10.2 Play

Play is timeless and universal—

There are echoes of this controversy in preschool education, as explained in Chapter 9. Some educators want children to focus on reading and math; others predict emotional and academic problems for children who rarely play (Hirsh-

281

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

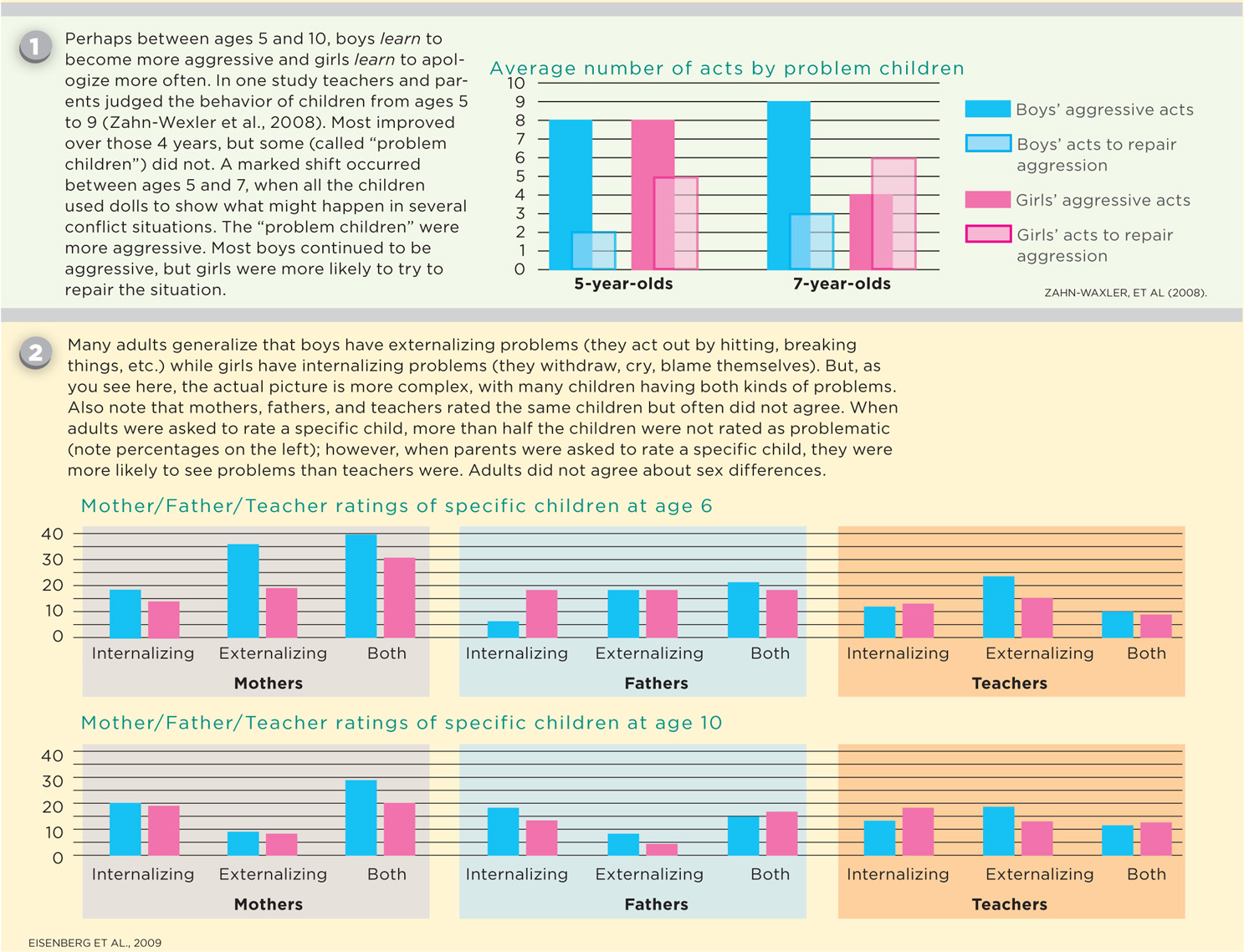

Sex Differences and Similarities

Humans tend to exaggerate differences and forget how much we have in common. Despite the common phrase “opposite sex,” most of our biological characteristics except sex organs are the same. The studies presented below are complex, but the bottom line is the same as the top: Whenever sex differences appear, be cautious—

