16.1 Death and Hope

A multicultural life-

|

Death occurs later. A century ago, the average life span worldwide was less than 40 years. Half of the world’s babies died before age 5. Now newborns are expected to live to age 79; in many nations, elderly people age 85 and over are the fastest- |

| Dying takes longer. In the early 1900s, death was usually fast and unstoppable; once the brain, the heart, or other vital organs failed, the rest of the body quickly followed. Now death can often be postponed through medical intervention: Hearts can beat for years after the brain stops functioning, respirators can replace lungs, and dialysis can do the work of failing kidneys. As a result, dying is often a lengthy process. |

| Death often occurs in hospitals. A hundred years ago, death almost always occurred at home, with the dying person surrounded by familiar faces. Now many deaths occur in hospitals, surrounded by medical personnel and technology. |

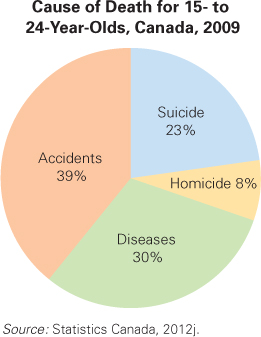

| The main causes of death have changed. People of all ages once died of infectious diseases (tuberculosis, typhoid, smallpox), and many women and infants died in childbirth. Now disease deaths before age 50 are rare, and almost all newborns (99 percent) and their mothers (99.99 percent) live, unless the infant is very frail or medical care of the mother is grossly inadequate. |

|

And after death… People once knew about life after death. Some believed in heaven and hell; others, in reincarnation; others, in the spirit world. Many prayers were repeated— |

| Source: Adapted from Kastenbaum, 2006. |

566

You will see that one emotion is constant: hope. It appears in many ways: hope for life after death, hope that the world is better because someone lived, hope that death occurred for a reason, hope that survivors rededicate themselves.

Cultures, Epochs, and Death

Few people in developed nations have actually witnessed someone die. This was not always the case. Those who reached age 50 in 1900 in North America and who had had 20 classmates in their high school class would have already seen at least six of their classmates die. The survivors would have visited and reassured several of their friends dying at home, promising to see them in heaven. Shared religious beliefs led almost everyone to believe in life after death.

Now fewer people die before old age, and those who do usually die suddenly and unexpectedly, most often in motor vehicle collisions. Ironically, death has become more feared as it has become less familiar (Carr, 2012). Accordingly, we begin by describing various responses to death, to help each of us find the hope that death can provide.

Ancient TimesOne of the signs of a “higher” animal is reacting with sorrow when death occurs. Elephants and chimpanzees have done that for hundreds of thousands of years. Jane Goodall reported that when the chimp Flo died, Flo’s older daughter was away, so Flo’s youngest son (Flint), alone, became “hollow-

Humans have developed ways to deal with their grief. Paleontologists believe that 100 000 years ago, the Neanderthals buried their dead with tools, bowls, or jewellery, signifying belief in an afterlife (Hayden, 2012). The date is controversial: Burial could have begun 200 000 years ago or only 20 000 years ago, but it is certain that by 5000 years ago death had become an occasion for hope, mourning, and remembrance. Two ancient Western civilizations with written records—

The ancient Egyptians built magnificent pyramids, refined the science of mummification, and scripted written instructions (called the Book of the Dead) to aid the soul (ka), personality (ba), and shadow (akh) in reuniting after death, blessing and protecting the living (Taylor, 2010). The fate of a dead Egyptian depended partly on his or her actions while alive, partly on the circumstances of death, and partly on proper burial by the family. That made death a reason to live morally and to honour the past. The Egyptians believed that if a dead person was not appropriately cared for after death, the living would suffer.

For the ancient Greeks, continuity between life and death was an evident theme, with hope for this world and the next. The fate of a dead person depended on past good or evil deeds. A few would have a blissful afterlife, a few were condemned to torture (in Hades, a form of hell), and most would exist in a shadow world until they were reincarnated to live another life.

567

Three themes are apparent in all the known ancient cultures, not only those of Greece and Egypt, but also in the Mayan, Chinese, and African cultures:

- Actions during life were thought to affect destiny after death.

- An afterlife was more than a hope; it was assumed.

- Mourners responded to death with specific prayers and offerings, in part to prevent the spirit of the dead person from haunting and hurting them.

