Growing Older

“Aging, we are all doing it,” a subway poster proclaims. That poster is designed to make us think. Although we are all aging, few of us realize it because organ reserve and homeostasis (described in Chapter 11) allow declines to be unnoticed at least until middle adulthood and perhaps later.

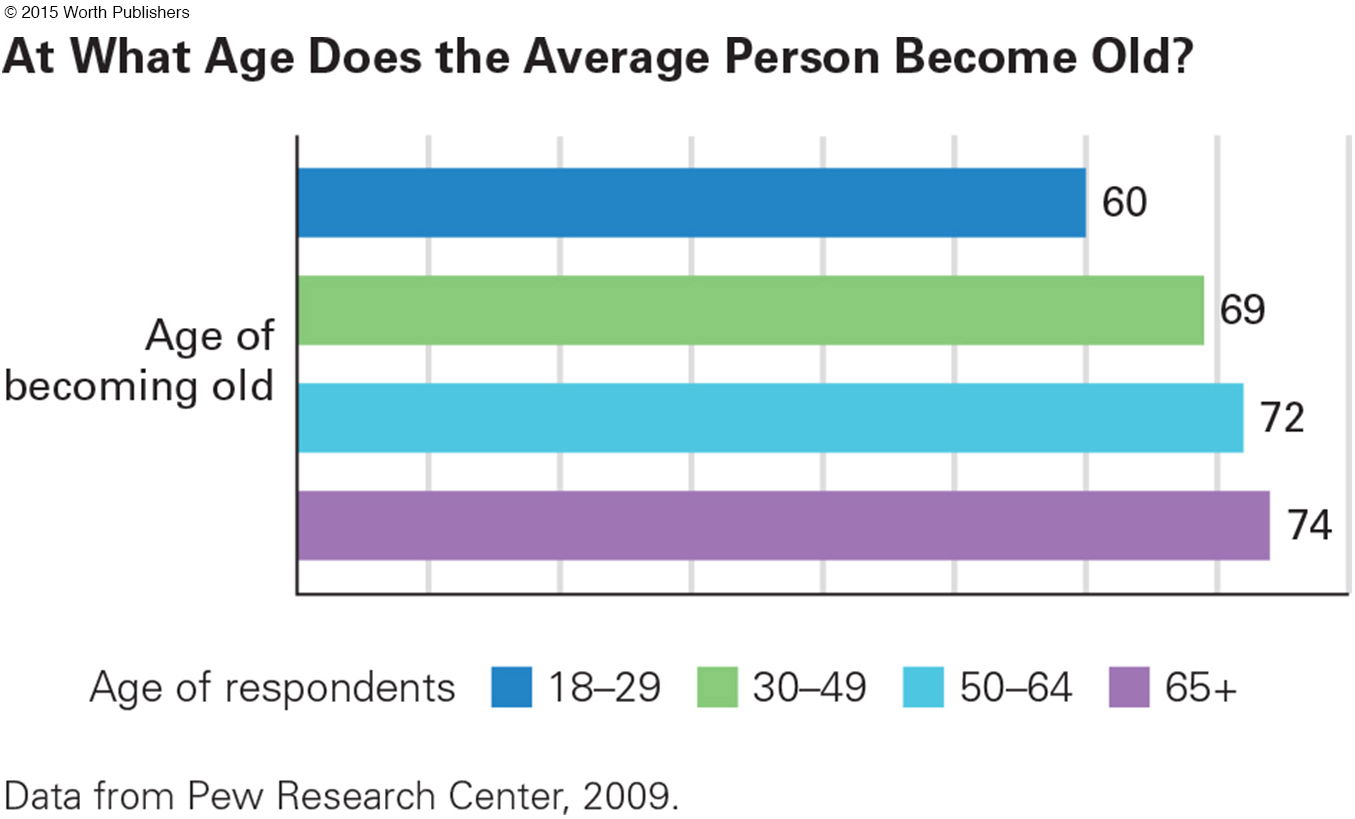

Typically, 30-

Most adults consider themselves strong, capable, and healthy. Economic analysis supports this perception: Adults ages 26 to 60 contribute more to the society than those older or younger, adding a surplus to aid those not yet, or no longer, “in their prime” (Zagheni et al., 2015).

Allostatic load, also described in Chapter 11, builds quickly or slowly, so some people at the end of this stage (age 65) seem decrepit while others seem youthful. Measured by 18 indicators of health and aging—

429

senescence

The process of aging, whereby the body becomes less strong and efficient.

Genes are important, too, of course. Senescence, as the aging process is called, is genetically coded for every species. Our human genes cause us to live much longer than dogs but not as long as some tortoises.

