11.4 Children with Special Needs

developmental psychopathology The field that uses insights into typical development to understand and remediate developmental disorders.

Developmental psychopathology links the study of usual development with the study of disorders (Cicchetti, 2013). Every topic already described, including “genetics, neuroscience, developmental psychology,…must be combined to understand how psychopathology develops and can be prevented” (Dodge, 2009, p. 413).

324

At the outset, four general principles of developmental psychopathology should be emphasized.

- Abnormality is normal. Most children sometimes act oddly. At the same time, children with serious disorders are, in many respects, like everyone else.

- Disability changes year by year. Most disorders are comorbid, which means that more than one problem is evident in the same person. Which particular disorder is most disabling at a particular time changes, as does the degree of impairment.

comorbid Refers to the presence of two or more unrelated disease conditions at the same time in the same person.

- Life may be better or worse in adulthood. Prognosis is difficult. Many children with severe disabilities (e.g., blindness) become productive adults. Conversely, some conditions (e.g., conduct disorder) may become more disabling.

- Diagnosis and treatment reflect the social context. In dynamic systems, each individual interacts with the surrounding setting—

including family, school, community, and culture— to modify, worsen, or even create psychopathology.

Causes and Consequences

Developmental psychopathology is a topic to be studied at every point of the life span because “[e]ach period of life, from the prenatal period through senescence, ushers in new biological and psychological challenges, strengths, and vulnerabilities” (Cicchetti, 2013, p. 458). Turning points, opportunities, and the influence of prior burdens appear at every age, as already noted in our discussion of epigenetics, of three forms of prevention, of environmental toxins, and of much else.

However, it is in middle childhood that children are first grouped by age and expected to start learning on schedule. For some parents and children, it suddenly becomes obvious that a particular child differs markedly from others the same age. Fortunately, most abnormalities can be mitigated if treatment is early and properly targeted.

Therein lies a problem: Although early treatment is more successful, early and accurate diagnosis is difficult, not only because many disorders are comorbid but also because symptoms differ by age. As you learned in Chapter 7, infants have temperamental differences that might or might not become problems, and Chapter 10 explained that some aggression is normal. When does unusual behavior signify a serious problem? Difference is not necessarily deficit—

multifinality A basic principle of developmental psychopathology that holds that one cause can have many (multiple) final manifestations.

Two basic principles of developmental psychopathology lead to caution in diagnosis and treatment (Cicchetti & Toth, 2009; Cicchetti, 2013). First is multifinality, which means that one cause can have many (multiple) final manifestations. For example, an infant who has been flooded with stress hormones may become a hyper-

equifinality A basic principle of developmental psychopathology that holds that one symptom can have many causes.

The second principle is equifinality (equal in final form), which means that one symptom can have many causes. For instance, a nonverbal child may be autistic, hard of hearing, not comfortable in the dominant language, or pathologically shy.

The complexity of diagnosis is evident in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), often referred to as DSM-

325

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

attention-

Someone with attention-

Essentially a child with ADHD is more easily distracted and more often in motion than the average child. For instance, when sitting down to do schoolwork, the child might look up, ask questions, get a drink, fidget, squirm, tap the table, jiggle his or her legs, and go to the bathroom—

Problems with Diagnosis

A major problem in diagnosing ADHD is that there is no biological marker for it (such as a substance in the blood or an abnormality in the brain), yet some children find it almost impossible to sit quietly and concentrate. Those children might be punished and excluded because they are not like other children.

Moreover, ADHD is comorbid with many other conditions, including biological problems such as sleep deprivation or allergic reactions, and psychological disorders, including those soon to be discussed (Miklowitz & Cicchetti, 2010). This is an example of equifinality in that explosive rages and, later, deep regret are typical for children with many disorders, including ADHD.

