Infant Day Care

Cultural variations in allocare are vast. Each theory just described can be used to justify or criticize variations. No theory directly endorses any particular position. Nonetheless, theories are made to be useful, so we include some implications of various theories in our discussion.

Many Choices

It is estimated that about 134 million babies will be born each year from 2010 to 2021 (United Nations, 2013). Most newborns are cared for primarily or exclusively by their mothers; allocare increases as the baby gets older. Fathers and grandmothers typically provide care as well. Daily care by a non-

For instance, virtually no infant in some of the poorest nations receives regular non-

231

As discussed previously, fathers worldwide increasingly take part in baby care. However, some cultures still expect fathers to stay at a distance and others favor equality (Lamb, 2013).

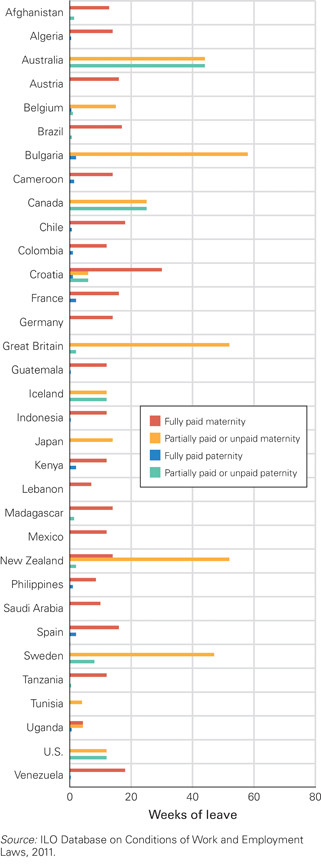

Most nations provide some paid leave for mothers who are in the workforce. Some also provide paid leave for fathers, and several nations provide paid family leave that can be taken by either parent or shared between them. The length of paid leave varies from a few days to about 15 months (see Figure 7.3). Laws in many nations guarantee that a mother’s job will be open to her when her leave is over.

A Changing World No one was offered maternity leave a century ago because the only jobs that mothers had were unregulated. Now, virtually every nation has a maternity leave policy, revised every decade or so. As of 2012, only Australia, Iceland, and Canada offered policies reflecting gender equality. That may be the next innovation in many nations.

Note: In some cases, leave can be shared between parents or other family members. Many nations have increased leave in the past three years.

Some concern about job security and shared care arises from humanism, which values the well-

Since behaviorists emphasize learning, they seek to ensure that every baby has the proper experiences, whether provided by the mother or by someone else. One popular effort to ensure this is to send trained visitors to mothers of infants at home. They provide toys, books, and advice, encouraging caregiver–

Uncertainty About What is Best

There is no agreed-

Many people believe that the practices of their own family or culture are best and that other patterns harm either the infant or the mother. This is another example of the difference-

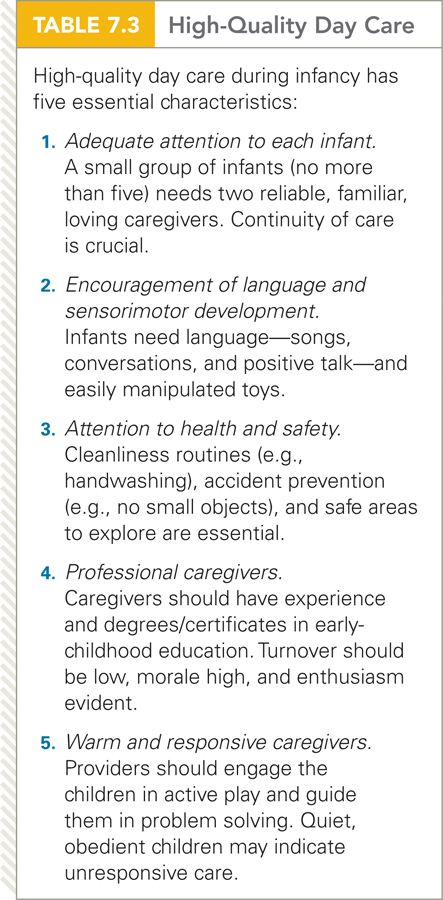

Center care is scarce in South Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Many parents believe it is harmful. (Table 7.3 lists five essential characteristics of high-

OBSERVATION QUIZ What three cultural differences do you see in the pictures above?