However, within each species, the environment (both personal choices and the social context) is the main reason one individual lives twice as long and with more vitality than another. Variation in aging among humans, currently and over the centuries, is vast, but this is not primarily because of genes (Robert & Labat-

Exercise

Adults do not move their legs, arms, or even hands as much as adults did a century ago, thanks to many modern devices, from the automobile to the TV remote. Fortunately, adults are becoming increasingly aware of the need to be active. More (51 percent) meet the U.S. weekly goal of 150 minutes of moderate exercise or 75 minutes of intense exercise than adults did 15 years ago (41 percent) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2014).

Regular physical activity protects against serious illness even if a person smokes, drinks, or overeats (all discussed soon). Exercise reduces blood pressure, strengthens the heart and lungs, and makes depression, osteoporosis, heart disease, arthritis, and some cancers less likely. Health benefits from exercise are substantial for men and women, old and young, former sports stars and those who never joined a team (Aldwin & Gilmer, 2013).

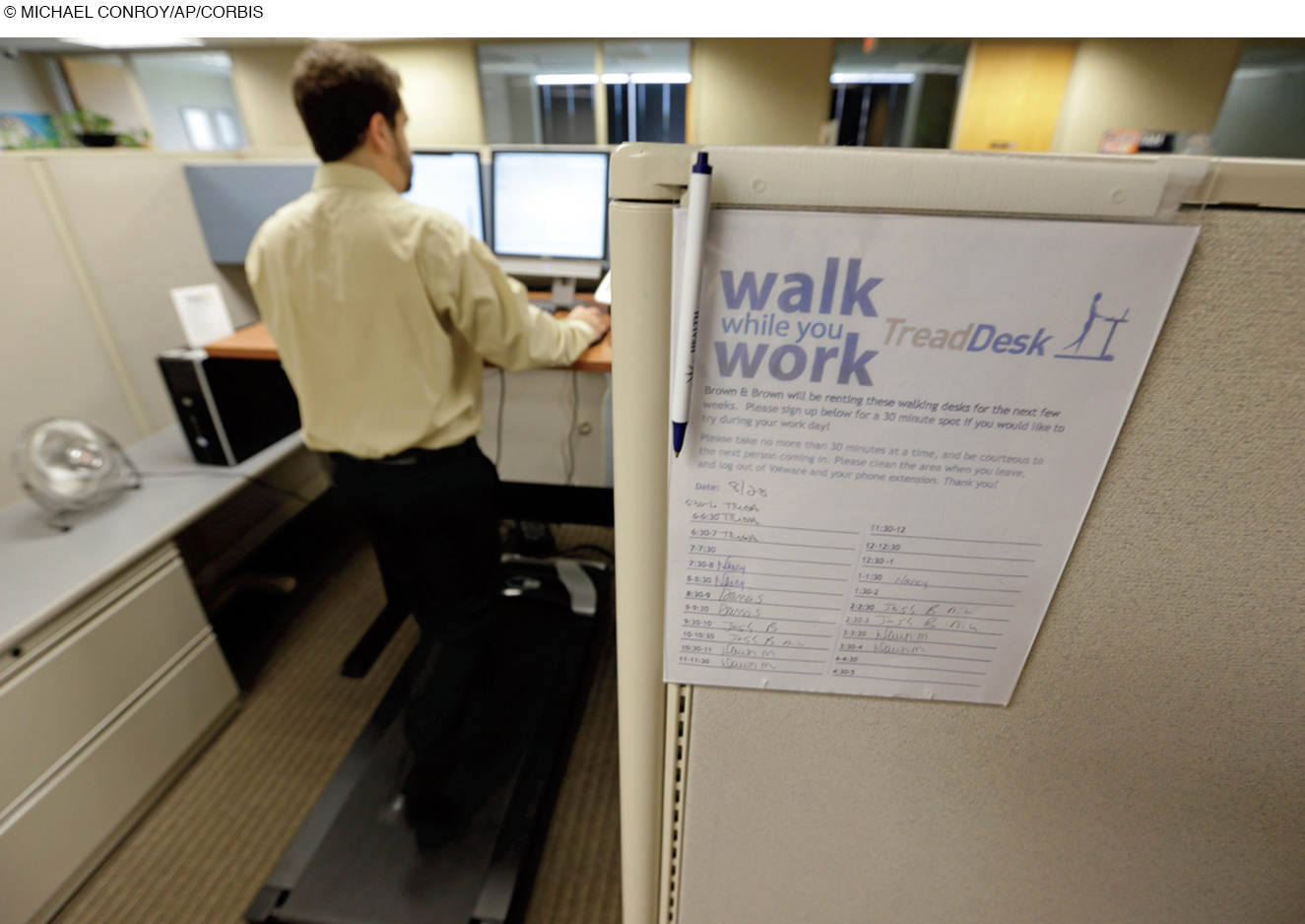

By contrast, sitting for long hours correlates with almost every unhealthy condition, especially heart disease and diabetes, both bringing additional health hazards beyond the disease itself. Even a little movement—

The close connection between exercise and physical and mental health is well known, as is the influence of family, friends, and communities on movement. Neighborhoods high in walkability (paths, sidewalks, etc.) reduce time driving and watching television (Kozo et al., 2012). This relationship between the surroundings, exercise, and health is causal, not merely correlational, because exercise strengthens the immune system (Davison et al., 2014). Moreover, active people feel energetic, which increases other good habits.

