Generativity: The Work of Adulthood

generativity versus stagnation

The seventh of Erikson’s eight stages of development. Adults seek to be productive in a caring way, often as parents. Generativity also occurs through art, caregiving, and employment.

According to Erikson, after the stage of intimacy versus isolation comes that of generativity versus stagnation, when adults seek to be productive in a caring way. Without generativity, adults experience “a pervading sense of stagnation and personal impoverishment” (Erikson, 1993, p. 267). Adults satisfy their need to be generative in many ways, especially through parenthood, caregiving, and employment.

Parenthood

Although generativity can take many forms, its chief manifestation is “establishing and guiding the next generation” (Erikson, 1993, p. 267). Many adults pass along their values as they respond to the hundreds of daily requests and unspoken needs of their children.

BIOLOGICAL PARENTHOOD The impact of parents on children has been discussed many times. Now we concentrate on the adult half of this interaction—

481

Most nonparents underestimate the generative demands of parenthood. Indeed, “having a child is perhaps the most stressful experience in a family’s life” (McClain, 2011, p. 889).

In Erikson’s view, after establishing intimacy, many adults seek generativity. A couple may choose parenthood, willingly coping with the many stresses that come with that role. Bearing and rearing children are labor-

Video: Interview with Jay Belsky explores how problematic parenting practices are transmitted (or not) from one generation to the next.

Parenthood is particularly difficult when intimacy, not generativity, is a person’s most urgent psychosocial need. As already noted, marital happiness may dip when a baby arrives, because intimacy needs must sometimes be postponed. Worse yet is having a baby as part of the search for identity (as teenagers may discover too late).

Children reorder adult perspectives. One sign of a good parent is the parent’s realization that the infant’s cries are communicative, not selfish, and that adults need to care for children more than vice versa (Katz et al., 2011).

Care can be expressed in many ways. The dynamic experience of raising children tests every parent, perhaps increasingly so when most women have jobs before they become mothers. Specifics vary from family to family, but always some adjustment is needed.

For example, a study of men and women who had been in the top 0.01 percent in math ability when they were in high school, and who had gone on to earn graduate degrees and impressive jobs decades later, found that parenthood changed both sexes. The fathers worked harder to achieve more status and income, while the mothers became more communal, focusing on community and family (Ferriman et al., 2009).

Those parents were studied a decade ago, but the same patterns persist. A 16-

482

Not always, of course, but even when roles are nontraditional, the old patterns are apparent. For example, one man became the prime caregiver for his infant and 2-

In the last generation it’s changed so much . . . it’s almost like you’re on ice that’s breaking up. That’s how I felt. Like I was on ice that’s breaking up. You don’t really know what or where the father role is. You kind of have to define it for yourself . . . I think that is what I have learned most from staying home with the kids . . . Does it emasculate me that my wife is making more money?

[Geoff, quoted in Doucet, 2015, p. 235]

Another father in the same study decided to open a business as a day-

Both these men were conscious of gender roles, even as they resisted them. Both mothers and fathers realize that raising a child requires much generative work. Social roles have changed, but children still require caregiving. Parenting becomes an ongoing challenge, because just when parents figure out how to care for their infants, or preschoolers, or schoolchildren, those children grow older, presenting new dilemmas. One exasperated mother told her criticizing teenager, “I’m learning on the job, I’ve never been a mother of an adolescent before.”

Over the decades of family life, parents must adjust to babies who disrupt sleep, toddlers who have temper tantrums, preschoolers who want to explore, schoolchildren who need help with homework or friendship or skills, teenagers who are moody, or defiant, or depressed.

Not every child presents every problem, but privacy and income rarely seem adequate, and all children need extra care and attention at some point. The more children a couple has, the more family problems arise, according to a study in many nations (Margolis & Myrskylä, 2011).

Couples usually learn to compromise or set aside their own needs to accommodate a beloved partner, but setting aside one’s assumptions is much harder when the welfare of one’s child may be affected. Children may cement a relationship, but they also may strain it.

ADOPTIVE PARENTS Roughly one-

Current adoptions are usually “open,” which means that the biological parents decided that someone else would be a better parent, but they still want some connection to the child. The child knows about this arrangement, which proves an advantage for all the adults who seek the best for the child.

Strong parent–

Sadly, some adopted children have spent their early years in an institution, never attached to any caregiver. Although some children are resilient, most are afraid to love anyone (Van IJzendoorn et al., 2011). That obviously makes child rearing more difficult for the adoptive parent. DSM-

483

As you remember, adolescence—

In attempts to upset my parents sometimes I would (foolishly) say that I wish I was given to another family, but I never really meant it. Still when I did meet my birth family I could definitely tell we were related—

[A, personal communication]

A longitudinal study of parent–

Attitudes in the larger culture often increase tensions between adoptive parents and children. For example, the mistaken notion that the “real” parents are the biological ones is a common social construction that hinders a secure relationship. International and interethnic adoptions are controversial, because some people fear that such adoptions will result in a child lost to their heritage.

Adoptive parents who take on the complications of international or interethnic adoption are usually intensely dedicated to their children. They are very much “real” parents, seeking to protect their children from discrimination that they might not have noticed before it affected their child.

For example, one European American couple adopted a multiethnic baby and three years later requested a second baby. They said, “We made a commitment [to our daughter] that we would have a brown or Black baby. So we turned down a couple of situations because they were not right” (Sweeney, 2013, p. 51). These parents had noticed strangers’ stares and didn’t want their first child to be the only dark-

Many such adoptive parents seek multiethnic family friends and educate their children about their heritage and the prejudice they may encounter. Such racial socialization often occurs within minority families for their biological children as well. When adoptive parents do so, their adolescents who encounter frequent prejudice experience less stress because they are ready to counter with pride in their background (Leslie et al., 2013).

The same is true if the child experiences discrimination because of same-

As stressed in earlier chapters, the child’s first months and years are a sensitive period for language, attachment, and neurological maturation. The older a child at adoption, the more difficult parenting that child might be (Schwarzwald et al., 2015). What may not have been sufficiently stressed is that difficult parenting is what most parents do. Parents usually are intensely devoted to their children, no matter what the child’s special needs or unusual situation. Generativity is far more powerful than what an outsider might anticipate.

STEPPARENTS Parents of stepchildren often find the experience far more complicated than they had expected. The average new stepchild is 9 years old. Typically, he or she has spent some time with both biological parents, and then with a single parent, a grandparent, other relatives, and/or a paid caregiver.

484

Changes are always disruptive for children (Goodnight et al., 2013), and the effects are cumulative, with emotions typically erupting in adolescence. Becoming a new stepparent to such a child, especially if the child is coping with a new school, loss of friends, or puberty, is difficult. Stepchildren may react by intensifying their attachment to their birth parents.

