10.3 Challenges for Caregivers

We have seen that young children’s emotions and actions are affected by many factors, including brain maturation, culture, and peers. Now we focus on another primary influence on young children: their caregivers.

For all children “parental involvement plays an important role in the development of both social and cognitive competence” (Parke & Buriel, 2006, p. 437). As more and more children spend long hours during early childhood with other adults, alternate caregivers become pivotal as well.

Caregiving Styles

Many researchers have studied the effects of parenting strategies and adult emotions. Although the temperament of the child and the patterns of the culture are always influential, adults vary a great deal in how they respond to children, with some parental practices leading to psychopathology while others encourage children to become outgoing, caring adults (Deater-

Baumrind’s Three Styles of Caregiving

Although thousands of researchers have traced the effects of parenting on child development, the work of one person, 50 years ago, continues to be influential. In her original research, Diana Baumrind (1967, 1971) studied 100 preschool children, all from California, almost all middle-

Baumrind found that parents differed on four important dimensions:

- Expressions of warmth. Some parents are warm and affectionate; others, cold and critical.

- Strategies for discipline. Parents vary in how they explain, criticize, persuade, and punish.

- Communication. Some parents listen patiently; others demand silence.

- Expectations for maturity. Parents vary in expectations for responsibility and self-

control.

On the basis of these dimensions, Baumrind identified three parenting styles (summarized in Table 10.1).

| Communication | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Style | Warmth | Discipline | Expectations of Maturity | Parent to Child | Child to Parent |

| Authoritarian | Low | Strict, often physical | High | High | Low |

| Permissive | High | Rare | Low | Low | High |

| Authoritative | High | Moderate, with much discussion | Moderate | High | High |

authoritarian parenting An approach to child rearing that is characterized by high behavioral standards, strict punishment for misconduct, and little communication from child to parent.

Authoritarian parenting. The authoritarian parent’s word is law, not to be questioned. Misconduct brings strict punishment, usually physical. Authoritarian parents set down clear rules and hold high standards. They do not expect children to offer opinions; discussion about emotions is especially rare. (One adult from such a family said that “How do you feel?” had only two possible answers: “Fine” and “Tired.”) Authoritarian parents seem cold, rarely showing affection.

288

permissive parenting An approach to child rearing that is characterized by high nurturance and communication but little discipline, guidance, or control. (Also called indulgent parenting.)

Permissive parenting. Permissive parents (also called indulgent) make few demands, hiding any impatience they feel. Discipline is lax, partly because they have low expectations for maturity. Permissive parents are nurturing and accepting, listening to whatever their offspring say, even if it is profanity or criticism of the parent.

Observation Quiz Is the father above authoritarian, authoritative, or permissive?

Answer to Observation Quiz: It is impossible to be certain based on one moment, but the best guess is authoritative. He seems patient and protective, providing comfort and guidance, neither forcing (authoritarian) nor letting the child do whatever he wants (permissive).

authoritative parenting An approach to child rearing in which the parents set limits but listen to the child and are flexible.

Authoritative parenting. Authoritative parents set limits, but they are flexible. They encourage maturity, but they usually listen and forgive (not punish) if the child falls short. They consider themselves guides, not authorities (unlike authoritarian parents) and not friends (unlike permissive parents).

neglectful/uninvolved parenting An approach to child rearing in which the parents are indifferent toward their children and unaware of what is going on in their children’s lives.

Other researchers describe a fourth style, called neglectful/uninvolved parenting, which may be confused with permissive but is quite different (Steinberg, 2001). The similarity is that neither permissive nor neglectful parents use physical punishment. However, neglectful parents are oblivious to their children’s behavior; they seem not to care. By contrast, permissive parents care very much: They defend their children, arrange play dates, and sacrifice to buy coveted toys.

Especially for Political Scientists Many observers contend that children learn their political attitudes at home, from the way their parents teach them. Is this true?

Response for Political Scientists: There are many parenting styles, and it is difficult to determine each one’s impact on children’s personalities. At this point, attempts to connect early child rearing with later political outlook are speculative.

