13.4 Children’s Moral Values

The origins of morality are debatable (see Chapter 10), but there is no doubt that middle childhood is prime time for moral development. These are:

years of eager, lively searching on the part of children…as they try to understand things, to figure them out, but also to weigh the rights and wrongs…. This is the time for growth of the moral imagination, fueled constantly by the willingness, the eagerness of children to put themselves in the shoes of others.

[Coles, 1997, p. 99]

Many forces drive children’s growing interest in moral issues. Three of them are (1) child culture, (2) personal experience, and (3) empathy. As already explained, the culture of children includes moral values, such as loyalty to friends and keeping secrets. Personal experiences also matter.

For example, students in multiethnic schools are better able to use morality to combat prejudice than students in more ethnically homogeneous schools (Killen et al., 2006). For all children, empathy increases in middle childhood because children become more socially perceptive.

This increasing perception can backfire, however. One example was just described: Bullies become adept at picking victims (Veenstra et al., 2010). An increase in social understanding makes noticing and defending rejected children possible, but in a social context that allows bullying, bystanders may decide to be self-

Children who are slow to develop theory of mind—

Moral Reasoning

Much of the developmental research on children’s moral thinking began with Piaget’s descriptions of the rules used by children as they play (Piaget, 1932/1997). This work led to a famous description of cognitive stages of morality (Kohlberg, 1963).

390

Kohlberg’s Levels of Moral Thought

Lawrence Kohlberg described three levels of moral reasoning and two stages at each level (see Table 13.3), with parallels to Piaget’s stages of cognition.

Level I: Preconventional Moral ReasoningThe goal is to get rewards and avoid punishments; this is a self-

|

Level II: Conventional Moral ReasoningEmphasis on social rules; this is a family, community, and cultural level.

|

Level III: Postconventional Moral ReasoningEmphasis is placed on moral principles; this level is centered on ideals.

|

- Preconventional moral reasoning is similar to preoperational thought in that it is egocentric, with children most interested in their personal pleasure or avoiding punishment.

preconventional moral reasoning Kohlberg’s first level of moral reasoning, emphasizing rewards and punishments.

- Conventional moral reasoning parallels concrete operational thought in that it relates to current, observable practices: Children watch what their parents, teachers, and friends do, and try to follow suit.

conventional moral reasoning Kohlberg’s second level of moral reasoning, emphasizing social rules.

- Postconventional moral reasoning is similar to formal operational thought because it uses abstractions, going beyond what is concretely observed, willing to question “what is” in order to decide “what should be.”

postconventional moral reasoning Kohlberg’s third level of moral reasoning, emphasizing moral principles.

According to Kohlberg, intellectual maturation advances moral thinking. During middle childhood, children’s answers shift from being primarily preconventional to being more conventional: Concrete thought and peer experiences help children move past the first two stages (level I) to the next two (level II). Postconventional reasoning is not usually present until adolescence or adulthood, if then.

Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to school-

391

Heinz went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said “no.” The husband got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that? Why?

[Kohlberg, 1963, p. 19]

The crucial element in Kohlberg’s assessment of moral stages is not what a person answers but the reasons given.

For instance, suppose someone says that Heinz should steal the drugs. The reason could be that Heinz needs his wife to care for him (preconventional), or that people will blame him if he lets his wife die (conventional), or that a human life is more important than obeying a law (postconventional).

Or suppose someone says Heinz should not steal. The reason could be that he will go to jail (preconventional) or that business owners will blame him (conventional) or that for a community to function, no one should take another person’s livelihood (postconventional).

Criticisms of Kohlberg

Kohlberg has been criticized for not appreciating cultural or gender differences. For example, loyalty to family overrides any other value in some cultures, so some people might avoid postconventional actions that hurt their family. Also, Kohlberg’s original participants were all boys, which may have led him to discount female values of nurturance and relationships (Gilligan, 1982). Overall, Kohlberg seemed to value abstract principles more than individual needs, but caring for individuals may be no less moral than impartial justice (Sherblom, 2008).

