12.3 Teaching and Learning

As we have just described, school-

International Schooling

Everywhere in the world children are taught to read, write, and do arithmetic. Because of brain maturation and sequenced learning, 6-

Nations also want their children to be good citizens. However, citizenship is not easy to teach. There is no consensus as to what that means or what developmental paths should be followed (Cohen & Malin, 2010).

Differences by Nation

Although literacy and numeracy (reading and math, respectively) are valued everywhere, many curriculum specifics vary by nation, by community, and by school. These variations are evident in the results of international tests, in the mix of school subjects, and in the relative power of parents, educators, and political leaders.

For example, daily physical activity is mandated in some schools but not in others. Many schools in Japan have swimming pools; virtually no schools in Africa or Latin America do. As you read in Chapter 11, some U.S. schools have no recess at all.

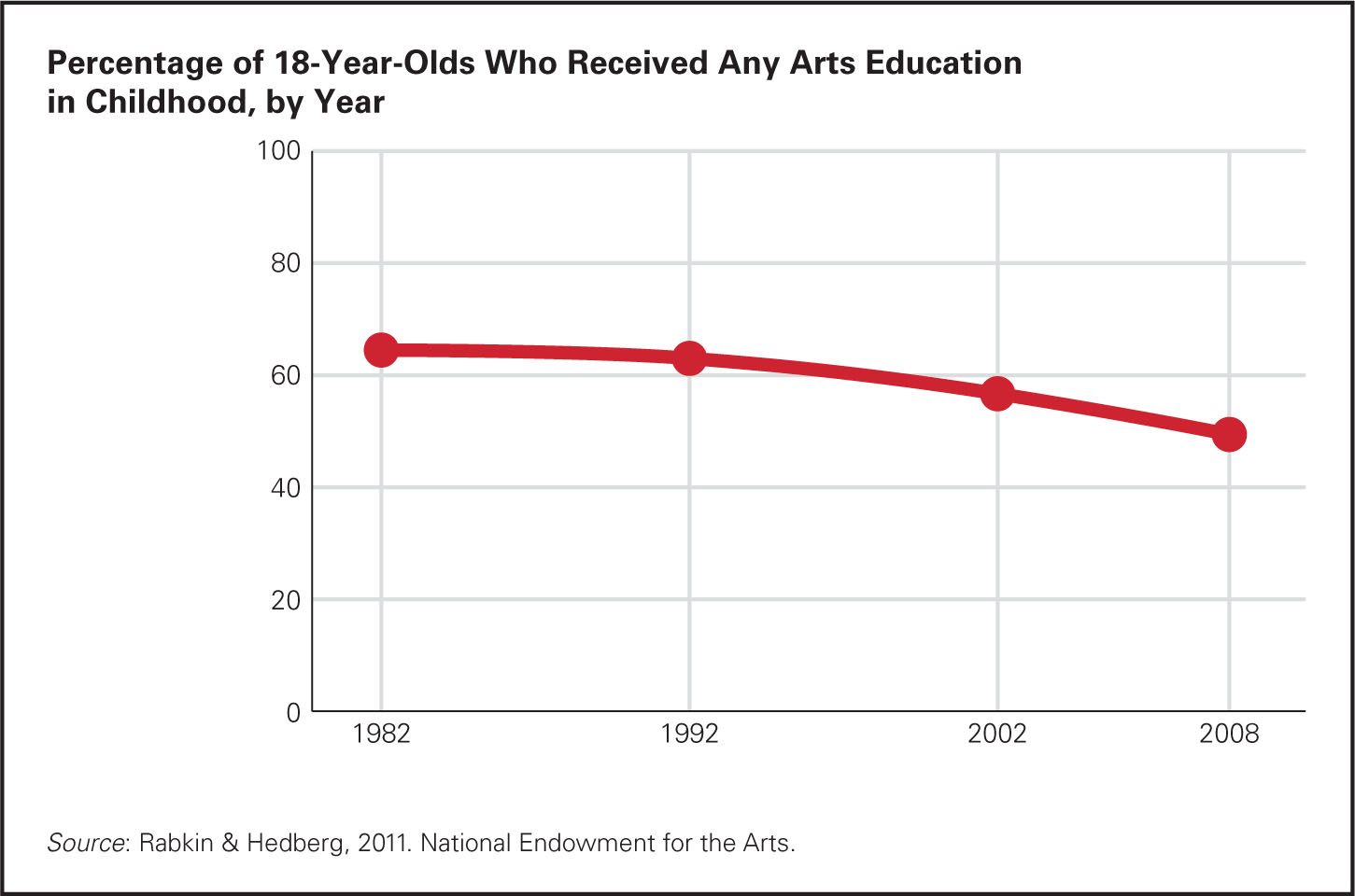

Geography, music, and art are essential in some places, not in others. Half of all U.S. 18-

354

| Math | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Norms and Expectations | |

|

4- |

|

|

| 6 years |

|

|

| 8 years |

|

|

| 10 years |

|

|

| 12 years |

|

|

| Math learning depends heavily on direct instruction and repeated practice, which means that some children advance more quickly than others. This list is only a rough guide, meant to illustrate the importance of sequence. | ||

| Reading | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Norms and Expectations | |

|

4- |

|

|

|

6- |

|

|

| 8 years |

|

|

|

9- |

|

|

| 11- |

|

|

| 13 + years |

|

|

| Reading is a complex mix of skills, dependent on brain maturation, education, and culture. The sequence given here is approximate; it should not be taken as a standard to measure any particular child. | ||

355

© OLIVIER CIRENDINI/LONELY PLANET/GETTY IMAGES

Educational practices may differ even between nations that are geographically and culturally close. For example, the average child in a primary school in Germany spends three times as much school time studying science as does the average child across the border, in the Netherlands (Snyder & Dillow, 2010).

hidden curriculum The unofficial, unstated, or implicit rules and priorities that influence the academic curriculum and every other aspect of learning in a school.

