14.2 Cognition

Ageism impairs elders in many ways, but the most insidious, and most feared, involves the mind, not the body. As with many stereotypes, it begins with a half-

The Aging Brain

New neurons form and dendrites grow in adulthood—

Slower and SmallerSenescence reduces production of neurotransmitters—

505

Brain slowdown can be a severe drain on the intellect because speed is crucial for many aspects of cognition. In fact, some experts believe that speed is the g mentioned in Chapter 12, the intellectual ability that underlies all other aspects of intelligence.

Although all scientists agree that reduced speed is a component of late-

In every part of the brain, the volume of grey matter (crucial for processing new experiences) is reduced. As a consequence, many people must use their cognitive reserve to understand events (Park & Reuter-

Variation in Brain EfficiencyAs is the case with changes to every other organ, all these aspects of brain senescence vary markedly from individual to individual. Although variability is obvious, the reasons are not. Higher education and vocational challenge correlate with less decline, either because keeping the mind active is protective or because such people began late adulthood with more robust and flexible minds (Gow et al., 2011; Salthouse, 2010).

Exercise, nutrition, and normal blood pressure are powerful influences on brain health, and all predict intelligence in old age. In fact, some experts contend that with good health habits and favourable genes, no intellectual decrement will occur (Greenwood & Parasuraman, 2012).

Using More of the BrainA curious finding from PET and fMRI scans is that, compared with younger adults, older adults use more parts of their brains, including both hemispheres, to solve problems. This may be selective compensation: Using only one brain region may be inadequate, so the older brain automatically activates more parts.

Consequently, on many tasks, older adults are as intellectually sharp as they always were. However, in performing difficult tasks that require younger adults to use all their cognitive resources, older adults are less proficient, perhaps because they already are using their brains to maximum capacity (Cappell et al., 2010).

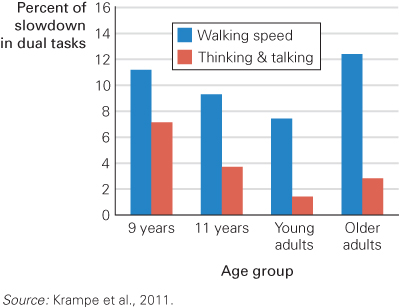

Brain shrinkage interferes with multi-

506

Information Processing After Age 65

Given the complexity and diversity of late life cognition, we need to examine specifics to combat general stereotypes. For this, the information-

InputProcessing information requires that sensations precede perception, yet as you just read, no sense is as sharp at age 65 as at age 15. Glasses and hearing aids mitigate most severe sensory losses, but more subtle deficits also impair cognition. Information must cross the sensory threshold, the divide between what is sensed and what is not, in order to be perceived. Sensory losses may not be recognized because the brain automatically fills in missed sights and sounds. People of all ages believe they look at the eyes of their conversation partner, yet a study that examined gaze-

Acute hearing is also needed to detect nuances of emotion. Older adults are less able to decipher the emotional content in speech, even when they hear the words correctly (Dupuis & Pichora-

OBSERVATION QUIZ

How much were the 9-

Nine-

MemoryThe second step of information processing is memory. Remember stereotype threat: If older people suspect their memory is fading, anxiety itself impairs memory, a phenomenon more apparent among those with more education (Hess et al., 2009), probably because they are quicker to notice it.

Here again, specifics are important to fight stereotypes. Some aspects of memory remain strong throughout late adulthood, including vocabulary, whereas others do not, such as memory for names. Thus, a person who cannot recall a name should not conclude that memory, overall, is fading.

One memory deficit is source amnesia—forgetting the origin of a fact, idea, or snippet of conversation. Source amnesia is particularly problematic with the information bombardment of television, radio, print, and the Internet. Elders may believe a rumour or political advertisement if they forget the source (Jacoby & Rhodes, 2006). Compensation would mean deliberate attention to the reason behind the message before accepting a televised ad or a con man’s promises.

Working memory, the memory of information held in the brain for a moment before processing (evaluating, calculating, and inferring), shrinks with age. Speed is critical here: Older individuals take longer to perceive and process sensations, and this reduces working memory because some items fade before they can be evaluated. A common test of working memory is repeating a string of digits backwards, but if the digits are said quickly, a slow-

507

Some research finds that when older people take their time and concentrate, their working memory may be as good as ever. For example, a study of reading ability found that although older people reread phrases more than younger people did, when allowed ample time the old and young were equally accurate in reading comprehension (Stine-

In Daily LifeEcological validity is the idea that ability should be measured in everyday tasks and circumstances, not as laboratory tests assess it. Ecological validity is particularly significant for the elderly, who are disadvantaged by traditional testing (Marsiske & Margrett, 2006).

Ecological validity in measuring the intellect begins with arranging the testing conditions so that optimal performance is assessed. For example, older adults are at their best in the early morning, when adolescents are half asleep. If both groups are tested at 8 a.m., or at 2 p.m., comparisons would reflect time of day, not just mental ability. Similarly, if basic intellectual ability is assessed via a timed test, then faster thinkers (usually young) would seem more capable than slower thinkers (usually old), even if the slower ones were more accurate, given a few more seconds to think.

A more fundamental ecological issue regards what should be assessed: pure, abstract thinking or practical, contextual thought. Traditional tests measure fluid cognitive abilities that are valued by the young, but the elderly are more adept at problem solving and emotional regulation. Those practical abilities may improve with age but are not traditionally measured.