Although the U.S. rates were about 5 percent in 1980, recent data find that 7 percent of all 4-

Rates of ADHD in most other nations are lower than in the United States, but they are rising everywhere (e.g., Al-

- Misdiagnosis. If ADHD is diagnosed when another disorder is the problem, treatment might make the problem worse, not better (Miklowitz & Cicchetti, 2010). Many psychoactive drugs alter moods, so a child with bipolar disorder (formerly called manic-

depressive disorder) might be harmed by drugs that help children with ADHD. - Drug abuse. Although alleviating the symptoms of ADHD with drugs actually reduces the incidence of later drug abuse, some adolescents may seek a diagnosis of ADHD in order to legally obtain amphetamines, which are often abused.

- Normal behavior considered pathological. In young children, high activity, impulsiveness, and curiosity are normal but may be disruptive to parents or teachers. Some normal children, who will become more mature in time, may be convinced that they are abnormal. ADHD is at least twice as common among boys than among girls—

might some unconscious sexism affect the diagnosis?

Especially for Health Workers Parents ask that some medication be prescribed for their kindergarten child, who they say is much too active for them to handle. How do you respond?

Response for Health Workers: Medication helps some hyperactive children but not all. It might be useful for this child, but other forms of intervention should be tried first. Compliment the parents on their concern about their child, but refer them to an expert in early childhood for an evaluation and recommendations. Behavior-

Treatment for ADHD involves (1) counseling and training for the family and the child, (2) showing teachers how to help the children learn, and (3) medication. But, as equifinality suggests, most disorders vary in causes so that treatment that helps one child does not necessarily work for another (Mulligan et al., 2013). Because many adults are upset by what young children normally do and because any physician can write a prescription to quiet a child, developmentalists fear that thousands of children are overmedicated.

Drug Treatment for ADHD and Other Disorders

The most common and also the most controversial treatment for many childhood disorders is medication. In the United States, more than 2 million people younger than 18 take prescription drugs to regulate their emotions and behavior. The rate is about 14 percent for teenagers (Merikangas et al., 2013), about 10 percent for 6-

The most commonly prescribed drug for ADHD is Ritalin, but at least 20 other psychoactive drugs treat depression, anxiety, developmental delay, autism, bipolar disorder, and many other conditions in middle childhood. Because few psychoactive drugs have been adequately tested for children, many drugs are prescribed “off label”—that is, they are not approved for patients of a particular age or condition. Much of the American public is suspicious of any childhood psychiatric medicine (Moldavsky & Sayal, 2013; Rose, 2008), as are people worldwide. In China, for instance, parents rarely use psychoactive medication for children: A Chinese child with ADHD symptoms is thought to need correction rather than medication (Rongwang et al., 2013).

Many child psychologists believe that drugs can be helpful, and they worry that the public is oblivious to the devastation and lost learning that occur when a child’s serious disorder is not recognized or treated. But they also raise concerns (Mayes et al., 2009). Finding the best drug at the right strength is difficult, in part because each child’s genes and personality are unique.

Moreover, since weight and metabolism change every year, the right dose at one time is wrong at another. Only half of all children who take psychoactive drugs are evaluated and monitored by a mental health professional (Olfson et al., 2010).

Most developmentalists accept the research showing that medication helps children with emotional problems, particularly ADHD (Epstein et al., 2010). Many also believe that contextual interventions (instructing parents and teachers on child management) should be tried first (Daley et al., 2009; Leventhal, 2013; Pelham & Fabiano, 2008). Careful, individualized treatment is needed to find the right medication for each child.

By contrast, parents tend to be either pro-

African American and Hispanic children are less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, especially when they do not have health insurance. When they are diagnosed, their parents are less likely to give them medication (Morgan et al., 2013). The reasons include fragmented medical care and distrust of doctors (Miller et al., 2009).

327

As a result of the discrepancy between public attitudes and research data, some children who would benefit from drugs are never medicated, and other children take medication without the necessary monitoring. Even with medication, problems may continue.

