The Frail Elderly

frail elderly

Older adults who are severely impaired, usually unable to care for themselves.

Now that we have dispelled stereotypes by describing most aging adults as active, enjoying supportive friends and family, we can turn to the frail elderly—those who are infirm, inactive, seriously disabled, or cognitively impaired. Frailty is not defined by any single disease, no matter how serious, but by an overall loss of energy and strength. It is systemic, often accompanied by weight loss and exhaustion.

The frail are not the majority. Typically, older people are happy and active for decades, but eventually about one-

Activities of Daily Life

activities of daily life (ADLs)

Typically identified as five tasks of self-

One way to measure frailty, according to insurance standards and medical professionals, is by assessing a person’s ability to perform the tasks of self-

instrumental activities of daily life (IADLs)

Actions (for example, paying bills and driving a car) that are important to independent living and that require some intellectual competence and forethought.

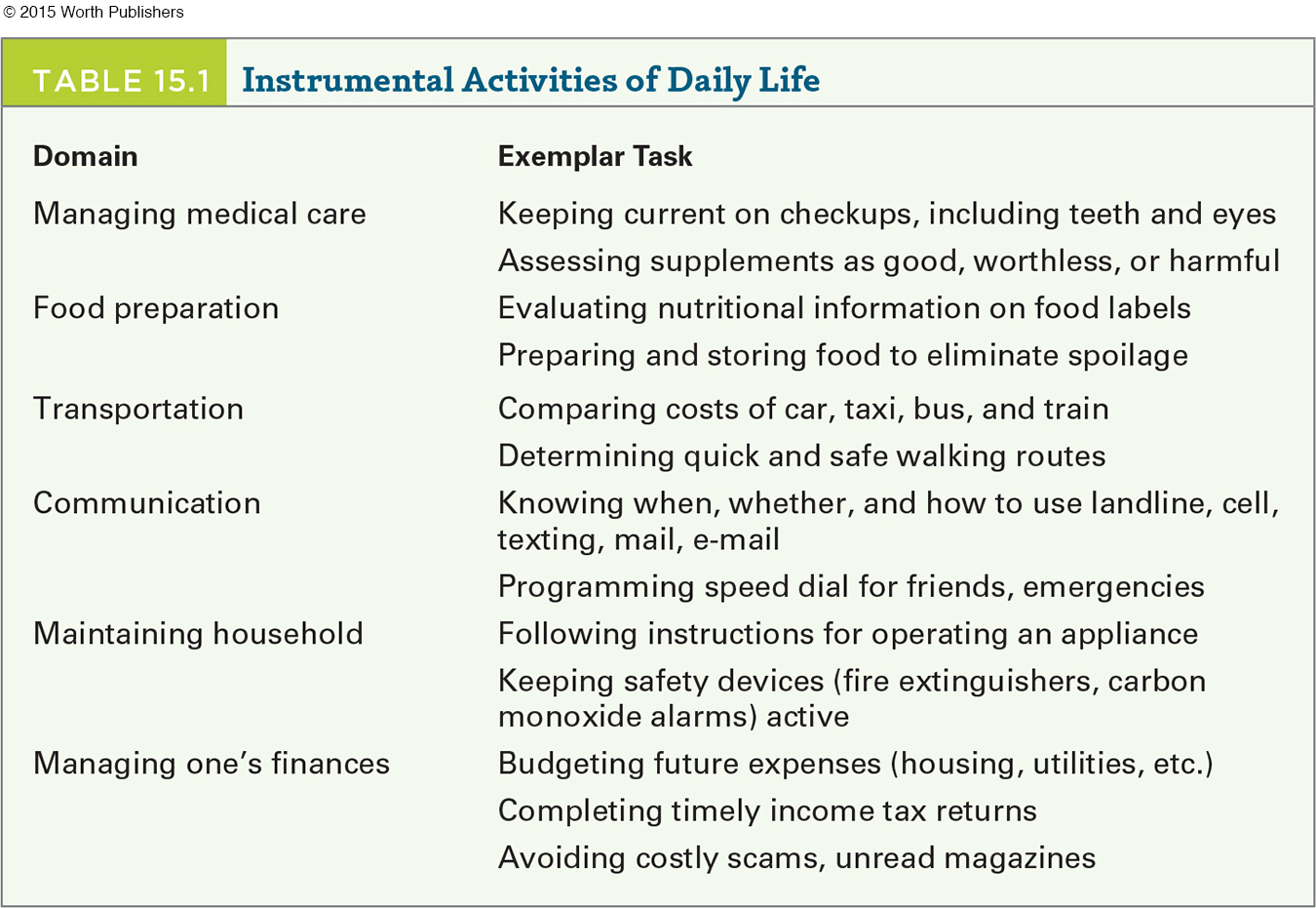

Equally important may be the instrumental activities of daily life (IADLs), which require intellectual competence and forethought. Indeed, difficulty with IADLs often precedes problems with ADLs since planning and problem solving help frail elders maintain self-

The five ADL’s are fairly standard: People everywhere who cannot do them need help. However, that does not mean they are dependent forever; ADLs are dynamic: Most of the elderly who have difficulty with one of more ADL are able to recover (Ciol et al., 2014).