Furthermore, Kohlberg did not seem to recognize that although children’s morality differs from that of adults, they may be quite moral. School-

In one respect, however, Kohlberg was undeniably correct. He was right in noting that children use their intellectual abilities to justify their moral actions. In one experiment, children aged 8 to 18 were grouped with two others about the same age, were allotted some money, and were asked to decide how much to share with another trio of children.

There were no age trends in the actual decisions: Some groups chose to share equally; other groups were more selfish. However, there were age differences in the reasons. Older children suggested more complex rationalizations for their choices, both selfish and altruistic (Gummerum et al., 2008).

What Children Value

Many lines of research have shown that children develop their own morality, guided by peers, parents, and culture (Killen & Smetana, 2014). Some prosocial values are evident in early childhood. Among these values are caring for close family members, cooperating with other children, and not hurting anyone intentionally. Even very young children think stealing is wrong.

As children become more aware of themselves and others in middle childhood, they realize that one person’s values may conflict with another’s. Concrete operational cognition, which gives children the ability to understand and to use logic, propels them to think about morality and to try to behave ethically (Turiel, 2006). As part of growing up, children become conscious of immorality in their peers (Abrams et al., 2008) and, later on, in their parents, themselves, and their culture.

392

Adults Versus Peers

When child culture conflicts with adult morality, children often align themselves with peers. A child might lie to protect a friend, for instance. Friendship itself has a hostile side: Many close friends resist other children who want to join in (Rubin et al., 2013).

The conflict between the morality of children and that of adults is evident in the value that children place on education. Adults usually prize school, but children may encourage one another to play hooky, cheat on tests, or drop out. Peer values may outweigh adult values. Consider another comment from Paul:

I try not to get influenced too much, pulled into what I don’t want to be into. But mostly, it’s hard. You don’t want people to be saying you’re stupid. “Why do you want to go to school and get a job?…Drop out.”

[quoted in Nieto, 2000, p. 252]

Not surprisingly, Paul later left school.

Three common moral imperatives among 6-

- Protect your friends.

- Don’t tell adults what is happening.

- Conform to peer standards of dress, talk, behavior.

These three can explain both apparent boredom and overt defiance, as well as standards of dress that mystify adults (such as jeans so loose that they fall off or so tight that they impede digestion—

Before criticizing children for conforming to other children, notice adults. For example, many Americans homeowners spend time and money growing lawns, which need fertilizer, watering, and mowing, not because they enjoy it but because all the neighbors have lawns. At least that is the opinion of one blogger who wrote that lawns are “Wasteful, Unquestioned Totems of Conformity.” (Godlike Productions, 2012).

Fortunately, peers during adulthood as well as childhood help one another develop morals. Research finds that children are better at stopping bullying than adults are, because children sometimes defend the victim and isolate the bully. Since bullies tend to be low on empathy, they need peers to teach them that their actions are not admired (many bullies believe people admire their aggression). During middle childhood, morality can be scaffolded just as cognitive skills are, with mentors—

Developing Moral Values

Throughout middle childhood, moral judgment becomes more comprehensive, taking into account psychological as well as physical harm, intentions as well as consequences. For example, when 5-

393

A detailed examination of the effect of peers on morality began with an update on one of Piaget’s moral issues: whether punishment should seek retribution (hurting the transgressor) or restitution (restoring what was lost). Piaget found that children advance from retribution to restitution between ages 8 and 10 (Piaget, 1932).

