15.1 Logic and Self

Brain maturation, additional years of schooling, moral challenges, increased independence, and intense conversations all occur between the ages of 11 and 18. These aspects of the adolescent’s development propel impressive cognitive growth, as teenagers move from egocentrism to abstract logic.

Egocentrism

During puberty, young people center on themselves, in part because maturation of the brain heightens self-

adolescent egocentrism A characteristic of adolescent thinking that leads young people (ages 10 to 13) to focus on themselves to the exclusion of others.

Adolescent egocentrism—thinking intensely about themselves and about what others think of them—

In egocentrism, adolescents regard themselves as much more unique, special, and admired or disliked than they actually are. For example, few adolescent girls are attracted to boys with pimples and braces, but Edgar was so eager to be recognized as growing up that he did not realize this, according to his older sister:

Now in the 8th grade, Edgar has this idea that all the girls are looking at him in school. He got his first pimple about three months ago. I told him to wash it with my face soap but he refused, saying, “Not until I go to school to show it off.” He called the dentist, begging him to approve his braces now instead of waiting for a year. The perfect gifts for him have changed from action figures to a bottle of cologne, a chain, and a fitted baseball hat like the rappers wear.

[adapted from Eva, personal communication]

Egocentrism leads adolescents to interpret everyone else’s behavior as if it were a judgment on them. A stranger’s frown or a teacher’s critique can make a teenager conclude that “No one likes me” and then deduce that “I am unlovable” or even “I can’t leave the house.” More positive casual reactions—

Acute self-

Fables

personal fable An aspect of adolescent egocentrism characterized by an adolescent’s belief that his or her thoughts, feelings, and experiences are unique, more wonderful, or more awful than anyone else’s.

invincibility fable An adolescent’s egocentric conviction that he or she cannot be overcome or even harmed by anything that might defeat a normal mortal, such as unprotected sex, drug abuse, or highspeed driving.

The personal fable is the belief that one is unique, destined to have a heroic, fabled, even legendary life. Some 12-

In every nation, most volunteers for military service—

431

The Imaginary Audience

imaginary audience The other people who, in an adolescent’s egocentric belief, are watching and taking note of his or her appearance, ideas, and behavior. This belief makes many teenagers very self-

Egocentrism creates an imaginary audience in the minds of many adolescents. They believe they are at center stage, with all eyes on them, and they imagine how others might react to their appearance and behavior.

One woman remembers:

When I was 14 and in the 8th grade, I received an award at the end-

[Somerville, 2013, p. 212]

This woman went on to become an expert on the adolescent brain; she knew from personal experience that “adolescents are hyperaware of other’s evaluations and feel they are under constant scrutiny by an imaginary audience” (Somerville, 2013, p. 124).

Egocentrism Reassessed

Egocentrism is sometimes blamed for every foolish action an adolescent takes (Leather, 2009). However, that is too simple a generalization. First, some adolescents do not feel they are invincible at all; instead they have exaggerated perceptions of risks (Mills et al., 2008). Neurological studies show that in some ways adolescents are fearless. Yet, particularly regarding social disapproval, adolescents are more anxious than people of any other age (Pattwell et al., 2013).

Second, egocentrism may be protective when “an individual enters into a new environmental context or dramatically new life situation” (Schwartz et al., 2008, p. 447) because being sensitive to social cues speeds adjustment. The egocentrism of adolescents brings psychic benefits as well as dangers (Martin & Sokol, 2011).

Formal Operational Thought

formal operational thought In Piaget’s theory, the fourth and final stage of cognitive development, characterized by more systematic logical thinking and by the ability to understand and systematically manipulate abstract concepts.

Piaget described a shift to formal operational thought, as adolescents move past concrete operational thinking and consider abstractions, including “assumptions that have no necessary relation to reality” (Piaget, 1972, p. 148).

One way to distinguish formal from concrete thinking is to compare curricula in primary school and high school. Here are three examples:

- Math. Younger children multiply real numbers, such as 4 × 3 × 8; adolescents can multiply unreal numbers, such as (2x)(3y) or even (25xy2)(−3zy3).

- Social studies. Younger children study other cultures by considering daily life—

drinking goat’s milk or building an igloo, for instance. Adolescents can consider the effect of “gross national product” and “fertility rate” on global politics. - Science. Younger students water plants; adolescents test H2O in the lab.

Each of these examples shows that teachers realize what their students can understand.

