Families and Children

No one doubts that genes affect personality as well as ability, that peers are vital, and that schools and cultures influence what, and how much, children learn. Some experts have gone further, suggesting that genes, peers, and communities are so influential that parenting has little impact—

Shared and Nonshared Environments

Question 8.9

OBSERVATION QUIZ

The 12-

Their appearance and clothes are very similar. However, their relationship to their mother may differ.

Many studies find that children are much less affected by shared environment (influences that arise from being in the same environment, such as two siblings living in one home, raised by their parents) than by nonshared environment (e.g., the experiences in the school or neighborhood that differ between one child and another).

Almost all personality traits and intellectual characteristics can be traced to the combined influence of genes and nonshared environments, with little left over for the shared influence of being raised together. Even psychopathology, happiness, and sexual orientation (Burt, 2009; Långström et al., 2010; Bartels et al., 2013) arise primarily from genes and nonshared environment.

Since research finds that shared environment has little impact, could it be that parents are merely caretakers? Mothers and fathers need to provide basics (food, shelter) and are harmful when abusive, but might their household restrictions, routines, and responses be irrelevant? If a child becomes a murderer or a hero, could that be genetic and nonshared? Perhaps parents deserve neither blame nor credit!

289

Recent findings, however, reassert parent power. The analysis of shared and nonshared influences was correct, but the conclusion was based on a false assumption. Siblings raised together do not share the same environment.

For example, if relocation, divorce, unemployment, or a new job occurs in a family, the impact on each child depends on his or her age, genes, and gender. Moving to another town upsets a school-

The variations above do not apply for all siblings: Differential susceptibility means that one child is more affected, for better or worse, than another (Pluess & Belsky, 2010). When siblings are raised together, all experiencing the same dysfunctional family, then their genes, age, and gender may lead one child to become antisocial, another to be pathologically anxious, and a third to be resilient, capable, and strong (Beauchaine et al., 2009).

Further, parents do not treat each of their children the same, in part because birth order and gender differ. It is mistaken to assume that family experiences are the same for the eldest and the youngest. Even identical twins might have different family experiences, as in the following.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

“I Always Dressed One in Blue Stuff . . .”

To separate the effects of genes and environment, many researchers have studied twins. As you remember from Chapter 2, some twins are dizygotic, with only half of their genes in common, and some are monozygotic, genetically identical.

If monozygotic twins had the same trait as their twin but dizygotic twins did not share that trait, researchers assumed that genes were the reason. However, if monozygotic twins were no more similar than dizygotic twins on a trait, then nonshared environment (i.e., non-

Comparing monozygotic and dizygotic twins continues to be a useful research strategy. However, conclusions are now tempered by another finding: Siblings raised in the same households do not necessarily share the same home environment. A seminal study occurred with twins in England.

An expert team of scientists compared 1,000 sets of monozygotic twins reared by their biological parents (Caspi et al., 2004). Of course, the pairs were identical in genes, sex, and age. The researchers asked the mothers to describe each twin. Descriptions ranged from very positive (“my ray of sunshine”) to very negative (“I wish I had never had her. . . . She’s a cow, I hate her”) (quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 153). Many mothers noted personality differences between their twins. For example, one mother said:

Susan can be very sweet . . . She loves babies . . . she can be insecure . . . she flutters and dances around. . . . There’s not much between her ears. . . . She’s exceptionally vain, more so than Ann. Ann loves any game involving a ball, very sporty, climbs trees, very much a tomboy. One is a serious tomboy and one’s a serious girlie girl. Even when they were babies I always dressed one in blue stuff and one in pink stuff.

[quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 156]

Some mothers rejected one twin and favored the other:

He was in the hospital and everyone was all “poor Jeff, poor Jeff” and I started thinking, “Well, what about me? I’m the one’s just had twins, I’m the one’s going through this, he’s a seven-

[quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 156]

This same mother later blamed Jeff for favoring his father: “Jeff would do everything for Don but he wouldn’t for me, and no matter what I did for either of them [Don or Jeff] it wouldn’t be right” (p. 157). She said Mike was much more lovable.