Recovery is especially likely if someone teaches them how to, for instance, put on shoes without bending down, or get out of bed without risking a fall. Physical therapists may be crucial here, not only in explaining ways to accomplish self-

IADLs vary from culture to culture, although again targeted help may be beneficial. In developed nations, IADLs may include understanding the labels on medicine bottles, improving nutrition of the daily diet, filing income tax, using modern appliances, making and keeping doctor appointments (see Table 15.1). Even within developed nations, professionals vary in their lists of IADLs (Chan et al., 2012).

562

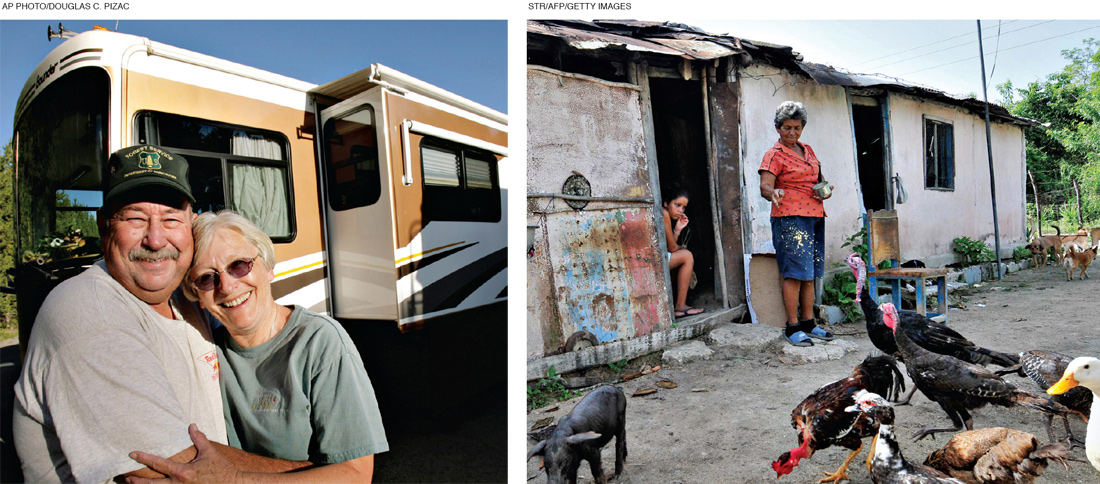

In rural areas of developing nations, feeding the chickens, cultivating the garden, mending clothes, getting water from the well, and making dinner might be IADLs. As with ADLs, some assistance might be needed, but taking over the task (“you can’t do it, you’re too old”) may precipitate frailty.

Caregiving may be a crucial IADL. Some caregiving requires quite advanced competence, such as caring for a toddler. Some does not, as in caring for a pet or a plant. For many of the elderly, caregiving maintains dignity as well and cognition—

Whose Responsibility?

There are marked cultural differences in care for the frail elderly. Many African and Asian cultures hold sons responsible for the care of their parents. Some men and their wives take elders into their homes, providing meals, medical care, and conversation.