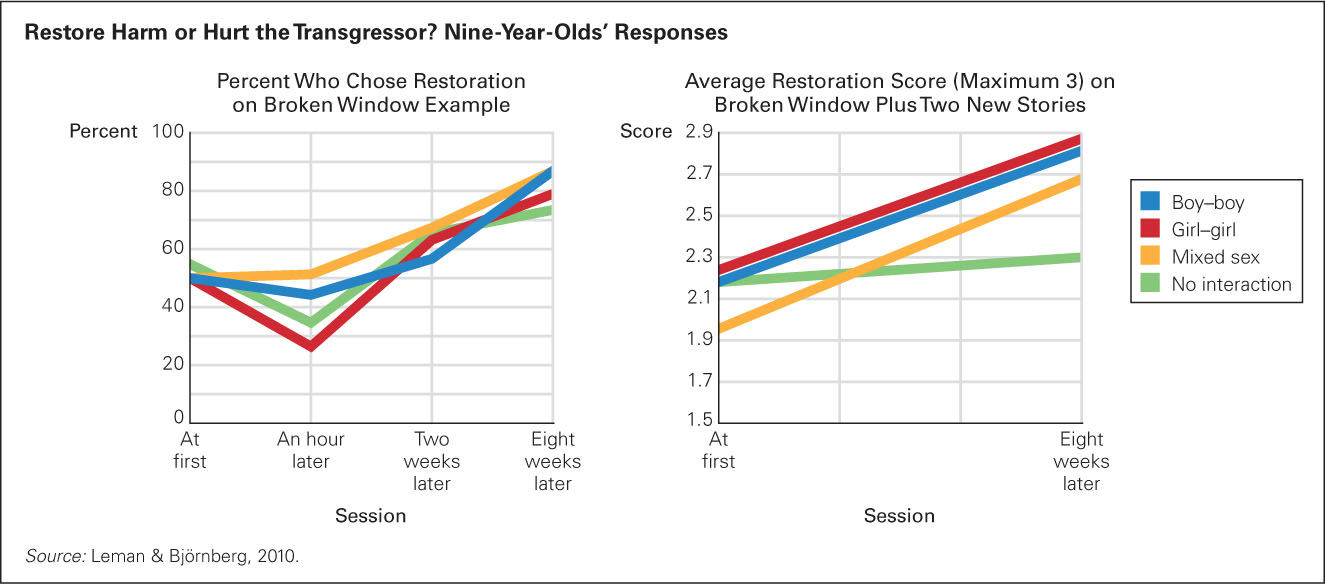

To learn how this occurs, researchers asked 133 9-

Late one afternoon there was a boy who was playing with a ball on his own in the garden. His dad saw him playing with it and asked him not to play with it so near the house because it might break a window. The boy didn’t really listen to his dad, and carried on playing near the house. Then suddenly, the ball bounced up high and broke the window in the boy’s room. His dad heard the noise and came to see what had happened. The father wonders what would be the fairest way to punish the boy. He thinks of two punishments. The first is to say: “Now, you didn’t do as I asked. You will have to pay for the window to be mended, and I am going to take the money from your pocket money.” The second is to say: “Now, you didn’t do as I asked. As a punishment you have to go to your room and stay there for the rest of the evening.” Which of these punishments do you think is the fairest?

[Leman & Björnberg, 2010, p. 962]

The children were split almost equally in their answers. Then 24 pairs were formed of children who had opposite views. Each pair was asked to discuss the issue, trying to reach agreement. (The other children did not discuss it). Six pairs were boy–

The conversations typically took only five minutes, and the retribution side was more often chosen—

394

The main conclusion from this study was that “conversation on a topic may stimulate a process of individual reflection that triggers developmental advances” (Leman & Björnberg, 2010, p. 969). Parents and teachers take note: Raising moral issues, and letting children talk about them, may advance morality—

Think again about the opening anecdote for this chapter (killing zombies) or the previous chapter (piercing ears). In both cases, the parent used age as a criterion, and in both cases the child rejected that argument. A better argument might raise a higher standard; in the first example, for instance, that killing is never justified. The child might disagree, but such conversations might help the child think more deeply about moral values, as happened in this experiment. That deeper thought might protect the child during adolescence, when life-

SUMMING UP

Moral issues are of great interest to children in middle childhood, who are affected by their cultures, by their parents, and particularly by their peers. Kohlberg’s stages of moral thought parallel Piaget’s stages of development, suggesting that the highest level of morality transcends the norms of any particular nation. Kohlberg has been criticized for not having a multicultural understanding, but it is true that moral judgment advances from ages 6 to 11. Children develop moral standards that they try to follow, although these may differ from adult morals, in part because children’s morality includes loyalty to peers. Maturation, reflection, and discussion all foster moral development.

395