, especially in the United States, agreed. They developed behaviorism to study observable behavior, objectively and scientifically. Behaviorism is also called learning theory because it describes the learning process.

For everyone at every age, behaviorists believe there are natural laws of human behavior. Those laws allow simple actions to become complex competencies, as various forces in the environment affect each action. Learning is far more than an academic skill, such as learning to read. It includes learning to suck on a nipple, learning to smile at a caregiver, learning to hold hands when crossing the street, and so on.

Learning theorists believe that development occurs not in stages but bit by bit. A person learns to talk, read, or anything else one tiny step at a time. Behaviorists study conditioning, the processes by which responses link to particular stimuli. In the first half of the twentieth century, behaviorists described only two types of conditioning: classical and operant. Both are still described in parenting-

Classical Conditioning

A century ago, Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov (1849–

Pavlov began by sounding a tone just before presenting food. After a number of repetitions of the tone-

In classical conditioning, a person or animal learns to associate a neutral stimulus with a meaningful stimulus, gradually responding to the neutral stimulus in the same way as to the meaningful one. In Pavlov’s original experiment, the dog associated the tone (the neutral stimulus) with food (the meaningful stimulus) and eventually responded to the tone as if it were the food itself. The conditioned response to the tone, no longer neutral but now a conditioned stimulus, was evidence that learning had occurred.

OBSERVATION QUIZ In appearance, how is Pavlov similar to Freud, and how do both look different from the other theorists pictured?

Both are balding, with white beards. Note also that none of the other theorists in this chapter have beards—

Behaviorists see dozens of examples of classical conditioning in child development. Infants learn to smile at their parents because they associate them with food and play; toddlers become afraid of busy streets if the noise of traffic repeatedly frightens them; students enjoy—

44

One specific example of classical conditioning is called the white coat syndrome, which occurs in people for whom past experiences with medical professionals (who wore white coats) conditioned anxiety. For that reason, when someone dressed in white takes their blood pressure, it is higher than it would be under normal circumstances.

White coat syndrome is apparent in about half of the U.S. population over age 80 (Bulpitt et al., 2013). It began when those elders were children. Today many nurses, especially in pediatrics, wear colorful blouses and many doctors wear street clothes: They dress to prevent conditioned anxiety.

Operant Conditioning

The most influential North American proponent of behaviorism was B. F. Skinner (1904–

In other words, he went beyond observation of learning by association, in which one stimulus is paired with another stimulus (in Pavlov’s experiment, the tone with the food). He focused instead on what happens after a behavior elicits a particular response. If the consequence that follows is enjoyable, the animal tends to repeat the behavior; if the consequence is unpleasant, the animal might not. Usually, operant conditioning occurs only after several repetitions of an action that result in similar consequences.

Pleasant consequences are sometimes called rewards, but behaviorists do not call them that because what some people consider a reward may actually be a punishment, an unpleasant consequence. For instance, some teachers think they are rewarding children by giving them more recess time, but some children may hate the social pressures of recess.

The opposite is true as well: Something thought to be a punishment may actually be a positive consequence. For example, parents think they punish their children by withholding dessert. But a particular child might dislike the dessert, so being deprived of it is no punishment.

Sometimes teachers send misbehaving children out of the classroom and principals suspend them from school. However, if a child hates the teacher, leaving class is rewarding, and if a child hates school, suspension is a reward. Indeed, research on school discipline finds that some measures, including school suspension, increase later misbehavior (Osher et al., 2010).

45

Especially for Teachers Same problem as previously (talkative kindergartners), but what would a behaviorist recommend?

Behaviorists believe that anyone can learn anything. If your goal is quiet, attentive children, begin by reinforcing a moment's quiet or a quiet child, and soon all the children will be trying to remain quietly attentive for several minutes at a time.

In order to stop misbehavior, it is more effective to encourage good behavior, to “catch them being good.” Three times as many African American children are suspended as European American children, even though white children are the majority in schools. The statistics on school discipline raise a troubling question: Is suspension a punishment for the child, or is it a reward for the teacher? Or even a sanctioned expression of racism (Tajalli & Garba, 2014; Shah, 2011)?

The true test is the effect a consequence has on the individual’s future actions, not whether it is intended to be a reward or a punishment. A child, or an adult, who repeats an offense may have been reinforced, not punished, for the first infraction.