However, as already mentioned, this is increasingly difficult in modern times in every nation. The governments of China and India have mandated that children care for their parents, a mandate that itself suggests that many parents need care they are not getting.

The problem is that demographics have changed, which impacts filial responsibility. Some people still romanticize elder care, believing that frail older adults should live with their caregiving children. That assumption worked when the demographic pyramid meant that each surviving elder had many descendants, but it may overburden beanpole families.

Some middle-

563

Fortunately, as already mentioned, most elderly people care for themselves. However, typically, at least one of the oldest generation of an average couple is frail and alone, and others need help with money management, or throwing away old food, or the like. If a middle-

Preventing Frailty

The ideal is to prevent frailty and to compress morbidity, as described in Chapter 14. Some elders are healthy and self-

Prevention of frailty depends on everyone considering that disability is dynamic, not static, with self-

MOBILITY Muscles weaken with age, a condition called sarcopenia. In fact, muscle mass at age 90 is only half of what it was at age 30, with much of that loss occurring in late adulthood (McLean & Kiel, 2015).

Bones and balance weaken as well. Thus, elderly people are more likely to fall than younger people are, and they are more likely to break a bone when doing so.

As already mentioned, osteoporosis (weak bones) is a common problem, and broken bones—

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Leave the Bedroom

Medical intervention has remedied much of one cause of frailty (osteoporosis) in that prescription drugs and vitamin D strengthen bones. In addition, for many people hip or knee replacement restores mobility (Jenkins et al., 2013). Both require surgery, pain, and rehabilitation exercises, and require an active choice. Unfortunately, sarcopenia and immobility may be accepted, not remediated. Fear of falling may increase the risk.

For some elders, aging in place might mean staying in a home with steep stairs and a kitchen and bathroom far from the bedroom. Then an overly solicitous caregiver might bring meals, put a portable toilet in their room, and buy a remote control for their large bedroom TV. The community may contribute to the fear of going outside, if sidewalks are lacking and if the TV news highlights violent crime. Note that everyone contributes to frailty in this example.

To prevent frailty, the individual, the family, and the community could change. The person could exercise daily, walking with family members on pathways built to be safe and pleasant. A physical therapist—

Extensive research has found again and again that lack of exercise leads to lower quality of life, increasing both ADLs and IADLs. On the other hand, exercise improves life and health in the elderly who live in the community (Motl & McAuley, 2010) as well as those already frail in nursing homes (Weening-

For instance, one study randomly assigned nursing-

In general, both attitude change and exercise carefully tailored to the individual is beneficial. However, translating that research into action—

564

Mental Capacity

Problems with IADLs may be worse than problems with ADLs. Here again, the family and community may be crucial.

The social support networks that prevent physical decline also prevent mental decline (Boss et al., 2015). With many types of failing physical and mental health, delay, moderation, and sometimes prevention are possible. Often older individuals, and the people who love them, need to put in place all the safeguards and develop all the habits that will prevent frailty.

A CASE TO STUDY

Family Encouraging Confusion

Consider this case, noting what the family did and did not do.

[A] 70-

. . . . He had a lapse of more than five years without proper control of his medical problems [hypertension and diabetes] because of difficulty gaining access to medical care. . . .

Based on the medical history, a cognitive exam . . . and a medical evaluation in which magnetic resonance imaging of the brain . . . the diagnosis of moderate Alzheimer’s disease was made. Treatment with ChEI [cholinesterase inhibitors] was started . . . His family noted that his apathy improved and that he was feeling more connected with the environment.

[Griffith & Lopez, 2009, p. 39]

Both the community (those five years without treatment for hypertension and diabetes) and the family (making excuses, protecting him) contributed to major neurocognitive disorder that could have been delayed, if not prevented altogether.

Often with IADLs, the elderly person him-

Caring for the Frail Elderly

Prevention is best, but not always sufficient. Some problems, such as major neurocognitive disorder or severe heart failure, can be postponed or slowed, but not eliminated. Caregivers themselves are usually elderly, and they often have poor health, limited strength, and impaired immune systems (Lovell & Wetherell, 2011). Thus an aging parent who cares for the other parent is especially likely to need help.