For example, a group of children with ADHD from many cities in the United States and Canada were given appropriate medication, carefully calibrated, and their symptoms improved. However, eight years later, many had stopped taking their medicine. At this follow-

When appropriately used, drugs for ADHD may help children make friends, learn in school, feel happier, and behave better. These drugs also seem to help adolescents and adults with ADHD (Surman et al., 2013). However, as the just cited longitudinal study of ADHD children found, problems do not disappear: adolescents and adults who were diagnosed with ADHD as children are less successful academically and personally, whether or not they were medicated (Brooke et al., 2013). Drugs may help, but they are not the solution. The following A Case to Study makes this clear.

A CASE TO STUDY

Lynda Is Getting Worse

Even experts differ in diagnosis and treatment. For instance, one study asked 158 child psychologists to diagnose an 11-

Parents say Lynda has been hyperactive, with poor boundaries and disinhibited behavior since she was a toddler…. Lynda has taken several stimulants since age 8. She is behind in her school work, but IQ normal…. At school she is oppositional and “lazy” but not disruptive in class. Psychological testing, age 8, described frequent impulsivity, tendencies to discuss topics unrelated to tasks she was completing, intermittent expression of anger and anxiety, significantly elevated levels of physical activity, difficulties sitting still, and touching everything. Over the past year Lynda has become very angry, irritable, destructive and capricious. She is provocative and can be cruel to pets and small children. She has been sexually inappropriate with peers and families, including expressing interest in lewd material on the Internet, Play Girl magazine, hugging and kissing peers. She appears to be grandiose, telling her family that she will be attending medical school, or will become a record producer, a professional wrestler, or an acrobat. Throughout this period there have been substantial marital difficulties between the parents.

[Dubicka et al., 2008, appendix p. 3]

What is the problem here? Most (81 percent) of the clinicians diagnosing Lynda thought she had ADHD, and most thought she had another disorder as well. In this study, about half of the clinicians were British, and half American. The Americans were much more likely to suggest a second and third disorder, with 75 percent of them specifying bipolar disorder. Only 33 percent of the British psychologists agreed, although they were more likely to diagnose an adjustment disorder (Dubicka et al., 2008).

From a developmental perspective, it is noteworthy, but not unusual, that the family context or teacher’s attitudes do not seem to be reflected in the diagnoses of the clinicians. Testing at age 8 seems to have focused only on Lynda, not on the parents. Lynda is in regular classes at school. In fact, for both nature and nurture reasons, parents who have ADHD or mood disorders are more likely to have children with disorders, and it would have made sense for the parents to be tested and perhaps treated.

In this case, her parents thought Lynda had ADHD since toddlerhood; a pediatrician agreed and at age 8 put her on drugs. Now, at age 11, she seems to be getting worse, not better, while her parents are increasingly hostile to each other. The experts differ, partly because of cultural differences.

It is impossible to know what would have happened if intensive intervention had taken place for the entire family when Lynda was a toddler. Using a family-

328

Specific Learning Disorders

specific learning disorder (learning disability) A marked deficit in a particular area of learning that is not caused by an apparent physical disability, by an intellectual disability, or by an unusually stressful home environment.

The DSM-

Most learning disorders are not debilitating (e.g., the off-

Dyslexia

dyslexia Unusual difficulty with reading; thought to be the result of some neurological underdevelopment.

The most commonly diagnosed learning disability is dyslexia—unusual difficulty with reading. No single test accurately diagnoses dyslexia (or any learning disability) because every academic achievement involves many distinct factors (Riccio & Rodriguez, 2007). One child with a reading disability might have trouble sounding out words but might excel in comprehension and memory of printed text; another child might have the opposite problem. Dozens of types and causes of dyslexia have been identified.