The researchers measured each twin’s personality at age 5 (assessing, among other things, antisocial behavior reported by teachers) and again two years later. They found that if a mother was more negative toward one of her twins, that twin became more antisocial, more likely to fight, steal, and hurt others at age 7 than at age 5, unlike the favored twin.

These researchers acknowledge that many other nonshared factors—

Family Structure and Family Function

290

family structure

The legal and genetic relationships among relatives living in the same home. Possible structures include nuclear family, extended family, stepfamily, single-

Family structure refers to the legal and genetic connections among related people. Legal connections are via marriage, years of cohabitation, or adoption. Genetic connections are from parent to child, or between siblings, cousins, grandparents and grandchildren, and so on.

family function

The way a family works to meet the needs of its members. Children need families to provide basic material necessities, to encourage learning, to help them develop self-

Family function refers to how the people in a family work together to care for the family members. Some families function well, others are dysfunctional.

Function is more important than structure, although harder to measure. Some family functions are needed by everyone at every age, such as love and encouragement. Beyond that, what people need from their families differs depending on how old they are: Infants need responsive caregiving, teenagers need guidance, young adults need freedom, the aged need respect.

THE NEEDS OF CHILDREN IN MIDDLE CHILDHOOD What do children need from their families during middle childhood? Ideally, five things:

Physical necessities. Although 6-

to 11- year- olds eat, dress, and go to sleep without help, families provide basic needs, such as for food, clothing, and shelter. Learning. Middle childhood covers the prime learning years: Families support, encourage, and guide education.

Self-

respect. Because children from age 6 to 11 become self- critical and socially aware, families provide opportunities for success (in academics, sports, the arts, and so on). Peer relationships. Families choose schools and neighborhoods with friendly children and then arrange play dates, group activities, overnight trips, and so on.

Harmony and stability. Families provide protective, predictable routines within a home that is a safe, peaceful haven.

The final item on the list above is especially crucial in middle childhood: Children cherish safety and stability; they do not like change (Turner et al., 2012). Ironically, many parents move from one neighborhood or school to another during these years. Children who move frequently may be harmed, academically and psychologically (Cutuli et al., 2013).

291

The problems arising from instability are evident for U.S. children in military families. Enlisted parents tend to have higher incomes, better health care, and more education than do civilians from the same backgrounds. But they have one major disadvantage: They move. In reviewing earlier research, a scientist reports “military parents are continually leaving, returning, leaving again . . . School work suffers, more for boys than for girls, . . . reports of depression and behavioral problems go up when a parent is deployed” (Hall, 2008, p. 52).

About half the military personnel who are on active duty have children, and many of their children learn to cope with the stresses they experience (Russo & Fallon, 2014). To help them, the U.S. military has instituted special programs. Caregivers are encouraged to avoid changes in the child’s life: no new homes, new rules, or new schools (Lester et al., 2011).

nuclear family

A family that consists of a father, a mother, and their biological children under age 18.

DIVERSE STRUCTURES Family diversity should be acknowledged but not exaggerated. More than two-

| Two- |

|

|

|

| Single- |

|

| One- |

|

|

|

| More Than Two Adults (10%) [Also listed as two- |

|

|

|

| *Less than 1 percent of U.S. children live without any caregiving adult; they are not included in this table. | |

| The percentages on this table are estimates, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau. The category “extended family” in this table is higher than most published statistics, since some families do not tell official authorities about relatives living with them. | |

292

single-

A family that consists of only one parent and his or her children.

Single-

Rates of various structures change depending on the age of the child: More than half of all contemporary U.S. children will live in a single-

extended family

A family of three or more generations living in one household.

Extended families consist of relatives residing with parents and children. Usually the additional persons are grandparents; sometimes they are uncles, aunts, or cousins of the child.

The crucial distinction between types of families is based on who lives together in the same household, a distinction that does not necessarily reflect the experience of the child. Many so-

polygamous family

A family consisting of one man, more than one wife, and their children.

In many nations, polygamous families (one husband with two or more wives) are an acceptable family structure. Family function may suffer in that structure, because often income per child is reduced, and education, especially for the girls, is limited (Omariba & Boyle, 2007). On the other hand, many argue that polygamy is preferable to divorce and remarriage, since most fathers who left one wife and married another are less involved with children from their first marriage than they would have been if they were the head of a polygamous family (Calder & Beaman, 2014).