This reaction is normal and beneficial, but it hinders connections to stepparents. Any new adult who tries to be a child’s parent or friend may, understandably, trigger jealously in the absent biological parent and confusion in the child—

Stepmothers may hope to heal a broken family through love and understanding, whereas stepfathers may believe their new children will welcome a benevolent disciplinarian. Often the biological parent chose the new partner partly to give their children a better father or mother than the original one. The child may resist, partly out of loyalty.

The new stepparent may look forward to the role and expect the child to welcome a new and better mother or father. One problem is that stepparents have learned about the biological parent from a very biased reporter, namely their new spouse. Both newlyweds may expect their stepchildren to respond well to the new family.

Stepchildren rarely fulfill these hopes. Often they are hostile or distant (Ganong et al., 2011). Young stepchildren may get sick, lost, or injured accidentally, or become disruptive in school; teenage stepchildren may get pregnant, drunk, or arrested. These are all signs that the child needs special attention, but understandably stepparents may be angry and resentful rather than caring and patient. If the adults overreact, or are indifferent, the two generations become further alienated (Coleman et al., 2007).

Another complication is that stepparents know that their connection to their stepchildren depends on their relationship with their new spouse. Criticizing the children or their mate’s parenting style may harm their marriage, so many keep quiet. The better alternative is to establish a good relationship with the child, but then if the marriage dissolves, they lose a source of intimacy and generativity (Noël-

It is not surprising that stepchildren add unexpected stresses to a marriage (Sweeney, 2010). One theory is that because laws and norms are unclear about the role of stepparents, adults fight about what they expect each other to do or not do (Pollet, 2010). None of this means that stepparents cannot become generative; it does, however, warn of the difficulties.

High hopes and expectations are common, but few adults—

FOSTER PARENTS An estimated 400,650 children were officially in foster care in the United States in 2011 (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013). Many others are unofficially in foster care, because someone other than their biological parents has taken them in.

485

This is the most difficult form of parenting of all, partly because foster children typically have emotional and behavioral needs that require intense involvement. Foster parents need to spend far more time and effort on each child than biological parents do, and yet the social context tends to devalue their efforts (J. Smith et al., 2013).

Contrary to popular prejudice, adults become foster parents more often for psychosocial than financial reasons, part of the adults’ need to be needed (Geiger et al., 2013). Official foster parents are paid, but they typically earn far less than a babysitter or than they would in a conventional job.

Most children are in foster care for less than a year, as the goal is often reunification with the birth parent. The children may be moved from one placement to another, or from foster care back to the dysfunctional family, for reasons unrelated to the wishes, competence, or emotions of the foster parents. This makes it doubly hard for the foster parents to develop a generative attachment to their children, and doubly admirable when they do.

The average child entering the foster-

However, if birth parents are so neglectful or abusive that foster care is needed, the child’s early insecure or disorganized attachment to their birth parents impedes relationships with the foster parent. Most foster children have experienced long-

As a result, adult caregivers of such children, either in foster families or institutions, face the dilemma of “whether to ‘love’ the children or maintain a cool, aloof posture with minimal sensitive or responsive interactions” (St. Petersburg–

For all forms of parenting, generative caring does not occur in the abstract; it involves a particular caregiver and care receiver. That means everything needs to be done to encourage attachment between the foster parent and child, including stable placement and support for foster parents.

GRANDPARENTS As already mentioned, the empty-

Especially when the grandchildren’s parents are troubled, grandparents worldwide believe their work includes helping their grandchildren (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012). Specifics depend on policies, customs, gender, past parenting, and income of both adult generations, but for every adult, the generative impulse extends to caring for the youngest generation.

Currently in developed nations, most grandparents try to be easygoing and helpful, partly because all three generations expect them to be companions, not authorities. This requires the older adult to learn a new role: One grandmother said her tongue was scarred because she had to bite it so often (Holmes & Nash, 2015).

The supportive role is not unwanted. Grandparents prefer to provide occasional babysitting and emergency financial help but not advice or discipline (May et al., 2012). Grandparents want to be intensely generative, but they realize that support requires granting independence and autonomy.

486

Again, do not confuse residence with emotional closeness. Poverty, more than family harmony, is the main reason some grandparents live with their children and grandchildren. In extended families, the mother still provides most of the child care. Of course, much depends on specific needs and abilities: In about a third of three-

About 1 percent of all U.S. households are two-

Even more than grandfathers, many grandmothers prioritize the welfare of their children and grandchildren. In Maslow’s hierarchy, they ignore their own basic food and shelter needs, or love and companionship needs, to ensure the success of the younger generations. That may explain why caregiving grandmothers who are surrogate parents for their grandchildren are usually less healthy and less happy than their peers from the same neighborhoods (Chen et al., 2014; Shakya et al., 2012; Muller & Litwin, 2011).

If a grandmother is employed, as many of those under age 65 now are, she is likely to retire early if grandchildren come to live with her. Otherwise, balancing the needs of the youngest generation with the needs of a job reduces her own well-

When my daughter divorced, they nearly lost the house to foreclosure, so I went on the loan and signed for them. But then again they nearly foreclosed, so my husband and I bought it. . . . I have to make the payment on my own house and most of the payment on my daughter’s house, and that is hard . . . I am hoping to get that money back from our daughter, to quell my husband’s sense that the kids are all just taking and no one is ever giving back. He sometimes feels used and abused.

[quoted in Meyer, 2014, pp. 5, 6]

Especially when one of the children or grandchildren is seriously ill or disabled, grandmothers often help despite the grandfather’s wishes (Meyer, 2012).

In general, skipped-

But before concluding that grandparents suffer when they are responsible for grandchildren, consider China, where many grandparents (almost always under age 65) become full-

This discussion of grandparents who live with their grandchildren should not obscure the general fact that most grandparents enjoy their role, gain generativity from it, and are appreciated by younger family members. Some are even rhapsodic and spiritual about the experience. As one writes:

Not until my grandson was born did I realize that babies are actually miniature angels assigned to break through our knee-

[Golden, 2010, p. 125]