DIFFERENCES IN PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

For children under age 10, boys have higher rates of psychopathology, although specific ratios vary by cohort and location. The most dramatic gender difference in rates of psychopathology is found with attention-

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL, 2011

SOME COMPLICATIONS

Every study that details sex differences in children’s behavior reports a complex picture.

282

Playmates

Young children play best with peers, that is, people of about the same age and social status. Although even infants are intrigued by other small children, most infant play is either solitary or with a parent. Some maturation is required for social play with peers.

At first, children are too self-

Parents have an obvious task in this regard: Find peers and arrange play dates. Of course, some parents play with their children, which benefits both of them. But even the most playful parent is outmatched by another child at negotiating the rules of tag, at play-

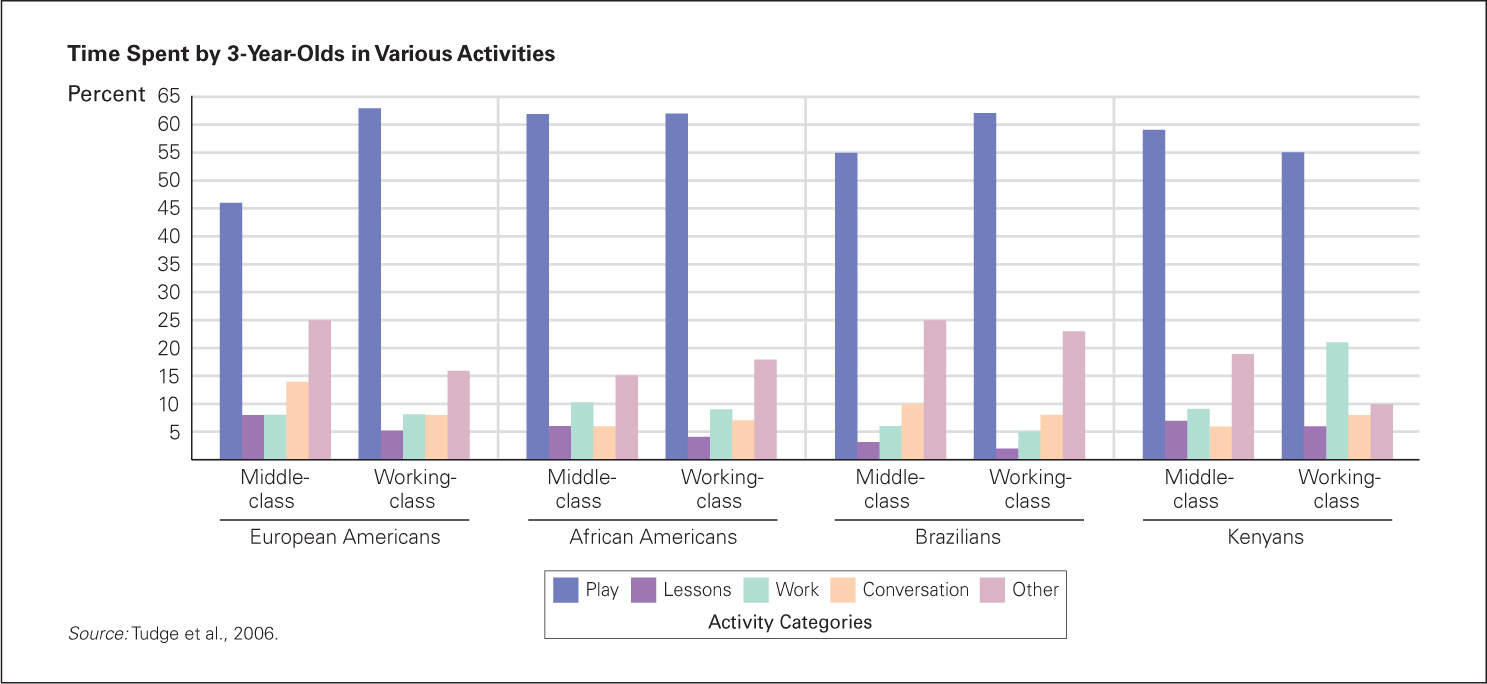

Culture and Cohort

All young children play; “everywhere, a child playing is a sign of healthy development” (Gosso, 2010, p. 95). Everywhere, play is the prime activity of even very young children, as illustrated in Figure 10.1. Basic play is similar in every culture, such as throwing and catching; pretending to be adults; drawing with chalk, markers, sticks, or what have you. Accordingly, developmentalists think play is experience-

Some specifics are experience-

283

As children grow older, play becomes more social, influenced by brain maturation, playmate availability, and the physical setting. One developmentalist bemoans the twenty-

Observation Quiz Does kicking a soccer ball, as shown above, require fine or gross motor skills?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Although controlling the trajectory of a ball with feet is a fine motor skill, these boys are using gross motor skills—

This opinion may be extreme, but it is echoed in more common concerns. As you remember, one dispute in preschool education is the proper balance between unstructured, creative play and teacher-

That was true in the United States a century ago. In 1932 the American sociologist Mildred Parten described the development of five kinds of social play, each more advanced than the previous one:

- Solitary play: A child plays alone, unaware of any other children playing nearby.

- Onlooker play: A child watches other children play.

- Parallel play: Children play with similar objects in similar ways but not together.

- Associative play: Children interact, sharing material, but their play is not reciprocal.