The Bangladeshi children are dressed alike, are the same age, and are all seated around toy balls in a net—

232

Most nations are between those two extremes. One example comes from Australia, where the government has recently attempted to increase the birth rate. Parents are given $5,000 for each newborn, parental leave is paid, and public subsidies provide child-

Parents are caught in the middle. For example, one Australian mother of a 12-

Especially for Day-

Reassure the mother that you will keep her baby safe and will help to develop the baby’s mind and social skills by fostering synchrony and attachment. Also tell her that the quality of mother–

I spend a lot of time talking with them about his day and what he’s been doing and how he’s feeling and they just seem to have time to do that, to make the effort to communicate. Yeah they’ve really bonded with him and he’s got close to them. But I still don’t like leaving him there. And he doesn’t, to be honest…. Because he’s used to sort of having, you know, parents.

[quoted in Boyd et al., 2013]

Underlying every policy and practice are theories about what is best. In the United States, marked variations are apparent by state and by employer, with some employers far more generous than the law requires. Almost no company pays for paternal leave, with one exception: The U.S. military allows 10 days of paid leave for fathers.

In the United States, only 20 percent of infants are cared for exclusively by their mothers (i.e., no other relatives or babysitters) throughout their first year. This is in contrast to Canada, which is similar to the United States in ethnic diversity but has far more generous maternal leave and lower rates of maternal employment. In the first year of life, most Canadians are cared for only by their mothers (Babchishin et al., 2013). Obviously, these differences are affected by culture, economics, and politics more than by any universal needs of babies.

The home visiting programs that help some novice mothers do not always have the desired effects (Paulsell et al., 2014), and grandmother care, informal care, and center care have each sometimes been destructive. For example, in most nations and centuries, infants were more likely to survive if their grandmothers were nearby, especially when they were newly weaned (Sear & Mace, 2008). The hypothesis is that grandmothers provided essential nourishment and protection. But in one era (northern Germany, 1720–

Mixed evidence can also be found for center care, as the following A View from Science explains.

233

a view from science

The Mixed Realities of Center Day Care

A professional organization, the National Association for the Education of Young Children, recently revised its standards for care of babies from birth to 15 months, based on current research (NAEYC, 2014). Breast-

Many specific practices are recommended to keep infant minds growing and bodies healthy. For instance, “before walking on surfaces that infants use specifically for play, adults and children remove, replace, or cover with clean foot coverings any shoes they have worn outside that play area. If children or staff are barefoot in such areas, their feet are visibly clean.” Another recommendation is to “engage infants in frequent face-

Such responsive care, unfortunately, has not been routine for infants, especially those not cared for by their mothers. A large study in Canada (Côté et al., 2008) found that infant girls seemed to develop equally well in various care arrangements. However, boys from high-

The opposite was true for boys from low-

Research in the United States has also found that center care benefits infants of low-

The social consequences were less stellar, however. Most analyses find that secure attachment to the mother was as common among infants in center care as among infants cared for at home. Like other, smaller studies, the NICHD research confirms that the mother–

However, infant day care seemed detrimental when the mother was insensitive and the infant spent more than 20 hours a week in a poor-

More recent work finds that high quality care in infancy benefits the cognitive skills of children of both sexes and all income groups, with no evidences of emotional harm, especially when it is followed by good preschool care (Li et al., 2013). This raises another question: Might changing attitudes and female employment, and centers that reflect new research on infant development (as expressed in the NAEYC standards above) produce more positive results from center care? Or is there something about the connection between mother and baby that evolved over the millennia, as evolutionary theory might posit, that makes mother care better for infants than allocare?