Related to that is the role of stepsiblings, who are part of many family structures. Living in a family with stepsiblings, even for children who are the biological offspring of the current parents, affects family function. Children in these “complex” family structures are less likely to do well in school and in life (Brown et al., 2015).

DIVORCE Scientists try to provide analysis and insight based on empirical data (of course), but the task goes far beyond reporting facts. Regarding divorce, thousands of studies and several opposing opinions need to be considered, analyzed, and combined—

Among the facts that need analysis are these:

The United States leads the world in the rates of marriage, divorce, and remarriage, with almost half of all marriages ending in divorce.

Single parents, cohabiting parents, and stepparents sometimes provide good care, but children tend to do best in nuclear families with married parents.

Divorce often impairs children’s academic achievement and psychosocial development for years, even decades.

Each of these is troubling. Why does this occur? The problem, Cherlin (2009) contends, is that U.S. culture is conflicted: Marriage is idolized, but so is personal freedom. As a result, many people assert their independence by marrying without consulting their parents or community. If such a love-

However, Cherlin argues, because marriage remains the ideal, divorced adults blame their former mate or their own poor decisions, not the institution or the society. Consequently, they seek another marriage, which may lead to another divorce. (Divorced people are more likely to remarry than single people their age are to marry). Repeated transitions allow personal freedom for the adults but harm the children.