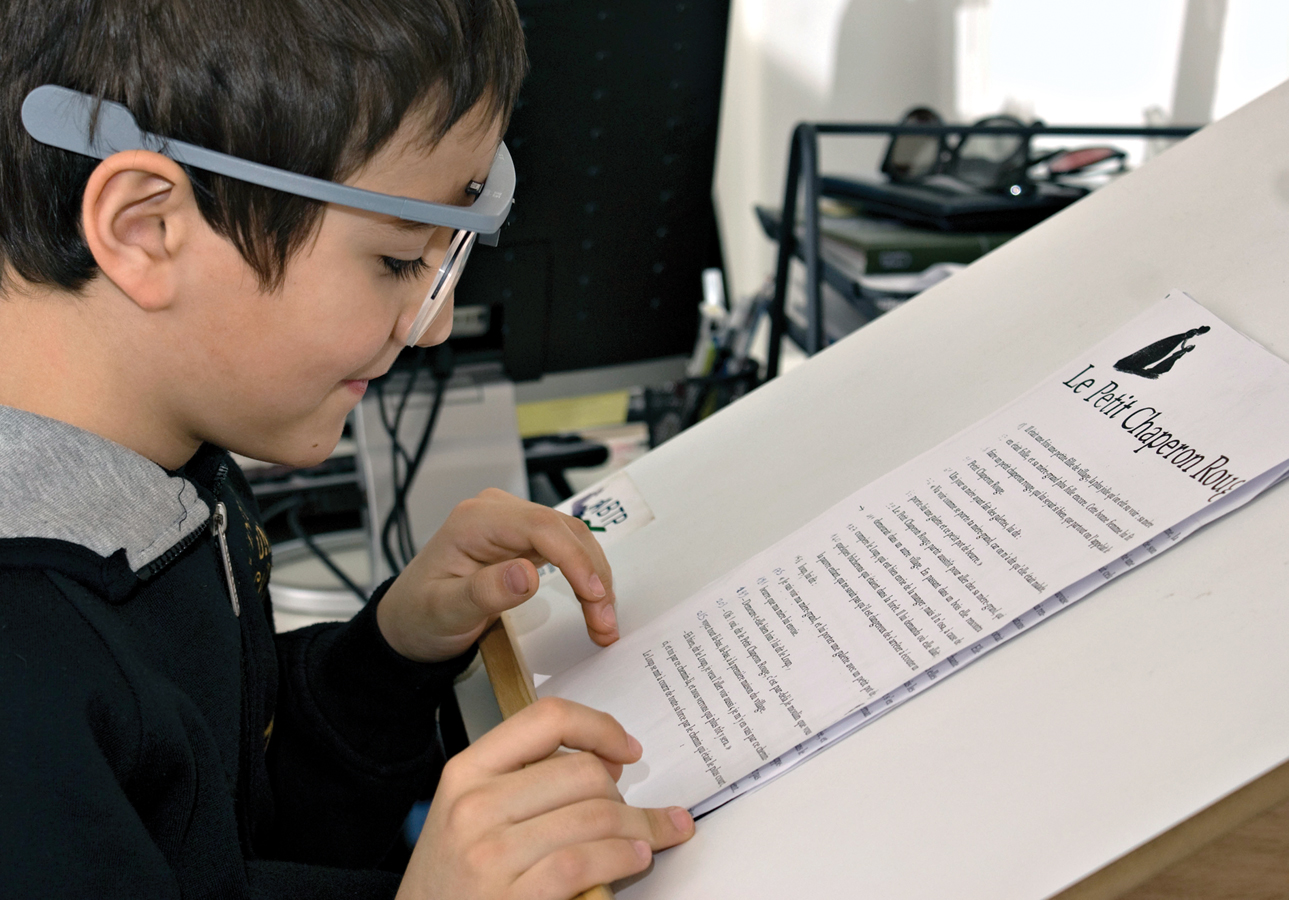

Early theories hypothesized that visual difficulties—

Traditionally, dyslexia was diagnosed only if a child had difficulty reading despite normal IQ, normal hearing and sight, and normal behavior. However, DSM-

Dyscalculia

dyscalculia Unusual difficulty with math, probably originating from a distinct part of the brain.