Caregiving

487

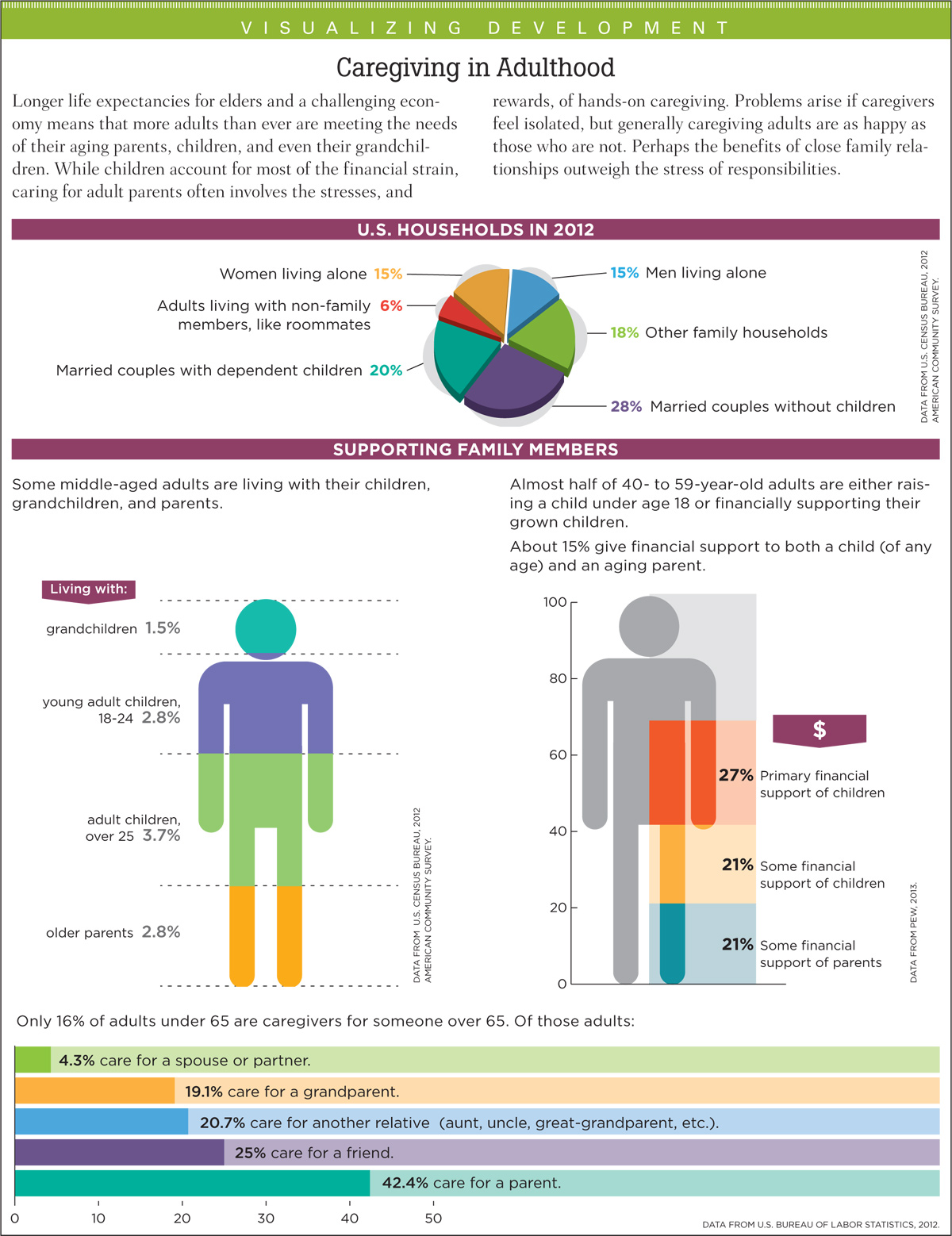

Parenting is the most common form of generativity for adults, but caregiving can and does occur in many other ways as well. Indeed, “life begins with care and ends with care” (Tally & Montgomery, 2013, p. 3).

Erikson (1993) wrote that a mature adult “needs to be needed” (p. 266). Some caregiving requires meeting physical needs—

kinkeeper

Someone who becomes the gatherer and communication hub for their family.

KINKEEPERS A prime example of caregiving in most multigenerational families is the kinkeeper, a person who gathers everyone for holidays; spreads the word about anyone’s illness, relocation, or accomplishments; buys gifts for special occasions; and reminds family members of one another’s birthdays and anniversaries (Sinardet & Mortelmans, 2009). Guided by their kinkeeper, all the relatives become more generative.

Fifty years ago, kinkeepers were almost always women, usually the mother or grandmother of a large family. Now families are smaller and gender equity is more apparent, so some men or young women are kinkeepers. Generally, however, most kinkeepers are still middle-

Sometimes one family member is called on to do more than keep the family together. Because of their position in the generational hierarchy, middle-

sandwich generation

The generation of middle-

Middle-

Far from being squeezed, middle-

488

When adult children take care of their adult parents, the manifestation of care is not usually financial, but cultural. They help their parents understand music, media, fashion, and technology—

I have often experienced this in my family. For years, one of my adult daughters insisted that my Christmas present to her was for me to have a mammogram. Another daughter said that my present to her should be to allow her to take me clothes shopping for myself. She told me what to try on and what to buy. All I had to do was to pay for my own new clothes.

As for caregiving in the other direction, from middle-

Instead, every adult of a family cares for every other one, each in their own way. The specifics depend on many factors, including childhood attachments, personality patterns, and the financial and practical resources of each generation. Mutual caregiving strengthens family bonds; wise kinkeepers share the work, allowing everyone to be generative.

CULTURE AND CAREGIVING Some cultures assume that elderly parents should live with their adult children and that unmarried adults should live with their parents. National and ethnic variations are evident in how interdependent family members are expected to be. Some families expect to see each other often and share food, money, child care, shelter, and so on. Although people may assume that closeness means affection, such closeness may increase conflict (Voorpostel & Schans, 2011).

Regarding elder care specifically, cultures differ as to which child is responsible. The traditional assumption in Asian nations is that the eldest son and his wife provide for parents, whereas unmarried daughters are the prime caregivers in most Western nations. This varies from one family to another within each culture. For instance, in mainland China, if an elderly person lives with an adult child, it is usually with a son, but in Taiwan it is usually with a daughter (Chu et al., 2011).

