Losses and Gains

437

The message that senescence is largely under personal and social control is comforting, but we must recognize that some effects of aging are inevitable. Bodies and minds are not the same at 65 as they were at 25. Always remember, however, that every period of life is multi-

Appearance

One of the obvious changes is appearance. Adults look older every decade.

SKIN AND HAIR The first visible signs of aging are in the skin, which becomes dryer and rougher. Collagen, the main component of the connective tissue of the body, decreases by about 1 percent per year, starting at age 20. By age 30, wrinkles become visible, particularly around the eyes. Diet has an effect—

Especially on the face (most exposed to sun, rain, heat, cold, and pollution), skin becomes less firm. By middle adulthood, age spots, tiny blood vessels, and other imperfections are visible in people who work outside (usually men), and troubling to people (usually women) who associate youth with sexual attractiveness.

Hair becomes gray and thin, first at the temples by age 40 and then over the rest of the scalp. Many men experience “male pattern baldness.” Appearance changes do not affect health, but they signify age, so adults spend money and time coloring, thickening, and styling.

SHAPE AND AGILITY The body changes shape between ages 25 and 65. A “middle-

By late middle age, adults are shorter, because back muscles, connective tissue, and bones lose density, making the vertebrae shrink. People lose about an inch (2 to 3 centimeters) by age 65. The loss is in the spine, not the leg bones, another reason that waists widen.

Muscles atrophy; joints lose flexibility; stiffness appears; bending is harder; balance more difficult. Rising from sitting, twisting in a dance, hoping on one foot, or even walking “with a spring in your step” is not as easy. A strained back, neck, or other body part may occur.