The following long-

- Authoritarian parents raise children who become conscientious, obedient, and quiet but not especially happy. Such children tend to feel guilty or depressed, internalizing their frustrations and blaming themselves when things don’t go well. As adolescents, they sometimes rebel, leaving home before age 20.

- Permissive parents raise unhappy children who lack self-

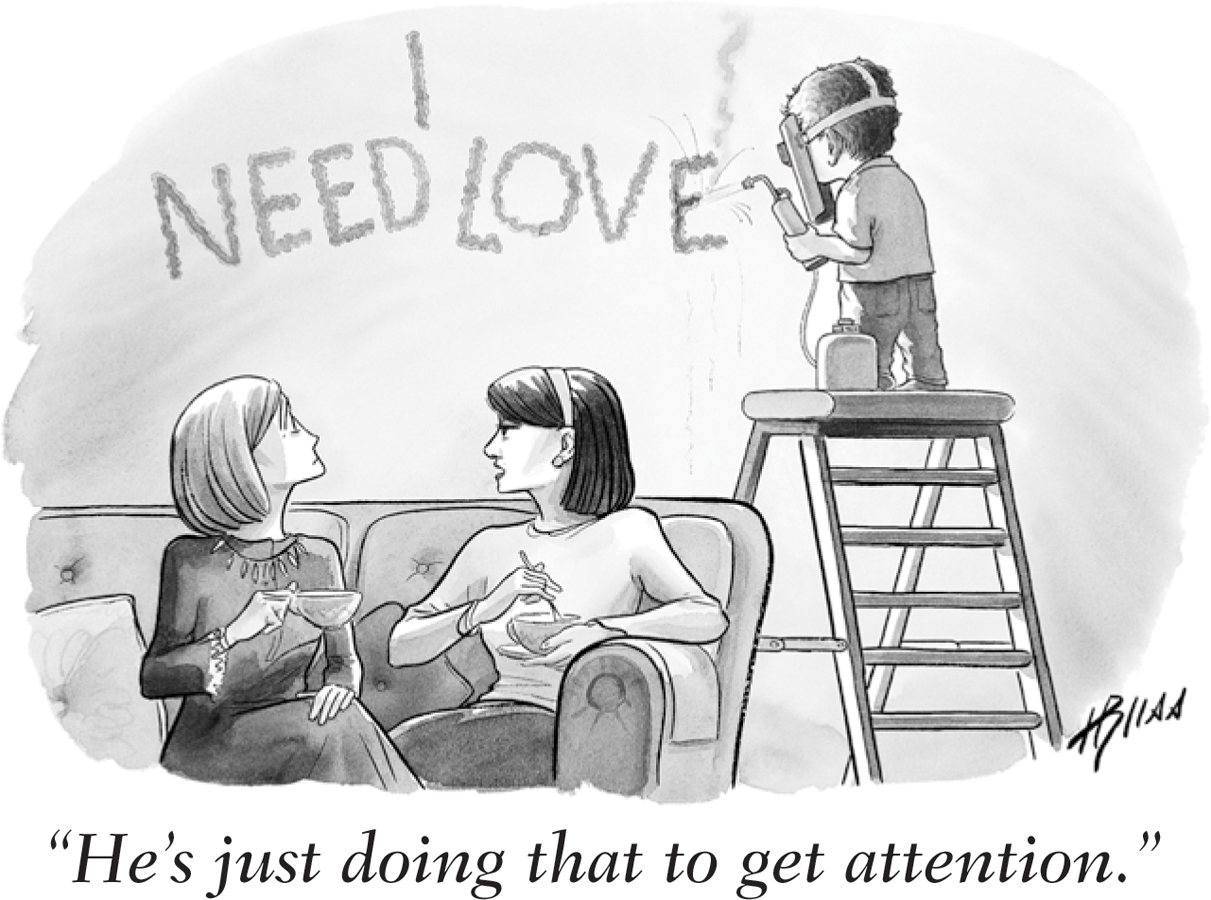

control, especially in the give- and- take of peer relationships. Inadequate emotional regulation makes them immature and impedes friendships, which is the main reason for their unhappiness. They tend to continue to live at home, still dependent on their parents, in early adulthood.  Pay Attention Children develop best with lots of love and attention. They shouldn’t have to ask for it!© THE NEW YORKER COLLECTION 2001 HARRY BLISS FROM CARTOONBANK.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Pay Attention Children develop best with lots of love and attention. They shouldn’t have to ask for it!© THE NEW YORKER COLLECTION 2001 HARRY BLISS FROM CARTOONBANK.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - Authoritative parents raise children who are successful, articulate, happy with themselves, and generous with others. These children are usually liked by teachers and peers, especially in cultures that value individual initiative (e.g., the United States).

