16.2 Relationships with Adults

Adolescence is often characterized as a period of waning adult influence, when children distance themselves from their elders. This picture is not always accurate. Adult influence is less immediate but no less important.

Parents

The fact that parent—

Normally, conflict peaks in early adolescence, especially between mothers and daughters, usually in bickering—repeated, petty arguments (more nagging than fighting) about routine, day-

Unspoken concerns need to be aired so both generations better understand each other. Imagine a parent seeing dirty socks on the floor. The parent might think that is a deliberate mark of adolescent disrespect and therefore react angrily. But perhaps the adolescent was merely distracted, oblivious to the parent’s desire for a neat house. If so, then the parent could merely sigh and put the socks in laundry.

Some bickering may indicate a healthy family, since close relationships almost always include conflict. The parent-

463

You have already learned that authoritative parenting is usually best for children and that uninvolved parenting is worst. [Lifespan Link: Parenting styles were discussed in Chapter 10.] The same holds true in adolescence. Although teenagers sometimes say their parents are irrelevant, that is not true. Neglect is always destructive and authoritarian parenting can boomerang, resulting in children who lie, leave, or learn to deceive their parents.

Cultural Differences

Expectations vary by culture, as do justifications (Brown & Bakken, 2011). For example, in Chile, adolescents usually obey their parents, but if they do something their parents might not like, they keep it secret (Darling et al., 2008). By contrast, many U.S. adolescents deliberately provoke an argument by boldly announcing what they think is permissible, even if it is something they themselves would not do (Cumsille et al., 2010). Filipino adolescents expect autonomy in daily choices but not in life goals: Parental advice is sought and usually followed in the four aspects of identity explained earlier (Russel et al., 2010).

Several researchers have compared parent—

Yet culture also has an impact, as demonstrated in a study of pubescent Hong Kong students who were proficient in both Chinese and English (they spoke Chinese with their parents, but their education was in English) (Wang et al., 2010).

In this study, bilingual researchers asked questions in English to half the children and in Chinese to the other half. All the children replied, in the language the questioner used, about their memories, self-

Especially in early adolescence, descriptions in Chinese were more social while descriptions in English were more individualistic. It was not the words themselves that influenced the children, of course, but rather the ideological framework evoked when a researcher spoke English or Chinese (e.g., Hong Kong’s centuries of British heritage or the millennia of mainland Chinese culture). The researchers interpreted these results to mean that adolescents are strongly influenced by their culture, thinking as well as talking as the culture expects.

Closeness Within the Family

KATHRIN ZIEGLER/GETTY IMAGES

More important than family conflict or individualism may be family closeness, which has four aspects:

- Communication (Do family members talk openly with one another?)

- Support (Do they rely on one another?)

- Connectedness (How emotionally close are they?)

- Control (Do parents encourage or limit adolescent autonomy?)

No social scientist doubts that the first two, communication and support, are helpful, perhaps essential, for healthy development. Patterns set in place during childhood continue, ideally buffering some of the turbulence of adolescence (Cleveland et al., 2005; Laursen & Collins, 2009). Regarding the next two, connectedness and control, consequences vary and observers differ in what they see. How do you react to this example, written by one of my students?

464

I got pregnant when I was sixteen years old, and if it weren’t for the support of my parents, I would probably not have my son. And if they hadn’t taken care of him, I wouldn’t have been able to finish high school or attend college. My parents also helped me overcome the shame that I felt when … my aunts, uncles, and especially my grandparents found out that I was pregnant.

[I., personal communication]

My student is grateful to her parents, but you might wonder whether teenage motherhood gave her parents too much control, requiring her dependence when she should have been seeking her own identity. Indeed, had they somehow allowed her to become pregnant, by permitting her to have time alone with a boy but not educating her about birth control?

An added complexity is that this young woman’s parents had emigrated from South America. Cultural expectations affect everyone’s responses, so her dependence may have been normative for her culture but not elsewhere. A longitudinal study of nonimmigrant adolescent mothers in the U. S. found that most (not all) fared best if their parents were supportive but did not take over child care (Borkowski et al., 2007). Whether this is true in other nations has not been reported.

parental monitoring Parents’ ongoing awareness of what their children are doing, where, and with whom.

A related issue is parental monitoring—that is, parental knowledge about each child’s whereabouts, activities, and companions. Many studies have shown that, when parental knowledge is the result of a warm, supportive relationship, adolescents are likely to become confident, well-

Thus, monitoring may signify a mutual, close interaction (Kerr et al., 2010). However, monitoring may be harmful when it derives from suspicion instead of from a warm connection. Especially in early adolescence, if adolescents resist telling their parents much of anything, they are more likely to develop problems such as aggression against peers, law-

Control is another aspect of parenting that can backfire. Adolescents expect parents to exert some control, especially over moral issues. However, overly restrictive and controlling parenting correlates with many adolescent problems, including depression (Brown & Bakken, 2011). Decreasing control over the years of adolescence is best, according to a longitudinal study of 12-

465

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Parents, Genes, and Risks

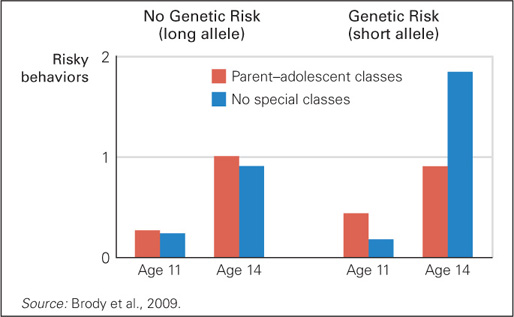

Research on human development has many practical applications. This was evident in a longitudinal study (first mentioned in Chapter 1) of African American families in rural Georgia that involved 611 parents and their 11-

The parents learned the following:

- The importance of being nurturing and involved

- The importance of conveying pride in being African American (called racial socialization)

- How monitoring and control benefit adolescents

- Why clear norms and expectations reduce substance use

- Strategies for communication about sex

The 11-

- The importance of having household rules

- Adaptive behaviors when encountering racism

- The need for making plans for the future

- The differences between them and peers who use alcohol

After that first hour, the parents and 11-

Then, four years after the study began, the researchers read new research that found heightened risks of depression, delinquency, and other problems for people with the short allele of the 5-

That 14 hours or fewer of training (some families skipped sessions) had an impact on genetically sensitive boys is amazing, given all the other influences surrounding these boys over the years. Apparently, since the parent—

Other Adults

Parents are important to an adolescent, but so are many other adults. One of the admirable characteristics of most adolescents is that they know many people, sometimes seeking advice and help from neighbors, teachers, relatives and so on.

Impact is notable when an adult takes time to listen to a child. For many youths, the most patient advisors are family members—

466

In addition, adults with no biological relationship to the young person can be significant (Chang et al., 2010; Scales et al., 2006). For instance, regarding the four arenas of identity development (religion, politics, vocation, gender), clergy can affect a young person’s faith, political leaders can mold values, school counselors can influence vocational aspirations, and adults in satisfying sexual relationships can be role models (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). In addition, many adolescents admire celebrities—

SUMMING UP

Relationships with adults are essential during adolescence. Parents and adolescents often bicker over small things, especially in the first years after puberty, but squabbling does not mean that the relationship is destructive. In fact, parental guidance and ongoing communication promote adolescents’ psychosocial health. Among the signs of a healthy parent-