12.2 Health Habits and Age

Each person’s routines of daily life powerfully affect their susceptibility to diseases and chronic conditions; this applies both to current routines and to those that have been in place since childhood. It is particularly true for problems associated with aging—

ESPECIALLY FOR Doctors and Nurses If you had to choose between recommending various screening tests and recommending various lifestyle changes to a 35-

Consider cancer, the leading cause of death for adults aged 25 to 65. The risk of cancer increases with every year of life, but lifestyle, not age, is usually the underlying cause. According to one estimate, 30 percent of cancer cases are caused by smoking, 30 percent by diet, and 5 percent by inactivity (Willett & Trichopoulos, 1996).

Of course, the specific lifestyle effects on susceptibility vary with each disease, even each type of cancer, and uncontrollable factors, primarily genetic, play a major role in some diseases and a minor role in others. However, people can cut in half their overall morbidity and mortality during adulthood (ages 25 to 65) if they have healthy habits.

To clarify this, it is important to know the various ways in which health is measured:

- Mortality means death.

- Morbidity means disease, the rates of which depend partly on diagnosis.

- Disability, the usual result of morbidity, is the inability to do something that people usually can do. For example, one form of morbidity is glaucoma; this could mean serious disability if a person can see only shapes, but less serious disability if the person cannot read without glasses.

- Vitality—also known as life force, or joie de vivre—may be the most important, but it is the most difficult to measure. Some people with morbid conditions that increase disability and the risk of mortality are nonetheless happy and active.

The goal of good health habits is not only to reduce illness, but also to increase wellness so that adults can live for decades at full vitality.

Tobacco and Alcohol

Many teenagers believe that smoking and drinking make them cool and signify maturity. Nicotine also provides an energy boost, which seems to be an indicator of health. Accordingly, many young people pick up those habits as soon as they can, legally or not.