Piaget’s Experiments

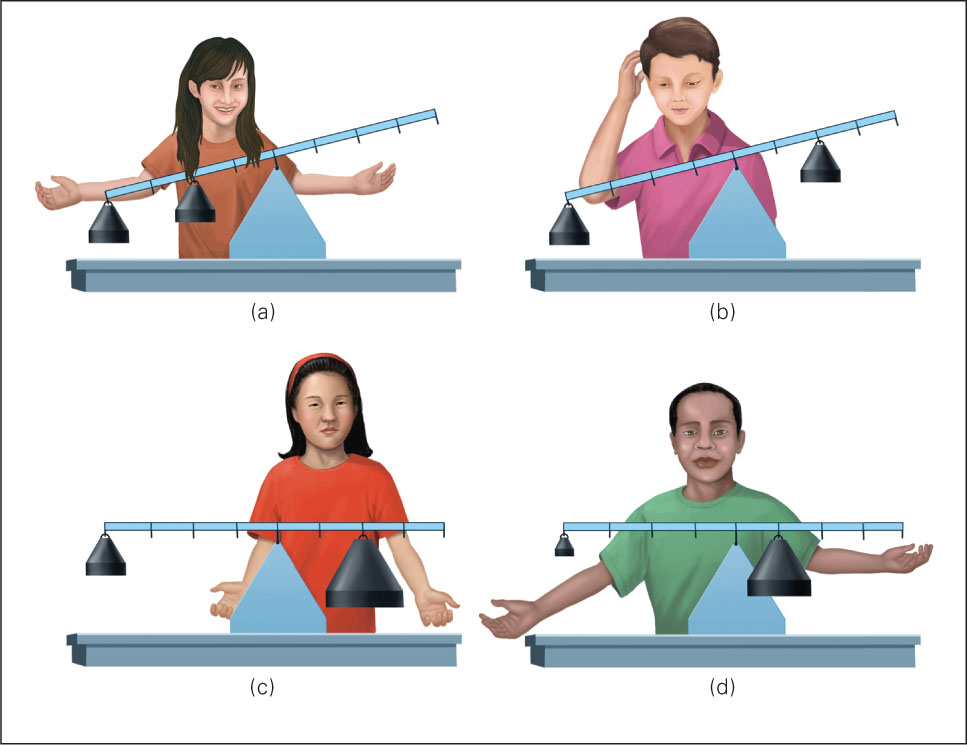

Piaget and his colleagues devised a number of tasks to assess formal operational thought (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958); “in contrast to concrete operational children, formal operational adolescents imagine all possible determinants … [and] systematically vary the factors one by one, observe the results correctly, keep track of the results, and draw the appropriate conclusions” (P. H. Miller, 2011, p. 57).

432

One of their experiments (diagrammed in Figure 15.1) required balancing a scale by hooking weights onto the scale’s arms. To master this task, a person must realize the reciprocal interaction between distance and the weights’ heaviness. Therefore, a heavy weight close to the center can be counterbalanced with a light weight far from the center on the other side.

Balancing was not understood by the 3-

Hypothetical-Deductive Reasoning

One hallmark of formal operational thought is the capacity to think of possibility, not just reality. “Here and now” is only one of many possibilities, including “there and then,” “long, long ago,” “not yet,” and “never.” As Piaget said:

The adolescent … thinks beyond the present and forms theories about everything, delighting especially in considerations of that which is not …

[Piaget, 1972, p. 148]

hypothetical thought Reasoning that includes propositions and possibilities that may not reflect reality.

Adolescents are therefore primed to engage in hypothetical thought, reasoning about if–

If all mammals can walk,

And whales are mammals,

Can whales walk?

Children answer “No!” They know that whales swim, not walk; the logic escapes them. Some adolescents answer “Yes.” They understand the concept of if, and therefore the counterfactual phase “if all mammals.”

433

Possibility no longer appears merely as an extension of an empirical situation or of action actually performed. Instead, it is reality that is now secondary to possibility.

[Inhelder & Piaget, 1958, p. 251; emphasis in original]

Hypothetical thought transforms perceptions, but not necessarily for the better. Adolescents might criticize everything from their mother’s spaghetti (it’s not al dente) to the Gregorian calendar (it’s not the Chinese or Jewish one). They criticize what is because of their hypothetical thinking about what might be and their growing awareness that other families and cultures differ from their own. That complicates decision making when it comes to immediate, practical questions (Moshman, 2011).

