16.1 Identity

Psychosocial development during adolescence is often understood to be a search for a consistent understanding of oneself. Self-

458

identity versus role confusion Erikson’s term for the fifth stage of development, in which the person tries to figure out “Who am I?” but is confused as to which of many possible roles to adopt.

identity achievement Erikson’s term for the attainment of identity, or the point at which a person understands who he or she is as a unique individual, in accord with past experiences and future plans.

According to Erik Erikson, life’s fifth psychosocial crisis is identity versus role confusion: The complexities of finding one’s own identity are the primary task of adolescence (Erikson, 1968). He said this crisis is resolved with identity achievement, when adolescents have reconsidered the goals and values of their parents and culture, accepting some and discarding others, forging their own identity.

The result is neither wholesale rejection nor unquestioning acceptance of social norms (Côté, 2009). With their new autonomy, teenagers maintain continuity with the past so that they can move to the future. Each person must achieve his or her own identity. Simply adopting parental norms does not work, because the social context of each generation differs, and everyone has a unique combination of genes and alleles.

Not Yet Achieved

Erikson’s insights have inspired thousands of researchers. Notable among those he influenced was James Marcia, who described and measured four specific ways young people cope with the identity crisis: (1) role confusion, (2) foreclosure, (3) moratorium, and finally (4) identity achievement (Marcia, 1966).

Over the past half-

role confusion A situation in which an adolescent does not seem to know or care what his or her identity is. (Sometimes called identity or role diffusion.)

Role confusion is the opposite of identity achievement. It is characterized by lack of commitment to any goals or values. It is sometimes called identity diffusion to emphasize that some adolescents seem diffuse, unfocused, and unconcerned about their future (Phillips & Pittman, 2007).

Even usual social demands—

foreclosure Erikson’s term for premature identity formation, which occurs when an adolescent adopts parents’ or society’s roles and values wholesale, without questioning or analysis.

Identity foreclosure occurs when, in order to avoid the confusion of not knowing who they are, young people accept traditional roles and values (Marcia, 1966; Marcia et al., 1993). They might follow customs transmitted from their parents or culture, never exploring alternatives. Or they might foreclose on an oppositional, negative identity—the direct opposite of whatever their parents want—

moratorium An adolescent’s choice of a socially acceptable way to postpone making identity-

A more mature shelter is the moratorium, a Timeout that includes some exploration, either in breadth (trying many things) or in depth (following one path after a tentative, temporary commitment) (Meeus, 2011). In high school, a student might become focused on playing in a band, not expecting this to be a lifelong career; in the next stage, emerging adulthood, moratoria might lead to signing up for the army. Moriatoria are more common at age 19 than younger, because some maturity is required (Kroger et al., 2010).

Several aspects of the search for identity, especially sexual and vocational identity, have become more arduous than they were when Erikson described them, and establishing a personal identity is more difficult. Fifty years ago, the drive to become independent and autonomous was thought to be the “key normative psychosocial task of adolescence” (Zimmer-

459

Four Arenas of Identity Formation

Erikson (1968) highlighted four aspects of identity: religious, political, vocational, and sexual. Terminology and emphasis have changed for all four, as has timing. In fact, if an 18-

None of these four identity statuses occurs in social isolation: Parents and peers are influential, as detailed later in this chapter, and the ever-

Religious Identity

For most adolescents, their religious identity is similar to that of their parents and community. Few adolescents totally reject religion if they’ve grown up following a particular faith, especially if they have a good relationship with their parents (Kim-

Past parental practices influence adolescent religious identity, although some adolescents express that identity in ways that their parents did not anticipate: A Muslim girl might start to wear a headscarf, a Catholic boy might study for the priesthood, or a Baptist teenager might join a Pentecostal youth group, each surprising their less devout parents.