Differences between one nation and another, and, in the United States, between one school and another, are notable in aspects of the hidden curriculum, which includes implicit values and assumptions evident in course selection, schedules, tracking, teacher characteristics, discipline, teaching methods, sports competition, student government, extracurricular activities, and so on.

Whether students should be quiet or talkative in the classroom is part of the hidden curriculum, taught from kindergarten on. I realized this particular hidden curriculum difference when I taught at the United Nations high school. One student, newly arrived from India, never spoke in class so I called on him. He immediately stood up to answer—

More generally, if teachers’ gender, ethnicity, or economic background is unlike that of the students, children may conclude that education is irrelevant for them. If the school has gifted classes, the hidden message may be that most students are not very capable.

The physical setting of the school also sends a message. Some schools have spacious classrooms, wide hallways, and large, grassy playgrounds, others have cramped, poorly equipped rooms and cement play yards. In some nations, school is held outdoors, with no chairs, desks, or books, and sessions are canceled when it rains. What does that tell the students?

Observation Quiz What three differences do you see between recess in New York City (left) and Santa Rosa, California (right)?

Answer to Observation Quiz: The most obvious is the play equipment, but there are two others that make some New York children eager for recess to end. Did you notice the concrete play surface and the winter jackets?

© CHRISTOPHER CHUNG/ZUMAPRESS/CORBIS

356

International Testing

Over the past two decades, more than 50 nations have participated in at least one massive international test of educational achievement. Longitudinal data reveal that, if achievement rises, the national economy advances with it; this sequence seems causal, not merely correlational (Hanushek & Woessmann, 2009). Apparently, better-

Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) An international assessment of the math and science skills of fourth-

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) Inaugurated in 2001, a planned five-

Science and math achievement are tested in the Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS). The main test of reading is the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). These tests are given every few years, with East Asian nations usually ranking at the top and the United States’ rank rising, but it is still not as high as many other nations (see Tables 12.2 and 12.3). Most developing nations do not give these tests, but when they do, their scores are low.