Drug Use

Drugs can be beneficial or harmful at every age. In adulthood, ideally, adults learn to use needed drugs, at the right dose, and avoid the others.

MEDICATION In the past month, in the United States, more than a third (39 percent) of 25-

430

Over the past 50 years, prescription medication has cut the adult death rate in half and markedly reduced disability. Childhood diabetes (type 1), for instance, was once a death sentence; now diet and insulin allow diabetics to reach the highest levels of success, as Supreme Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor did (Sotomayor, 2014). She began injecting herself at age 7; now she takes newer, less uncertain medication every day.

There is no accurate tally of over-

Research on coffee finds that adults make choices regarding that drug, too. The effect of coffee varies genetically, so some adults learn to avoid it and others to drink several cups a day (Cornelis et al., 2015). For some, coffee reduces various problems, including Type 2 diabetes (Palatini, 2015). For others, it disrupts nighttime sleep and undercuts daytime efficiency. Adults adjust accordingly.

ILLEGAL DRUGS Lessons learned from experimentation are also apparent with recreational drugs. As described in Chapter 11, abuse of illegal drugs decreases markedly over adulthood—

Unfortunately, abuse of prescribed medication is increasing. One reason is that such drugs are first given by a doctor to reduce pain, insomnia, or psychological distress. That makes it harder for adults to recognize the early signs of addiction, and thus some seek more prescriptions rather than trying to quit. Danger ahead.

THINK CRITICALLY: How would you apportion blame for drug addiction?

For example, after the trial of a man (age 33) who killed four people to get pills for himself and his addicted wife (age 30), the local attorney general said, “the genesis of the current prescription pill and heroin epidemic lies squarely at the feet of the medical establishment,” (Spota quoted in James, 2012). Of course, doctors feel unjustly accused for illegal prescription use. Addiction of all kinds raises the question as to who is to blame—

