3.4 Infant Cognition

The rapid physical growth of the human infant, just described, is impressive, but intellectual growth during infancy is even more awesome. Concepts and sentences—

Sensorimotor Intelligence

Piaget called cognition in the first two years sensorimotor intelligence because infants learn through their senses and motor skills. He subdivided this period into six stages (see TABLE 3.3).

| For an overview of the stages of sensorimotor thought, it helps to group the six stages into pairs. The first two stages involve the infant’s responses to its own body. | |

| Stage One (birth to 1 month) | Simple reflexes: sucking, grasping, staring, listening |

|

Stage Two (1- |

Primary circular reactions (the first acquired adaptations): accommodation and coordination of reflexes Examples: sucking a pacifier differently from a nipple; grabbing a bottle to suck it |

| The next two stages involve the infant’s responses to objects and people. | |

|

Stage Three (4- |

Secondary Circular Reactions (making interesting sights last): responding to people and objects Example: clapping hands when mother says “patty- |

|

Stage Four (8- |

Coordination of secondary circular reactions (new adaptation and anticipation): becoming more deliberate and purposeful in responding to people and objects Example: putting mother’s hands together in order to make her start playing patty- |

| The last two stages are the most creative, first with action and then with ideas. | |

|

Stage Five (12- |

Tertiary circular reactions (new means through active experimentation): experimentation and creativity in the actions of the “little scientist” Example: putting a teddy bear in the toilet and flushing it |

|

Stage Six (18- |

Mental representations (new means through mental combinations): considering before doing, which provides the child with new ways of achieving a goal without resorting to trial- Example: before flushing, remembering that the toilet overflowed and mother was angry the last time, and hesitating |

Stages One and Two: Simple Reflexes and Primary Circular ReactionsFor the first two stages, infants focus primarily on themselves. Stage one, called the stage of simple reflexes, includes the neonatal reflexes that infants use during their first month of life, the foundations of infant thought. During this stage, the newborn’s motor reflexes evoke certain brain reactions.

Soon sensation leads to perception, which ushers in stage two, first acquired adaptations or primary circular reactions (also called the stage of first habits). This stage lasts from one month to four months. It is a primary circular reaction because this is when infants begin to put together two separate actions or sensations, such as looking and touching or listening and touching, to form a habit. For example, the infant places her thumb in her mouth, finds it soothing, and begins to suck. Over time, the two separate actions become one combined action, repeated over and over (circular).

Newborns reflexively suck anything that touches their lips. By about 1 month, they have adapted this reflex to bottles or breasts, pacifiers or fingers, each requiring specific types of tongue-

118

Stages Three and Four: Secondary Circular Reactions and Coordination of Secondary Circular ReactionsIn stages three and four, reactions are no longer confined to the infant’s body; they are an interaction between the baby and something else in the external world. During stage three (4 to 8 months), infants attempt to produce exciting experiences, making interesting events last. Infants will continue to repeat those actions over and over because of their consequences. For example, realizing that rattles make noise, they wave their arms and laugh whenever someone puts a rattle in their hand. The sight of something delightful—

Next comes stage four (8 months to 1 year), coordination of secondary circular reactions or new adaptation and anticipation, also called the means to the end because babies have goals that they try to reach. At this stage, infants begin to show intentionality. Often they ask for help (fussing, pointing, gesturing) to accomplish what they want. Thinking is more innovative because adaptation is more complex. For instance, instead of always smiling at Daddy, an infant might first assess Daddy’s mood and then try to engage. Stage-

That initiation is goal-

119

Object PermanencePiaget thought that, at about 8 months, babies first understand object permanence—the concept that objects or people continue to exist when they are no longer in sight. As Piaget predicted, beginning at about 8 months, infants search for toys that have fallen from the crib, rolled under a couch, or disappeared under a blanket. Babies who are blind also acquire object permanence toward the end of their first year, reaching for an object that they hear nearby (Fazzi et al., 2011).

Piaget developed a basic experiment to measure object permanence: An adult shows an infant an interesting toy and then covers it with a lightweight cloth. The results are as follows:

- Infants younger than 8 months do not search for the object (by removing the cloth).

- At about 8 months, if infants are given the opportunity to search immediately (by removing the cloth), they do so; however, if they have to wait a few seconds before beginning to search, they forget that the object was there.

- By 2 years, children fully comprehend object permanence, progressing through several stages of ever-

advanced cognition (Piaget, 1954).

Piaget believed that an infant’s failure to search before 8 months of age was evidence that the baby had no concept of object permanence—

Piaget further tested this ability by conducting the following type of experiment. A research assistant (RA) shows an infant an attractive toy and places it under one of two cloths, cloth A. The infant looks, and reaches for the toy under cloth A. The RA places the toy under cloth A several more times, allowing the infant to reach for it each time. Then, the RA changes the hiding spot and places the toy under cloth B, right in front of the infant. Which cloth will the infant lift up? Cloth A. This is called A-not-B error.