Consequences that increase the frequency or strength of a particular action are called reinforcers, in a process called reinforcement (Skinner, 1953). According to behaviorism, almost all of our daily behavior, from saying “Good morning” to earning a paycheck, can be explained as the result of past reinforcement.

Social Learning

At first, behaviorists thought all behavior arose from a chain of learned responses, the result of either the association between one stimulus and another (classical conditioning) or of past reinforcement (operant conditioning). Thousands of experiments inspired by learning theory have demonstrated that both classical conditioning and operant conditioning occur often as children grow.

However, research finds that people at every age are social and active, not just reactive. Instead of responding merely to their own direct experiences, “people act on the environment. They create it, preserve it, transform it, and even destroy it … in a socially embedded interplay” (Bandura, 2006, p. 167).

That social interplay is the foundation of social learning theory (see Table 2.2), which holds that humans sometimes learn without personal reinforcement. This learning often occurs through modeling, when people copy what they see others do (also called observational learning). However, modeling is not simple imitation, and some people are more likely to be followed as roles models than others. Indeed, people model only some actions, of some individuals, in some contexts, and sometimes they do the opposite of what they have observed.

Generally, modeling is most likely to occur when the observer is uncertain or inexperienced (which explains why modeling is especially powerful in childhood) and when the model is admired, powerful, nurturing, or similar to the observer (Bandura, 1986, 1997).

46

Social learning is particularly noticeable in early adolescence, when children want to be similar to their peers despite their parents’ wishes. That impulse may continue into adulthood. Is your speech, hairstyle, or choice of shoes similar to those of your peers, or of an entertainer, or a sports hero? Why?

Video Activity: Modeling: Learning by Observation features the original footage of Bandura’s famous experiment.

SUMMING UP Unlike Freud and Erikson, behaviorists emphasize that psychologists should study what can be observed and measured, not the unconscious. Behaviorists also thought that every behavior is the product of learning, and they set out to understand the laws of learning. Pavlov’s experiment with dogs (classical conditioning) and Skinner’s experiments with rats and pigeons (operant conditioning) demonstrated that learning is a lifelong process that guides human behavior. Social learning theorists extended behaviorism to include learning through the observation and imitation (modeling) of other people.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 2.8

XnDunO6KJp0eWgOspYrK5FwTeeErqloegcPeUJZsdIY1ZmBKf4nsQZGWGAg=Psychology should only study observable behavior. Behaviorists study how people learn and acquire habits through conditioning.Question 2.9

mIFFDOQ3aFjxM8xJKS+eCwQp/PmMgK3qai+gacpeAXqJdJTGzdwI9GAvvOQlaiGzqQMpx2dsF+fE/quKbcNBrGtSdouG9DnDnFdzmAeUdSE=We tend to associate white clothing with medical professionals. One specific example of classical conditioning is called the white coat syndrome, which occurs in people for whom past experiences with medical professionals (who wore white coats) conditioned anxiety. For that reason, when someone dressed in white takes their blood pressure, it is higher than it would be under normal circumstances. White coat syndrome is apparent in about half of the U.S. population over age 80. It began when those elders were children. Today many nurses, especially in pediatrics, wear colorful blouses and many doctors wear street clothes. They dress to prevent conditioned anxiety.Question 2.10

di5KayoiGIhHX0zU1kWRaJcSmN547PBcLN+Nt5Tvtk1ZsjQsB8tRhjBzTA2YEYgJatfFvfpmhRD++cfKOxGF0QOnMIxar0vyluOwSjFQGVUucO8d2rxYt89x7DXdElnAZf75Rg==Consequences that increase the frequency or strength of a particular action are called reinforcers in a process called reinforcement. Pleasant consequences are sometimes called rewards, but behaviorists do not call them that because what some people consider a reward may actually be a punishment, or an unpleasant consequence.Question 2.11

OweqQ7av/IGxhtTBevap59pAeAJhfWQyTFfVGd84/S+WN+dDq+RNhWVbizxPpWu7k/5TnHQ/Bi2BjdePji3EUpDUh9/cGVNpLe/uOQ==Generally, modeling is most likely to occur when the observer is uncertain or inexperienced (which explains why modeling is especially powerful in childhood) and when the model is admired, powerful, nurturing, or similar to the observer.