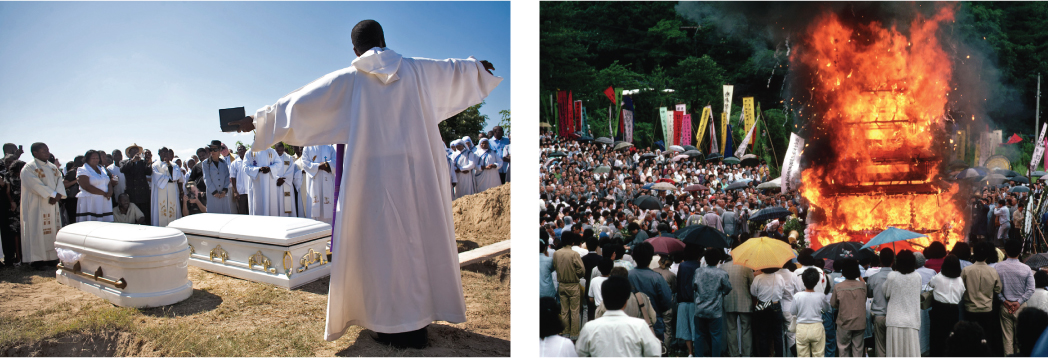

Contemporary Religion and DeathNow let us look at contemporary religions. Each faith seems distinct. As one review states, “Rituals in the world’s religions, especially those for the major tragic and significant events of bereavement and death, have a bewildering diversity” (Idler, 2006). Some details illustrate this diversity.

According to many branches of Hinduism, a person should die on the floor, surrounded by family, who neither eat nor wash until the funeral pyre is extinguished. By contrast, among some (but not all) Christians, mourners gather at a family member’s home or in a church, and share in the fellowship of food and drink, sometimes with music and dancing. In many Muslim and Hindu cultures, the dead person is bathed by the next of kin; among some Aboriginal peoples (e.g., the Navajo), no family member touches the dead person.

Although religions everywhere have specific beliefs and rituals, there is a great deal of diversity within each religion. For instance, some Buddhist rituals help believers accept a person’s death and detach from grieving in order to escape the suffering that living without the person entails. Other rituals help people connect to the dead, part of the continuity between life and death (Cuevas & Stone, 2011). Beliefs and rituals vary by region, too. There are more than 600 First Nations bands in Canada, each with its own heritage: It is a mistake to assume that all First Nations peoples have the same customs.

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What symbols do you notice in the photo that might help with grief?

The white coffin indicates that the infant was without sin and will therefore be in heaven, and the red roses are a symbol of love.

Religious practices change as historical conditions do. One specific example comes from Korea. Traditionally, Koreans were opposed to autopsies because the body is considered a sacred gift from the parents. However, contemporary Koreans recognize that medical schools need bodies to autopsy in order to teach science to the next generation. This clash led to a new custom: a special religious service honouring the dead who give their body for medical education ( J-

Diversity is also evident in descriptions of life after death. Some religions believe in reincarnation—

The Western practice of building a memorial, dedicating a plaque, or naming a location for a dead person is antithetical to Eastern cultures, in which all signs of the dead are removed after proper prayers have been said, in order to allow the spirit to leave in peace. This difference in customs was evident when terrorist bombs in Bali, Indonesia, killed 38 Indonesians and 164 foreigners, mostly Australian and British. The Indonesians prayed intensely and then destroyed all reminders; the Australians raised money to build a memorial (de Jonge, 2011). Neither group understood the deep emotions of the other.

568

There are variations in what happens to a dead body. An open casket and then burial is traditional among Christians in North America. Caskets themselves can be luxurious, silk-

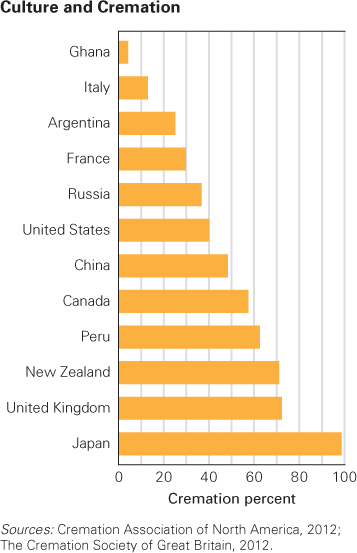

In most nations of Asia, from India in the west to Japan in the east, bodies are cremated and returned to the land or water, a practice that is becoming more common among other cultures, although regional variations exist (see Figure EP.1). Ashes may be interred next to buried coffins or may be scattered.