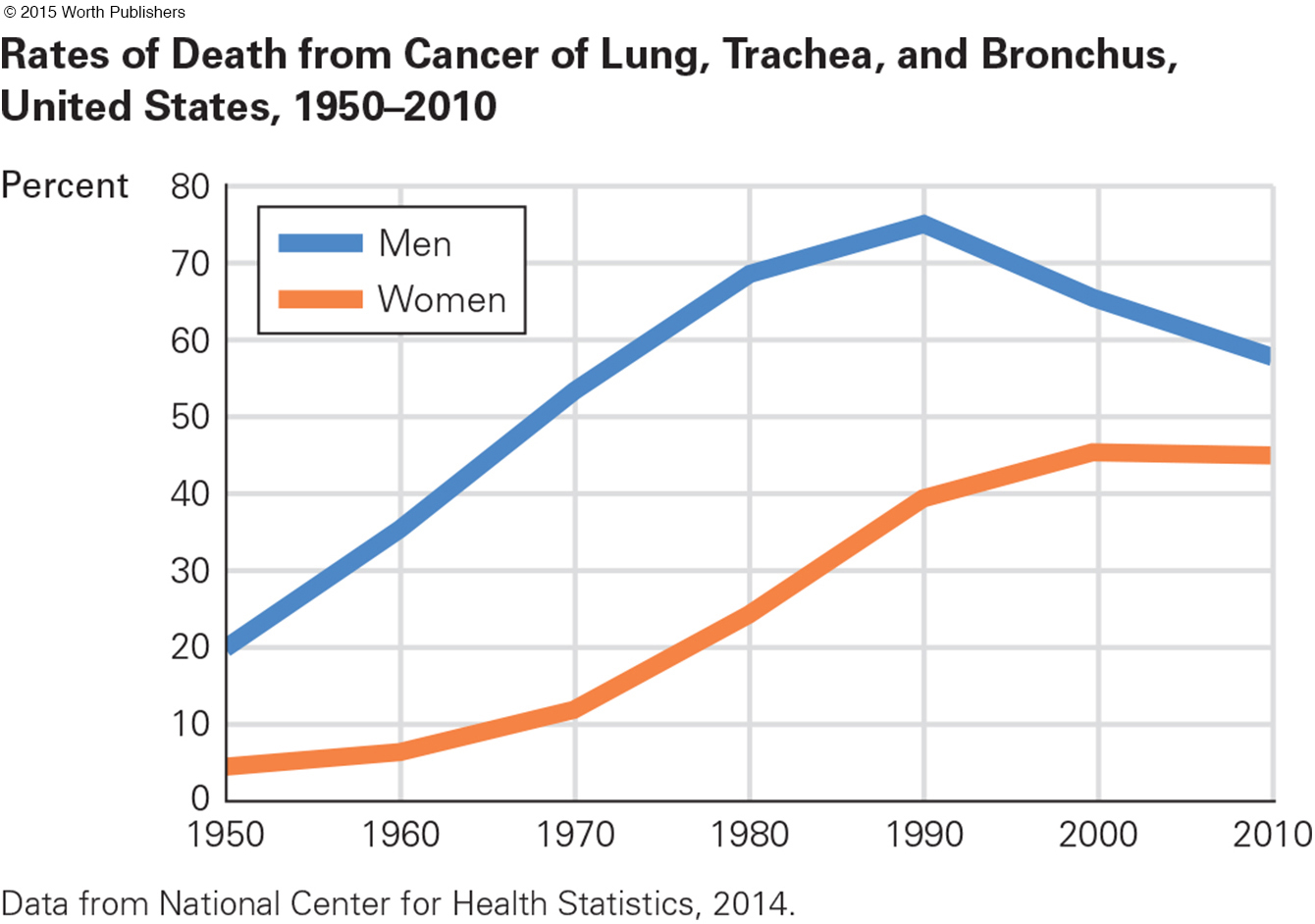

TOBACCO Society is pivotal for the drug that causes more deaths than any other, tobacco. About 70 percent of the lung cancer deaths worldwide, and 90 percent in industrialized nations, are caused by cigarettes (Ezzati & Riboli, 2012). Many other diseases are traced to tobacco as well.

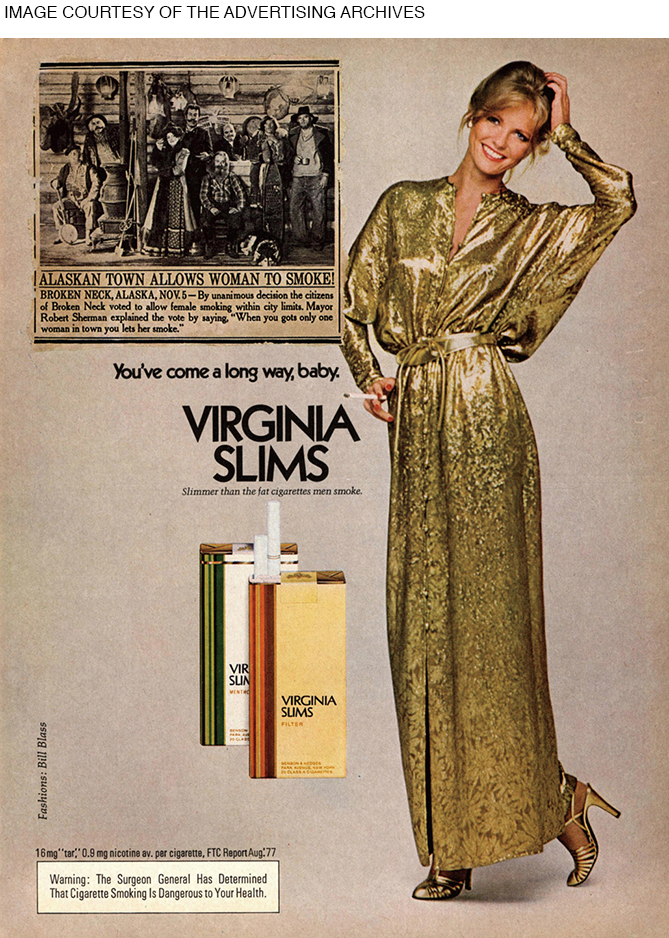

Cigarette smoking is a classic example of cohort effects. During World War II (1941–

Meanwhile, some women celebrated another historical happening, women’s liberation, by smoking—