- Neglectful/uninvolved parents raise children who are immature, sad, lonely, and at risk of injury and abuse, not only in early childhood but also lifelong.

Problems with Baumrind’s Styles

Baumrind’s classification schema is often criticized. Problems include the following:

- Her participants were not diverse in SES, ethnicity, or culture.

- She focused more on adult attitudes than on adult actions.

- She overlooked children’s temperamental differences.

- She did not recognize that some “authoritarian” parents are also affectionate.

- She did not realize that some “permissive” parents provide extensive verbal guidance.

We now know that a child’s temperament and the culture’s standards powerfully affect caregivers, as do the consequences of one style or another (Cipriano & Stifter, 2010). This is as it should be.

289

Fearful or impulsive children require particular styles (an emphasis on reassurance for the fearful ones and quite strict standards for the impulsive ones) that may seem permissive or authoritarian. Of course, every child needs guidance and protection, but not too much: Overprotection and hypervigilance seem to be both cause and consequence of childhood anxiety (McShane & Hastings, 2009; Deater-

A study of parenting at age 2 and children’s competence in kindergarten (including emotional regulation and friendships) found “multiple developmental pathways,” with the best outcomes dependent on both the child and the adult (Blandon et al., 2010). Such studies suggest that simplistic advice from a book, a professional, or a neighbor who does not know the temperament of the child may be misguided: Scientific observation of parent–

Cultural Variations

The significance of the context is particularly obvious when children of various ethnic groups are compared. It may be that certain alleles are more common in children of one group or another, and that difference may affect their temperament. However, much more influential are the attitudes and actions of adult caregivers.

U.S. parents of Chinese, Caribbean, or African heritage are often stricter than those of European backgrounds, yet their children develop better than if the parents were easygoing (Chao, 2001; Parke & Buriel, 2006). Latino parents are sometimes thought to be too intrusive, other times too permissive—

In a detailed study of 1,477 instances in which Mexican American mothers of 4-

Hailey [the 4-

[Livas-

Note that the mother’s first three efforts failed, and then a look accompanied by an explanation (albeit inaccurate in that setting, as no one could be hurt) succeeded. The researchers explain that these Mexican American families did not fit any of Baumrind’s categories; respect for adult authority did not mean a cold mother–

290

Given a multicultural and multicontextual perspective, developmentalists hesitate to be too specific in recommending any particular parenting style (Dishion & Bullock, 2002; J. G. Miller, 2004). That does not mean that all families function equally well—

Teaching Children to Be Boys or Girls

Biology determines whether a child is male or female. As you remember from Chapter 4, at about 8 weeks after conception, the SRY gene directs the reproductive organs to develop externally, and then male hormones exert subtle control over the brain, body, and later behavior. Without that gene, the fetus develops female organs, which produce female hormones that also affect the brain and behavior.

It is possible for sex hormones to be unexpressed prenatally, in which case the child does not develop like the typical boy or girl (Hines, 2013). That is very rare; most children are male or female in all three ways: chromosomes, genitals, and hormones. That is their nature, but obviously nurture affects their sexual development from birth until death.

During early childhood, sex patterns and preferences become important to children and apparent to adults. At age 2, children apply gender labels (Mrs., Mr., lady, man) consistently. By age 4, children are convinced that certain toys (such as dolls or trucks) and roles (not just Daddy or Mommy, but also nurse, teacher, police officer, soldier) are “best suited” for one sex or the other.

At least in the United States, sexual stereotypes are obvious and rigid between ages 3 and 6. Dynamic-

© ILYAS DEAN/THE IMAGE WORKS

291

Sex and Gender

sex differences Biological differences between males and females, in organs, hormones, and body type.

gender differences Differences in the roles and behaviors of males and females that are prescribed by the culture.