438

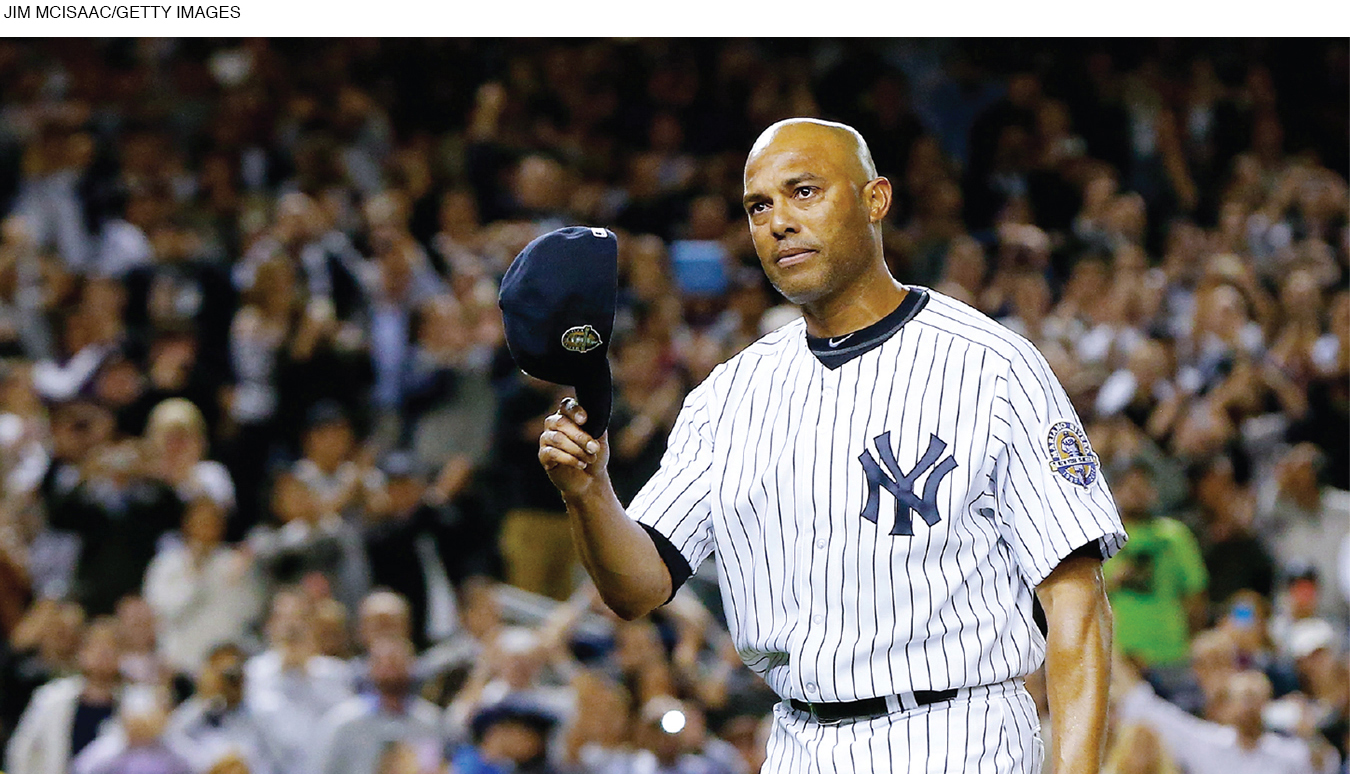

The aging of the body is most evident in sports that require strength, agility, and speed: Gymnasts, boxers, and basketball players are among the athletes who benefit from youth but who experience slowdowns by age 20.

THINK CRITICALLY: Is the saying “beauty is only skin deep” accurate?

These physiological changes seem clearly to be losses, but remember that adulthood may bring intellectual and emotional gains. In fact, some 30-

Disease in Adulthood

From childhood on, each person’s routines and habits powerfully affect every disease and chronic condition. This is particularly true for problems associated with aging—

Cancer (by far the most common cause of adult death before age 65) is a classic example. Most cancers are affected by the health habits just described that increase allostatic load. Pollution and neighborhood stress add to the problem. Genes are important as well—

ATTITUDE AND DISEASE Adults can stop abusing drugs, improve nutrition, and exercise regularly. They can decide to be screened and treated, or not. These actions postpone many diseases, and older adults are more likely to do them (Reyna et al., 2015).

Surprisingly, cancer survivors (estimated at 14.5 million people in the United States) are likely to become healthier after their illness. In the first year after treatment ends, many fear cancer’s return, experience less vitality or memory, and are depressed by reduced support. But then millions live decades after diagnosis, and “self-

Although aging brings infirmities, injuries, and diseases, that may have a bright side. A popular 2013 song repeated the folk saying “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” The hope is that each challenge that is overcome increases a trait called hardiness, an attitude that promotes learning from stress (Maddi, 2013).

Let us not be too sanguine. Stresses accumulate, and coping is not easy, as explained later in this chapter. Each illness makes another more likely, and chronic disease burdens adults with daily hassles. Many researchers believe that it is neither helpful nor proven to imply that attitude is a major cause of disease or recovery (Green McDonald et al., 2015).

Finding the right balance between hope and despair in explaining the connections between disease and attitude is not simple. Nonetheless, all the researchers agree that rates of disease and opportunities for growth both increase in adulthood.

SES, IMMIGRATION, AND HEALTH Money, education, and intelligence protect health. This is true among nations when only overall health is tallied, as well as when the focus is on each specific disease.