565

Caregiving is especially difficult when a person has failing IADLs, because they do not realize what help they need. If people have trouble with an ADL, they know that they cannot walk, for instance. But if a person has trouble with an IADL, they might insist that they can submit tax forms perfectly well and may become angry if the IRS fines them.

After listing the problems and frustrations of caring for someone who is mentally incapacitated but physically strong, the authors of one overview note:

The effects of these stressors on family caregivers can be catastrophic. Family caregiving has been associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety as well as higher use of psychoactive medications, poorer self-

[Gitlin et al., 2003, pp. 361–

Remember variability, however. Some caregivers feel they are repaying past caregiving, and sometimes every other family member or friend, including the care receiver, expresses appreciation. That relieves resentment and makes caregiving easier (I-

The designated caregiver of a frail elderly person is chosen less for logical reasons (e.g., the relative with the most patience, time, and skill) than for cultural ones. Currently in the United States, the usual caregiver is the spouse (the wife twice as often as the husband), who often has no prior experience caring for a frail elder.

Grown children may assume that another sibling has fewer responsibilities, or lives closest, and thus should be the caregiver. As you might imagine, resentment is common, particularly in daughters with more education (I-

Not only do family assumptions vary; nations, cultures, and ethnic groups vary as well. In northern European nations, most elder care is provided through a social safety net of senior day-

In some cultures, an older person who is dying is taken to a hospital; in others, such intervention is seen as interference with the natural order. In the United States, African Americans who enter nursing homes are more likely than European Americans to suffer from major intellectual deficits, perhaps because elderly African Americans with merely physical frailties (ADLs not IADLs) are more often cared for at home. Only when care becomes emotionally crushing are alternatives to home care considered.

Even in ideal circumstances, family members disagree about appropriate nutrition, medical help, and dependence of an older relative. One family member may insist that an elderly person never enter a nursing home, and that insistence may create family conflict.

Public agencies rarely intervene unless a crisis arises. This troubles developmentalists, who study “change over time.” From a life-

566

If elders need extensive care, ideally skilled people provide it, teaching family members to help. But many elders are terrified of nursing homes and suspicious of strangers; many informal caregivers do not ask for help, and instead experience depression, poor health, and isolation—

integrated care

Cooperative actions by professionals, friends, family members, and the care receiver to achieve optimal caregiving.

The ideal is integrated care, in which professionals and family members cooperate to provide good individualized care, whether at a long-

Integrated care does not erase the burden of caregiving, but it helps. In one study, a year after a professional helped plan and coordinate care, family caregivers improved in their overall attitude and quality of life. Although the total time spent on caregiving was not reduced by integrated care, the tasks performed changed, with more time on household tasks (e.g., meal preparation and cleanup) and less on direct care (Janse et al., 2014). Emotional support—

The idea that a frail person is cared for either exclusively by family or exclusively in a nursing home is not only wrong, it is destructive of health and well-

ELDER ABUSE When caregiving results in resentment and social isolation, the risk of depression, sickness, and abuse (of either the frail person or the caregiver) escalates (G. Smith et al., 2011; Johannesen & LoGiudice, 2013). Abuse is likely if:

the caregiver suffers from emotional problems or substance abuse

the care receiver is frail, confused, and demanding

the care location is isolated, where visitors are few

Ironically, although relatives are less prepared to cope with difficult patients than professionals are, they often provide round-

Often professionals begin their care too late. Most doctors treat a patient in a medical crisis (a fall, heart attack, and so on) but not before. Legal authorities intervene only after repeated and blatant abuse. Preventive care could have forestalled both kinds of problems.

As a result, some caregivers overmedicate, lock doors, and use physical restraints, all of which may be abusive. That may lead to inadequate feeding, medical neglect, or rough treatment. Obvious abuse is less likely in nursing homes and hospitals, not only because laws forbid it but also because workers are not alone, nor expected to work 24/7.

Of course, adequate staffing and supervision are essential in such places as well: Abuse can occur anywhere. One kind of abuse is particularly likely in nursing homes when staff supervision is inadequate, specifically abuse by other residents. Typically the abuser is a man with a history of aggression who is suffering from major neurocognitive disorder; obviously such men need to be prevented from harming others (Ferrah et al., 2015).