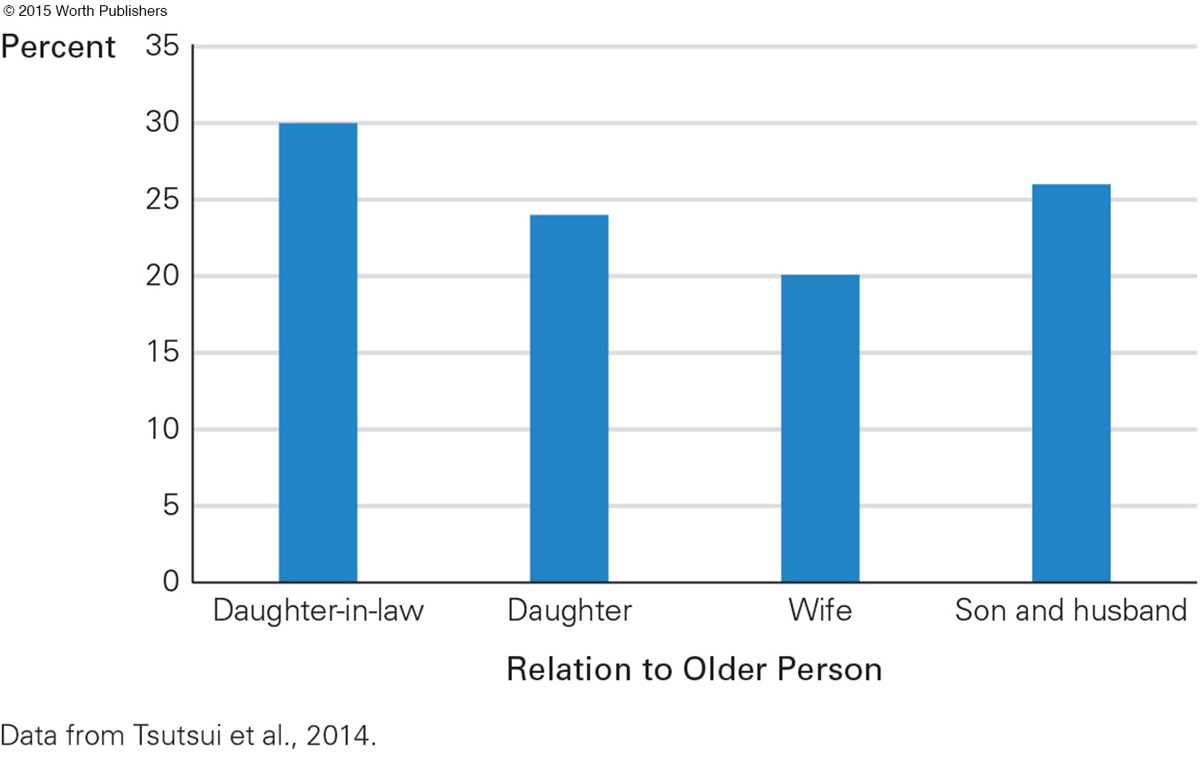

The traditional custom of a frail older person living with their eldest son and being cared for by the son’s wife was apparent in a survey of elders needing care in one Japanese city (see Figure 13.2). Almost a third (30 percent) were cared for by a daughter-

The Japanese daughter-

One study examined how the law changed Japanese caregivers’ sense of filial obligation Tsutsui et al., 2014). Even before the law, more people “slightly agreed” than “agreed” that adult children should provide financial, physical, and emotional care for the elderly. Those least likely to agree were the older women themselves who had seen how that norm had burdened their cohort. Two years after the law, the sense of filial obligation had decreased, especially among the daughters-

489

In Japan, as in the United States, the elderly who do not live with their grown children tend to be healthier. Similar changes are found in other Asian nations, including Korea and Taiwan, but not in every Asian nation. For example, most of the elderly in India live with their children and grandchildren and are healthier because of it. The elderly Indians who live alone, or only with a spouse, tend to get sick more often (Samanta et al., 2014).

Further discussion of the care needs of the aged occurs in Chapter 15. Here it is notable that adults tend to be more willing to give care than receive it: Middle-

One last observation on caregiving and care-

Employment

Besides parenthood and caregiving, the other major avenue for generativity is employment, a topic neglected by many developmentalists until recently. Some important work has been done regarding job choice, helping people find the right career that fits with their personality. Beyond that, most social science research on jobs has considered economic productivity, which has improved efficiency of workers, markets, and investments.

That is important work, because for optimal human development, a thriving economy helps. Then people are less likely to starve and suffer, and more likely to have everything from clean water to high-

However, productivity is not central to our study of adult development. We focus instead on the psychological costs and benefits of employment for the workers.

GENERATIVITY AND WORK As is evident from many terms that describe healthy adult development—

Work meets these needs by allowing people to do the following:

Develop and use their personal skills.

Express their creative energy.

Aid and advise coworkers, as mentor or friend.

Support the education and health of their families.

Contribute to the community by providing goods or services.

extrinsic rewards of work

The tangible benefits, usually in salary, insurance, pension, and status, that come with employment.

intrinsic rewards of work

The personal gratifications, such as pleasure in a job well done or friendship with coworkers, that accompany employment.

These facts highlight the distinction between the extrinsic rewards of work (the tangible benefits such as salary, health insurance, and pension) and the intrinsic rewards of work (the intangible gratifications of actually doing the job). Generativity is intrinsic.

490

491

The power of these rewards is affected by age. Extrinsic rewards tend to be more important when young people are first hired (Kooij et al., 2011). After a few years, in a developmental shift, the intrinsic rewards of work, especially relationships with coworkers, become more important (Inceoglu et al., 2012).

The power of intrinsic rewards explains why older employees are, on average, less often absent or late, and more committed to doing a good job, than younger workers are (Rau & Adams, 2014). Because of seniority, they also have more control over what they do, as well as when and how they do it. (Autonomy reduces strain and increases dedication.) Further, experienced workers are more likely to be mentors—

Some people think older workers are less motivated to work. However, the research finds that they are as motivated as younger workers, although specifics may differ (Ng & Feldman, 2012). Especially at older ages, pride in a job well done and the joy at the final product (which might be a satisfied customer or client) are important parts of job satisfaction.

Surprisingly, absolute income (whether a person earns $30,000 or $40,000 or even $100,000 a year, for instance) matters less for job satisfaction than how a person’s income compares with others in their profession or neighborhood, or to their own salary a year or two ago. It is a human trait to react more strongly to personal losses than to personal gains, ignoring systemic losses unless they become personal (Kahneman, 2011). Consequently, salary cuts have emotional, not just financial, effects.

The sense of unfairness is innate and universal, encoded in the human brain (Hsu et al., 2008). Awareness of this fact helps explain some of the attitudes of adults about pay. For example, a detailed longitudinal study of nursing assistants who stayed or left their jobs over a one-

For adults of any age, unemployment—

Some of the specific data are troubling, given that unemployment reached almost 10 percent in the United States in 2009, and 20 percent in several European nations. Adults who can’t find work are 60 percent more likely to die than other people their age, especially if they are younger than 40 (Roelfs et al., 2011); twice as likely to be clinically depressed (Wanberg, 2012); and almost twice as likely to be drug-

A meta-

Moreover, most Americans are aware that a large gap exists between the rich and the poor. They wish that the income distribution were less skewed. However, relatively few consider this a major problem (Norton & Ariely, 2011). Given that a sense of fairness is innate, many psychologists wonder why. One answer is that people believe that social mobility is possible, that they themselves will be able to earn more (Davidai & Gilovich, 2015).