Such new practices are relatively minor, not evidence of a totally new religious identity. Almost no young Muslims convert to Judaism, and almost no teenage Baptists become Hindu—

JIM WEST/THE IMAGE WORKS

460

Political Identity

Parents also influence their children’s political identity. In the twenty-

A word here about political terrorism and religious extremism: Those under age 30 are often on the front lines of terrorism or are converts to groups that their elders consider cults. Fanatical political and religious movements have much in common—

However, adolescents are rarely drawn to these groups unless personal loneliness or family background (such as a parent’s death caused by an opposing group) compels them. It is myth that every teenager is potentially a suicide bomber or a willing martyr. The risk-

Vocational Identity

Vocational identity originally meant envisioning oneself as a worker in a particular occupation. Choosing a future career made sense for teenagers a century ago, when most girls became housewives and most boys became farmers, small businessmen, or factory workers. Those few in professions were generalists (doctors did family medicine, lawyers handled all kinds of cases, teachers taught all subjects).

Obviously, early vocational identity is no longer appropriate. No teenager can be expected to choose among the tens of thousands of careers; most adults change vocations (not just employers) many times. Vocational identity takes years to establish, and most jobs demand quite specific skills and knowledge that are best learned on the job.

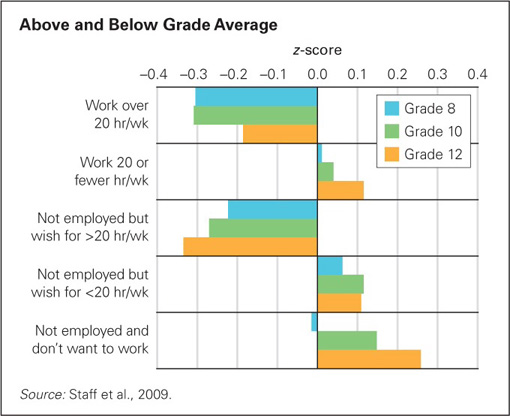

Although some adults hope that employment will keep teenagers out of trouble as they identify as workers, the opposite is more likely (Staff & Schulenberg, 2010). Adolescents who work more than 20 hours a week during the school year tend to quit school, fight with parents, smoke cigarettes, and hate their jobs—

Sexual Identity

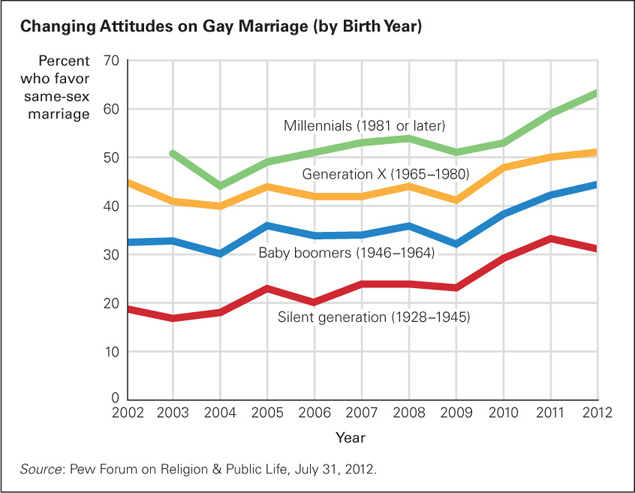

Achieving sexual identity is also a lifelong task, in part because norms of sexuality and attitudes about it keep changing (see Figure 16.2). Increasing numbers of young adults are single, gay, and cohabiting, providing teenagers with new role models and choices and thus making sexual identity more confusing.

461

A half-

gender identity A person’s acceptance of the roles and behaviors that society associates with the biological categories of male and female.

As you remember from Chapter 10, for social scientists sex and sexual refer to biological characteristics, whereas gender refers to cultural and social attributes that differentiate males and females. Erikson’s term sexual identity has been replaced by gender identity (Denny & Pittman, 2007), which refers primarily to a person’s self-

Gender roles once meant that only men were employed; they were breadwinners (good providers) and women were housewives (married to their houses). As women entered the labor market, gender roles expanded but were still apparent (nurse/doctor, secretary/businessman, pink collar/blue collar). That is changing—

What also has not changed is the adolescent’s experience of a strong sexual drive as hormone levels increase. As Erikson recognized, many are confused regarding when, how, and with whom to express those drives. Some adolescents foreclose by exaggerating male or female roles; others seek a moratorium by avoiding all sexual contact. If adolescents feel their gender identity is fragile, they are more likely to aspire to a gender-

462

SUMMING UP

Erikson’s fifth psychosocial crisis—

Specific aspects of identity—