439

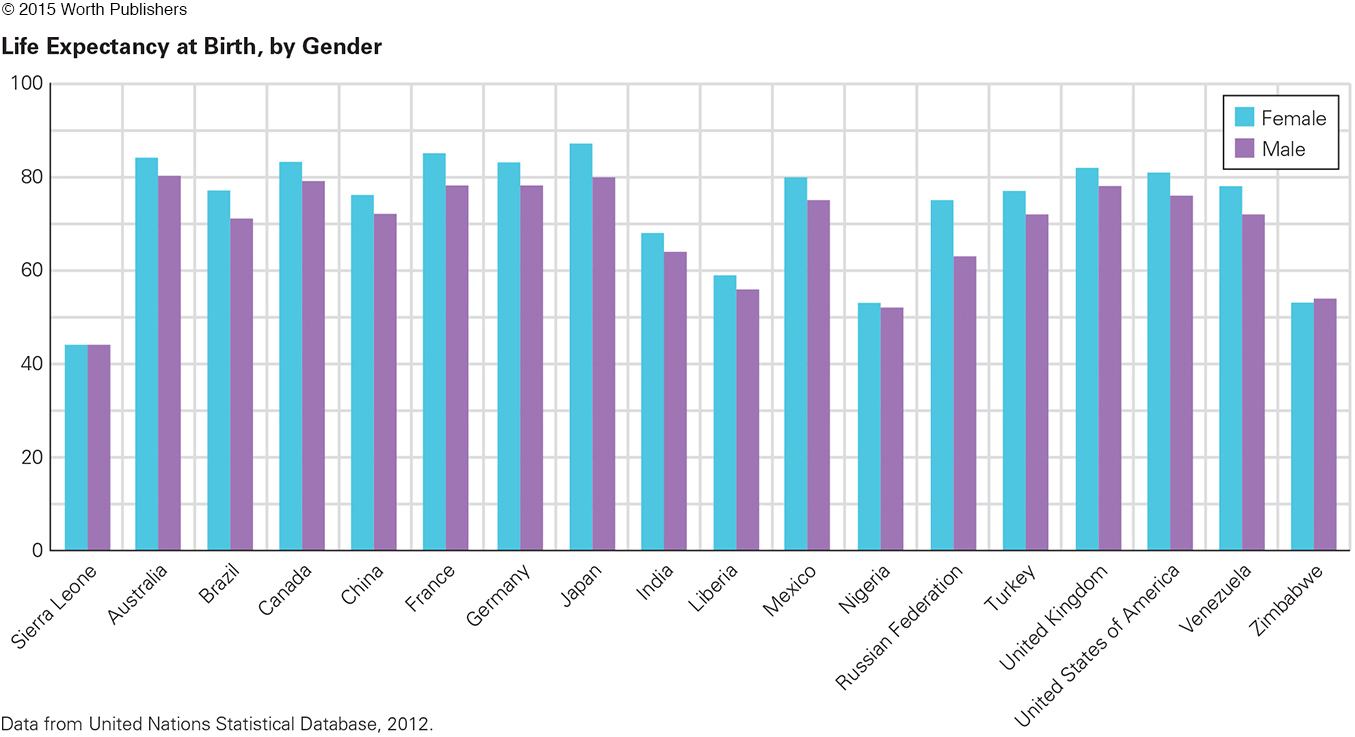

Using life itself to indicate health, people in the richest nations (e.g., Japan) live 25 years longer than those in the poorest ones (e.g., Sierra Leone) (see Figure 12.4). Or, to pick one non-

SES differences are apparent within every nation as well. For example, in the United States, adults (age 25) with a college degree live an average of nine years longer than those with no high school diploma (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). [Level of education is often used as a proxy for income, as it correlates closely.] Recent data find the SES gap widening in the United States, and health disparities follow (Olshansky et al., 2012).

Question 12.12

OBSERVATION QUIZ

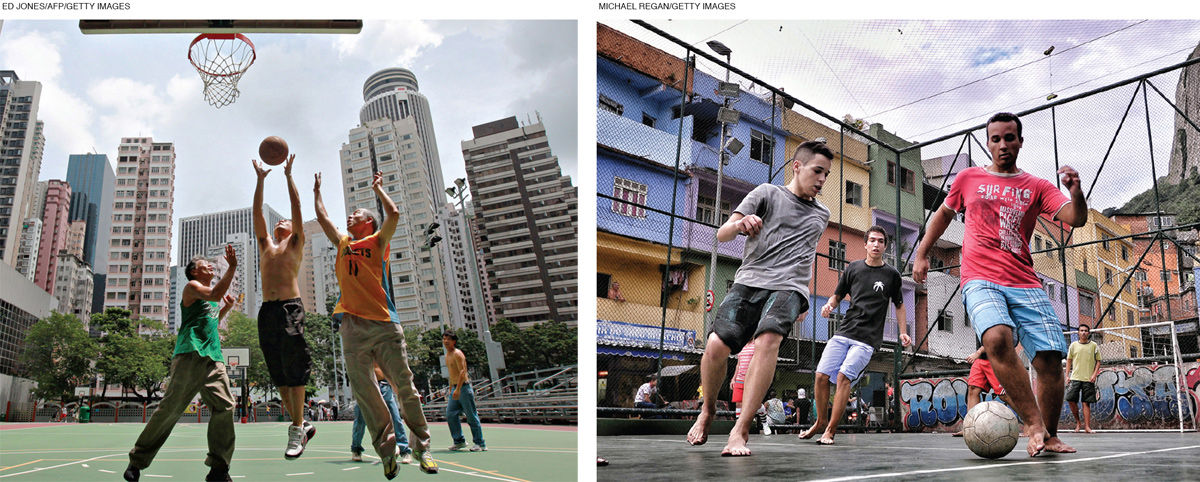

Young men everywhere play ball, but at least five cultural differences are apparent between these two scenes. What are they?

Shoes or bare feet, pants or shorts, skyscrapers or smaller buildings, basketball or soccer, large, open space or small, fenced area.

440

It is not obvious why the connection between SES and health is so strong. Does education teach better health habits? Does income allow better medical care? Do advantages cascade, such as childhood stimulation and family SES leading to college, and then degrees leading to better jobs and neighborhoods with less pollution and more places to walk, bike, and play? Do intelligent people eat better? Do wealthy people avoid stress by hiring other people to do the work they do not want to do?