431

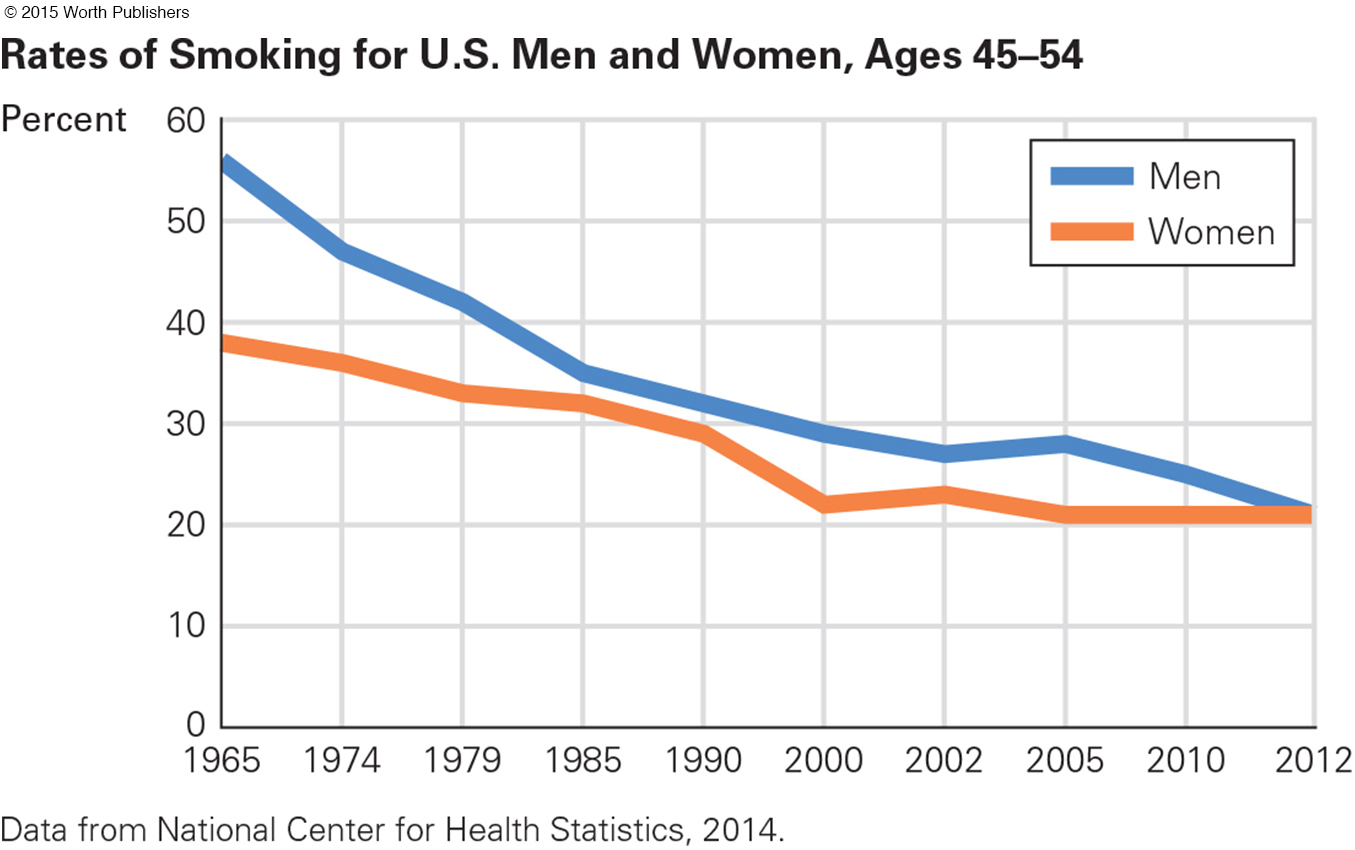

In the 1960s, more than half of U.S. adult men and more than a third of women smoked. By 2012, data showed that both sexes had decreased smoking but that fewer women had quit (see Figure 12.2).

Overall, 22 percent of adult men (age 25–

A half-

Not only cohort but also culture has a strong effect on both smoking and gender differences. Almost half the adults of both sexes in Germany, Denmark, Poland, Holland, Switzerland, and Spain smoke. A joke in Europe is “if you want to stop smoking, go to America.”

In poor nations, rates of smoking as well as lung cancer increase with income, because it costs money to buy cigarettes. Traditionally in Asia, women rarely smoked, but their rates are increasing rapidly (Lortet-

The World Health Organization calls tobacco “the single largest preventable cause of death and chronic disease in the world today,” with one billion smoking-

ALCOHOL The harm from cigarettes is dose-

432

In fact, some research reports that alcohol can be beneficial: Adults who drink wine, beer, or spirits in moderation—never more than two drinks a day—

Alcohol use disorder destroys brain cells, is a major cause of liver damage and several cancers, contributes to osteoporosis, decreases fertility, and accompanies many suicides, homicides, and accidents—

Alcohol abuse shows age, gender, cohort, and cultural differences. For example, the risk of accidental death while drunk is most common among young men: Law enforcement has cut their drunk-