Similar suggestions apply to learning disabilities in math, called dyscalculia. Dyslexia and dyscalculia are often comorbid, although each originates from a distinct part of the brain. Early help with counting and math concepts (long before first grade) can help prevent the emotional anxiety that occurs if a child is made to feel stupid (Butterworth et al., 2011).

Remember that in early childhood most children can look at a series of dots and estimate how many there are. Perhaps even in infancy, a child with dyscalculia cannot estimate how many dots are present. Basic number sense is deficient in children with dyscalculia, which provides a clue for early remediation (Piazza et al., 2010).

329

When a young child has trouble performing math tasks that other children can do easily, dyscalculia is suspected. For example, a second-

Every person, learning disabled or not, has strengths and interests, and almost everyone can learn basic skills if they have extensive and specific help, encouragement, and practice. The problem with learning disabilities is that most children are not diagnosed early enough, with sufficient detail, or given individualized education.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

autism spectrum disorder A developmental disorder marked by difficulty with social communication and interaction—

Of all the children with special needs, those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are probably the most troubling. Their problems are severe and the causes of and treatments for autism are hotly disputed.

Most children with autism can be spotted in the first year of life, but some seem normal and only later does autism become evident. Many children with symptoms of autism but who learned to talk on time were formerly considered to have Asperger syndrome. Now the diagnosis would be “autism spectrum disorder without language or intellectual impairment” (DSM-

Symptoms

Autism is characterized by woefully inadequate social understanding. Almost a century ago, it was considered a single, rare disorder affecting fewer than 1 in 1,000 children with “an extreme aloneness that, whenever possible, disregards, ignores, shuts out anything…from the outside” (Kanner, 1943). Children who developed slowly but were not so withdrawn were diagnosed as being mentally retarded or as having a “pervasive developmental disorder.” (Note that the term “mental retardation,” which was used in DSM-

Much has changed in the past decades. Now many children who would have been considered intellectually disabled are said to have an autism spectrum disorder, which characterizes as many as 1 in every 88 children (almost five times as many boys as girls and about a third more European Americans than Hispanic, Asian, or African Americans) (Lord & Bishop, 2010). Some children “on the spectrum” do not seem to be intellectually delayed.

The two main signs of an autism spectrum disorder are: (1) problems in social interaction and the social use of language, and (2) restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. Children with any form of ASD find it difficult to understand the emotions of others, which makes them feel alien, like “an anthropologist on Mars,” as Temple Grandin, an educator and writer with autism, expressed it (quoted in Sacks, 1995). Consequently, they are less likely to talk, play, or otherwise interact with anyone, and they usually are delayed in developing a theory of mind (Senju et al., 2010).

Autism spectrum disorders include many symptoms of varied severity. Some children never speak, rarely smile, and often play for hours with one object (such as a spinning top or a toy train). Others are called “high functioning”; they are often extremely talented in some specialized area, such as drawing or geometry. Many are brilliant in unusual ways (Dawson et al., 2007), including Grandin, a well-

330

Most children with autism spectrum disorder show signs in early infancy (no social smile, for example, or less gazing at faces). Some improve by age 3, whereas others deteriorate. Amazingly, 40 percent of parents who were told their child has autism said later that their child no longer had it (Kogan et al., 2009). On the other hand, late onset of autism spectrum disorder occurs with Rett syndrome, in which a newborn girl (never a boy; they do not survive if they have the X-

Many children with autism have an opposite problem—

Far more children have autism spectrum disorders now than in 1990, either because the incidence of this disorder has increased or because more children receive that diagnosis. The new criteria in DSM-

Underlying that estimate is the reality that no definitive measure diagnoses autistic spectrum disorder: Many adults are socially inept, insensitive to other people’s emotions, and poor at communication—

Treatment

When a child is diagnosed with ASD, parents’ responses vary from irrational hope to deep despair, from blaming doctors and chemical additives to feeling guilty for what they did wrong. Developmentalists generally believe that genes are one factor in autism but that parents are not at fault. Parents and teachers can be very helpful, however, if they cooperate with one another while the child is young. Even when all the adults work in harmony, treatment is complicated.