After a wholesale reform of the educational system, Finland’s scores increased dramatically from about 1990 to 2001 (Sahlberg, 2011). Changes occurred over several years, from the abolishment of ability grouping in 1985 to curriculum reform in 1994 that encouraged collaboration and active learning. Strict requirements for becoming a teacher may be key. Only the top 3 percent of high school graduates are admitted to teachers’ colleges, where they receive five years of free education, including a master’s degree in education theory and practice.

| Rank* | Country | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Singapore | 606 |

| 2. | Korea | 605 |

| 3. | Hong Kong | 602 |

| 4. | Chinese Taipei | 591 |

| 5. | Japan | 585 |

| 6. | N. Ireland | 562 |

| 7 | Belgium | 549 |

| 8. | Finland | 545 |

| 9. | England | 542 |

| 10. | Russia | 542 |

| 11. | United States | 541 |

| 12. | Netherlands | 540 |

| Canada (Quebec) | 533 | |

| Germany | 528 | |

| Canada (Ontario) | 518 | |

| Australia | 516 | |

| Italy | 508 | |

| Sweden | 504 | |

| New Zealand | 486 | |

| Iran | 431 | |

| Yemen | 248 | |

| *The top 12 groups are listed in order, but after that, not all the jurisdictions that took the test are listed. Some nations have improved over the past 15 years (notably, Hong Kong, England) and some have declined (Austria, Netherlands), but most continue about where they have always been. | ||

| Source: Provasnik et al., 2012; TIMSS 2011 International Mathematics Report. | ||

| Country | Score |

|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 571 |

| Russia | 568 |

| Finland | 568 |

| Singapore | 567 |

| N. Ireland | 558 |

| United States | 556 |

| Denmark | 554 |

| Chinese Taipei | 553 |

| Ireland | 552 |

| England | 552 |

| Canada | 548 |

| Italy | 541 |

| Germany | 541 |

| Israel | 541 |

| New Zealand | 531 |

| Australia | 527 |

| Poland | 526 |

| France | 520 |

| Spain | 513 |

| Iran | 457 |

| Colombia | 448 |

| Indonesia | 428 |

| Morocco | 310 |

| Source: Adapted from Mullis et al., 2012. | |

357

Finnish teachers are also granted more autonomy within their classrooms than is typical in other systems, and since the 1990s they have time and encouragement to work with colleagues (Sahlberg, 2011). Buildings are designed to foster collaboration, with comfortable teacher’s lounges in place (Sparks, 2012), reflecting a hidden curriculum.

Respect for teaching might be the reason for Finland’s success, or perhaps something more basic regarding Finland’s size, population, culture, or history may be responsible. Or it may come from considering every child to have strengths and weaknesses: Few are designated as having special needs because all are given individualized attention.

International test results may be related to educational approaches in various nations. TIMSS experts videotaped 231 math classes in three nations—

By contrast, the Japanese teachers were excited about math instruction, working collaboratively and structuring lessons so that the children developed proofs and alternative solutions, both alone and in groups. Teachers used social interaction and followed an orderly sequence (building lessons on previous knowledge). Such teaching reflected all three theories of cognition: problem-

Problems with International Benchmarks

Elaborate and extensive measures are in place to make the PIRLS and the TIMSS valid. For instance, test items are designed to be fair and culture-

The tests are far from perfect, however. Designing test items that are equally challenging to all students is impossible. Should fourth-

Al wanted to find out how much his cat weighed. He weighed himself and noted that the scale read 57 kg. He then stepped on the scale holding his cat and found that it read 62 kg. What was the weight of the cat in kilograms?

Answer:_________kilograms

This problem involves simple subtraction. Yet, 40 percent of U.S. fourth-

358

In the United States

Although some national tests indicate improvements in U.S. children’s academic performance, when U.S. children are compared with children in other nations, not much has changed in reading or math scores in the past two decades. A particular concern is that a child’s achievement seems to be more influenced by income and ethnicity in the United States than in other nations, some of which have more diversity and more immigrants than the United States.

Also in the United States, although many educators and political leaders have attempted to eradicate performance disparities linked to a child’s background, the gap between fourth-

National Standards

No Child Left Behind Act A U.S. law enacted in 2001 that was intended to increase accountability in education by requiring states to qualify for federal educational funding by administering standardized tests to measure school achievement.