293

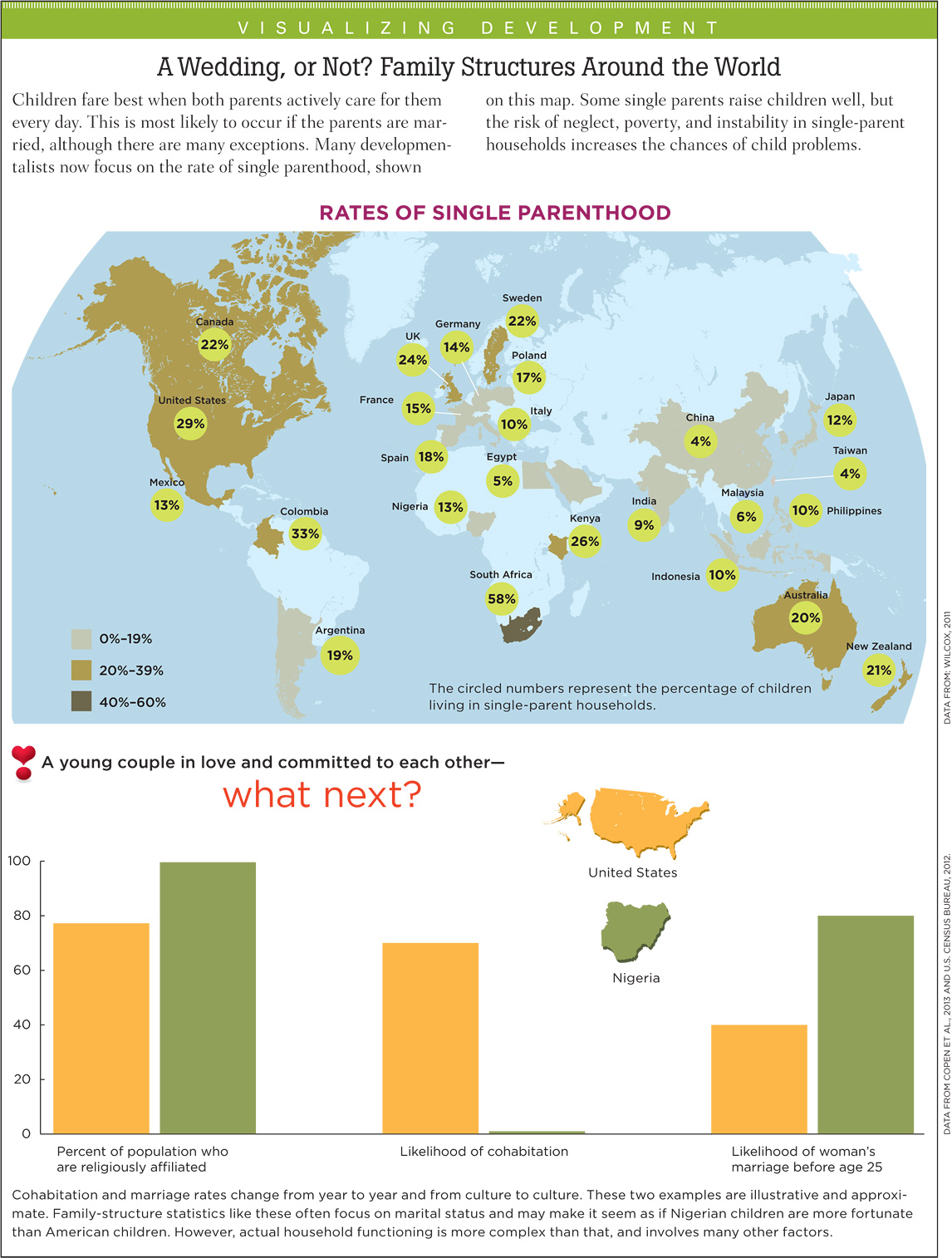

Check out the Data Connections activity Family Structure in the United States and Around the World.

This leads to a related insight. Cherlin suggests that the main reason children are harmed by divorce—

For example, divorces typically include many disruptions: in residence, in school, in family members, and—

Scholars now describe divorce as a process, with transitions and conflicts before and after the formal event (H. S. Kim, 2011; Putnam, 2011). This process entails repeated changes and ongoing hassles for the children. The child’s ability to cope is particularly compromised if the child is experiencing a developmental transition, such as entering first grade or beginning puberty.

Nonetheless, some researchers believe that divorce may be better for the child than an ongoing, destructive family. As one scientist who studied divorced families for decades wrote:

Although divorce leads to an increase in stressful life events, such as poverty, psychological and health problems in parents, and inept parenting, it also may be associated with escape from conflict, the building of new more harmonious fulfilling relationships, and the opportunity for personal growth and individuation.

[Hetherington, 2006, p. 204]

Not every parent should marry, not every marriage should continue, and not every divorce is harmful. However, every child needs parents to fulfill all five needs of school-

Connecting Structure and Function

As obvious with divorce, the fact that family function is more important for children than family structure does not make structure irrelevant. Structure influences function and vice versa. The crucial question is whether the structure makes it more or less likely that the five family functions mentioned earlier (physical necessities, learning, self-

NUCLEAR FAMILIES On average, nuclear families function best; children in the nuclear structure tend to achieve better in school with fewer psychological problems. A scholar who summarized dozens of studies concludes: “Children living with two biological married parents experience better educational, social, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes than do other children” (Brown, 2010, p. 1062).

Do the proven benefits of nuclear families mean that everyone should marry before they have a child, and then stay married? Not necessarily. Some benefits are correlates, not causes.

Education, earning potential, and emotional maturity all correlate with getting married and staying married. For example, if women having their first baby are highly educated, they are usually married (78 percent) at conception; but if they are poorly educated, they are rarely married (only 11 percent) (Gibson-

Brides and grooms tend to have personal assets before marriage and parenthood, and they bring those assets to their new family. This means that the correlation between child success and married parents occurs partly because of who marries, not because of the wedding. Indeed, for some very low-

294

Income correlates with family structure. Usually, married couples live apart from their parents if everyone can afford it. That means that, at least in the United States, an extended family suggests that someone is financially dependent, not that a child has many loving adults at home.

These two factors—

Evidence for the benefits of the parental alliance comes from Russia, where recent economic upheaval reduced a man’s average life span from age 64 in 1985 to 59 in 2000. Most at risk for an early death are single men, who have high rates of depression and alcoholism. If a Russian man lives with his wife and children, he tends to take better care of himself and his children (Ashwin & Isupova, 2014).

Shared parenting not only decreases rates of depression, in Russia and elsewhere, but it also decreases child maltreatment. Further, having two parents at home makes it more likely that someone will read to the child, check homework, invite friends over, buy new clothes, and save for college. Of course, having two married parents does not guarantee anything. One of my students wrote:

My mother externalized her feelings with outbursts of rage, lashing out and breaking things, while my father internalized his feelings by withdrawing, being silent and looking the other way. One could say I was being raised by bipolar parents. Growing up, I would describe my mom as the Tasmanian devil and my father as the ostrich, with his head in the sand. . . . My mother disciplined with corporal punishment as well as with psychological control, while my father was permissive. What a pair.