Stages Five and Six: Tertiary Circular Reactions and Mental RepresentationIn their second year, infants start experimenting in thought and deed—

Stage five (12 to 18 months) is called tertiary circular reactions or new means through active experimentation, when goal-

ESPECIALLY FOR Parents of Toddlers One parent wants to put away all the breakable or dangerous objects because a toddler is now able to move around independently. The other parent says that the baby should learn not to touch certain things. Who is right?

Finally, in the sixth stage (ages 18 to 24 months), toddlers enter the stage of new means through mental combinations. Thankfully, stage-

120

Piaget also described deferred imitation, another stage-

who got into a terrible temper. He screamed as he tried to get out of a playpen and pushed it backward, stamping his feet. Jacqueline stood watching him in amazement, never having witnessed such a scene before. The next day, she herself screamed in her playpen and tried to move it, stamping her foot lightly several times in succession.

[Piaget, 1945/1962]

Piaget Re-

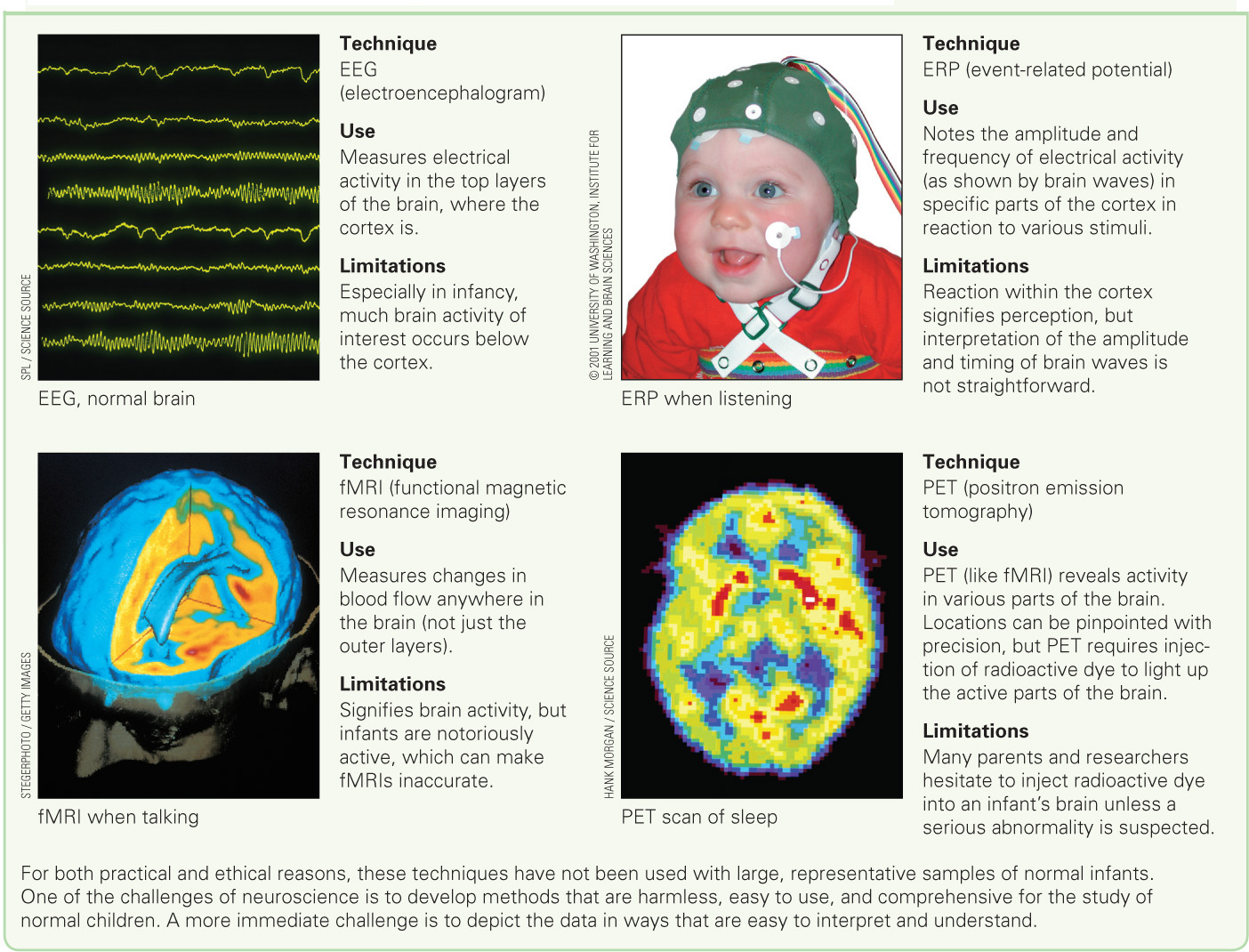

A major limitation of Piaget’s method for determining what infants could think is that it relied only on direct observation of behaviour, such as noticing whether or not a baby pulled away a cloth to search for a hidden object. Scientists now have many ways of measuring brain activity long before any observable evidence is apparent (see TABLE 3.4) (Johnson, 2010).