492

Apparently, resentment about work arises not directly from wages and benefits but from how wages are determined and whether or not a person believes that income or status might improve. If workers have a role in setting wages and they perceive those wages are fair, they are more satisfied (Choshen-

THE CHANGING WORKPLACE Obviously, work is changing in many ways that affect adult development. We focus here on only three—

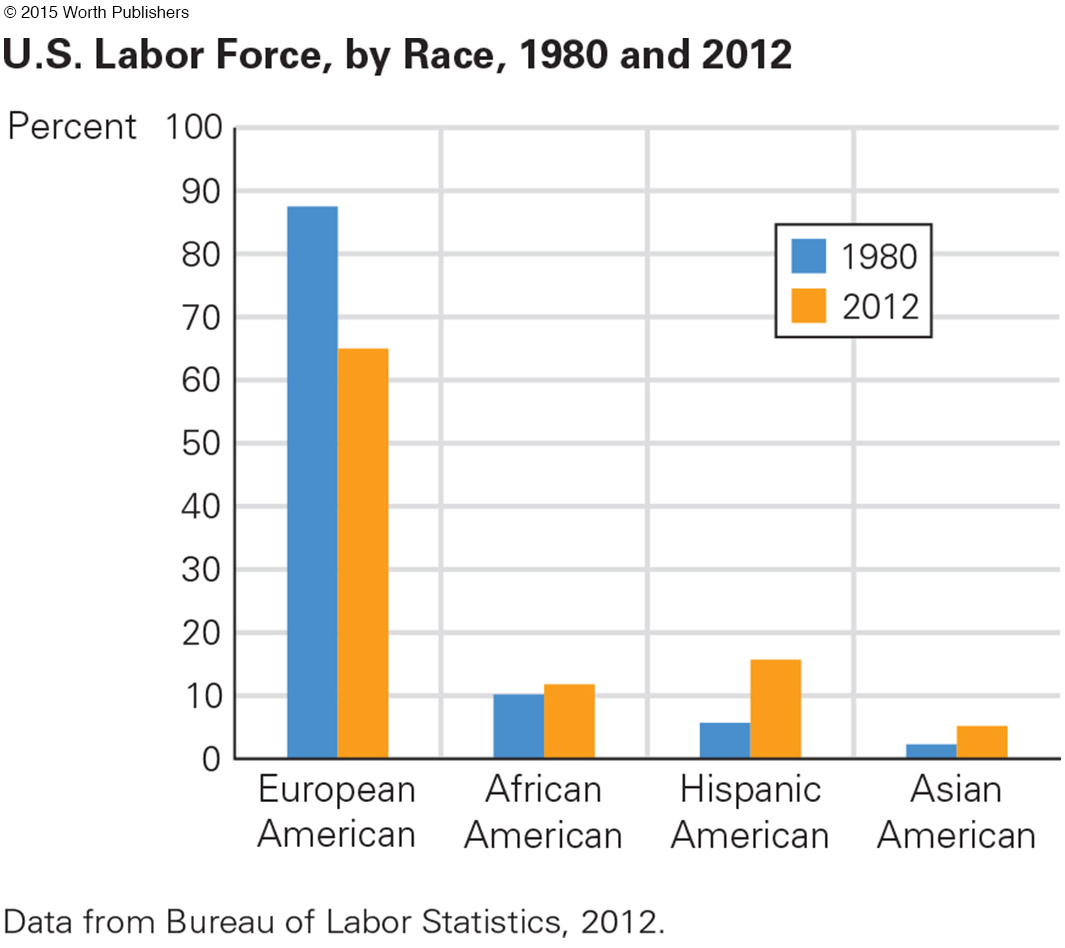

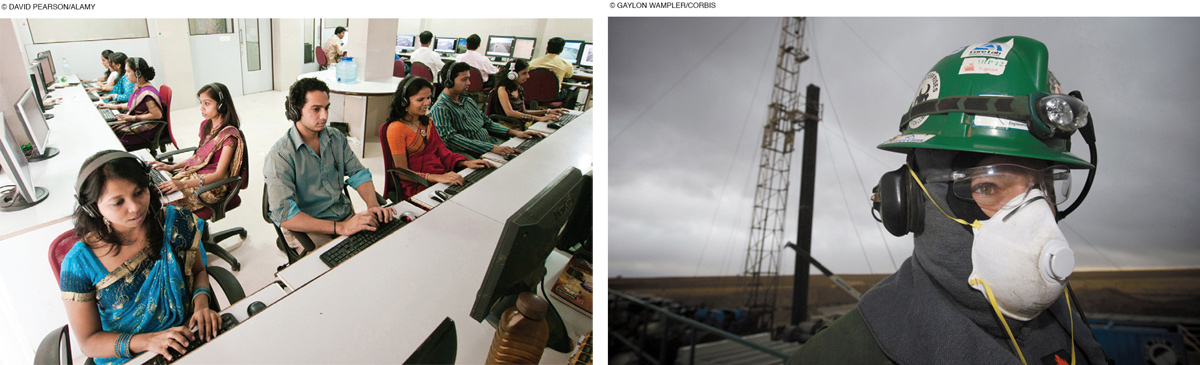

Fifty years ago, the U.S. civilian labor force was 74 percent male and 89 percent non-

Question 13.21

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Does this graph indicate that, in 2012, a European American adult was six times more likely to be employed than an African American adult?

No. Remember that the percentage of adults who are African American is about 13 percent. Chance of employment is almost equal for adults of every ethnicity. Inequality is most evident in salary and type of work, not in employment itself.

This shift is also notable within occupations. For example, in 1960, male nurses and female police officers were rare, perhaps 1 percent. Now 13 percent of registered nurses are men and 9 percent of police officers are women—

Such changes benefit millions of adults who would have been jobless in previous decades, but it also requires workers and employers to be sensitive to differences they did not notice. Younger adults may have an advantage, because they are more likely to accept diversity—

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Accommodating Diversity

Accommodating the various sensitivities and needs of a diverse workforce requires far more than reconsidering the cafeteria menu and the holiday schedule. Private rooms for breast-

Supervisors of European descent in New Zealand criticize Maori workers (descendent from the dark-

What might those “reasons behind” be? For British New Zealanders, a funeral of a cousin might take a day. Employees from that culture resent that a Maori coworker might take not only the allotted day but much longer, appearing back at work a week or more later.

Yet the Maori were expected by their families to stay for several days: It would be disrespectful to leave quickly. The cultural clash regarding work schedules and family obligations led to anger.

493

Less obvious examples occur daily, at every workplace. Certain words, policies, jokes, or mannerisms seem innocuous to one group but hostile to others.

Women object to sexy pin-

up calendars in construction offices— something male workers once accepted as routine. Exchanging Christmas presents may be troubling to those who are Jehovah’s Witnesses, or to those who are not Christian.

Resentment may stir if a man calls a woman “honey,” or if a supervisor creates a nickname for an employee with a hard-

to- pronounce name.

Researchers have begun to explore micro-

The question “where are you from?” may seem innocent, or even friendly, but it implies that someone is not from the nation in which they live. This question may be micro-

Micro-

To create a workplace that respects diversity, mutual effort is needed. Not only must everyone learn about sensitivities and customs, but also everyone must adjust and communicate.

When something insensitive occurs, the offended person should not nurse a resentment but instead should speak up. Then, the listener should not take offense at a prickly misinterpretation but should instead remember how we all react when hot buttons are pushed.

It may help to realize that we all adjust to each other in our close relationships. Romantic partners change personal habits that the other does not like; family members are careful when they discuss politics, or religion, or sex; close friends are chosen because they understand vulnerabilities.

