Brain and Emotions

Brain maturation is involved in the developments just described because all reactions begin in the brain (Johnson, 2011). Experience promotes specific connections between neurons and emotions.

Links between expressed emotions and brain growth are complex and thus difficult to assess and describe (Lewis, 2010). Compared with the emotions of adults, discrete emotions during early infancy are murky and unpredictable. The growth of synapses and dendrites is a likely explanation for the gradual refinement and expression of discrete emotions, the result of past experiences and ongoing maturation.

Growth of the Brain

Many specific aspects of brain development support social emotions (Lloyd-

208

Cultural differences become encoded in the infant brain, called “a cultural sponge” by one group of scientists (Ambady & Bharucha, 2009, p. 342). It is difficult to measure exactly how infant brains are molded by their context, in part because parents are reluctant to allow the brains of their normally developing infants to be scanned.

One study (Zhu et al., 2007) of adults—

Researchers consider this United States-

Beyond culture, an infant’s brain activity interacts with caregiver responses, probably in the first months of life as well as through the years of childhood (Nelson et al., 2014). Highly reactive 15-

Learning About Others

The tentative social smile of 2-

Social preferences form in the early months, connected not only with a person’s face, but also with voice, touch, and smell. Early social awareness is one reason adopted children ideally join their new parents in the first days of life (a marked change from 100 years ago, when adoptions began after age 1).

Social awareness is also a reason to respect an infant’s reaction to a babysitter: If a 6-

Every experience that a person has—

Serotonin not only increased momentary pleasure (mice love being licked) but also started a chain of epigenetic responses to reduce cortisol from many parts of the brain and body, including the adrenal glands. The effects on both brain and behavior are lifelong for mice and probably for humans as well.

209

For many humans, social anxiety is stronger than any other anxieties. Certainly to some extent this is genetic. But epigenetic research finds environmental influences important as well. This was clearly shown in a longitudinal study of 1,300 adolescents (twins and siblings): Their genetic tendency toward anxiety was evident at every age, but life events affected how strong that anxiety was felt (Zavos et al., 2012).

A smaller study likewise found that if the infant of an anxious biological mother is raised by a responsive adoptive mother who is not anxious, the inherited anxiety does not materialize (Natsuaki et al., 2013). Parents need to be comforting (as with the nuzzled baby mice) but not overprotective. Fearful mothers tend to raise fearful children, but fathers who offer their infants exciting but not dangerous challenges (such as a game of chase, crawling on the floor) reduce later anxiety (Majdandžić et al., 2013).

Stress

Emotions are connected to brain activity and hormones, but the connections are complicated; they are affected by genes, past experiences, hormones, and neurotransmitters not yet understood (Lewis, 2010). One link is clear: Excessive fear and stress harms the developing brain. The hypothalamus (discussed further in Chapter 8), in particular, grows more slowly if an infant is often frightened.

Brain scans of children who were maltreated in infancy show abnormal responses to stress, anger, and other emotions later on, including to photographs of frightened people. Some children seem resilient, but many areas of the brain (the hypothalamus, the amygdala, the HPA axis, the hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex—

Since early caregiving affects the brain lifelong, caregivers need to be consistent and reassuring. This is not always easy. Remember that some infants cry inconsolably in the early weeks. As one researcher notes:

An infant’s crying has 2 possible consequences: it may elicit tenderness and desire to soothe, or helplessness and rage. It can be a signal that encourages attachment or one that jeopardizes the early relationship by triggering depression and, in some cases, even neglect or abuse.

[J. S. Kim, 2011, p. 229]

Sometimes mothers are blamed, or blame themselves, when an infant cries. This attitude is not helpful: A mother who feels guilty or incompetent may become angry at her baby, which leads to unresponsive parenting, an unhappy child, and then hostile interactions. Presumably the results would be the same if the father, or grandmother, were the primary caregiver, although extensive research on those infant-

But the opposite may occur if early crying produces solicitous parenting. Then, when the baby outgrows the crying, the parent–

Synesthesia

Brain maturation may affect an infant’s ability to differentiate emotions—

210

Synesthesia seems more common in infants because the boundaries between the sensory parts of the cortex are still forming (Walker et al., 2010). Textures seem associated with vision, sounds with smells, and the infant’s own body seems connected to the bodies of others.