Some require millisecond video analysis, such as whether an infant stares at a disappearing object for 20 or 30 milliseconds. Before any conclusions are drawn, data from dozens of infants need to be analyzed statistically. Other techniques involve brain scans. For example, in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a burst of electrical activity measured by blood flow within the brain is recorded, indicating that neurons are firing. This leads researchers to conclude that a particular stimulus has been noticed and processed, even if the infant takes no action.

Brain scans are one way to investigate mirror neurons, an astonishing discovery that arose from careful research on monkeys—

For example, when one macaque saw another reach for a banana, the same brain areas were activated (lit up in brain scans) in both monkeys. Mirror neurons in the F5 area of the observing macaque’s premotor cortex responded to what was observed. Using increasingly advanced technology, neuroscientists have now found mirror neurons in several parts of the human brain (Keysers & Gazzola, 2010).

Many scientists are particularly interested in the implications for infant cognition. Perhaps the avid watching and listening that babies do enable them to learn long before Piaget realized. Because of mirror neurons, their understanding of objects, language, or human intentions might be far more advanced than researchers have demonstrated (Diamond & Amso, 2008; Rossi et al., 2011; Virji-

Scientists are now convinced that infants have memories, goals, deferred imitation, and mental combinations well in advance of the timing that Piaget proposed for his stages (Bauer et al., 2010; Morasch & Bell, 2009). Piaget was correct to describe babies as eager learners. He simply underestimated how rapidly that learning occurs.

121

Information Processing

Piaget’s four periods of cognition contrast with information-processing theory, a perspective originally modelled after computer functioning, including input, memory, programs, calculation, and output.

Information-

The information-

The term infant (or childhood) amnesia refers to the belief that adults and older children can remember almost nothing that took place before the age of 2 years. Information processing has revealed otherwise. We now focus on one specific aspect of the information-

122

MemoryEvidence for infant memory comes from innovative experiments in which 3-

Virtually all the infants began making some occasional kicks (as well as random arm movements and noises) and realized, after a while, that kicking made the mobile move. They then kicked more vigorously and frequently, sometimes laughing at their accomplishment. So far, this is no surprise—

When some infants had the mobile-

Then the lead researcher, Carolyn Rovee-

123

Other research finds that repeated reminders are more powerful than single reminders, and that context is crucial, especially for infants younger than 9 months old: Being tested with the same mobile in the same room as the initial experience aids memory (Rovee-

Scientists now believe that an infant’s memory begins to develop prenatally, when the baby is still in the womb. For example, one Canadian study used technologies such as ultrasound and image processing to measure a fetus’s heart rate while listening to its mother and a female stranger reading passages in English and Mandarin. The fetuses showed an increase in heart rate when they heard their mother’s voice and their native language, indicating they had developed memories of the voices and languages to which they were repeatedly exposed (Kisilevsky et al., 2009).

So, very young infants can remember, even if they cannot later put memories into words. Memories are particularly evident when

- experimental conditions are similar to those of real life

- motivation is high

- retrieval is strengthened by reminders and repetition.

The Active BrainThe crucial insight from information processing is that the brain is a very active organ, even in infancy, so that the particulars of experiences and memory are critically important in determining what a child knows or does not know. Soon generalization is possible. In another study, after 6-

124

Other research finds that toddlers transfer learning from one object or experience to another. They learn from many people and events—

Many studies show that infants remember not only specific events and objects, but also patterns and general goals (Keil, 2011). Some examples come from research, such as infants’ memory of syllables and rhythms that they have heard, or their understanding of how objects move in relation to others; additional examples arise from close observations of babies at home, such as their understanding of what they expect from Mommy as compared to Daddy, or what details indicate bedtime. Every day of their young lives, infants are processing information and storing conclusions.

KEY points

- Infants demonstrate cognitive advances throughout their first years.

- Piaget described cognition in the first two years as sensorimotor development, a period that has six stages, from reflexes to new exploration and deferred imitation.

- Piaget said that object permanence begins at 8 months, but more recent research finds that it starts earlier.

- Information-

processing theory traces the step- by- step learning of infants. Each advance is seen as the accumulation of many small advances, not as a new stage. - Very young infants can store memories, especially if they are given reminder sessions.