Such awareness is part of flexible adult cognition: Adults learn to how to relate to each other in families; they need to practice the same skills at work. To return to the example in New Zealand, a Maori employee could ask for, and the supervisor could grant, a much longer time to spend with their family and tribe. Then the employee could make it a priority to return on the promised day. Less resentment, more learning, happier workers.

CHANGING LOCATIONS Today’s workers change employers more often than did workers decades ago. Hiring and firing are common. Employers constantly downsize, reorganize, relocate, outsource, or merge. Loyalty between employee and employer, once assumed, now seems quaint.

These changes may increase corporate profits, worker benefits, and consumer choice. However, churning employment may harm human development. Every change severs work friendships and adds stress. Workers new to a job experience more stress than joy. One study found that people who frequently changed jobs by age 36 were three times more likely to have health problems by age 42 (Kinnunen et al., 2005). This study controlled for smoking and drinking; if it had not, the health impact would have been greater.

As adults age, losing a job becomes increasingly stressful for several reasons (Rix, 2011):

Seniority brings higher salaries, more respect, and greater expertise; workers who leave a job they have had for years lose these advantages.

Many skills required for employment were not taught decades ago, so older workers are less likely to be hired or promoted in a new job.

Age discrimination is illegal, but workers believe it is widespread. Even if age discrimination is absent, stereotype threat undercuts successful job searching.

Relocation reduces long-

standing intimacy and generativity.

From a developmental perspective, this last factor is crucial. Imagine that you are a 40-

494

If you were unemployed and in debt, and a new job was guaranteed, you might make the move. You would leave your friends and community, but at least you would have a paycheck.

But would your spouse and children quit their jobs, schools, and social networks to move with you? If not, you would be cut off from all your social support, but if they did, their food and housing would be expensive, their schools overcrowded, and their lives lonely (at least initially). For you and anyone who comes with you, moving means losing intimacy—

Such difficulties are magnified for immigrants, who make up about 15 percent of the U.S. adult workforce and 22 percent of Canada’s. Many of them depend on other immigrants for housing, work, and social connections (García Coll & Marks, 2012). That meets some of their intimacy and generativity needs, but their relationship to their family of origin and childhood friends are strained by distance; the climate, the food, and the language are not comforting.

These developmental needs are ignored by most business owners and by many workers themselves. However, adults’ intimacy and generatively needs are best satisfied by a thriving social network, and each particular community and workplace fosters that. When that is disrupted, both psychological and physical health suffers.

CHANGING SCHEDULES The standard work week is 9 A.M. to 5 P.M., Monday through Friday—

Work schedules vary by income and age, with the impact on human development rarely considered by employers or recognized by employees. Therefore, that is our focus here.

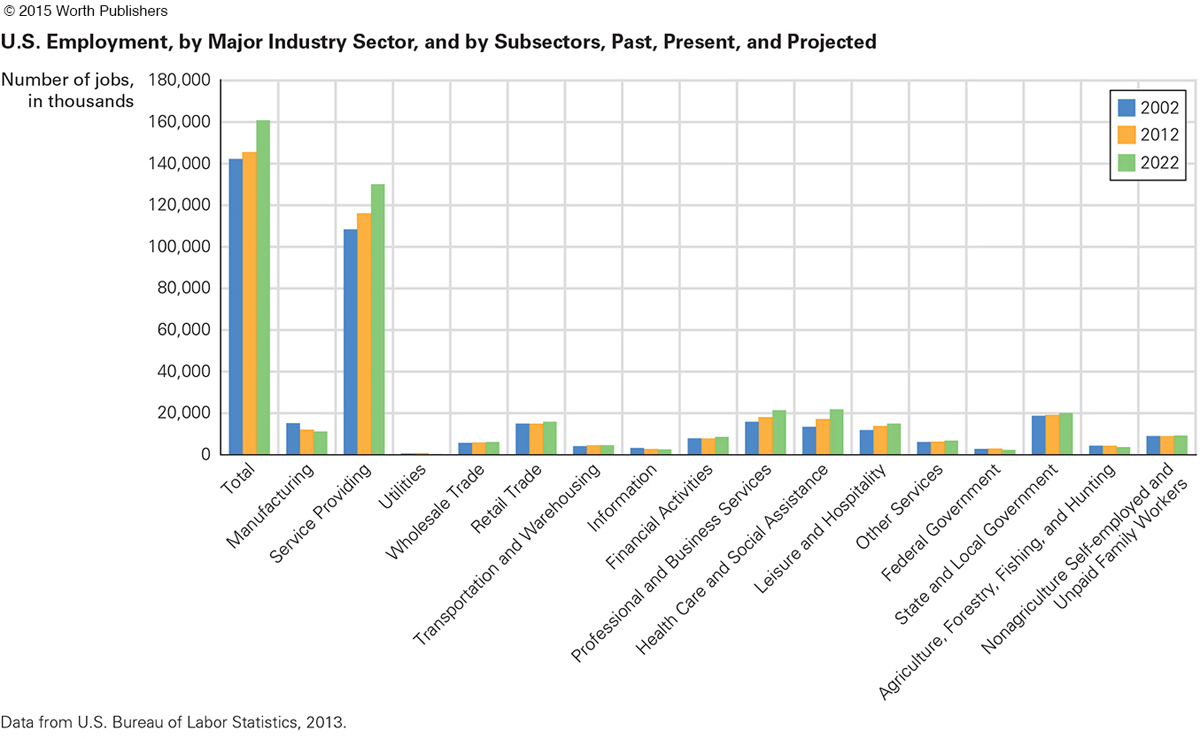

Most U.S. workers are in the service sector of the economy (80 percent, see Figure 13.4). Younger service workers, particularly in retail sales (15 million jobs) and health (14 million jobs), often have nonstandard shifts. Those segments are also the fastest growing, so increasingly new workers will find jobs with nonstandard shifts (Henderson, 2013).

The estimate in the first paragraph of this discussion (one-

495

Uncertainties arise because of definition and participants: Low-

In any case, if parents work nonstandard shifts, their families suffer because of it. Weekend work, especially with mandatory overtime, is difficult for father–

Negative effects for nonstandard work are not inevitable: Some benefits come from more income and a stronger parental alliance. The main family advantage, of course, is that nonstandard shifts may allow at least one parent to be home all the time. Nonetheless, married parents rarely benefit from nonstandard schedules, and cohabiting parents almost never do. Work requirements undercut the needs of a romantic relationship (Liu et al., 2011).