Many scientists distinguish sex differences, which are biological differences between males and females, from gender differences, which are culturally-

Young children are often confused about male-

In recent years, sex and gender issues have become increasingly complex—

Despite the increasing acceptance of sexual diversity, many preschoolers become remarkably rigid in their ideas of male and female. Already by age 3, boys reject pink toys and girls prefer them (LoBue & DeLoache, 2011). If young boys need new shoes, but the only ones that fit them are pink, most would rather go barefoot.

As already mentioned, girls tend to play with other girls and boys with other boys. Despite their parents’ and teachers’ wishes, children say, “No girls [or boys] allowed.” Most older children consider ethnic discrimination immoral, but they accept some sex discrimination (Møller & Tenenbaum, 2011). Why?

A dynamic-

Psychoanalytic Theory

phallic stage Freud’s third stage of development, when the penis becomes the focus of concern and pleasure.

Freud (1938) called the period from about ages 3 to 6 the phallic stage, named after the phallus, the Greek word for penis. At about 3 or 4 years of age, said Freud, boys become aware of their male sexual organ. They masturbate, fear castration, and develop sexual feelings toward their mother.

Oedipus complex The unconscious desire of young boys to replace their father and win their mother’s romantic love.

These feelings make every young boy jealous of his father—

superego In psychoanalytic theory, the judgmental part of the personality that internalizes the moral standards of the parents.

Freud believed that this ancient story dramatizes the overwhelming emotions that all boys feel about their parents—

That marks the beginning of morality, according to psychoanalytic theory. This theory contends that a boy’s fascination with superheroes, guns, kung fu, and the like arises from his unconscious impulse to kill his father. Further, an adult man’s homosexuality, homophobia, or obsession with guns, sins, and guilt arises from problems at the phallic stage.

292

Electra complex The unconscious desire of girls to replace their mother and win their father’s romantic love.

Freud offered several descriptions of the moral development of girls. One centers on the Electra complex (also named after a figure in classical mythology). The Electra complex is similar to the Oedipus complex in that the little girl wants to eliminate the same-

identification An attempt to defend one’s self-

According to psychoanalytic theory, at the phallic stage children cope with guilt and fear through identification; that is, they try to become like the same-

Since the superego arises from the phallic stage, and since Freud believed that sexual identity and expression are crucial for mental health, his theory suggests that parents encourage children to accept and follow gender roles. Many social scientists disagree. They contend that the psychoanalytic explanation of sexual and moral development “flies in the face of sociological and historical evidence” (David et al., 2004, p. 139).

Accordingly, I learned in graduate school that Freud was unscientific. However, as explained in Chapter 2, developmental scientists seek to connect research, theory, and experience. My own experience has made me rethink my rejection of Freud, as episodes with my four daughters illustrate.

My rethinking began with a conversation with my eldest daughter, Bethany, when she was about 4 years old:

| Bethany: | When I grow up, I’m going to marry Daddy. |

| Me: | But Daddy’s married to me. |

| Bethany: | That’s all right. When I grow up, you’ll probably be dead. |

| Me: | [Determined to stick up for myself] Daddy’s older than me, so when I’m dead, he’ll probably be dead, too. |

| Bethany: | That’s OK. I’ll marry him when he gets born again. |

I was dumbfounded, without a good reply. I had no idea where she had gotten the concept of reincarnation. Bethany saw my face fall, and she took pity on me:

| Bethany: | Don’t worry, Mommy. After you get born again, you can be our baby. |

The second episode was a conversation I had with my daughter Rachel when she was about 5:

| Rachel: | When I get married, I’m going to marry Daddy. |

| Me: | Daddy’s already married to me. |

| Rachel: | [With the joy of having discovered a wonderful solution] Then we can have a double wedding! |