[C., 2013]

Question 8.10

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What is unusual about this family?

Both parents are women. The evidence shows that same-

295

This student never experienced a well-

One consequence: When children reach “the age of majority” (usually 18) and fathers are no longer legally responsible, many divorced or unmarried fathers stop child support. Unfortunately, most emerging adults need financial support to attend college or live independently, so a long-

This benefit for children in nuclear families is more than financial. When remarried adults have incomes comparable to that of nuclear parents, they contribute less, on average, to children who live with them (Turley & Desmond, 2011). Fathers typically spend less time caring for stepchildren than biological children (Kalil et al., 2014b). As adults, stepchildren tend to live farther from either their biological father or their stepfather than other adult children do (Seltzer et al., 2013). Thus, because divorce weakens the parental alliance in childhood, nuclear families tend to be more cohesive lifelong.

OTHER TWO-

No structure is guaranteed to function well, but particular circumstances for all three family types—

296

Compared with other two-

Not only is stability more difficult for stepfamilies; harmony is more difficult as well (Martin-

Children who gain a stepparent may be angry or sad, so they often act out (e.g., fight with friends, fail in school, disobey adults). That causes arguments for their newly married parents, who may have opposite strategies for managing misbehavior. Further, disputes between half-

Finally, the grandparent family is often idealized, but reality is much more complex. If a household has grandparents and parents, the grandparents may be care-

Sometimes one or two grandparents provide full-

SINGLE-

Rates of single parenthood and single grandparenthood are far higher among African Americans than other ethnic groups. This makes children from single-

A CASE TO STUDY

How Hard Is It to Be a Kid?

Neesha’s fourth-

The counselor spoke to Neesha’s mother, Tanya, a depressed single parent who was worried about paying rent on the tiny apartment where she had moved when Neesha’s father left three years earlier. He lived with his girlfriend, now with a new baby. Tanya said she had no problems with Neesha, who was “more like a little mother than a kid,” unlike her 15-

297

Tyrone was recently beaten up badly as part of a gang initiation, a group he considered “like a family.” He was currently in juvenile detention after being arrested for stealing bicycle parts. Note the nonshared environment here: Although the siblings grew up together, 12-

The school counselor spoke with Neesha.

Neesha volunteered that she also worried a lot about things and that sometimes when she worries she has a hard time falling asleep. . . . she got in trouble for being late so many times, but it was hard to wake up. Her mom was sleeping late because she was working more nights cleaning offices. . . . Neesha said she got so far behind that she just gave up. She was also having problems with the other girls in the class, who were starting to tease her about sleeping in class and not doing her work. She said they called her names like “Sleepy” and “Dummy.” She said that at first it made her very sad, and then it made her very mad. That’s when she started to hit them to make them stop.

[Wilmshurst, 2011, pp. 152–

Neesha is coping with poverty, a depressed mother, an absent father, a delinquent brother, and classmate bullying. She seems resilient—

The school principal received a call from Neesha’s mother, who asked that her daughter not be sent home from school because she was going to kill herself. As she spoke on the telephone, she explained that she was holding a loaded gun in her hand and she had to do it, because she was not going to make this month’s rent. She could not take it any longer, but she did not want Neesha to come home and find her dead. . . . While the guidance counselor continued to keep the mother talking, the school contacted the police, who apprehended mom while she was talking on her cell phone. . . . The loaded gun was on her lap. . . . [The] mother . . . was taken to the local psychiatric facility.

[Wilmshurst, 2011, pp. 154–

Whether Neesha will be able to cope with her problems depends on whether she can find support beyond her family. Perhaps the school counselor will help:

When asked if she would like to meet with the school psychologist once in a while, just to talk about her worries, Neesha said she would like that very much. After she left the office, she turned and thanked the psychologist for working with her, and added, “You know, sometimes it’s hard being a kid.”