Video: Temperament in Infancy and Toddlerhood@2016 MACMILLAN

These sensory connections allow cross-

The tendency of one part of the brain to activate another may also occur for emotions. An infant’s cry can be triggered by pain, fear, tiredness, surprise, or excitement; laughter can turn to tears. Discrete emotions during early infancy are more difficult to recognize, differentiate, or predict than the same emotions in adulthood; infant emotions erupt, increase, or disappear for unknown reasons (Camras & Shutter, 2010). Brain immaturity is a likely explanation.

Temperament

Temperament is defined as the “biologically based core of individual differences in style of approach and response to the environment that is stable across time and situations” (van den Akker et al., 2010, p. 485). “Biologically based” means that these traits originate with nature, not nurture.

Confirmation that temperament arises from the inborn brain comes from an analysis of the tone, duration, and intensity of infant cries after the first inoculation, before much experience outside the womb. Cry variations at this very early stage correlate with later temperament (Jong et al., 2010).

Temperament is not the same as personality, although temperamental inclinations may lead to personality differences. Generally, personality traits (e.g., honesty and humility) are learned, whereas temperamental traits (e.g., shyness and aggression) are genetic. Of course, for every trait, nature and nurture interact.

The New York Longitudinal Study

In laboratory studies of temperament, infants are exposed to events that are frightening or attractive. Four-

These categories originate from the New York Longitudinal Study (NYLS). Begun in the 1960s, the NYLS was the first large study to recognize that each newborn has distinct inborn traits (Thomas & Chess, 1977). According to the NYLS, by 3 months, infants manifest nine traits that cluster into the four categories just listed.

211

Although the NYLS began a rich research endeavor, its nine dimensions have not held up in later studies. Generally, only three (not nine) dimensions of temperament are found (Hirvonen et al., 2013; van den Akker et al., 2010; Degnan et al., 2011), each of which affects later personality and school performance. The following three dimensions of temperament are apparent:

Especially for Nurses Parents come to you with their fussy 3-

It’s too soon to tell. Temperament is not truly “fixed” but variable, especially in the first few months. Many “difficult” infants become happy, successful adolescents and adults, if their parents are responsive.

Effortful control (able to regulate attention and emotion, to self-

soothe) Negative mood (fearful, angry, unhappy)

Exuberant (active, social, not shy)

Each of these dimensions is associated with distinctive brain patterns as well as behavior, with the last of these (exuberance versus shyness) most strongly traced to genes (Wolfe et al., 2014).

Since these temperamental traits are apparent at birth, some developmentalists seek to discover which alleles affect specific emotions (M. H. Johnson & Fearon, 2011). For example, researchers have found that the 7-