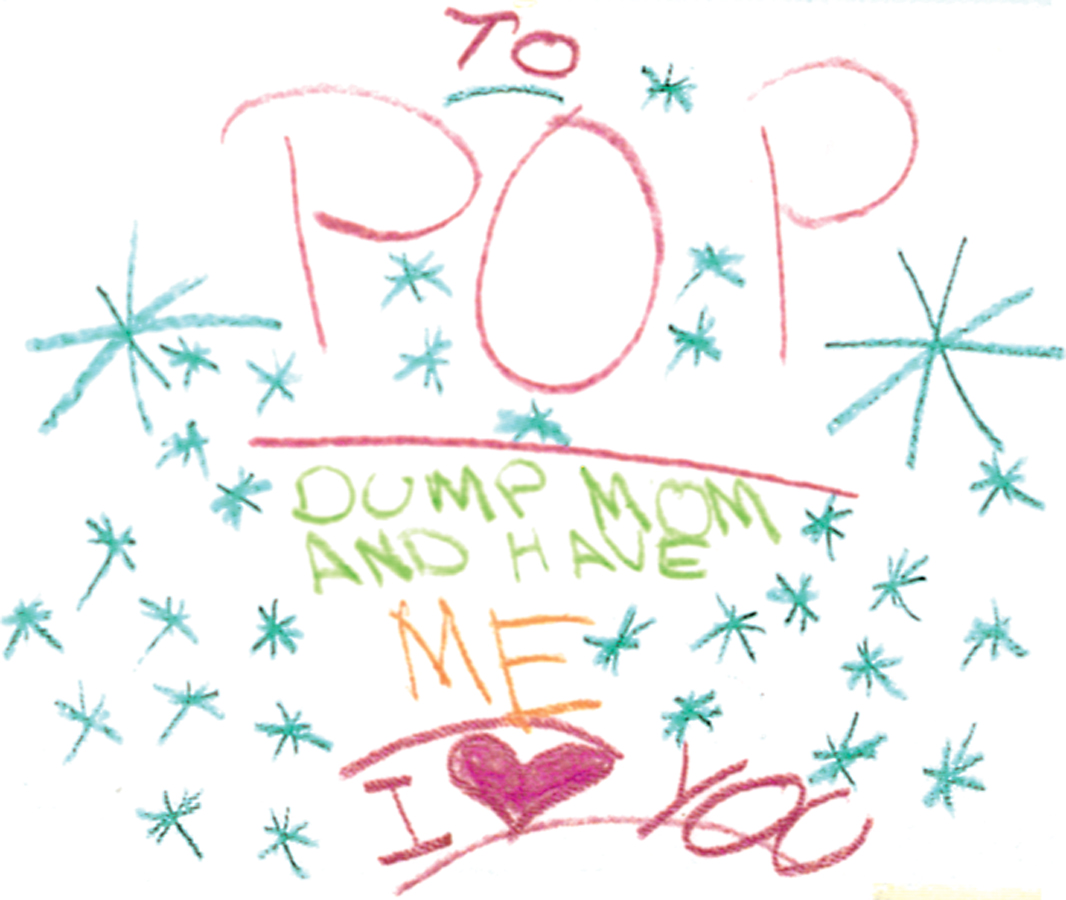

The third episode was considerably more graphic. It took the form of a “Valentine” left on my husband’s pillow on February 14th by my daughter Elissa (see Figure 10.3).

Finally, when Sarah turned 5, she also said she would marry her father. I told her she couldn’t, because he was married to me. Her response revealed one more hazard of watching TV: “Oh, yes, a man can have two wives. I saw it on television.”

As you remember from Chapter 1, a single example (or four daughters from one family) does not prove that Freud was correct. I still think Freud was wrong on many counts. But his description of the phallic stage seems less bizarre than I once thought.

Other Theories of Gender Development

Although most psychologists have rejected Freud’s theory regarding sex and gender, many other theories explain the young child’s sex and gender awareness.

293

Behaviorists believe that virtually all roles, values, and morals are learned. To behaviorists, gender distinctions are the product of ongoing reinforcement and punishment, as well as social learning. Parents, peers, and teachers all reward behavior that is “gender appropriate” more than behavior that is “gender inappropriate” (Berenbaum et al., 2008).

For example, “adults compliment a girl when she wears a dress but not when she wears pants” (Ruble et al., 2006, p. 897), and a boy who asks for both a train and a doll for his birthday is likely to get the train. Boys are rewarded for boyish requests, not for girlish ones. Indeed, the parental push toward traditional gender behavior in play and chores is among the most robust findings of decades of research on this topic (Eagly & Wood, 2013).