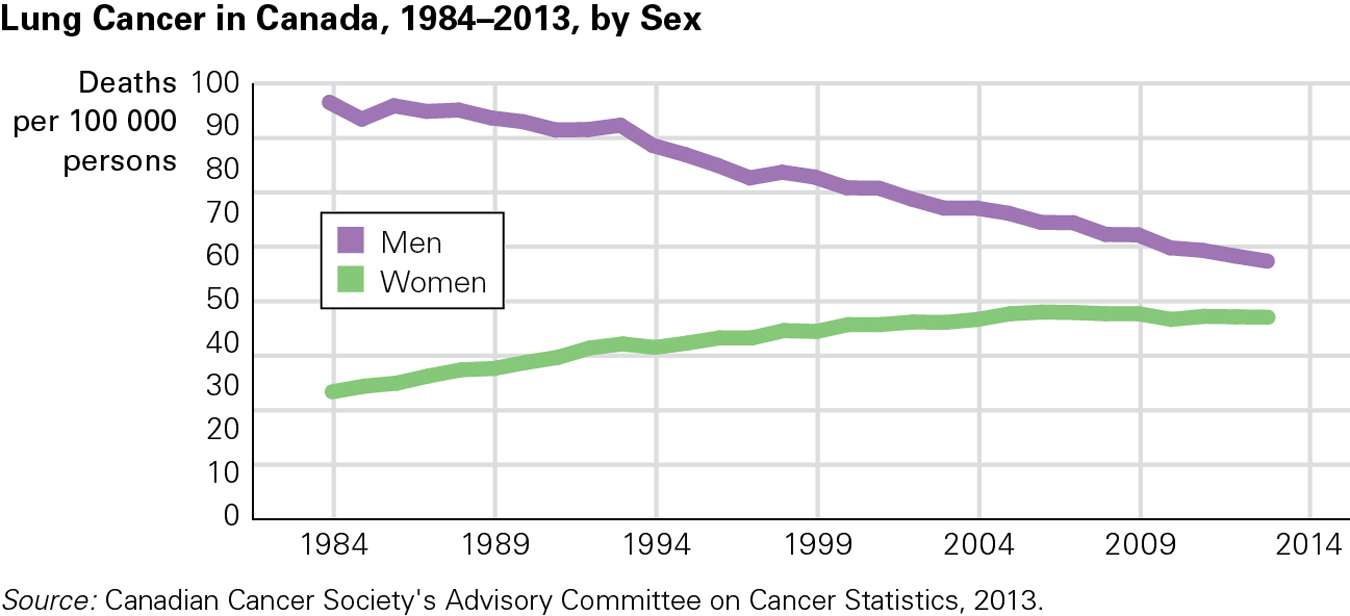

Even though many people eventually quit smoking, they are still at greater risk for developing cancer. We now know that cancer deaths reflect smoking patterns of years earlier. Canadian men have been quitting smoking for decades. As a result, the incidence of lung cancer among men levelled off in the 1980s and then began declining (see Figure 12.2). Conversely, smoking among women has increased over time. As a result, lung cancer rates for women started increasing in 1982 and then went up significantly, by a rate of 1.1 percent a year between 1998 and 2007, before levelling off. Even so, the incidence of lung cancer is still higher among Canadian men (60 per 100 000) than women (47 per 100 000) (Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics, 2013).

437

While rates of smoking and lung cancer deaths are decreasing in countries such as Canada and the United States, they are rising in other countries, such as China, India, and Indonesia, especially among women. For instance, in these countries, more than half of the men are smokers as are just less than 10 percent of the women. The World Health Organization calls tobacco the single largest preventable cause of death and chronic disease (Blas & Kurup, 2010).

The harm from cigarettes is dose-

However, moderation is impossible for some. Alcoholics may find it easier to abstain than to have one, and only one, drink a day. Higher amounts of drinking destroys brain cells; contributes to osteoporosis; decreases fertility; accompanies many suicides, homicides, and accidents; destroys families; and increases the risk of 60 diseases, not only of the liver but also of the breasts, stomach, and throat (Hampton, 2005).

Alcoholism increases with poverty and causes disproportionate harm in poorer countries (Grimm, 2008) because prevention, treatment, and enforcement strategies have not caught up with abuse. In general, low-

Homeostasis and allostasis may be factors: Poverty reduces the sources of pleasure and increases stress, so temporary joy comes from smoking and drinking. But then more nicotine and alcohol become needed because of homeostasis, and, over the long term, addiction begins, joy declines, and life ends (Sterling, 2012). Momentary vitality becomes morbidity and then mortality.

Overeating

Metabolism decreases by one-

A Worldwide ProblemObesity is now recognized as a major health problem in many nations. Cultural solutions—

Statistics Canada reports that in 2012, 60 percent of males 18 years and older were either overweight or obese, as were 45 percent of women. Overall, slightly more than 18 percent of adult Canadians qualified as obese. The authors of this report caution that these are self-

438

In the United States, the rates are even more alarming. There, 65 percent of adults are overweight, with a body mass index (BMI) above 25. More than half of those overweight people are obese (with a BMI of 30 or more), and 6 percent overall are morbidly obese (with a BMI of 40 or more) (Flegal et al., 2012). Rates in the other North American nation, Mexico, are also high.

Excess weight increases the risk of every chronic disease, but the most glaring example is diabetes, which affects twice as many North Americans currently as it did 40 years ago (Taubes, 2009). The direct cause is insulin resistance (where the body fails to respond to its own insulin), which, left untreated, can lead to death. Diabetes also causes eye, heart, and foot problems.

Sadly, partly because of how they are treated, obese adults avoid socializing, exercising, and going for medical checkups. As a result, their morbidity increases far more than their weight alone would predict (Puhl & Heuer, 2010).

Solutions to the Obesity EpidemicStopping any addiction is difficult because long-

Diet drugs are one traditional option; however, many have been found to cause cardiovascular and digestive problems, or to lead to addiction. Gastric bypass surgery causes dramatic weight loss in many patients, but as with all surgical procedures, there are risks. The risks may be worth it though, since morbidly obese people have higher death rates without surgery than with it (Schauer et al., 2010).

Drugs and surgery are not enough: Patients must change their lifestyle to accommodate new eating habits and exercise. People who are highly motivated and long past adolescence and emerging adulthood are much more likely to follow through with those required lifestyle changes. For those morbidly obese teenagers who undergo surgery, the adjustments may be particularly difficult (Widhalm et al., 2011).