Before settling on any of these explanations, consider a conundrum first explained in Chapter 2: Immigrants are usually healthier yet poorer than the native-

THINK CRITICALLY: Is there something toxic about U.S. culture that harms the poor but does not affect new immigrants?

Many explanations have been offered for the immigrant paradox. Perhaps healthy people are more likely to emigrate. Then their good health protects them despite their poverty. However, the data find that this “healthy migrant” theory is not sufficient to explain immigrant health (Bates et al., 2008; García Coll & Marks, 2012). From a developmental perspective, the most plausible explanation is social support, often very strong in new immigrant families and proven to protect health from cradle to grave (Priest & Woods, 2015).

Sex and Fertility

Another adult set of gains and losses occur with sexuality. Arousal, orgasm, and fertility are all affected by age.

SEXUAL RESPONSIVENESS Sexual arousal occurs more slowly and orgasm takes longer with senescence. However, some say that sexual responses improve with age. Could that be? Might familiarity with one’s own body and with that of one’s partner make slower response more often a joy than an anxiety?

infertility

The inability to conceive a child after trying for at least a year.

A U.S. study of women aged 40 and older found that sexual activity decreased each decade but that sexual satisfaction did not (Trompeter et al., 2012). A British study of more than 2,000 adults in their 50s found that almost all of them were sexually active (94 percent of the men and 76 percent of the women) and, again, that most were quite satisfied with their sex lives (D. Lee et al., 2015).

INFERTILITY Although sexual satisfaction may not decline with age, reproduction certainly does. Rates of infertility (often defined as failure to conceive after a year of trying) vary from nation to nation, primarily because the rate increases when medical care is scarce (Gurunath et al., 2011).

441

Age matters as well. In the United States, about 12 percent of all adult couples are infertile, partly because many postpone childbearing. Peak fertility is at about age 18.

If couples in their 40s try to conceive, about half fail and the other half risk various complications. Of course, risk is not reality: In 2011 in the United States, 116,000 babies were born to women age 40 and older, the only age group for whom the birth rate is steadily rising (Hamilton et al., 2012). Most of their babies become healthy, well-

When couples are infertile, either or both partners may be the problem. A common reason for male infertility is low sperm count. Conception is most likely if a man ejaculates more than 20 million sperm per milliliter of semen, two-

Depending on the man’s age, each day about 100 million sperm reach maturity after a developmental process that lasts about 75 days. Anything that impairs body functioning over those 75 days (e.g., fever, radiation, drugs, time in a sauna, stress, environmental toxins, alcohol, cigarettes) reduces sperm number, shape, and motility (activity), making conception less likely. Sedentary behavior, perhaps particularly watching television, also correlates with lower sperm count (Gaskins et al., 2013).

As with men, women’s fertility is affected by anything that impairs physical functioning—

ASSISTED REPRODUCTION In the past 50 years, medical advances have solved about half of all fertility problems. Surgery repairs reproductive systems, and assisted reproductive technology (ART) overcomes obstacles such as a low sperm count and blocked fallopian tubes. ART, especially IVF (in vitro fertilization), has led to an estimated 5 million births (Fisher & Giudice, 2013).

IVF is quite different from the typical conception. The woman must take hormones to increase the number of fully developed ova, and the man must ejaculate into a receptacle. Then surgeons remove several ova from one or both ovaries and technicians combine the ova and sperm in a laboratory dish, often inserting one active sperm into each normal ovum.

Success is evident a few hours later, as several zygotes form and duplicate. Then one or more healthy blastocysts are inserted into the uterus, which is ready for implantation via additional drugs. Everyone waits and hopes.

Even with careful preparation, fewer than half of the inserted blastocysts successfully implant and grow to become newborns. Age of the ova is one crucial factor, so some young women freeze their ova for IVF years later (Mac Dougall et al., 2013). Miscarriages (perhaps one in three implanted embryos) increase with age.