Social learning is considered an extension of behaviorism. According to that theory, people model themselves after people they perceive to be nurturing, powerful, and yet similar to themselves. For young children, those people are usually their parents. As it happens, adults are the most sex-

Furthermore, although national policies (e.g., subsidizing preschool) impact gender roles and many fathers are involved caregivers, women in every nation do much more child care, house cleaning, and meal preparation than do men (Hook, 2010). Children follow those examples, unaware that the examples they see are caused partly by their very existence: Before children are born, many couples share domestic work.

gender schema A cognitive concept or general belief based on one’s experiences—

Cognitive theory offers an alternative explanation for the strong gender identity that becomes apparent at about age 5. Remember that cognitive theorists focus on how children understand various ideas. A gender schema is the child’s understanding of male-

Young children have many gender-

Remember that for preoperational children, appearance is crucial. When they see men and women style their hair, use makeup, and wear clothes in distinct, gender-

Sociocultural theory stresses the importance of cultural values and customs. Some cultural aspects are transmitted through the parents, as explained with behaviorism, but much more arises from the larger community. This varies from place to place and time to time, as would be expected for any cultural value.

Consider a meta-

Thus national culture affects even personal adult choices such as marriage partners. Children are influenced by norms—

This explains cultural differences in the strength of sexism, in that male/female divisions are much more dominant in some places than others. Specifics vary (a man holding the hand of another man is either taboo or expected, depending on local customs), but everywhere young children try to conform to what they observe as the norms of their culture.

294

Humanism stresses the hierarchy of needs, beginning with survival, then safety, then love and belonging. The final two needs—

Ideally, babies have all their basic needs met, and toddlers learn to feel safe, which makes love and belonging crucial during early childhood. Children increasingly strive for admiration from their peers. Therefore, the girls seek to be one of the girls and the boys to be one of the boys.

In a study of slightly older children, participants wanted to be part of same-

Evolutionary theory holds that sexual attraction is crucial for humankind’s most basic urge, to reproduce. For this reason, males and females try to look attractive to the other sex, walking, talking, and laughing in gendered ways. If girls see their mothers wearing make-

According to evolutionary theory, the species’ need to reproduce is part of everyone’s genetic heritage, so young boys and girls practice becoming attractive to the other sex. This behavior ensures that they will be ready after puberty to find each other and that a new generation will be born, as evolution requires.

Thus, according to this explanation, over millennia of human history, particular genes, chromosomes, and hormones have evolved to allow the species to flourish. It is natural for boys to be more active (rough-

What Is Best?

Each of the major developmental theories strives to explain the ideas that young children express and the roles they follow. No consensus has been reached. Regarding sex or gender, those who contend that nature is more important than nurture, or vice versa, tend to design, cite, and believe studies that endorse their perspective. Only recently has a true interactionist perspective been endorsed (Eagly & Wood, 2013).

These theories raise important questions: What gender or sex patterns should parents and other caregivers teach? Should every child learn to combine the best of both sexes (called androgyny), thereby causing gender stereotypes to eventually disappear as children become more mature, as happens with their belief in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy? Or should male–

Answers vary among developmentalists as well as among parents and cultures. This section refers to “challenges” for caregivers. Determining how to raise children who are happy with themselves but not prejudiced against those of the other sex is one challenge that all caregivers face.

SUMMING UP

Caregiving styles vary, ranging from very strict, cold, and demanding to very lax, warm, and permissive. Baumrind’s classic research categorized parenting as authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive; these categories still seem relevant, even though the original research was limited in many ways. In general, a middle ground–

295

One difficult question for parents is how to respond to the young child’s ideas and stereotypes about males and females, which tend to be quite rigid during early childhood. Norms are changing, which means that old theories and traditional responses may not be helpful. Freud’s ideas are no longer endorsed by most developmentalists. However, theorists differ in their explanations and interpretations of gender differences. Caregivers’ responses depend not only on their culture, but also on whether they believe the primary impetus for boy/girl behavior is nature or nurture.