- Cooperative play: Children play together, creating dramas or taking turns.

Parten thought that progress in social play was age-

Research on contemporary children finds much more age variation. Many Asian parents successfully teach 3-

Active Play

Children need physical activity to develop muscle strength and control. Peers provide an audience, role models, and sometimes competition. For instance, running skills develop best when children chase or race each other, not when a child runs alone. Gross motor play is favored among young children, who enjoy climbing, kicking, and tumbling (Case-

Active social play—

284

Active play advances planning and self-

Rough-and-Tumble Play

rough-

The most common form of active play is called rough-

If a young male monkey wanted to play, he would simply catch the eye of a peer and then run a few feet away. This invitation to rough-

When the scientists returned to London, they saw that human youngsters, like baby monkeys, also enjoy rough-

Rough-

Many scientists think that rough-

Drama and Pretending

sociodramatic play Pretend play in which children act out various roles and themes in stories that they create.

Another major type of active play is sociodramatic play, in which children act out various roles and plots. Through such acting, children:

- Explore and rehearse social roles

- Learn to explain their ideas and persuade playmates

- Practice emotional regulation by pretending to be afraid, angry, brave, and so on

- Develop self-

concept in a nonthreatening context

Sociodramatic play builds on pretending, which emerges in toddlerhood. But preschoolers do more than pretend; they combine their imagination with that of their friends, advancing in theory of mind (Kavanaugh, 2011). The beginnings of sociodramatic play are illustrated by the following pair, a 3-

285

| Boy: | Not good. You bad. |

| Girl: | Why? |

| Boy: | ’Cause you spill your milk. |

| Girl: | No. ’Cause I bit somebody. |

| Boy: | Yes, you did. |

| Girl: | Say, “Go to sleep. Put your head down.” |

| Boy: | Put your head down. |

| Girl: | No. |

| Boy: | Yes. |

| Girl: | No. |

| Boy: | Yes. Okay, I will spank you. Bad boy. [Spanks her, not hard] |

| Girl: | No. My head is up. [Giggles] I want my teddy bear. |

| Boy: | No. Your teddy bear go away.[At this point she asked if he was really going to take the teddy bear away.] |

| [from Garvey, reported in Cohen, 2006, p. 72] | |

Note the social interaction in this form of play, with the 3-

A slightly older girl might want to play with the boys, but the older boys usually do not allow her (Pellegrini, 2013). Boy-