Developmentalists emphasize that early prevention is more effective than medical remedies. You have already read that babies born underweight often become fat children, who may become overweight adults. At that point, the stigma and discrimination experienced by obese people can have an adverse effect on their health, both psychological as well as physical (Puhl & Heuer, 2010).

Inactivity

Regular exercise protects against illness even if a person is overweight or a smoker. When any habit changes for the better, a daily hour of exercise is the best predictor of maintaining the change (Shai & Stampfer, 2008). Specific benefits of exercise include lower blood pressure, stronger hearts and lungs, and reduced risk of almost every disease, including depression, diabetes, osteoporosis, heart disease, arthritis, and even cancer. By contrast, sitting for long hours correlates with almost every unhealthy condition, especially heart disease and diabetes, both of which carry additional health hazards beyond the disease itself. Even a little movement—

439

Walking briskly for 30 minutes a day, five days a week, is a reasonable goal. More intense exercise (e.g., swimming, jogging, bicycling) is ideal. It is possible to exercise too much, but almost no adult aged 25 to 65 does. In fact, one study that used objective assessment of adult movement (electronic monitors) found that less than 5 percent of adults in the United States and England exercise even 30 minutes per day (Weiler et al., 2010). Self-

In 2010, about 52 percent of Canadians aged 12 and older reported that they were moderately active during their leisure time, which was equivalent to walking at least 30 minutes a day or engaging in a one-

The close connection between exercise and health, both physical and mental, is well known, as is the influence of family, friends, and neighbourhoods. Exercise-

Researchers are now trying to pin down specifics. Does the type of exercise matter (walking, gardening, swimming, running)? Is half an hour each day better than four hours on the weekend? These are unanswered questions, but no one doubts that adults should be active, year in, year out. Maintaining any healthy habit is the hardest part, as the following explains.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

A Habit Is Hard to Break

Every adult knows that smoking cigarettes, abusing alcohol, overeating, and remaining sedentary are harmful, yet many have at least one destructive habit. Why don’t we all shape up and live right? Breaking New Year’s resolutions; criticizing people whose bad habits are not our own; feeling guilty for consuming sweets, salt, fried foods, cigarettes, or alcohol; buying gym memberships that go unused or exercise equipment that becomes dust-

Social scientists have focused on this conundrum (Conner, 2008; Shumaker et al., 2009). They have found that changing a habit is a long, multi-

- denial

- awareness

- planning

- implementation

- maintenance.

The first step, denial, occurs because all bad habits exist for good reasons. For example, most cigarette smokers begin as teenagers because they seek social acceptance and/or weight control—

In fact, with many life-

Denial reduces stress, which leads people to deny what is obvious to others. They say, “I only drink on weekends,” or “It’s genetic,” or “Other people eat more.” Ideally, denial crumbles and the person moves to the next stage.

Awareness must be attained by the individual. Others help, not by accusing but by listening, either via motivational interviewing (encouraging the individual to describe the reasons why change is needed) or via acceptance and commitment therapy (recognizing the emotional aspects of the habit). Both motivational interviewing and commitment therapy begin with the person’s own values. This is crucial: Adults rebel when others tell them what to do, think, or believe (Bricker & Tollison, 2011).

440

Planning occurs only after the person is aware of the problem and wants to solve it. Planning is specific, with a set date for quitting and strategies to overcome obstacles. Care is needed at this step because humans tend to underestimate the power of their own impulses; this is true for smokers, dieters, and addicts of all kinds.

Such underestimating was evident in a particular experiment. Researchers gave students who were entering or leaving a college cafeteria their choice of several packaged snacks, promising them about $10 (and the snack) if they did not eat it for a week. Those who were entering, presumably aware of the demands of hunger and less certain of their ability to shrug off cravings, planned to avoid temptation by choosing a healthy snack. Most of them (61 percent) earned the money. However, those leaving the cafeteria apparently underestimated the power of hunger and overestimated their ability to battle cravings. They chose a more tempting snack and later ate it; only 39 percent earned the money (Nordgren et al., 2009). Planning has to take into account a person’s weakest moments: Most planners are too optimistic; counsellors can help turn awareness into a solid plan.