Equifinality certainly applies to autism: A child can have autistic symptoms for many reasons, which makes treatment difficult, as an intervention that seems to help one child proves worthless for another. It is known, however, that biology is crucial (genes, birth complications, prenatal injury, or perhaps chemicals) and that family nurture is not the cause (G. Dawson, 2010). One family factor may be influential, however: having one baby soon after another. Children born less than a year after a previous birth are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed as autistic compared with children born three or more years later (Cheslack-

A vast number of treatments have been used to help children with autism spectrum disorders, but none of them has been completely successful. Some parents are convinced that a particular treatment helped their child, whereas other parents say that the same treatment failed.

Scientists disagree as well. For instance, one popular treatment is putting the child in a hyperbaric chamber to breathe more concentrated oxygen than is found in everyday air. Two studies of hyperbaric treatments—

331

Treatment is further complicated when parents and medical professionals disagree, as illustrated by the controversy about thimerosal, an antiseptic containing mercury that was formerly used in childhood immunizations. Many parents of children with the symptoms of autism first noticed their infants’ impairments after their vaccinations and believed thimerosal was the cause. No scientist who examines the evidence agrees: Extensive research has disproven the immunization hypothesis many times (Offit, 2008).

More than a decade ago thimerosal was removed from vaccines given to infants, but the rates of autism are still rising. Many doctors fear that parents who cling to this hypothesis are not only wrong but are also harming millions of children who suffer needless illnesses because their parents refuse to immunize them.

Some children with autism are treated biologically, with special diets, vitamin supplements, hormones (oxytocin), or psychoactive drugs. Each of these strategies is used by some advocates who find symptoms improving, but none has proven successful at relieving the basic condition.

Many behavioral methods to improve talking and socialization have also been tried, again with mixed results (Granpeesheh et al., 2009; Hayward et al., 2009; Howlin et al., 2009). Early and individualized education of both the child and the parents has had some success.

Special Education

The overlap of the biosocial, cognitive, and psychosocial domains is evident to developmentalists, who envision each child’s growth in every area as affected by the other areas. However, whether or not a child is designated as needing special education is not straightforward, nor is it closely related to specific special needs.

Changing Laws and Practices

least restrictive environment (LRE) A legal requirement that children with special needs be assigned to the most general educational context in which they can be expected to learn.

In the United States, recognition that the distinction between normal and abnormal is not clear-

LRE has usually meant educating children with special needs in a regular class, a practice once called mainstreaming, rather than in a special classroom or school. Sometimes a child is sent to a resource room, with a teacher who provides targeted tutoring. Sometimes a class is an inclusion class, which means that children with special needs are “included” in the general classroom, with “appropriate aids and services” (ideally from a trained teacher who works with the regular teacher) (Kalambouka et al., 2007).

response to intervention (RTI) An educational strategy intended to help children who demonstrate below-

The latest educational strategy in the United States is called response to intervention (RTI) (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009; Shapiro et al., 2011; Ikeda, 2012). All children in the early grades who are below average in achievement (which may be half the class) are given some special intervention. Most of them respond by improving their achievement, but for those who do not, more intervention occurs. If there is no response to repeated intervention, the child is referred for testing and observation to diagnose the problem.

332

individual education plan (IEP) A document that specifies educational goals and plans for a child with special needs.

Professionals use a battery of tests (not just IQ or achievement tests) to reach their diagnosis and develop recommendations. If they find that a child has special needs, they discuss an individual education plan (IEP) with the parents, to specify educational goals for the child.

Cohort and Culture

Developmentalists consider a child’s biological and brain development as the starting point for whatever special assistance will allow the child to reach his or her full potential. Thus home and school practices are crucial.