Awareness of the need for ecological validity has helped scientists restructure research on memory, finding fewer deficits than originally thought. However, some tests may still overestimate or underestimate ability. For instance, how should we test long-

It is impossible to be totally objective in assessing memory. We know, at least, that stereotypes must be avoided, and global assessments are too simplistic. Not only do individuals vary, but some kinds of memory show marked age-

The final ecological question is “What is memory for?” Older adults usually think they remember well enough and, unless they develop a brain condition such as Alzheimer’s disease (soon to be described), they are correct: They remember how to live their daily lives, happily and independently.

Control ProcessesInstead of the analysis and forethought that characterize executive function, the elderly tend to rely on prior knowledge, general principles, familiarity, and rules of thumb in their decision making (Peters et al., 2011). They are less likely to use analytic reasoning and more likely to base conclusions on personal and emotional experience. As you remember from the discussion of dual processing in Chapter 9, experiential thinking is not always faulty, but sometimes analytical thinking is needed to control the impulses that arise from past experience.

508

Thus, the underlying impairment of cognition in late adulthood may be in control processes, which, as you read in Chapter 7, are the various methods used to regulate the analysis and flow of information from all parts of the brain. These include memory and retrieval strategies, selective attention, and rules or strategies for problem solving, all part of what is considered executive function. Control processes depend on the prefrontal cortex, which shrinks with age.

As mentioned, one control process is retrieval, which is crucial for analysis. Analysis involves retrieving thoughts and memories of past events and then recognizing the similarities and differences between these experiences and new challenges. Without access to these previous instances, the benefits of past experiences fade for elders.

Inadequate control processes may explain why many older adults have extensive vocabularies (measured by written tests) but limited fluency (when they write or talk), why they are much better at recognition than recall, why tip-

In a study that illustrated strategic retrieval, adults of varying ages were given props for 30 odd and memorable actions, such as kissing an artificial frog or stepping into a large plastic bag (Thomas & Bulevich, 2006). They were asked to perform 15 of these actions (and they did them), and they were told to imagine doing the other 15. Two weeks later, participants read a list of 45 actions (15 done, 15 imagined, and 15 new). They were asked which were performed, which were imagined, and which were new. Half the participants just read the list and answered performed/imagined/new; the other half were first guided in memory strategies that might help (asked to remember sensations, such as the feel of the frog as they kissed it).

Among the half who merely read the list, the younger adults assigned 78 percent of the items to the correct categories, whereas the older adults were correct only 52 percent of the time. As for the half who were taught memory strategies, the younger adults still got 78 percent correct, but the older ones were correct 66 percent of the time (Thomas & Bulevich, 2006). Thus, guidance in retrieval strategies was more helpful to the old than to the young.

Many gerontologists think elders would benefit from using control strategies, as in this example. Unfortunately, even though “a high sense of control is associated with being happy, healthy, and wise,” many older adults resist suggested strategies because they believe that declines are “inevitable or irreversible” and that no strategy could help (Lachman et al., 2009). Efforts to improve their use of control strategies are often discouraging (McDaniel & Bugg, 2012).

OutputThe final step in information processing is output. In the Seattle Longitudinal Study (described in Chapter 12), the measured output of all five primary mental abilities—

ESPECIALLY FOR People Who Are Proud of Their Intellect What can you do to keep your mind sharp all your life?

Overall, note that output is usually measured by various tests of production, validated by comparing the output of older adults with that of younger adults. As detailed in Chapters 7 and 12, intelligence tests were initially designed to measure success in school. Many of the questions are quite abstract, and many are timed, since speed of thinking correlates with intelligence for younger adults. A smart person is said to be a “quick” thinker, the opposite of someone who is “slow.” But abstractions and speed are exactly the aspects of cognition that fade most with age. Perhaps ecological validity, already described regarding memory tests, is especially crucial for output. Thus training that considers individual interests and abilities might increase the intellect. This possibility is being explored by many scientists, as the following describes.

509

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Learning Late in Life

Many people have tried to improve the intellectual abilities of older adults by teaching or training them in various tasks (Lustig et al., 2009; Stine-

Dr. Reza Naqvi of the University of Toronto reviewed more than 5000 studies from as far back as the 1960s and concluded that brain exercises based on computer programs or memory games were more effective than medications and vitamin supplements in maintaining older adults’ cognitive health (Naqvi et al., 2013). For example, in one part of the Seattle Longitudinal Study, 60-

Another group of researchers (Basak et al., 2008) targeted control processes. Volunteers, with an average age of 69 and no signs of neurocognitive disorder (all similar in cognition before the study began), were divided into an experimental group and a control group (all similar in cognition before the study began). None were video-

The experimental group was then taught to play a video game, set to begin at the easiest level. Participants enjoyed the game and tried to improve. After each game, they were told their score, and another game began—

Similar results have been found in many other training programs involving the young-

What about the old-

Many developmentalists are suspicious of the simple “use it or lose it” hypothesis, especially when it leads to many of the elderly doing newspaper puzzles (crosswords, mazes, Sudoku) to supposedly prevent neurocognitive impairment. However, they are not about to tell older people to stop trying to learn new skills. One researcher concluded, “[A]lthough my professional opinion is that…the mental-

510

KEY points

- The brain slows down in late adulthood, which impairs cognition.

- Variation is evident in late-

life intellectual ability, not only among people but also among abilities, with vocabulary particularly likely to stay or increase, and speed of thought and spatial abilities particularly likely to decrease. - Memory for names and places fades more quickly than memory overall.

- Impairment in control processes—

especially retrieval strategies— may underlie the cognitive deficits of old age.