[Wilmshurst, 2011, p. 154]

Family structure encourages or undercuts healthy function, but many parents and communities overcome structural problems to support their children. Contrary to the averages, thousands of single-

Culture is always influential. In contrast to data from the United States, a study in the slums of Mumbai, India, found rates of psychological disorders among school-

On the other hand, another study found that college students in India who injured themselves (e.g., cutting) were more often from extended families than nuclear ones (Kharsati & Bhola, 2014). One explanation is that these two studies had different populations: College students tend to be from wealthier families, unlike the children in Mumbai.

THINK CRITICALLY: Can you describe a situation in which having a single parent would be better for a child than having two parents?

Although these studies from India differed regarding extended families, both studies found that children from single-

Family Trouble

Two factors impair family function in every structure, ethnic group, and nation: low income and high conflict. Many families experience both: Financial stress increases conflict and vice versa.

298

299

WEALTH AND POVERTY Family income correlates with both function and structure. Marriage rates fall in times of recession, and divorce correlates with unemployment. Low SES increases the rate of many problems; “risk factors . . . pile up in the lives of some children, particularly among the most disadvantaged” (Masten, 2014, p. 95).

Several scholars have developed the family-

If economic hardship is ongoing, if uncertainty about the future is high, if education is low—

More income correlates with better family functioning. For example, children in single-

Surprisingly, reaction to wealth may also cause difficulty. Children in high-

CONFLICT Every researcher agrees that family conflict harms children, especially when adults fight about child rearing. Such fights are more common in stepfamilies, divorced families, and extended families, but nuclear families are not immune. Children suffer if they witness fights between their parents. Fights between siblings can be harmful, too (Turner et al., 2012).

Some researchers hypothesize that children are emotionally troubled in families with feuding parents because of their genes, not because of what they see. The hypothesis is that the parents’ genes lead to marital problems. If that is true, and if children inherit those same genes, then genes, not experiences, trouble the children whose parents fight.

This hypothesis was tested in a longitudinal study of 867 adult twins (388 monozygotic pairs and 479 dizygotic pairs), all married with an adolescent child. Each adolescent was compared to his or her cousin, the child of one parent’s twin (Schermerhorn et al., 2011). Thus, this study had data from 5,202 individuals—

The researchers found that, although genes had some influence, witnessing conflict was crucial, causing externalizing problems in boys and internalizing problems in girls. In this study, quiet disagreements did little harm, but open conflict (such as yelling when children could hear) and divorce did (Schermerhorn et al., 2011).

300

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 8.11

1. Why do siblings raised together not share the exact same environment?

The age of each child at the time of significant events, such as parental divorce, can cause different effects on each child. Each child has a different relationship with each parent, so that even though the children are raised in the same household with the same parents, the children’s experiences may vary.

Question 8.12

2. What is the difference between family structure and family function?

Family structure refers to the legal and genetic connections among people living in the same household, e.g., single-

Question 8.13

3. Why is a harmonious, stable home particularly important during middle childhood?

Middle childhood is a time when children really need continuity, not change; it’s a time when they need peace, not conflict. Routine is important to children’s sense of security, so disruptions in home life are especially challenging for this age group.

Question 8.14

4. Describe the characteristics of four different family structures.

The family structures discussed in the text include (1) nuclear: two parents and their children; (2) single-

Question 8.15

5. How do children benefit from a nuclear family structure?

Nuclear families tend to function best, at least in part because the people who marry tend to be better educated and to stay married. Having married parents benefits children by increasing the likelihood of parental involvement and decreasing the likelihood of neglect and abuse. Household income for nuclear families is also higher than for single-

Question 8.16

6. List three reasons why the single-

(1) Lower income; (2) less stability; and (3) less parental availability to meet children’s needs.

Question 8.17

7. In what ways are family structure and family function affected by culture?

Two-

Question 8.18

8. Using the family-

The family-

Question 8.19

9. How can researchers determine whether family conflict affects children directly, not merely through inherited genetic tendencies?

Researchers can employ a longitudinal study such as the one discussed in the text, in which several hundred pairs of identical and fraternal twins, all married with adolescent children, were studied. Each teenager was compared to his or her cousin, and researchers found that although genes were somewhat influential, whether the adolescents actually witnessed conflict was crucial.