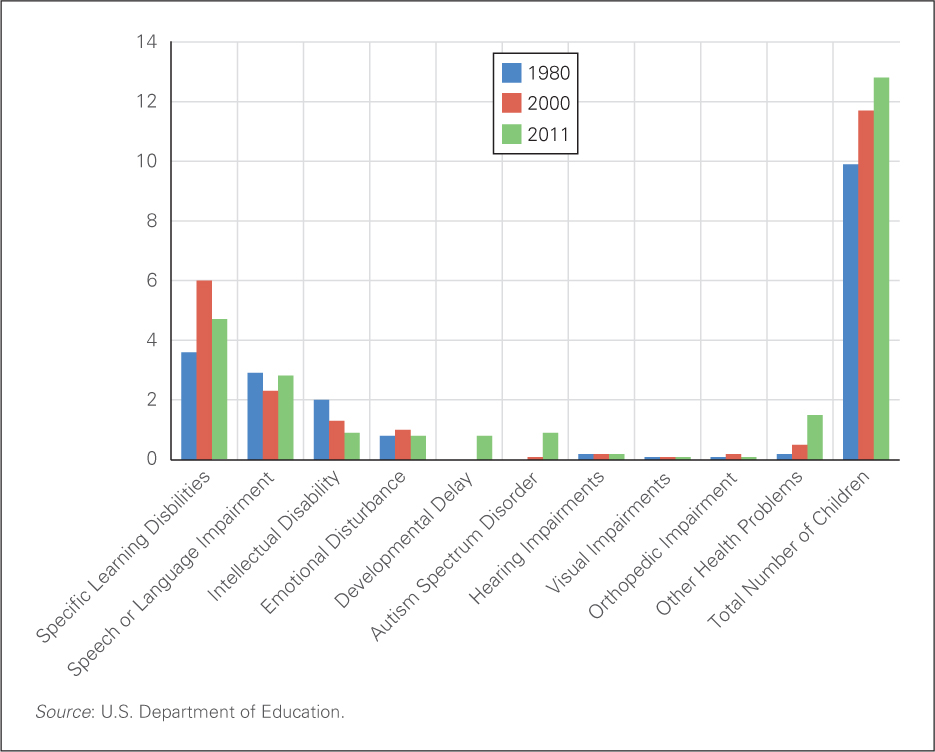

Among all the children in the United States who are recognized by educators as having special needs, historical shifts are notable. As Figure 11.5 shows, the proportion of children designated with special needs rose in the United States from 10 percent in 1980 to 13 percent in 2011, primarily because more children are considered learning disabled (National Center for Education Statistics, 2013). In 1975 the number was only 8 percent.

In 1980 almost one in 5 of the children that the school system categorized as having special needs was intellectually disabled. That category continues to shrink: in 2011 only one child in 14 was so designated. Autism and developmental delay were not recognized in 1980, but these diagnoses have increased notably since they were first introduced. Children with these disorders in 1980 were probably categorized as intellectually disabled (then called mentally retarded).

333

It is possible that contemporary children have a markedly different mix of special needs, but it is more likely that some rates have changed because the labels have changed. Note that there is still no separate category for ADHD. To receive special services, children with ADHD usually have to prove they are learning disabled.

In the international arena, the connection between special needs and education varies for cultural reasons, not child-

Gifted and Talented

Children who are unusually gifted are often thought to have special needs as well, but they are not covered by the federal laws. Instead, each state of the United States selects and educates gifted and talented children in a particular way, a variation that leads to controversy.

A scholar writes: “The term gifted…has never been more problematic than it is today” (Dai, 2011, p. 8). Educators, political leaders, scientists, and everyone else argue about who is gifted and what should be done about them. Are gifted children unusually intelligent, or talented, or creative? Should they be skipped, segregated, enriched, or left alone?