In general, low-

Diet

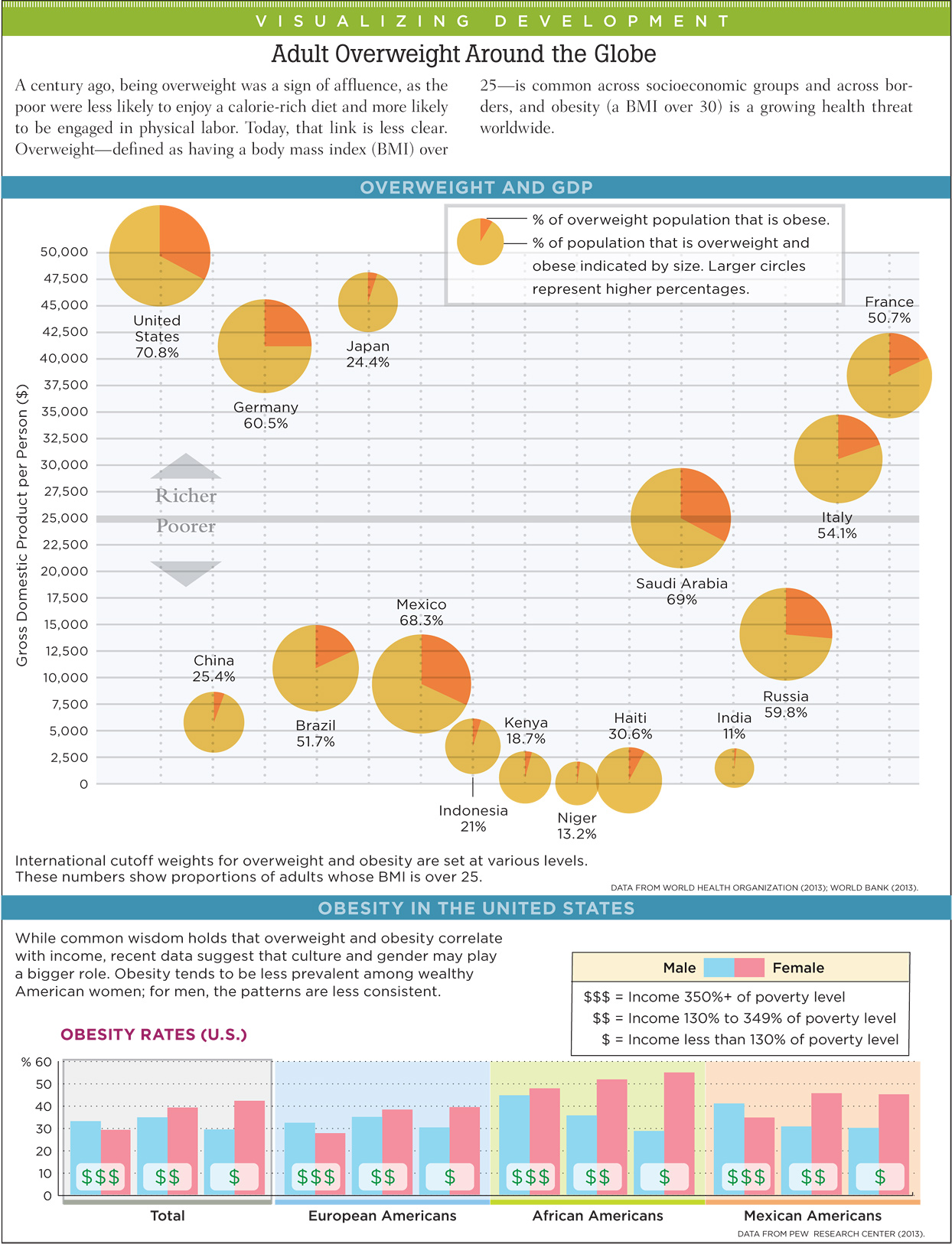

Weight trends are the opposite of alcohol use disorder. Internationally, overweight increases as nations become richer, and over the years of adulthood, obesity increases.

Obesity increases the risk of almost every disease. Consider just one example. Type 2 (adult onset) diabetes is increasing worldwide, causing eye, heart, and foot problems as well as early death. Genes for diabetes are often activated by body fat. Nature and nurture again.

NATIONS COMPARED In the United States, adults gain an average of one to two pounds each year. The biological reason is that between ages 20 and 60 metabolism decreases by one-

Over 40 years of adulthood, that adds 40 to 80 pounds. As a result, more than two-

433

Rates are lower elsewhere, but worldwide half a billion adults are obese. Obesity rates have plateaued in the United States but are accelerating in many other nations, particularly in Africa and Asia, where past malnutrition taught adults to eat whenever food was available. Worldwide, malnutrition was once the main nutritional problem; now obesity is (World Health Organization, 2013).

National context is crucial. In a surprising example, an economic crisis in Cuba from 1991 to 1995 meant less meat and more walking. Weight loss averaged 14 pounds, and rates of diabetes and heart disease fell. When the crisis was over, people regained weight and diabetes rates doubled (Franco et al., 2013). No wonder the United States is the world leader in obesity and diabetes, with other nations catching up.

Even diseases that are not caused by overweight will increase because the stigma endured by obese adults leads them to avoid doctors and nurses, to eat more, and to exercise less—

THINK CRITICALLY: Why did it take an economic crisis for the Cubans to lose weight?