567

Extensive public and personal safety nets are needed. Most social workers and medical professionals are suspicious if an elder is unexpectedly quiet, or losing weight, or injured. They are currently “mandated reporters,” which means they must alert the authorities if they believe abuse is occurring.

Not all elder abuse is physical. It may instead be financial, yet bankers, lawyers, and investment advisors are not trained to recognize it or obligated to respond and notify anyone (Jackson & Hafemeister, 2011).

A major problem is awareness: Professionals and relatives alike hesitate to spot and then question a family caregiver who spends the Social Security check, disrespects the elder, or does not comply with the elder’s demands. At what point is this abuse? Typically, abuse begins gradually and continues for years, unnoticed. Political and legal definitions and remedies are not clear-

The U.S. incidence of elder abuse is estimated at less than 3 percent of the population over age 65 (Bond & Butler, 2013). That percentage seems small, but remember that the vast majority of older people are vital and independent, not vulnerable to abuse. Those 3 percent (about a million individuals per year) are almost always the most vulnerable and impaired.

Accurate incidence data and intervention are complicated by definitions: If an telder feels abused but a caregiver disagrees, who is right? Abused elders are often depressed, ill, and suffering from neurocognitive disorders. Does that prove abuse or absolve abusers (Dong et al., 2011)?

Sometimes caregivers become victims, attacked by a confused elderly person. As with other forms of abuse, the dependency of the victim makes prosecution difficult, especially when secrecy, suspicion, and family pride keep outsiders away. Social isolation makes abuse possible; fear of professionals makes it worse.

Video: Nursing Homes

LONG-

Fortunately, outright abuse in such institutions is rare. Laws forbid the use of physical restraints except temporarily in specific, extraordinary circumstances. Some nursing homes provide individualized, humane care, allowing residents to decide what to eat, where to walk, whether to have a pet. In the United States, nursing homes are frequently visited by government inspectors to “stop dreadful things from happening” (Baker, 2007).

In North America, good nursing-

Good care allows independence, individual choice, and privacy. As with day care for young children, continuity of care is crucial: An institution with a high rate of staff turnover is to be avoided. At every age, establishing relationships with other people is crucial: If the residents feel that their caregivers are the same year after year, that improves well-

The training and the workload of the staff, especially of the aides who provide frequent, personal care, are crucial: Such simple tasks as helping a frail person out of bed can be done clumsily, painfully, or skillfully. Skill, experience, and patience are all critical, and all are possible with a sufficient number of well-

568

Many nursing homes now have dedicated areas and accommodation for people with Alzheimer’s disease or other neurocognitive disorders. Among the special characteristics are memory boxes, in addition to names on the doors of the rooms. A memory box is open to view and displays photographs and other mementos so that the person knows which room is his or hers.

Many people with major neurocognitive disorder do not understand why they need care and often resist it. Nursing homes may treat such resistance with psychoactive drugs (Kleijer et al., 2014), but other tactics may be better at reducing anxiety (Konno et al., 2014). For instance, music, friendly dogs, and favorite foods can be appreciated by someone whose memory is so impaired that reading and conversing are impossible.

Quality care is much more labor-

In the United States, the trend over the past 20 years has been toward a lower proportion of those over age 60 residing in nursing homes, and those few are usually over 80 years old, frail and confused, with several medical problems (Moore et al., 2012).

Another trend is toward smaller nursing homes with more individualized care, where nurses and aides work closely together. Some homes are called Eden Alternative or Green, named after exemplars that stress individual autonomy (Sharkey et al., 2011).

Although more than 90 percent of elders are independent and live in the community at any given moment, many of them will someday need nursing-

ALTERNATIVE CARE An ageist stereotype is that older people are either completely capable of self-

Once that is understood, a range of options can be envisioned. Remember the study cited in Chapter 14 that found that major neurocognitive disorder is less common in England than it used to be? That study also found that the percentage of people with neurocognitive disorders in nursing homes has risen, from 56 percent in 1991 to 65 percent in 2011, primarily because of a rise in the number of oldest-

569

This means that more British elderly who need help with ADLs are now in the community. This is good news for the elderly, for developmentalists, and for the community, because aging in place, assisted living, and other options are less costly and more individualized than institutions.