A Stable, Familiar Pattern

No matter what form of care is chosen or what theory is endorsed, individualized care with stable caregivers seems best (Morrissey, 2009). Caregiver change is especially problematic for infants because each simple gesture or sound that a baby makes not only merits an encouraging response but also requires interpretation by someone who knows that particular baby well.

For example, “baba” could mean bottle, baby, blanket, banana, or some other word that does not even begin with b. This example is an easy one, but similar communication efforts—

A related issue is the diversity of baby care providers. Especially when the home language is not the majority language, parents hesitate to let people of another linguistic background care for their infants. That is one reason that, in the United States, immigrant parents often prefer care by relatives instead of by professionals (Miller et al., 2014). Relationships are crucial, not only between caregiver and infant, but also between caregiver and parent (Elicker et al., 2014).

234

Particularly problematic is instability of non-

As is true of many topics in child development, questions remain. But one fact is without question: Each infant needs personal responsiveness. Someone should serve as a partner in the synchrony duet, a base for secure attachment, and a social reference who encourages exploration. Then infant emotions and experiences—

SUMMING UP The psychosocial impact of infant day care depends on many factors, including the culture. Although many nations pay mothers of infants to stay home with their babies, maternal employment does not seem harmful if someone else provides responsive care. Continuity is crucial; mothers, fathers, and others can all be good caregivers.

Cultures vary greatly not only in whether they provide paid child care, but whether they approve of such care. The United States tends to favor maternal care over center care but makes it difficult for families to survive without maternal employment.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 7.25

/z1ybMCrDq5PB9tgZOUI91EBpSeqzA94R+buQEEMI8an0yHE9elxO0ZJVlic54SkRkhOcdjylyU=Advantages of nonmaternal care include that it allows mothers to return to work, and provides (in good environments) safe spaces, appropriate learning and playing equipment, and trained providers to interact with children. The advantages appear most obvious around preschool age; debate remains about its value for younger children.Question 7.26

LMihwlgIGy+K3y4kPqwvTCxIIXAy3of0UiKscs8HDuD/gjk75LmbrZF0ehz/JuUKBIylrA==Disadvantages vary greatly by type of care, and the range of quality in care is certainly an issue. There is some correlation between later aggression and early nonmaternal care. Family income level, culture, religion, education levels, and even the sex and temperament of the child all play a role in determining what type of care is best for a child.Question 7.27

uiZlHxjk+5X3XJFYjrDUfPXaTB2QCrfcm9PEFgA2sQhXH2CVa5PjTsQVPz6dauhRxH0AcAlQV3qps2uYFON3/m62CIcEfljEjpb6GOQKZw9q5+8IA large study in Canada found that infant girls seemed to develop equally well in various care arrangements. However, boys from high–income families with allocare fared less well than similar boys whose mothers provided all their care. By age 4, those who had been in day care were slightly more assertive or aggressive, with more emotional problems (e.g., a teacher might note that a kindergarten boy “seems unhappy”). The opposite was true for boys from low– income families: On average, they benefited from nonmaternal care, again according to teacher reports. The researchers insist that no policy implications can be derived from this study, partly because care varied so much in quality, location, and provider. Question 7.28

xQgu0DAeI0RY9/VP6omR1F+RZ8zXSU1HWtWfWiihbeAkg0AF74mswDS+E+yLeALUAant6Lf3/RVGxorU/46xebCXncCGvlPZE87xSlffb7il69CKVariations in day care arrangements are vast, and not all—particularly those that rely on family assistance— have records that make study and evaluation possible. The quality of infant day care varies a great deal, and some babies seem far more affected than others by the quality of the care they receive. In addition, there continues to be disagreement about the wisdom of nonmaternal child care for the very young.

235