If IVF newborns are normal weight, they do as well or better than other babies, not only in childhood health, intelligence, and school achievement but also in self-

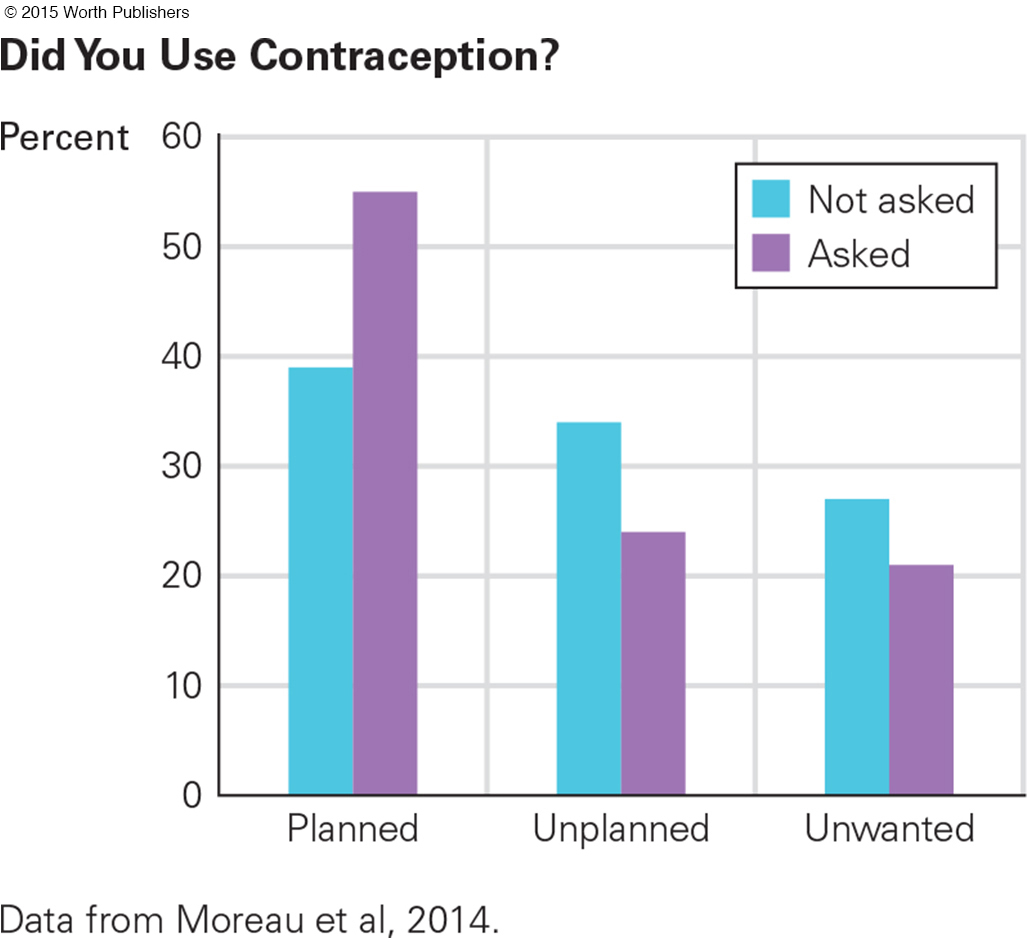

IVF children may grow well because they are planned and wanted. Of course, planning itself is cultural and contextual. National policy and culture have an effect, and traditionally, men tend to want more children than women do, although each half of a couple is affected by the fertility hopes of the other (Billingsley & Ferrarini, 2014), The availability of contraception affects planning, but even when birth control is available and free, estimating how many pregnancies are planned is complex.

442

For instance, more than 8,000 parents in France were asked whether each pregnancy was planned, unplanned (mistimed), or unwanted. Half of them were asked that simple question. The answers were: 39 percent planned, 34 percent mistimed, and 27 percent unwanted. The other half were first asked whether they had been using contraception at conception. That made 55 percent say they planned the pregnancy: 24 percent said it was mistimed and 21 percent unwanted (Moreau et al., 2014) (see Figure 12.5).

MENOPAUSE During adulthood, the level of sex hormones circulating in the bloodstream declines—

menopause

The time in middle age, usually around age 50, when a woman’s menstrual periods cease and the production of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone drops. Strictly speaking, menopause begins one year after a woman’s last menstrual period.

For women, sometime between ages 42 and 58 (the average age is 51), ovulation and menstruation stop because of a marked drop in production of several hormones. This is menopause. The precise age is affected primarily by genes (17 have been identified) (Morris et al., 2011; Stolk et al., 2012) but also by smoking (earlier menopause) and exercise (later).

In the United States, one in four women has a hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus), which may include removal of her ovaries. If she was premenopausal, removal of ovaries causes vaginal dryness and body temperature disturbance, including hot flashes (feeling hot), hot flushes (looking hot), and cold sweats (feeling chilled).