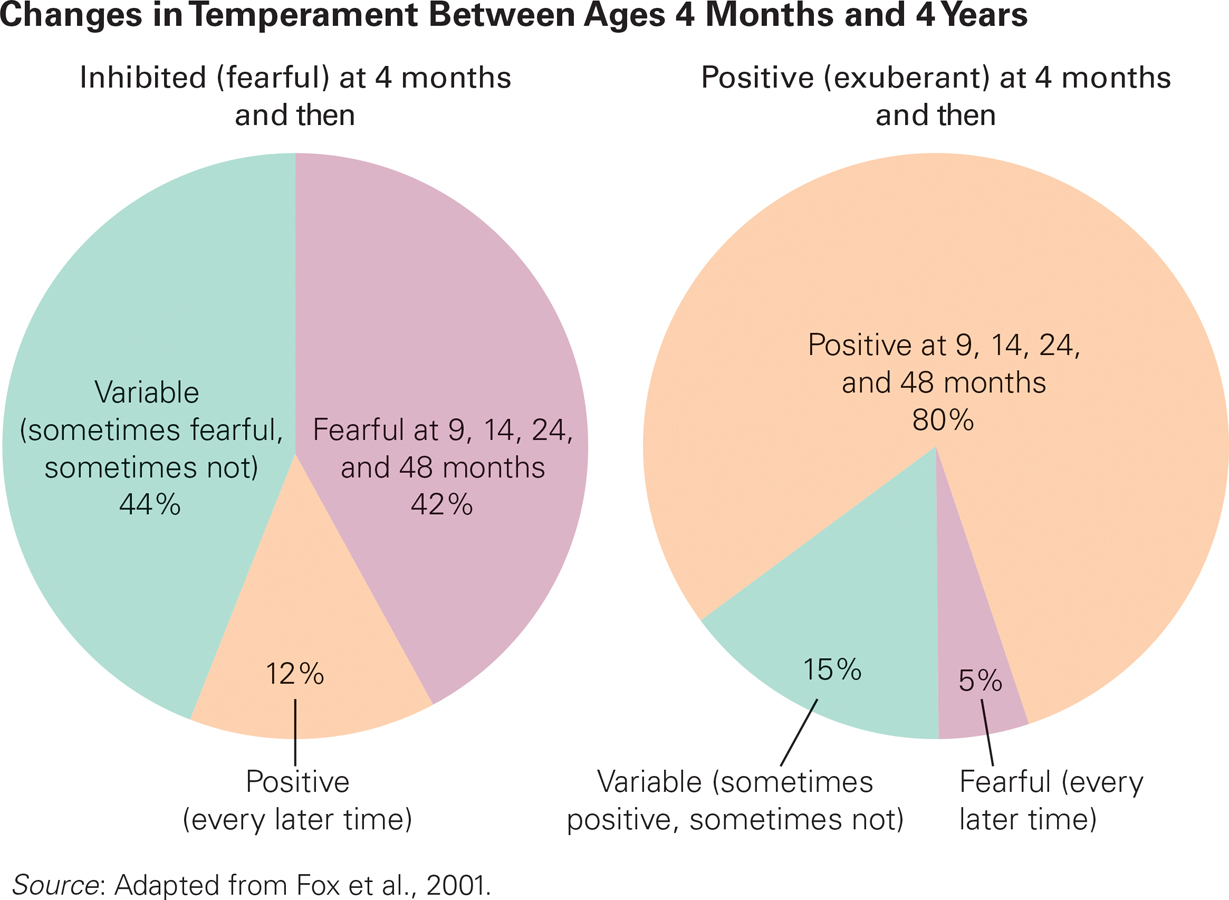

One longitudinal study analyzed temperament in the same children at 4, 9, 14, 24, and 48 months and in middle childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The scientists designed laboratory experiments with specifics appropriate for the age of the children; collected detailed reports from the mothers and later from the participants themselves; and gathered observational data and physiological evidence, including brain scans. Past data were reevaluated each time, and cross-

Half of the participants did not change much over time, reacting the same way and having similar brain-

Do Babies’ Temperaments Change? It is possible—

The researchers found unexpected gender differences. As teenagers, the formerly inhibited boys were more likely than the average adolescent to use drugs, but the inhibited girls were less likely to do so (L. R. Williams et al., 2010). The most likely explanation is cultural: Shy boys seek to become less anxious by drinking alcohol, smoking marijuana, or snorting cocaine, but shy girls may be more accepted as they are, or more likely to obey their parents.

Examination of these children in adulthood found intriguing differences between brain and behavior. Those who were inhibited in childhood still showed, in brain scans, evidence of their infant temperament. That confirms that biology affected their traits. However, learning (specifically cognitive control) was evident: Their behavior was similar to those with a more outgoing temperament, unless other factors caused serious emotional problems. Apparently, most of them had learned to override their initial temperamental reactions—

Continuity and change were also evident in another study that found that angry infants were likely to make their mothers hostile toward them, and, if that happened, such infants became antisocial children. However, if the mothers were loving and patient, despite the difficult temperament of the children, hostile traits were not evident later on (Pickles et al., 2013).

212

Other studies confirm that difficult infants often become easier—

The two patterns evident in all these studies—

Goodness of Fit

All the research finds that traces of childhood temperament endure, blossoming into adult personality, but all the research also confirms that innate tendencies are only part of the story. Context always shapes behavior. Ideally, parents find a goodness of fit—that is, meshing infant temperament and parent personality to allow smooth infant–

However, not only does infant temperament vary, parental temperament varies as well. One study found that parents who claimed goodness of fit between themselves and their infant were likely to be better parents, even when such obvious correlates as education were taken into account (Seifer et al., 2014). Obviously, adults need to adjust to babies more than vice-

Childhood temperament is linked to the parents’ genes and their personalities, which often are assessed using five dimensions, called the Big Five—openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Adults who are high in extroversion (surgency), high in agreeableness (effortful control), and low in neuroticism (negative mood) tend to be warmer and more competent parents (de Haan et al., 2009).