Implementation is quitting a harmful habit according to plan. One crucial factor is gathering social support, such as by (1) letting others know the date and the plan, (2) finding a buddy, or (3) joining a group (e.g., Weight Watchers, Alcoholics Anonymous, or SmokEnders). Engaging all three forms of social support is even better yet, since private efforts often fail.

Willpower is like a muscle: Putting too much stress on it for too long will make it break, but gradual strengthening is possible (Vohs & Baumeister, 2013). That means implementation is most successful when tackling one habit at a time: Quitting cigarettes when starting a diet is almost impossible; this double-

Maintenance is the most important step, yet the one that most people ignore. Although quitting may be difficult, many addicts experience the pain of quitting, get past the pain, and then relapse, only to quit again and again. Dieters gain and lose weight so often that this phenomenon has a name—

Maintenance is destroyed by overconfidence. People forget the power of temptation. The recovered alcoholic goes out with friends who drink, planning to order only juice; the dieter buys ice cream to offer to guests or for the rest of the family; the person who joined the gym skips a day, promising to make up for it the following day. Such actions are far more dangerous than people realize because they add stress. For instance, the dinner guests might not eat all the ice cream, and later, the stress of having resisted it earlier finally makes the ice cream all the more irresistible.

In another study, dieters who were given a stressful task (remembering a nine-

This is an example of attention myopia, when resolve (maintenance ability) momentarily fades. Attention myopia occurs with many self-

Accumulating Stressors

Stress is part of life, from birth to death. Between ages 25 and 65, everyone experiences major stress (e.g., the death of a family member), minor stress (e.g., a snowstorm), and daily hassles (e.g., traffic jams).

From Stress to Stressor Not every stress becomes a stressor, however. A stressor is any experience, circumstance, or condition that negatively affects a person. How people cope with stresses, making some become stressors and others not, affects their health.

Particularly if organ reserves are depleted or allostatic load is high, the physiological toll of major and minor stressors lowers immunity, increases blood pressure, speeds up the heart, reduces sleep, and produces many other reactions that lead to serious illness. A comprehensive review finds that stress clearly affects the whole body and that the best coping measures vary for each illness and each person (Aldwin, 2007). For instance, some patients recover better from surgery if they know details of their vital signs and healing; others just need to know that doctors are working to make them better.

441

For some, reactions to stressors can cause more stressors. For example, a longitudinal study of married couples in their 30s found that, if the husband’s health deteriorated, the chance of divorce increased. This was apparent with all couples, but it was particularly evident for well-

Age and Gender Psychologists distinguish between two major ways of coping. In problem-focused coping, people attack their problems (e.g., confront a difficult boss, move out of a noisy neighbourhood). In emotion-focused coping, people change their emotions (e.g., from anger to acceptance). In general, younger adults and adults of higher SES are more likely to attack problems, whereas older adults and those of lower SES try to accept them (Aldwin, 2007). This may indicate that those who are poorer and older believe that there is not much they can do to change their circumstances. A pessimistic attitude about the future is more common the less money one has (Robb et al., 2009).

Sex hormones may also affect responses to stress. Men are inclined to be problem-

Adults of both sexes and of every age and income level use both strategies, depending on the situation. The worst situation is to have no strategy at all—

Age brings another advantage. Emerging adulthood is a time of heightened aggravations (Aldwin, 2007). Once life settles down, some stresses (dating, job hunting, moving) are less frequent. Adults are more capable of arranging their lives to minimize the occurrence of stressors (Aldwin, 2007).

SES and Health Habits

Money and education protect health in every nation. According to Statistics Canada, less-

It is not obvious why this connection is so strong. Does education teach better health habits? Does income result in better medical care? Does high IQ added to high family SES in childhood allow more education, followed by living in better neighbourhoods, with less pollution and more opportunities to walk, bike, and play outside? Are wealthy people better able to insulate themselves from stressors because they can hire people to help them?