In some cultures, a home altar is created, where the living can commune with the spirits of the dead. Spirits not only hover in their special spot, but they also travel—

In recent decades, people everywhere have become less devout, a fact evident in surveys of religious beliefs as well as in attendance at religious services. And yet, people worldwide become more religious when confronted with their own or someone else’s death, seeking reassurances of hope in an afterlife in the face of loss and potential despair. This is true even for people who do not consider themselves religious (Heflick & Goldenberg, 2012).

Regardless of the diversity of death customs and beliefs, death has always inspired strong emotions, many of which can be constructive or life-

Understanding Death Throughout the Life Span

Thoughts about death are influenced by each person’s cognitive maturation and past experiences. Here are some of the specifics.

A Child’s Understanding of DeathSome adults think children are oblivious to death; others believe children understand death and should participate in funerals and other rituals, just as adults do (Talwar et al., 2011). You know from your study of childhood cognition that neither view is completely correct.

Children as young as 2 have some understanding of death, but their perspective differs from that of older people. One idea they find particularly incomprehensible is that the dead person or animal cannot come back to life; it takes a while for the reality of the situation to sink in. As a result, a child might not be sad initially when a person or animal dies but might later have moments of profound sorrow, when they realize that their loved one is not coming back.

569

In addition to sadness, a child who loses a friend, a relative, or a pet typically demonstrates loneliness, anger, and other signs of mourning, but adults cannot be certain how a particular child might react. For example, one 7-

That boy’s parents were taken aback by the depth of their son’s emotions. They regretted that they had not taken him to the animal hospital to say goodbye to the dog. The boy angrily refused to go back to school, saying, “I wanted to see him one more time.…You don’t understand.…I play with Twick every day” (quoted in K. R. Kaufman & Kaufman, 2006).

Because the loss of a particular companion is a young child’s prime concern, it is not helpful to say that a dog can be replaced. Even a 1-

If a child realizes that adults are afraid to say that death has occurred, the child might conclude that death is so horrible that adults cannot talk about it—

Remember how cognition changes with development. Egocentric preschoolers may fear that they, personally, caused death and may be seriously troubled that their unkind words or thoughts killed someone. As children become concrete operational thinkers, they seek specific facts, such as exactly how a person died and where he or she is now. Adolescents may be self-

At every age, questions should be answered honestly, in words the child can understand. In a study of 4-

If a child encounters death, adults should listen with full attention, neither ignoring the child’s concerns nor expecting adult-

Children who themselves are fatally ill typically fear that death means being abandoned by beloved and familiar people (Wolchik et al., 2008). Consequently, parents are advised to stay with a dying child day and night, holding, reading, singing, and sleeping, always ensuring that the child is not alone.

Understanding Death in Late Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood“Live fast, die young, and leave a good-

Terror management theory explains some illogical responses to death, including why young people take death-

570

As already noted, many studies have found that when health promotion messages explicitly link negative behaviours with death, it may ironically increase the likelihood of engaging in that behaviour (Goldenberg & Arndt, 2008); for example, it may increase smoking in teenagers and young adults who want to protect their pride and self-

Other research in many nations has found that when adolescents and emerging adults thought about death, they sometimes tried to hold onto their self-

Teenagers who themselves are dying of a fatal disease tend to be saddened and shocked (“Why me?”) at first, and then they try to live life to the fullest, proving that death cannot conquer them. One dying 17-

don’t be scared of death. Don’t go and lock yourself in your little room, under your little bedcovers, and just sit there and cry and cry and cry. Don’t do that because you’re wasting time, and you’re not only hurting yourself, you’re hurting the people around you.…That’s why never ever ever stop doing what you love. Just be yourself. Be normal. Don’t shut them out, but bring them in—

[Kellehear & Ritchie, 2003]

Understanding Death in AdulthoodA shift in attitudes toward death occurs when adults become responsible for work and family. Death is no longer romanticized; it is to be avoided or at least postponed. Fear of death builds in early adulthood, reaching a lifetime peak in middle age.

Many adults stop taking addictive drugs, start wearing seat belts, and adopt other precautions when they become parents. One of my students eagerly anticipated the thrill of her first skydive. She reserved her spot on the plane and paid in advance. However, the day before the scheduled dive she learned she was pregnant. She forfeited the money and shopped for prenatal vitamins instead.

When adults hear about another’s death, their reaction is closely connected to the person’s age. Death in the prime of life is harder to accept than death in late adulthood.