A hundred years ago, the definition of gifted was simple: high IQ. A famous longitudinal study followed a thousand “genius” children, all of whom scored about 140 on the Stanford-

acceleration Educating gifted children alongside other children of the same mental, not chronological, age.

A hundred years ago, school placement was simple, too: The gifted were taught with children who were their mental age, not their chronological age. This practice was called acceleration. Today that is rarely done because many accelerated children were bullied, unhappy, and never learned how to get along with others. As one woman remembers:

Nine-

[Rachel, quoted in Freeman, 2010, p. 27]

Weeds grow no matter where they are planted, and research on thousands of children has found that while the gifted learn differently from other children, they are neither more nor less likely to need emotional and social education. Educating the whole child, not just the mind, is required (Winner, 1996).

Another type of special child is designated precocious in one of Gardner’s nine intelligences. Such children are often called talented instead of gifted. Mozart was one, composing music at age 3; so was Pablo Picasso, creating works of art at age 4.

Historically, many famous musicians, artists, and scientists were child prodigies whose fathers recognized their talent (often because the father was talented) and taught them. Mozart’s father transcribed his earliest pieces and toured Europe with his gifted son. Picasso’s father removed him from school in second grade so he could create all day (Pablo said he never learned to read or write).

334

Although such intense early education nourished talent, neither Mozart nor Picasso had happy adult lives. Similar patterns are still apparent, as exemplified by gifted athletes (e.g., Tiger Woods and Steffi Graf) as well as those in more erudite specialties. Here is one example:

Sufiah Yusof started her maths degree at Oxford [the leading University in England] in 2000, at the age of 13. She too had been dominated and taught by her father. But she ran away the day after her final exam. She was found by police but refused to go home, demanding of her father in an email: “Has it ever crossed your mind that the reason I left home was because I’ve finally had enough of 15 years of physical and emotional abuse?” Her father claimed she’d been abducted and brainwashed. She refuses to communicate with him. She is now a very happy, high-

[Freeman, 2010, p. 286]

A third kind of child who might need special education is the unusually creative one (Sternberg et al., 2011). They are divergent thinkers, finding many solutions and even more questions for every problem. Such students joke in class, resist drudgery, ignore homework, and bedevil their teachers. They may become innovators, inventors, and creative forces of the future.

Creative children do not conform to social standards. They are not convergent thinkers, who choose the correct answer on school exams. One such person was Charles Darwin, whose “school reports complained unendingly that he wasn’t interested in studying, only shooting, riding, and beetle-

Since both acceleration and intense parental tutoring have led to later problems, a third education strategy has become popular, at least in the United States. Children who are bright, talented, and/or creative—

Neuroscience has recently discovered another advantage to gifted classes: brain development. Children who practice musical talents in early childhood develop specialized brain structures, as do child athletes and mathematicians. This suggests that neurological specialization occurs for every form of giftedness. Since plasticity means that all children learn whatever their context teaches, talents may be developed, not wasted, with special education.

Classes for gifted students require unusual teachers, bright and creative, able to appreciate divergent thinking and challenge the very bright. They must be flexible: providing a 7-

Flexible teachers must be carefully selected and chosen for gifted and talented children. However, every child may need such teachers, no matter what the child’s abilities or disabilities may be.

Some nations educate all children together, assuming that intelligence is not a matter of some children being unusually gifted as much as some children putting more effort into learning. Thus the teacher’s job is to motivate and challenge every child. Some gifted children benefit from special recognition in school, and some would be much better off if they were left alone, without teachers or parents expecting them to excel (Freeman, 2010).

335

As the Education of All Handicapped Children law states, all children can learn. But not all schools and teachers successfully teach them. Every special and ordinary form of education can benefit from what we know about children’s minds and how they learn (De Corte, 2013). That is the topic of the next chapter.

SUMMING UP

Many children have special learning needs that originate with problems in the development of their brains. Developmental psychopathologists emphasize that no one is typical in every way; the passage of time sometimes brings improvement to children with special needs and sometimes not. Children with attention-

336