Stigma may explain surprising sex differences: More U.S. women than men are at a healthy weight (do they care more?) or obese (do they give up if they can’t stay thin?). The 2012 numbers for adults (age 20–

ACHIEVING A HEALTHY WEIGHT The basics of a healthy diet are similar all over the world. Common in Greece and Italy is the so-

One surprising food has recently been proven to reduce obesity and mortality in all ethnic groups—

434

For morbidly obese adults, surgery may be the best option. About 200,000 U.S. residents undergo bariatric surgery each year. The rate of complications is high: About 1 percent die soon after the surgery and about 10 percent need a second operation.

THINK CRITICALLY: Why might survivors of bariatric surgery live longer than the average person?

Over time, however, surgery that successfully reduces overeating saves lives because morbid obesity increases the death rate (Adams et al., 2012). The greatest benefits seem to occur for people with diabetes: 70 percent find that their diabetes disappears, usually not to return (Arterburn et al., 2013). Indeed, bariatric surgery over the long term may improve health of the obese even compared to the general population—

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

A Habit Is Hard to Break

In this feature, unlike the others, the opposites are within each person: human emotions opposed to human knowledge. In this tug-

Everyone knows that cigarette smoking, alcohol abuse, overeating, and sedentary behavior are harmful, yet almost everyone has at least one destructive habit. Why don’t we all shape up and live right?

Breaking New Year’s resolutions; criticizing those whose habits are not ours; feeling guilty for consuming sugar, salt, fried foods, cigarettes, or alcohol; buying gym memberships that go unused or exercise equipment that becomes a coat rack or dust-

Many social scientists have focused on this disconnect between knowledge and action. One insight, inspired in part by social learning theory, is that changing a habit is a long, multistep process, sometimes conceptualized as five “stages of change” (Norcross et al., 2011; Gökbayrak et al., 2015). Tactics that work at one step fail at another. One list of these steps is: (1) denial, (2) awareness, (3) planning, (4) implementation, and (5) maintenance.

1. Denial occurs because all bad habits begin and continue for a reason. That makes denial a reasonable act of self-

For example, many adult smokers began as teenagers, using cigarettes to achieve important goals: to be socially accepted, to appear mature, and/or to control weight. Before they realized it, they were addicted. Soon, lack of nicotine made them anxious, confused, angry, and depressed. Smokers want relief, and denial helps them get it.

With many addictions, hearing how bad it is triggers anger, anxiety, defiance. That leads to more smoking, drinking, or so on (Maxfield et al., 2014; Ben-

Denial may prevent others from criticizing a habit. For instance, one out of eight smokers lies to his or her doctor about smoking. Younger adults are especially likely to lie (Curry et al., 2013). Obese people cannot lie about being overweight; instead they avoid doctors and strangers, eating alone to stop their anxiety. Denial protects against stress; people hide bottles, or wear baggy clothes, or whatever, to avoid confrontation.

2. Awareness is attained by the person him-

If someone else tries to encourage awareness by stating facts (e.g., telling a smoker about lung cancer), that can create a backlash. However, motivational interviewing may help.

In that interview, the individual is asked about the costs and benefits of the habit. Often people fluctuate between denial and dawning awareness; a good listener tips the balance by affirming what is said about the downside of the habit and stressing the person’s power of choice (Magill et al., 2014). However, motivational interviewing must be carefully done, lest denial rather than awareness is encouraged.

Self-

3. Planning is best when it is specific, such as setting a date for quitting and putting strategies in place to overcome the obstacles. A series of studies has found that humans tend to underestimate the power of their own impulses, which arise from brain patterns, not logic (Belin et al., 2013). Thus plans must include strategies to defend against momentary wavering. Overconfidence makes it difficult to break a habit.

In one study, researchers gave students who were entering or leaving a college cafeteria a choice of packaged snacks, promising them about $10 (and the snack) if they did not eat it for a week. Students entering the cafeteria, presumably aware of the demands of hunger, planned to avoid temptation by choosing a less desirable snack. Most (61 percent) earned the money. However, many of those who had just eaten chose a more desirable snack. Few (39 percent) earned the money because most ate the food before the week was up (Nordgren et al., 2009).

435

4. Implementation is changing the habit according to the plan. One crucial factor is social support, such as (1) letting others know the date and details of the plan, enlisting their help, (2) finding a buddy, or (3) joining a group (Weight Watchers, Alcoholics Anonymous, or another 12-

Implementation must reflect the values, circumstances, and supports of the individual. For instance, prayer was an effective part of implementation to improve diet and exercise of older Mexican American women (Schwingel et al., 2015). That would not help everyone.