213

SUMMING UP Brain maturation underlies much of emotional development in the first two years. The circumstances of an infant’s life affect emotions and sculpt the brain, with long-

Temperament is inborn, with some babies much easier and others more difficult, some more social and others more shy. Such differences are partly genetic and therefore lifelong, but caregiver responses channel temperament into useful or destructive traits.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 7.6

rDbzF8HU8ZyxeE3NvI4l8/xtUnr1r3cILqqeuqzfHo7FoP63rtrdgPeA/fwXoeD5hr9CZX18iNqq6e/R0ra4rfc9WTBy2eptweJBH4pW4sc=The social smile, laughter, fear, self–awareness, and anger appear as the cortex matures. The maturation of the anterior cingulate gyrus (a part of the cortex) is directly connected to emotional self– regulation, allowing a child to hide or express his or her feelings. What is unknown is how infant brains are molded by their environment and culture and how this affects their expression of emotions. Question 7.7

/lTOJ040cc7GCLqzT0g+EEpfSTEfoN+EuIkLr6FCTb8vZE1pZ0DkCUi9Cn32pZeZaKLRog==Excessive stress harms the developing brain. The hypothalamus, in particular, grows more slowly if an infant is often frightened.Question 7.8

Zpx0UIX7cAzart0yd8GB6MFgP6TavF4u5rhH7vyBKk55IOxCHpfvhsgLybwzwAc+FceYx3FHajbgVz+ISynesthesia is phenomenon in which one sense triggers another in the brain. For older children and adults, the most common form of synesthesia is when a number or letter evokes a vivid color. Among adults, synesthesia is unusual. Synesthesia seems more common in infants because the boundaries between the sensory parts of the cortex are still forming. Textures seem associated with vision, sounds with smells, and the infant's own body seems connected to the bodies of others. These sensory connections allow cross–modal perception, when a sensation from one mode (such as a sound) is also experienced in another mode (such as sight).

A caregiver's smell and voice may evoke a vision of that person, for instance, or a sound may be connected with a shape. The tendency of one part of the brain to activate another may also occur for emotions. An infant's cry can be triggered by pain, fear, tiredness, surprise, or excitement; laughter can turn to tears. Discrete emotions during early infancy are more difficult to recognize, differentiate, or predict than the same emotions in adulthood; infant emotions erupt, increase, or disappear for unknown reasons. Brain immaturity is a likely explanation.Question 7.9

B75zyRrs98BEhh127rlURRjhK9HclQwf48iquxAsC/KFbIcr0eTaOvBDdTZwgRFG+crZerhMaX2k65tZariG6sfNAQM=Continuity and improvement are patterns of temperament found in nearly all studies. One longitudinal study analyzed temperament in the same children at 4, 9, 14, 24, and 48 months and in middle childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Half of the participants did not change much over time, reacting the same way and having similar brain–wave patterns when confronted with frightening experiences. Curiously, the participants most likely to change from infancy to age 4 were the inhibited, fearful ones. Least likely to change were the exuberant babies. Examination of these children in adulthood found intriguing differences between brain and behavior. Those who were inhibited in childhood still showed in brain scans evidence of their infant temperament. That confirms that biology affected their traits. However, learning (specifically cognitive control) was evident: Their behavior was similar to those with a more outgoing temperament, unless other factors caused serious emotional problems. Apparently, most of them had learned to override their initial temperamental reactions— not to erase their innate impulses, but to keep them from impairing adult action. Question 7.10

Y3GNggi/zwQT5MpHXXhVFeT89T3GNKnZexWgjmwTnhmcKyIXpA19lWN/Yw2XqemfTRspwQ==The two patterns evident in all studies—continuity and improvement— have been replicated in many longitudinal studies of infant temperament, especially for antisocial personality traits. Difficult babies tend to become difficult children, but family and culture sometimes mitigate negative outcomes. Context always shapes behavior. Ideally, parents find a goodness of fit— that is, meshing infant temperament and parent personality to allow smooth infant– caregiver interactions. With a good fit, parents of difficult babies build a close and affectionate relationship; parents of exuberant infants learn to protect them from harm; parents of slow– to– warm– up toddlers encourage them while giving them time to adjust.