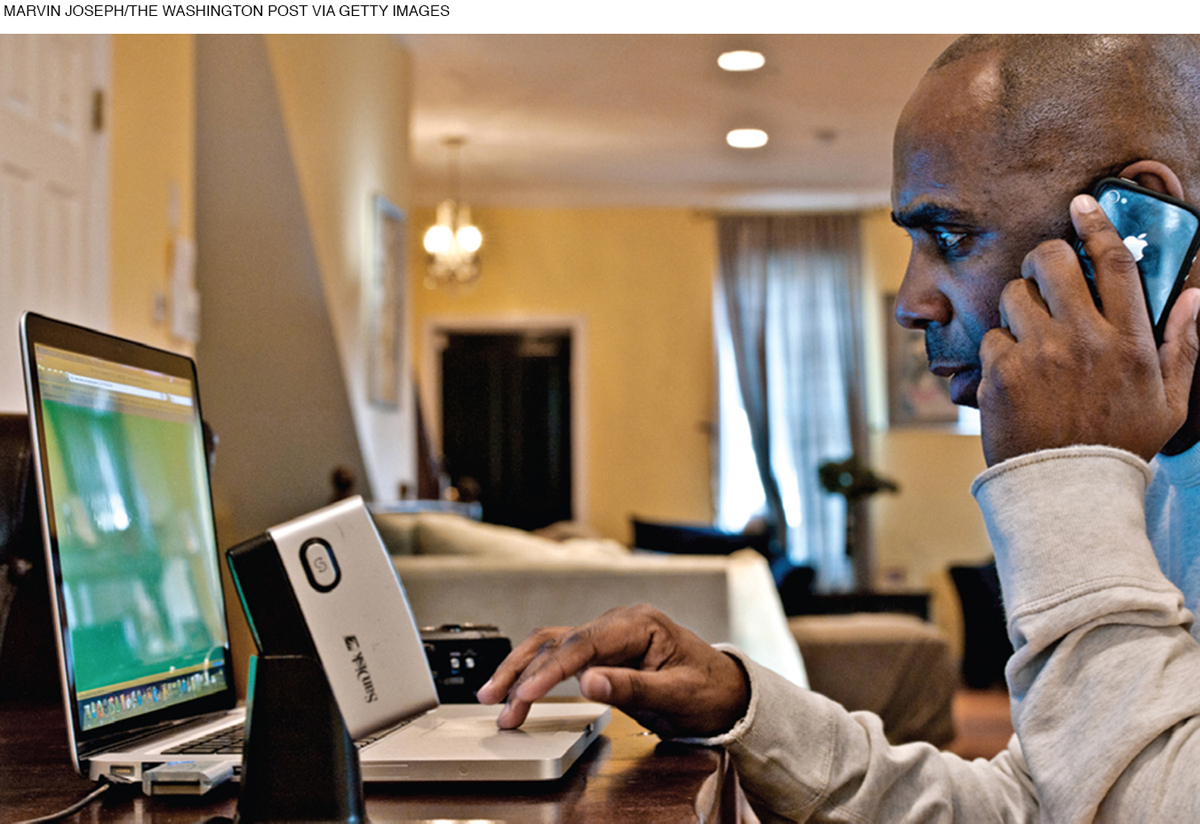

A different problem more often arises for skilled, higher-

496

However, with more skills and responsibilities also come more demands: Many such workers find that they work, sometimes “on call,” on evenings and weekends. The boundaries between work life and family life are porous, as a text message at home can interrupt family time with an unanticipated deadline, last-

One crucial variable for job satisfaction for both skilled and unskilled workers is whether employees can choose their own hours and work demands. Workers who volunteer for paid overtime are usually satisfied, but workers who are required to work overtime are not (Beckers et al., 2008). This is true no matter how experienced the workers are, what their occupation is, or where they live (Tuttle & Garr, 2012).

For instance, a nationwide study of 53,851 nurses, ages 20 to 59, found that required overtime was one of the few factors that reduced job satisfaction in every cohort (Klaus et al., 2012). Similarly, a study of office workers in China also found that the extent of required overtime correlated with less satisfaction and poorer health (Houdmont et al., 2011). Apparently, although work (paid or unpaid) is satisfying, working too long and not by choice undercuts the psychological and physical benefits.

In theory, part-

FINDING THE BALANCE As you see, adulthood is filled with opportunities and challenges. Adults can finally choose their mates, their locations, their lifestyles to express their personality, with the extroverts surrounding themselves with many social activities and the introverts choosing a more quiet, but no less rewarding, life.

Both men and women have intimacy and generativity needs, and both sexes have many ways to meet those needs. Intimacy can occur with partners of the same sex or other sex, marriage or cohabiting, friends and family, parents or siblings or grown children, or, ideally some chosen combination of all that. Similarly, generativity can focus on raising children or employment. Again, modern life often allows men and women to meet their needs in both arenas at once, as more men are active fathers and more women are employed.

In some ways, then, modern life allows adults to “have it all,” to combine family and work in such a way that all needs are satisfied at once. However, some very articulate observers suggest that “having it all” is an illusion or, at best, a mistaken ideal achievable only by the very rich and very talented (Slaughter, 2012; Sotomayor, 2014), as the following explains.

A CASE TO STUDY

Having It All

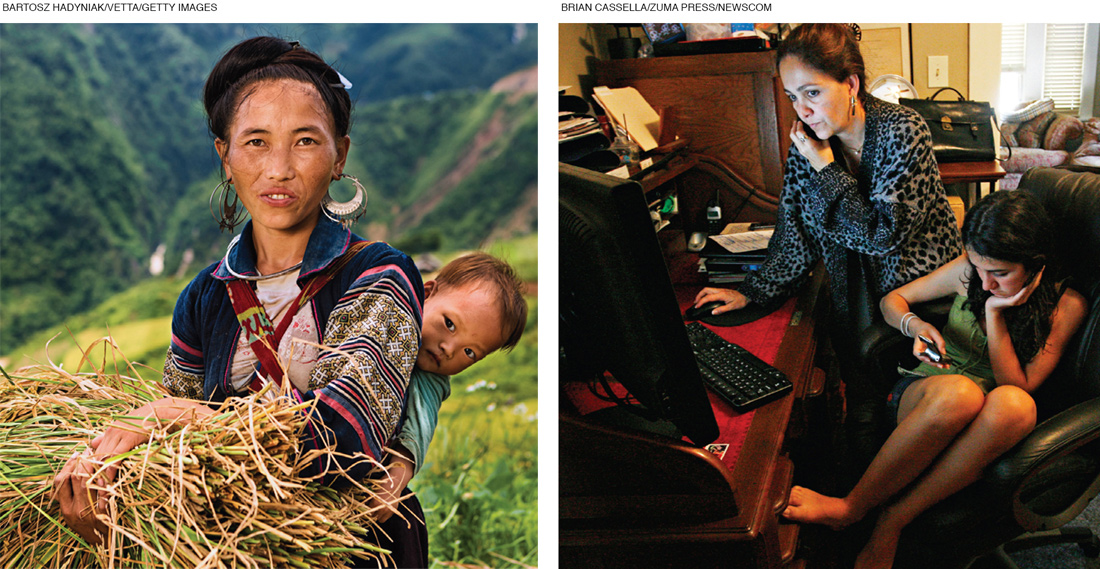

Gender and child care have changed markedly in the past half-

In every nation, child care consumes more time and thought from women than men, and males have more power and pay than females. It is not hard to find exceptions to these generalities—

497

Many feminists conclude that the “revolution has stalled,” that progress toward gender equity in the last decades of the twentieth century has halted in the first decades of the twenty-

Are social structures and cultural patterns keeping women from professional success, forcing them to choose between dedication to motherhood and dedication to their jobs? Or are women handicapping themselves by their actions and attitudes? We present two cases, both highly successful women with two children. One concludes that women could “have it all” if only society would change.