International comparisons and disparities within the United States led to passage of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001 (NCLB), a federal law promoting high national standards for public schools. One controversial aspect of the law is its requirement of frequent testing to measure whether standards are being met. Low-

Most people agree with the NCLB goals (accountability and higher achievement) but not with the strategies that must be used (Frey et al., 2012). NCLB troubles those who value the arts, social studies, or physical education because those subjects are often squeezed out when reading and math achievement is the priority (Dee et al., 2013). States have been granted substantial power of implementation, teacher preparation has increased but class size has not decreased, and the tests, and testing, remain controversial (Frey et al., 2012; Dee et al., 2013).

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) An ongoing and nationally representative measure of U.S. children’s achievement in reading, mathematics, and other subjects over time; nicknamed “the Nation’s Report Card.”

Federally sponsored tests called the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) measure achievement in reading, mathematics, and other subjects. Many critics believe that the NAEP is better than state tests (Applegate et al., 2009), basing their conclusion on the fact that the NAEP labels fewer children proficient than do state tests.

Disagreement about state tests and standards led the governors of all 50 states to designate a group of experts who developed a Common Core of standards, finalized in 2010, for use nationwide. The standards, higher than most state standards, are quite explicit, with half a dozen or more specific expectations for achievement in each subject for each grade. (Table 12.4 provides a sample of the specific standards.) As of 2013, forty-

The issue of how best to teach children to learn what they need, and what exactly that learning is, continues to be controversial in almost every nation.

359

| Grade | Reading and Writing | Math |

|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten | Pronounce the primary sound for each consonant | Know number names and the count sequence |

| First | Decode regularly spelled one- |

Relate counting to addition and subtraction (e.g., by counting 2 more to add 2) |

| Second | Decode words with common prefixes and suffixes | Measure the length of an object twice, using different units of length for the two measurements; describe how the two measurements relate to the size of the unit chosen |

| Third | Decode multisyllabic words | Understand division as an unknown- |

| Fourth | Use combined knowledge of all letter- |

Apply and extend previous understandings of multiplication to multiply a fraction by a whole number |

| Fifth | With guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach | Graph points on the coordinate plane to solve real- |

| Source: National Governors Association, 2010. | ||

Learning a Second Language

One example of such a controversy involves determining when, how, to whom, and whether schools should provide second-

In the United States, less than 5 percent of children under age 11 study a language other than English in school (Robelen, 2011). (In secondary school, almost every U.S. student takes a year or two of a language other than English, but studies of brain maturation suggest that this is too late for efficient language learning.)

Some U.S. educators note that almost every child speaks two languages by age 10 in Canada and most nations of Europe, where children are taught two languages throughout middle childhood. African children who are talented and fortunate enough to reach high school often speak three languages. The implications of this for U.S. language instruction are often ignored because of debates about immigration and globalization. Instead of trying to teach English-

immersion A strategy in which instruction in all school subjects occurs in the second (usually the majority) language that a child is learning.

bilingual schooling A strategy in which school subjects are taught in both the learner’s original language and the second (majority) language.

ESL (English as a Second Language) A U.S. approach to teaching English that gathers all the non-

Teaching approaches range from immersion, in which instruction occurs entirely in the new language, to the opposite, in which children are taught in their first language until the second language can be taught as a “foreign” tongue (a strategy rare in the United States but common elsewhere). Between these extremes lies bilingual schooling, with instruction in two languages, and ESL (English as a second language), with all non-

Methods for teaching a second language sometimes succeed and sometimes fail, with the research not yet clear as to which approach is best (Gandara & Rum-

360

Children and parents born outside the United States may not be accustomed to the teaching norms: For instance, should students be quiet or vocal? Should students work in groups or independently?

Many immigrants to the United States are raised in families in which survival depended on cooperation, and thus the competition and individuality within U.S. classrooms are disconcerting. At the same time, they often greatly respect education and teachers, so they are aghast if a student refuses to do homework or talks back to a teacher. To further complicate matters, generalities (including those just described) about immigrants and cultures may be stereotypes. For instance, although the political rhetoric sometimes implies that all U.S. immigrant children are from Mexico, many Latino immigrants are not Mexican, and many immigrants are not Latino. Although immigrants from Latin America account for more than half of the foreign-

Further, differences are vast within every group. Asian immigrants to the United States are from China, India, and many other Asian nations—

Cognitive research leaves no doubt that school-

Who Determines Educational Practice?