The number of assisted-

The “assisted” aspects vary, often one daily communal meal, special transportation and activities, household cleaning, and medical assistance, such as supervision of pill taking and monitoring of blood pressure or diabetes. Usually, a nurse, doctor, and ambulance are available if needed. In the United States, many of these assistances involve additional expenses.

Assisted-

Another form of elder care is sometimes called village care. Although not really a village, it is so named because of the African proverb, “It takes a whole village to raise a child.” In village care, elderly people who live near each other pool their resources, staying in their homes but also getting special assistance when they need it. Village care communities require that the elderly contribute financially and that they be relatively competent, so village care is not suited for everyone. However, for some it is ideal (Scharlach et al., 2012).

Overall, as with many other aspects of aging, the emphasis in living arrangements is on selective optimization with compensation. Elders need settings that allow them to be safe, social, respected, and as independent as possible. Housing solutions vary depending not only on ADLs and IADLs but also the elder’s personality and social network of family and friends. One expert explains: “There is no one-

570

We close with an example of family care and nursing-

Fortunately, this nursing home did not assume that decline is always a sign of “final failing” (Rob’s phrase). The doctors discovered that her pacemaker was not working properly. Rob tells what happened next:

We were very concerned to have her undergo surgery at her age, but we finally agreed. . . . Soon she was back to being herself, a strong, spirited, energetic, independent woman. It was the pacemaker that was wearing out, not Great-

[quoted in Adler, 1995, p. 242]

This story contains a lesson repeated throughout this book. Whenever a toddler does not talk, a preschooler grabs a toy, a teenager gets drunk, an emerging adult takes risks, an adult seeks divorce, or an older person becomes frail, it is easy to conclude that this is normal. Indeed, each of these possible problems is common at the ages mentioned and may be appropriate and acceptable for some individuals.

But none should simply be accepted without question. Each should also alert others to encourage talking, sharing, moderation, caution, communication, or self-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.24

1. What factors make an older person frail?

Frail elderly are people over age 65, and often over age 85, who are physically infirm, very ill, or cognitively disabled.

Question 15.25

2. What are the basic differences between ADLs and IADLs?

ADLs (activities of daily life) include eating, bathing, toileting, dressing, and moving from a bed to a chair. IADLs (instrumental activities of daily life) include actions such as paying bills or driving a car, things that are important to independent living and that require some intellectual competence and forethought.

Question 15.26

3. Why might IADLs be more important than ADLs in deciding how much care a person needs?

IADLs are actions important to independent living—

Question 15.27

4. What are the signs of frailty?

Frailty begins with an overall loss of energy and strength; it is systemic, often accompanied by weight loss and exhaustion.

Question 15.28

5. What can be done to increase mobility in the aged?

One example is that physical therapists can teach specific exercises and movements to improve mobility.

Question 15.29

6. How is cognitive decline related to prevention of frailty?

The social support networks that prevent physical decline can also aid in preventing mental decline.

Question 15.30

7. What three factors increase the likelihood of elder abuse?

Elder abuse is most common if 1) the caregiver suffers from emotional problems or substance abuse; 2) the care receiver is frail, confused, and demanding; and 3) the care location is isolated, where visitors are few. In addition, relatives who have had little training are often required to provide substantial and nearly constant care without help or supervision; a lack of support, training, and respite are problems.

Question 15.31

8. What are the advantages and disadvantages of assisted living for the elderly?

Advantages: Assisted-

Question 15.32

9. When is a nursing home a good solution for the problems of the frail elderly?

It is a good solution for some elders, usually over 80 years old, frail and confused, with several medical problems. Some need such care for more than a year, and a very few stay for 10 years or more.

Question 15.33

10. What factors distinguish a good nursing home from a bad one?

Good care allows independence, individual choice, and privacy. Continuity of care is crucial: An institution with a high rate of staff turnover is to be avoided. At every age, establishing relationships with other people is also crucial: If the residents feel that their caregivers are the same year after year, that improves well-