Anne-

Eighteen months into my job as the first woman director of policy planning at the State Department, a foreign-

[Slaughter, 2012, p. 84]

Slaughter left that “dream job” in Washington, D.C., six months later to be closer to her children in New Jersey. She still believes that men and women can “have it all,” with satisfying work and thriving families, but she does not think that possible today. Only if a mother has work where she controls the schedule, a job that requires little travel or evening work, can she be a good mother and employee.

The problem as Slaughter sees it is that society is still geared to the old days, when mothers stayed home with the children. What needs to happen is “changing social policies and bending career tracks to accommodate our choices” (Slaughter, 2012, p. 102).

Another extremely successful woman, Sheryl Sandberg, the chief operating officer of Facebook, says that “having it all” is a myth, never possible. She says, “I fall very short of doing it all” (Sandberg, 2013, p. 139). When women are less successful in the world of work, she argues that the problem is that women hold themselves back; they lean away from challenges rather than “lean in,” because “stereotypes and biases cloud our beliefs and perpetuate the status quo” (Sandberg, 2013, p. 159).

Sandberg thinks it is folly when any man or woman believes they can do everything well all the time. But it is even more destructive for women to believe they are less capable of doing work as well as any man. Misguided belief leads to less ambition and then less success: Women need to believe in themselves, says Sandberg.

As you see, the essential controversy here is whether women are held back by society or by their own stereotypes.

There is a third perspective: that some gender differences are as they should be. The idea is that, since only females can become pregnant and nurse their children, it is natural for women to provide more child care. Men are designed, biologically, to brave the outside, competitive world: Their testosterone leads them to the top of many professions, as it should.

Which of these perspectives seems right to you? What would you like to read in a case study of you?

Compromises, trade-

For example, a large study of adult Canadians found that about half of the variation in their distress was related to employment (working conditions, support at work, occupation, job security), but at least as much was related to family issues (having children younger than 5, support at home) and feelings of personal competence (Marchand et al., 2012).

In linked lives, husbands and wives usually adjust to each other’s needs, allowing them to function better as a couple than they did as singles (Abele & Volmer, 2011). When they become parents, men spend more hours on the job and women more hours at home. Consequently, five years after their wedding the man’s salary is notably higher than it would have been if he were single, while their shared home is notably more accommodating (Kuperberg, 2012). Thus, people help each other with the problems of adulthood, together balancing generativity needs.

498

Grandparents, too, help with balance. If parents have reliable, nearby grandparents, they are likely to have more children, and the children they have are likely to do better in school and, later on, in college and life.

Do adults fare better or worse with today’s economic climate and social norms? As you see, alternatives to marriage, nonbiological parenthood, workplace diversity, job changes, and schedule variation have benefits as well as costs. For example, maternal employment is more likely to benefit families than not, but children still need parental attention—

Because personality is enduring and variable, opinions about current adult development reflect personality as well as objective research. Some people are optimists—

Data could be used to support both perspectives. For instance, in the United States, suicide is less common than it used to be (life is better), but the gap between rich and poor is increasing (life is worse). Fewer people are marrying and fewer children are born: Is that evidence for improved adult lives or the opposite?

From a developmental perspective, personality, intimacy, and generativity continue to be important in every adult life. Further, every adult benefits from friends and family, caregiving responsibilities, and satisfying work. Whether finding a satisfying combination of all of this is easier or more difficult at this historical moment is debatable.

As the next two chapters detail, there are many possible perspectives on life in late adulthood as well. Some view the last years of life with horror, others consider them golden. Neither view is quite accurate, as you will soon see.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 13.22

1. What is the basic idea of generativity?

Generativity refers to the need to be productive in a caring way. Without generativity, adults experience “a pervading sense of stagnation and personal impoverishment.” Adults satisfy their need to be generative in many ways, including through parenthood, caregiving, and employment.

Question 13.23

2. In what ways does parenthood satisfy an adult’s need to be generative?

Childbearing and rearing is a labor-

Question 13.24

3. What factors might make it difficult for foster children and foster parents to bond?

Children may be put into foster care if birth parents are so neglectful or abusive that the children are seriously harmed by their care. In these cases the child’s early attachment to their birth parents can impede connection to the foster parent. Furthermore, a secure new attachment may be hampered if both adult and child know that their connection can be severed for reasons unrelated to caregiving quality or relationship strength.

Question 13.25

4. How might each of the Big Five personality traits make it easier or more difficult to develop positive relationships with stepchildren?

Someone high in openness may be more willing to deal with the new experience of stepparenting. A person high in conscientiousness might not like the disorder that stepchildren bring to a family. A person high in extroversion and/or agreeableness may have an easier time relating to and accepting stepchildren. A person high in neuroticism may not be able to tolerate the increased anxiety that may come with caring for stepchildren.

Question 13.26

5. What advantages do adoptive parents have over foster parents or stepparents?

Adoptive parents are legally connected to their child for life and typically they desperately wanted the child. Both of these factors may lead to a strong parent–

Question 13.27

6. Is it a blessing or a burden that women are more often kinkeepers and caregivers than are men?

The role of being the kinkeeper (a caregiver who takes responsibility for maintaining communication) may be burdensome, but caregiving provides both satisfaction and power. Kinkeepers may share the work; shared kinkeeping is an example of generativity.

Question 13.28

7. Why are middle-

Middle-

Question 13.29

8. What are some extrinsic and intrinsic rewards of work?

Extrinsic rewards of work include tangible benefits such as salary, health insurance, and a pension or retirement savings. Intrinsic rewards of work are related to generativity; satisfaction, relationships with coworkers, and a sense of participation in meaningful activity.

Question 13.30

9. What are the advantages of greater ethnic diversity at work?

Greater ethnic diversity is a benefit to those people who would not have been hired in previous decades. The greater diversity also requires employers to be sensitive to differences they might not have noticed previously. Employees benefit from working with a variety of coworkers and supervisors.

Question 13.31

10. Why is changing jobs stressful?

1) Seniority brings higher salaries, more respect, and greater expertise; workers who leave a job they have had for years lose these advantages. 2) Many skills required for employment were not taught decades ago, so older job seekers are less likely to be hired. 3) Age discrimination is illegal, but workers believe it is widespread. Even if it does not exist, stereotype threat undercuts successful job searching. 4) Relocation reduces long-

Question 13.32

11. How have innovations in work scheduling helped and harmed families?

Flextime, telecommuting, part-

Question 13.33

12. Why, overall, might people be happier with current employment patterns than earlier ones?

Non-