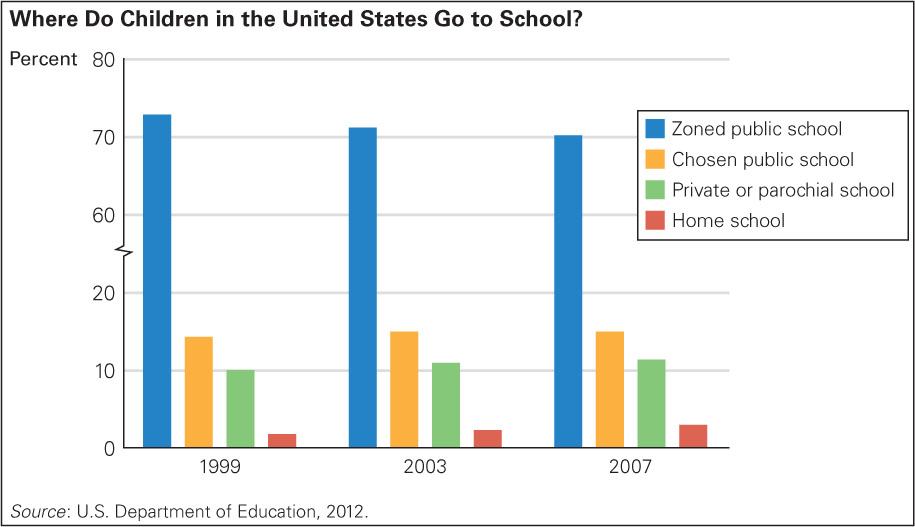

An underlying issue for almost any national or international educational dispute is the role of parents. In most nations, matters regarding public education—

In contrast, local U.S. jurisdictions provide most of the funds and guidelines. Parents affect education by talking to their child’s teacher, by parent–

361

Choices and Complications

charter school A public school with its own set of standards that is funded and licensed by the state or local district in which it is located.

Charter schools are public schools funded and licensed by states or local districts. Typically, they also have private money and sponsors. They are exempt from some regulations, especially those negotiated by unions, and they have some control over admissions and expulsions. For that reason, they often are more ethnically segregated and enroll fewer children with special needs. On average, teachers are younger and work longer hours, and school size is smaller than in traditional public schools.

Some charter schools are remarkably successful; others are not (Peyser, 2011). A major criticism is that not every child who enters a charter school stays to graduate; one scholar reports that “the dropout rate for African American males is shocking” (Miron, quoted in Zehr, 2011, p. 1). Overall, children and teachers leave charter schools more often than they leave regular public schools, a disturbing statistic. However, the explanation may be that because teachers and parents actively choose charter schools, such people may be more selective, or more critical by nature, and thus more willing to leave a school if their expectations are not met.

private school A school funded by tuition charges, endowments, and often religious or other nonprofit sponsors.

Private schools are funded by tuition, endowments, and church sponsors. Traditionally in the United States, most private schools were parochial (church related), organized by the Catholic Church to teach religion and to resist the anti-

voucher Public subsidy for tuition payment at a nonpublic school. Vouchers vary a great deal from place to place, not only in amount and availability but also in restrictions as to who gets them and what schools accept them.

To solve that problem, some U.S. jurisdictions issue vouchers, money that parents can use to pay some or all of the tuition at a private school, including a church-

home schooling Education in which children are taught at home, usually by their parents.

Home schooling occurs when parents avoid both public and private schools by educating their children at home. This solution is becoming more common, but only about 1 child in 35 (more girls than boys, more preadolescents than teenagers) is home-

The major problem with home schooling is not academic (some mothers are conscientious teachers and some home-

Especially for School Administrators Children who wear uniforms in school tend to score higher on reading tests. Why?

Response for School Administrators: The relationship reflects correlation, not causation. Wearing uniforms is more common when the culture of the school emphasizes achievement and study, with strict discipline in class and a policy of expelling disruptive students.