Older preschoolers are not only more gender conscious, their sociodramatic play is much more elaborate. This was evident in four boys, about age 5, in a day-

| Tuomas: | And now he [Joni] would take me and would hang me … This would be the end of all of me. |

| Joni: | Hands behind. |

| Tuomas: | I can’t help it. I have to. [The two other boys follow his example.] |

| Joni: | I would put fire all around them.[All three brave boys lie on the floor with hands tied behind their backs. Joni piles mattresses on them, and pretends to light a fire, which crackles closer and closer.] |

| Tuomas: | Everything is lost.[One boy starts to laugh.] |

| Petterl: | Better not to laugh, soon we will all be dead…. I am saying my last words. |

| Tuomas: | Now you can say your last wish…. And now I say I wish we can be terribly strong.[At that point, the three boys suddenly gain extraordinary strength, pushing off the mattresses and extinguishing the fire. Good triumphs over evil, but not until the last moment, because, as one boy explains, “Otherwise this playing is not exciting at all.”] |

| [adapted from Kalliala, 2006, p. 83] | |

Good versus evil is a favorite theme of boys’ sociodramatic play, with danger part of the plot but victory in the end. By contrast, girls often act out domestic scenes, with themselves as the adults. In the same day-

286

The prevalence of sociodramatic play varies by family. Some cultures find it frivolous and discourage it; in other cultures, parents teach toddlers to be lions, or robots, or ladies drinking tea. Then children elaborate on those themes (Kavanaugh, 2011). Some children are avid television watchers, and they then act out superhero themes.

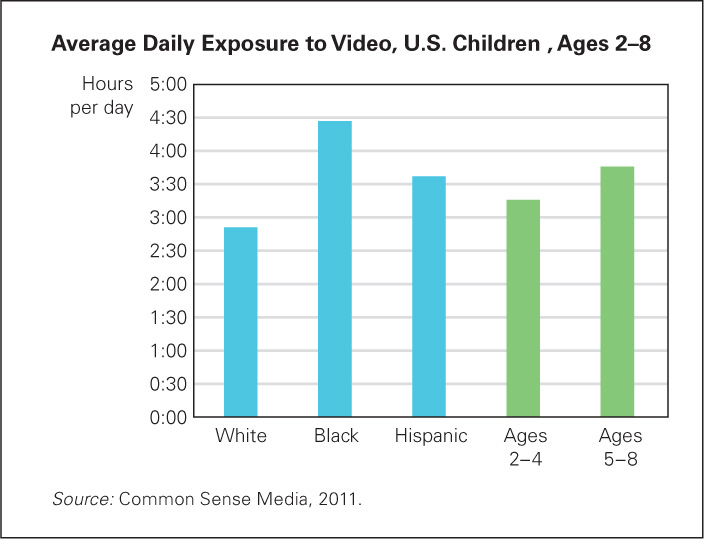

Television arouses concern among many developmentalists, who prefer that children’s dramas come from their own imagination, not from the media. Of course, some children learn from television and educational videos, especially if adults watch with them and reinforce the lessons. However, children on their own rarely select educational programs over fast-

Six major organizations (the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Psychiatric Association) recommend no electronic media at all for children under age 2 and strict limitations after that. The problem is not only that violent media teach aggression but also that all media take time from constructive interaction and creative play (see Figure 10.2).

SUMMING UP

All children everywhere in every era play during early childhood, which makes many developmentalists think play is essential for healthy development. Children benefit from play with peers, even more than from solitary play or play with adults. Specific forms of play vary by culture, gender, and SES. Rough-

287