Natural menopause produces the same symptoms, but not as suddenly and not in everyone. Early menopause, surgical or not, increases the risk of health problems later on (Hunter, 2012).

The psychological consequences of menopause vary more than the physiological ones. Some menopausal women have erratic moods, others are more energetic, and still others become depressed (Judd et al., 2012). Many women are relieved that menstruation and fear of pregnancy have ended. Margaret Mead (famous anthropologist who studied women throughout the world) felt renewed energy after age 50 and called it “post-

443

andropause

A term coined to signify a drop in testosterone levels in older men, which normally results in reduced sexual desire, erections, and muscle mass. (Also called male menopause.)

Do men undergo anything like menopause? Some say yes, suggesting that the word andropause should be used to signify age-

But most experts think that the term andropause (or male menopause) is misleading because it implies a sudden drop in reproductive ability or hormones. Some men produce viable sperm and hence become new fathers at age 80 or older. Sexual inactivity and anxiety can reduce testosterone—

To combat the symptoms of the natural decline in estrogen or testosterone, some adults have turned to hormone replacement. Most physicians are wary, citing correlations between artificial hormones and breast cancer in women and heart disease in men (Zbuk & Anand, 2012; Handelsman, 2011). Nonetheless, hormones are sometimes prescribed (Samaras et al., 2012; Panay et al., 2013; Giannoulis et al., 2013). All physicians agree, however, that adult health depends more on habits than on hormones.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 12.13

1. How are people affected by the visible changes in the skin between ages 25 and 65?

During adulthood the skin becomes dryer, rougher, thinner, less flexible, and wrinkled.

Question 12.14

2. How does the ability to move the body change with age?

In the aging body, muscles atrophy; joints lose flexibility; stiffness appears; bending is harder; balance is more difficult. Rising from sitting, twisting in a dance, hoping on one foot, or even walking “with a spring in your step” is not as easy. A strained back, neck, or other body part may occur.

Question 12.15

3. How does the body shape change between ages 25 and 65?

As adults age, they tend to lose height, specifically in the trunk of the body, and experience an increase in waist circumference. During adulthood muscles typically weaken; pockets of fat settle on the abdomen, upper arms, buttocks, and chin; and adults stoop slightly when they stand.

Question 12.16

4. What is the relationship between cancer and aging?

Most cancers are affected by the health habits that increase allostatic load.

Question 12.17

5. What is the relationship between income, education, and disease in adulthood?

Money and education protect health, but it is not clear whether income or education is the main reason. Perhaps education teaches healthy habits. Or perhaps higher income allows access to better medical care as well as a home far from pollution and crime. Because low income may deprive one of access to education, it could be argued that economic factors are more important. Furthermore, diseases that were once associated with high income are now associated with low income. Individuals who are poor tend to have poorer eating habits and greater rates of obesity, more stress, bad health habits (e.g., smoking), less access to doctors, and lower-

Question 12.18

6. How are couples affected by the changes in sexual responsiveness with age?

Sexual arousal occurs more slowly with age, and orgasm takes longer. For some couples, these slowdowns are counterbalanced by reduced anxiety and better communication, as partners become more familiar with their own bodies and those of their mates. Distress at slower responsiveness seems less connected to physiological aging than to troubled interpersonal relationships and unrealistic fears and expectations. Some adults say that sexual responsiveness may improve with age; arousal and orgasm can continue throughout life. One study found that men and women who were in committed, monogamous relationships were likely to be “extremely satisfied” with sex.

Question 12.19

7. What are the causes of infertility?

As with men, women’s fertility is affected by anything that impairs physical functioning—

Question 12.20

8. How easy or difficult is the process of artificial reproductive technology?

The ART process of in vitro fertilization (IVF) is more complicated than a typical conception. The woman must take hormones to increase the number of fully developed ova, and the man must ejaculate into a receptacle. Then surgeons remove several ova from one or both ovaries and technicians combine the ova and sperm in a laboratory dish, often inserting one active sperm into each normal ovum. Even with careful preparation, fewer than half of the inserted blastocysts successfully implant and grow to become newborns.

Question 12.21

9. What are the sex differences in the decline of sex hormones with age?

In women, the level of sex hormones circulating in the bloodstream declines suddenly, while the decline is gradual for men.

Question 12.22

10. What are the advantages and disadvantages of menopause?

Disadvantages are that sexual desire and frequency of intercourse decrease, and erratic moods and depression may increase. Relief that menstruation and the possibility of pregnancy have ended is among the advantages.

444