442

For whatever reason, the differences are dramatic. The 10 million U.S. residents with the highest SES outlive—

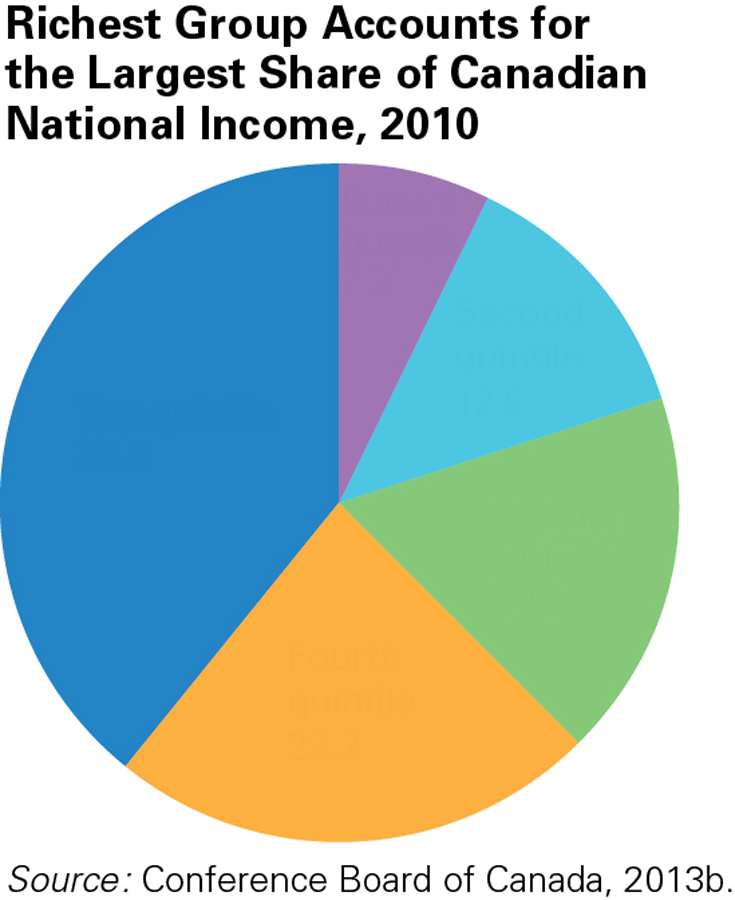

Although not as glaring as in the U.S., Canada’s income disparity is also at a record high. A recent report from the Conference Board of Canada (2013b) noted that not only did income inequality increase between 1990 and 2010, but since 1990, the richest group of Canadians has increased its total share of national income, while the poorest and middle-

SES is protective between nations as well as within them: Rich nations have less disease, injury, and death. For example, a baby born in 2010 in northern Europe can expect to live to age 79; in sub-

Diseases of affluenceCertain diseases, including diabetes, lung cancer, and breast cancer, were once called diseases of affluence because they were more common among the rich than the poor (Hu, 2011; Krieger, 2002, 2003) and in wealthier groups within each nation—

Distinguishing the effects of income, education, cohort, and culture is difficult because, as you remember from Chapter 1, all these factors overlap. For example, currently, African-

A recently proposed hypothesis is that low SES in the United States (and possibly in other parts of North America) leads to poor health habits—

Health of ImmigrantsData on immigrants complicate the connection between SES and health. Recent immigrants to both Canada and the United States tend to be healthier yet poorer than the native born: They have less heart disease, drug abuse, obesity, and so on than do their wealthier co-

One suggested explanation is that healthy people are more likely to emigrate; then their good health protects them even though they may be poor. Or, as Morton Beiser at the University of Toronto has noted, immigrants are healthier primarily because Canada has selection criteria that emphasize good health, and all potential immigrants must undergo a comprehensive medical screening (Beiser, 2005). All this may be true; however, the data find that the “healthy migrant” theory is not sufficient to explain immigrant health (Bates et al., 2008; Garcia Coll & Marks, 2011). Perhaps psychological or ethnic influences in low-

443

KEY points

- Mortality is increasingly uncommon in adulthood (ages 25 to 65): morbidity, disability, and loss of vitality remain problems.

- Smoking always harms health, but the effect of alcohol is harder to assess as it is beneficial in moderation and lethal in excess.

- Obesity and inactivity are increasing worldwide, leading to higher rates of many diseases, especially diabetes.

- People of different ages, genders, and incomes cope with stressors in varying ways.