The underlying problem with all these options is that people disagree about the best education for a 6-

362

Mixed evidence comes from nations where children score high on international tests. Sometimes they have large student-

Who should decide what children should learn and how? Every developmental theory can lead to suggestions for teaching and learning (Farrar & Al-

SUMMING UP

Societies throughout the world recognize that school-

363

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Education in Middle Childhood Around the World

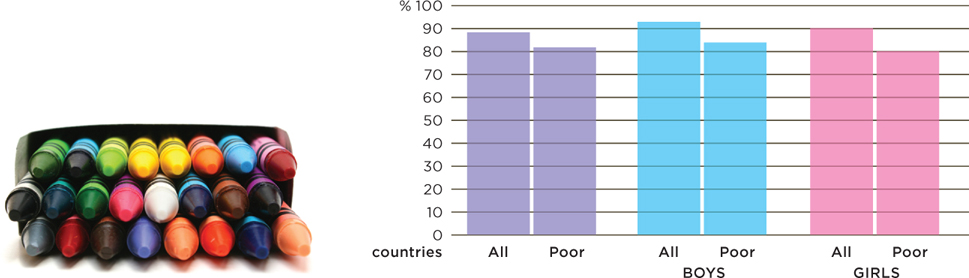

Only a decade ago, gender differences in education around the world were stark, with far fewer girls in school than boys. Now girls have almost caught up, but recent data finds that the best predictor of childhood health is an educated mother. Many of today’s children suffer from decades of inequality.

WORLDWIDE PRIMARY SCHOOL ENROLLMENT, 2011

Enrollments in elementary school are increasing around the world, but poor countries still lag behind more wealthy ones and in all countries, more boys attend school than boys.

SOURCE: THE WORLD BANK, 2013

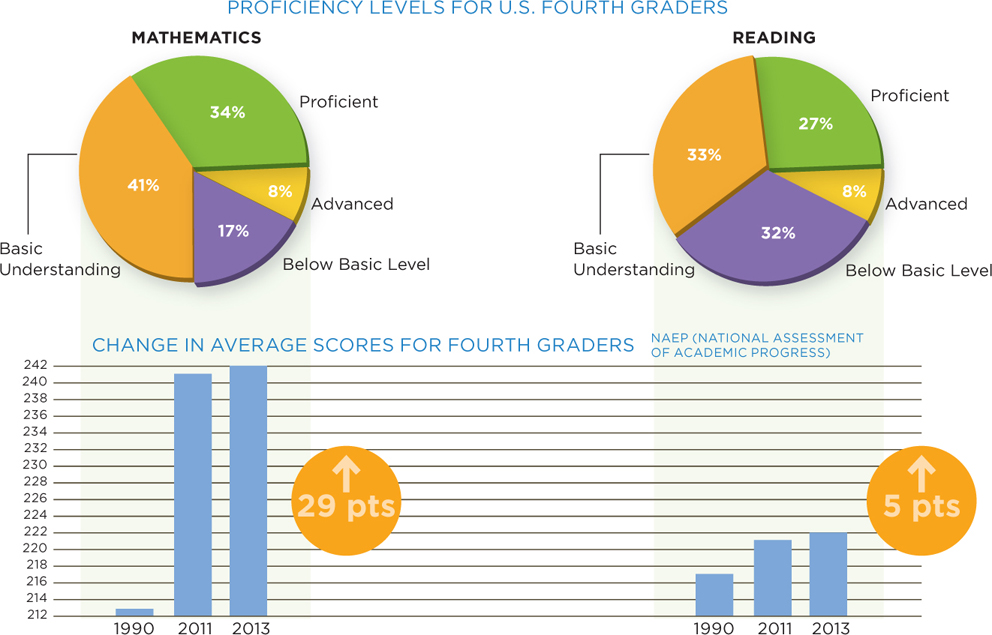

HOW ARE U.S. FOURTH GRADERS DOING?

Primary school enrollment is high in the United States, but not every student is learning. While numbers are improving, less than half of fourth graders are proficient in math and reading.

SOURCES & CREDITS LISTED ON P. SC-

SOURCE: NAEP 2013, FIGURE 1.

364