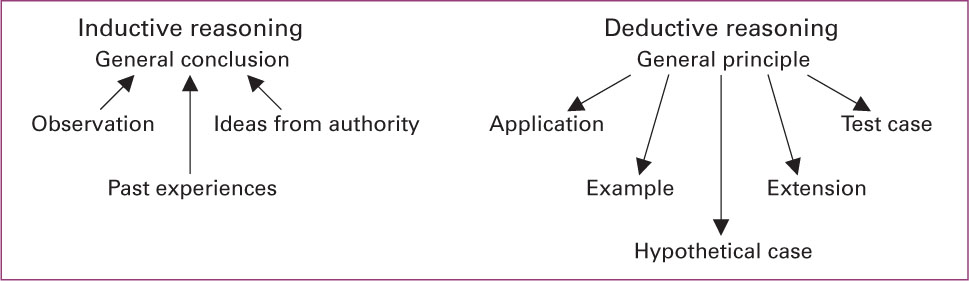

deductive reasoning Reasoning from a general statement, premise, or principle, through logical steps, to figure out (deduce) specifics. (Also called top-

inductive reasoning Reasoning from one or more specific experiences or facts to reach (induce) a general conclusion. (Also called bottom-

In developing the capacity to think hypothetically, by age 14 or so adolescents become capable of deductive reasoning, or top-

In essence, a child’s reasoning goes like this: “This creature waddles and quacks. Ducks waddle and quack. Therefore, this must be a duck.” This reasoning is inductive: It progresses from particulars (“waddles” and “quacks”) to a general conclusion (“a duck”). By contrast, deduction progresses from the general to the specific: “If it’s a duck, it will waddle and quack” (see Figure 15.2).

An example of the progress toward deductive reasoning comes from how children, adolescents, and adults change in their understanding of the causes of racism. Even before adolescence, almost everyone is aware that racism exists—

Especially for Natural Scientists Some ideas that were once universally accepted, such as the belief that the sun moved around the Earth, have been disproved. Is it a failure of inductive or deductive reasoning that leads to false conclusions?

Response for Natural Scientists: Probably both. Our false assumptions are not logically tested because we do not realize that they might need testing.

This example arises from a study of adolescent agreement or disagreement with policies to remedy racial discrimination (Hughes & Bigler, 2011). Not surprisingly, most students of all ages in an interracial U.S. high school recognized disparities between African and European Americans and believed that racism was a major cause.

However, the age of the students made a difference. Among those who recognized marked inequalities, older adolescents (ages 16 to 17) more often supported systemic solutions (e.g., affirmative action and desegregation) than did younger adolescents (ages 14 to 15). Hughes and Bigler wrote: “during adolescence, cognitive development facilitates the understanding that discrimination exists at the social-

434

Logical Fallacies

Many cognitive scientists study how people of all ages sometimes think illogically. Such failures are apparent throughout adolescence (Albert & Steinberg, 2011), but there is one age-

sunk cost fallacy The mistaken belief that if money, time, or effort that cannot be recovered (a “sunk cost,” in economic terms) has already been invested in some endeavor, then more should be invested in an effort to reach the goal. Because of this fallacy, people spend money trying to fix a “lemon” of a car or send more troops to fight a losing battle.

One example is the sunk cost fallacy: the belief of people who have spent if money, time, or effort that cannot be recovered (a cost already “sunk”) that they must continue to pursue their goal because otherwise all previous effort in reaching that goal will be wasted (Cunha & Caldieraro, 2009). It is this fallacy that leads people to pour money into repairing a “lemon” of a car, remain in a class they are failing, stay in an abusive relationship, and so on.

base rate neglect A common fallacy in which a person ignores the overall frequency of some behavior or characteristic (called the base rate) in making a decision. For example, a person might bet on a “lucky” lottery number without considering the odds that that number will be selected.

Another common fallacy is base rate neglect (Kahneman, 2011), in which people ignore information about the frequency of a phenomenon. For example (cited by Kahneman, 2011, p. 151), if a stranger on the subway is reading the New York Times, which is more likely?

She does not have a college degree.

She has a Ph.D.

The answer is no college degree. Far more subway riders have no degree than have a Ph.D. (perhaps 50:1). But people tend to ignore that base rate, and instead conclude that a Ph.D. recipient is more likely to read the New York Times than someone without a degree. That is base rate neglect.

Egocentrism makes base rate neglect more likely and more personal. For instance, a teen might not wear a bicycle helmet, feeling invincible despite statistics, until a friend is brain-

Not only adolescents but also adults sometimes reason like concrete operational or even preoperational children. Logical fallacies occur at every age, and “No contemporary scholarly reviewer of research evidence endorses the emergence of a discrete new cognitive structure at adolescence that closely resembles … formal operations” (Kuhn & Franklin, 2006, p. 954). Nonetheless, something shifts in cognition after puberty: Piaget was correct when he concluded that most older adolescents can think differently than most children do.

SUMMING UP

Thinking reaches heightened self-

Piaget’s fourth and final stage of intelligence, called formal operational thought, begins in adolescence. He found that adolescents’ deductive logic and hypothetical reasoning improve. Other scholars note logical lapses at every age and much more variability in adolescent thought than Piaget’s description implies.