To defend themselves against the fear of aging and untimely death, adults often ask for details about a person’s death to convince themselves that their situation is different. Sometimes the deceased was much older and had been ailing; in that case, adults do not take the death personally. If the dead person was a contemporary or even younger, then adults seek to explain why that person’s genes, or habits, or foolish behaviour is unlike their own.

In other situations, adults may not readily accept the death of others—

Nor do adults readily accept their own death. A woman diagnosed at age 42 with a rare and almost always fatal cancer (a sarcoma) wrote:

571

I hate stories about people dying of cancer, no matter how graceful, noble, or beautiful.…I refuse to accept that I am dying; I prefer denial, anger, even desperation.…I resist the lure of dignity; I refuse to be graceful, beautiful, beloved.

[Robson, 2010, 28]

Reactions to one’s own mortality differ depending on developmental stage as well. In adulthood, from ages 25 to 65, terminally ill people worry about leaving something undone or abandoning family members, especially children.

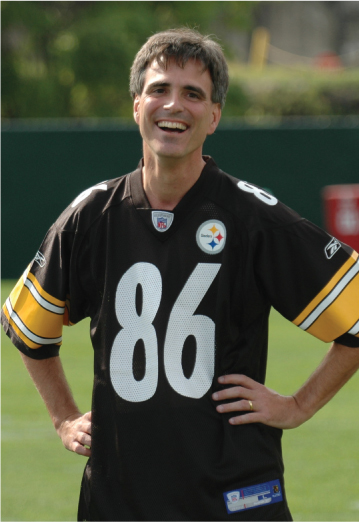

One such adult was Randy Pausch, a 47-

Attitudes about death are often irrational. Rationally, adults should work to change social factors that increase the risk of mortality—

Death in Late AdulthoodIn late adulthood, attitudes about death shift again. Anxiety decreases; hope rises (De Raedt et al., 2013). Life-

This shift in attitudes is beneficial. Indeed, many developmentalists believe that one sign of mental health among older adults is acceptance of mortality and an increasing altruistic concern about those who will live on after them. As a result, older people write their wills, designate health care proxies, read scriptures, reconcile with estranged family members, and, in general, tie up all the loose ends that most young adults avoid (Kastenbaum, 2012). Sometimes middle-

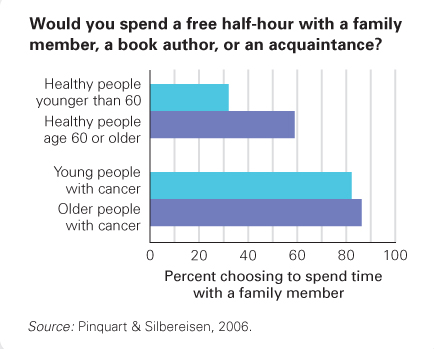

Acceptance of death does not mean that the elderly give up on living. On the contrary, most try to maintain their health and independence. However, priorities shift. In an intriguing series of studies (Carstensen, 2011), people were presented with the following scenario:

572

© NATHAN BENN/CORBIS

Imagine that in carrying out the activities of everyday life, you find that you have half an hour of free time, with no pressing commitments. You have decided that you’d like to spend this time with another person. Assuming that the following three persons are available to you, with whom would you want to spend that time:

- a member of your immediate family

- the author of a book you have just read

- an acquaintance with whom you seem to have much in common?

Older adults, more than younger ones, choose the family member. The researchers explain that family becomes more important when death seems near. This is supported by a study of 329 people of various ages who had recently been diagnosed with cancer and a matched group of 170 people (of the same ages) who had no serious illness (Pinquart & Silbereisen, 2006). The most marked difference was between those with and without cancer, regardless of age (see Figure EP.3). Life-

Near-Death Experiences

Even coming close to death is often an occasion for hope. This is most obvious in what is called a near-

I was in a coma for approximately a week.…I felt as though I were lifted right up, just as though I didn’t have a physical body at all. A brilliant white light appeared.…The most wonderful feelings came over me—

[quoted in R. A. Moody, 1975]

Near-

573

Nevertheless, a reviewer of near-

KEY points

- Since the mid-

twentieth century, first- hand experience with death has become less common and therefore death less familiar. In the nineteenth century, everyone knew several people who died before age 40. - Ancient cultures and current world religions have various customs about death, which help people live better lives as they respond to sorrow with hope.

- People react to death differently, depending on their developmental stage, with older adults less anxious than younger ones.

- Near-

death experiences seem to make people more spiritual, less materialistic, and more appreciative of others.