Past successes increase self-

5. Maintenance is the most difficult step. Although quitting any entrenched habit is painful, many addicts have quit several times, recovered, and then relapsed. Dieters go on and off diets so often that this pattern has a name—

Willpower may be like a muscle, slowly gaining strength with activity but subject to muscle fatigue if overused -(Baumeister & Tierney, 2012). A man who has stopped abusing alcohol might party with friends who drink, confident that he will stick to juice; a dieter serves dessert to the rest of her family, certain that she’ll be able to resist a taste herself; someone who joined the gym will skip a day, planning to do twice as much tomorrow.

Such actions are dangerous. The dieter who skips the dessert uses so much willpower that she is defenseless at midnight, when leftover cake beckons. Maintenance fades when faced with stress. Many people who restart a bad habit explain that they did so because of a divorce, a new job, a rebellious teenager, or so on.

Of course, sooner or later every adult experiences a stressor; that is why maintenance strategies are crucial. When stress combines with opportunity, people mistakenly think that one cigarette, one drink, one slice of cake, one skipped day of exercise, and so on, is inconsequential—

Unfortunately, the human mind is geared toward all or nothing; neurons switch on or off, not halfway. For that reason, one puff makes the next one more likely, one potato chip awakens the urge for another, and so on. With alcohol, the drink itself scrambles the mind; people are less aware of their cognitive lapses under the influence and thus drink more after that first drink (Sayette et al., 2009).

Maintenance depends a great deal on the ecological context, which makes other people and circumstances crucial. A glass of wine poured when the former drinker wasn’t looking, rain that makes jogging difficult, a calorie-

Once a person is aware of a destructive habit (step two), it is not hard to plan and implement an improvement (steps three and four). But sticking to it (step five) is difficult if the context includes an unanticipated push in the opposite direction. Think again about the relationship between national culture and cigarette smoking: Almost all adult smokers want to quit, but whether they do depends on much more than their private wishes.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 12.1

1. What diseases and conditions are less likely in people who exercise every day?

People who exercise are more likely to have lower blood pressure, stronger hearts and lungs, and a reduced risk for the development of almost every disease, including depression, diabetes, osteoporosis, heart disease, arthritis, and cancer.

Question 12.2

2. What changes have occurred in adult exercise habits over recent decades?

Adults do not move their legs, arms, or even hands as much as adults did a century ago, thanks to modern technology such as the automobile and the TV. Fortunately, adults are becoming increasingly aware of the need to be active. More (51 percent) meet the U.S. weekly goal of 150 minutes of moderate exercise or 75 minutes of intense exercise than adults did 15 years ago.

Question 12.3

3. Why does abuse of prescription drugs increase in adulthood?

One reason is that such drugs are first given by a doctor to reduce pain, insomnia, or psychological distress. That makes it harder for adults to recognize the early signs of addiction, and thus some seek more prescriptions rather than trying to quit.

Question 12.4

4. What are the trends in cigarette smoking in North America?

In the United States, men have been quitting smoking for decades, which has decreased male lung cancer deaths. While men were quitting smoking, however, the number of women who smoke increased, which has increased female lung cancer rates. Fortunately, cigarette smoking has been declining over the past decade in North America for every gender and age group. In 1970, one-

Question 12.5

5. What gender differences are apparent in rates of cigarette smoking?

Recent data has shown that both sexes have decreased smoking but that fewer women have quit. Fifty years ago, five times as many U.S. men as women died of lung cancer. But because of cohort changes in when men and women started smoking, lung cancer now kills as many women as men.

Question 12.6

6. How does the relationship between dose and health differ for tobacco and alcohol?

Every bit of exposure to cigarette smoke makes cancer, heart disease, strokes, and emphysema more likely. No such linear harm results from drinking alcohol; in fact, some research reports that alcohol in moderation can be beneficial. Excessive drinking is always harmful, however.

Question 12.7

7. Who is most likely to be harmed by alcohol abuse?

The risk of accidental death while drunk is most common among young men; law enforcement has cut their drunk-

Question 12.8

8. What factors (food-

Too much meat, fat, and sugar and too little fiber are the main dietary culprits in the rate of obesity. Inadequate physical activity also affects the rate of obesity. Less than 50 percent of U.S. adults report that they engage in at least 20 minutes of daily exercise, and one study that used an objective assessment of adult movement found that fewer than 5 percent of U.S. adults get even 30 minutes per day of exercise.

Question 12.9

9. What are the consequences of obesity, in the United States and elsewhere?

Obesity increases the risk of almost every disease. Type 2 diabetes is just one example. Because genes for diabetes are often activated by body fat, it is increasing worldwide, causing eye, heart, and foot problems as well as early death.

Question 12.10

10. What are the benefits of the Mediterranean diet?

The Mediterranean diet, which is high in fiber and healthy fats, protects against heart disease without adding weight.

Question 12.11

11. Who is most likely to benefit from or be harmed by surgery to reduce obesity?

While the rate of complications is high for surgery, the greatest benefits seem to occur for people with diabetes: 70 percent find that their diabetes disappears, usually not to return.

436