16.3 Peer Power

Adolescents rely on peers to help them navigate the physical changes of puberty, the intellectual challenges of high school, and the social changes of leaving childhood. Friendships are important at every stage, but during early adolescence popularity is most coveted (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2010).

Observation Quiz There are dramatic differences among teenagers in these two nations as well. What three differences can you see? (See answer, page 468)

Answer to Observation Quiz (from page 466: (1) The U.S. friends are of both sexes; it’s all boys in Sudan. (2) Recreational use of inner tubes in the United States; inner tubes are used only for tires in Sudan. (3) The boys in Sudan are excited to show off their cell phones, which would be unlikely in the United States. There are also many differences in clothing, as you can see.

MARCO DI LAURO/GETTY IMAGES

467

Peers and Parents

Adults are sometimes unaware of adolescents’ desire for respect from their contemporaries. I did not recognize this at the time with my own children:

- Our oldest daughter wore the same pair of jeans in tenth grade, day after day. She washed them each night by hand and asked me to put them in the dryer early each morning. My husband was bewildered. “Is this some weird female ritual?” he asked. Years later, she explained that she was afraid that if she wore different pants each day, her classmates would think she cared about her clothes and then criticize her choices.

- Our second daughter, at 16, pierced her ears for the third time. When I asked if this meant she would do drugs, she laughed at my ignorance. I later noticed that many of her friends had multiple holes in their ear lobes.

- At age 15, our third daughter was diagnosed with cancer. My husband and I weighed opinions from four physicians, each explaining treatment that would minimize the risk of death. She had other priorities: “I don’t care what you choose, as long as I keep my hair.” (Now her health is good, and her hair grew back.)

- Our youngest, in sixth grade, refused to wear her jacket (it was new; she had chosen it), even in midwinter. Not until high school did she tell me she did it so that her middle school classmates would think she was tough.

In retrospect, I am amazed that I was unaware of the power of peers.

Sometimes adults conceptualize adolescence as a time when peers and parents are at odds, or worse, as a time when peer influence overtakes parental influence. This is not true. Relationships with parents are the prototype for peer relationships: Healthy communication and support from parents make constructive peer relationships more likely.

Parents and peers are often mutually reinforcing, although many adolescents downplay the influence of their parents and many parents are unaware of the influence of peers, as I was. Only when parents are harsh or neglectful does peer influence reign alone (Bakken & Brown, 2011).

Peer Pressure

For every adolescent, peer opinions and friends are vital. One high school boy said:

A lot of times I wake up in the morning and I don’t want to go to school, and then I’m like, you know, I have got this class and these friends are in it, and I am going to have fun. That is a big part of my day—

[quoted in Hamm & Faircloth, 2005, p. 72]

peer pressure Encouragement to conform to one’s friends or contemporaries in behavior, dress, and attitude; usually considered a negative force, as when adolescent peers encourage one another to defy adult authority.

Adults sometimes fear peer pressure; that is, they fear that peers will push an adolescent to use drugs, break the law, or do other things their child would never do alone. But peers are more helpful than harmful (Audrey et al., 2006; Nelson & DeBacker, 2008), especially in early adolescence, when biological and social stresses can be overwhelming. In later adolescence, teenagers are less susceptible to peer pressure, either positive or negative (Monahan et al., 2009).

Peers may be particularly helpful for adolescents of minority and immigrant groups as they strive to achieve ethnic identity, attaining their own firm (not confused or foreclosed) understanding of what it means to be Asian, African, Latino, and so on. The larger society provides stereotypes and prejudice, and parents ideally describe ethnic heroes and reasons to be proud (Umana-

468

The social context is especially crucial. For example, in large schools with many ethnic groups, friends from the same background help adolescents avoid feeling adrift and alone, as they resist social prejudice and yet distance themselves from the patterns and attitudes of their parents (Kiang et al., 2009).

Social Networking

You read in Chapter 15 about the dangers of technology. Remember, however, that although some adolescents seem addicted to video games or the Internet, most are not. Technology is a tool, which might exacerbate depression or self-

Despite adult fears to the contrary, technology usually brings friends together in adolescence (Mesch & Talmud, 2010). This is obvious with texting and email, but also occurs with video games. Many games now pit one player against another, or require cooperation among several players (Collins & Freeman, 2013). Technology users, including video game players, are usually at least as extraverted and socially connected as other adolescents.

Although most social networking is between friends who know each other well, the Internet may be a lifeline for teenagers who are isolated because of their sexual orientation, culture, religion, or native language. Furthermore, online resources for teens struggling with depression, addiction, and countless other issues are sometimes particularly helpful, partly because they are frequently anonymous—

Especially for Parents of a Teenager Your 13-

Response for Parents of a Teenager: Remember: Communicate, do not control. Let your child talk about the meaning of the hairstyle. Remind yourself that a hairstyle in itself is harmless. Don’t say “What will people think?” or “Are you on drugs?” or anything that might give your child reason to stop communicating.

469

A particular niche is found within technology for adolescents with special health needs. During these years, many of them refuse to follow special diets, take medication, see doctors monthly, do exercises, or whatever. Technology can literally save lives, as shown with teenagers who have diabetes: They monitor their insulin via cell phone, talk to the doctor via Skype, and talk to other young people with diabetes via Internet chat (Harris et al., 2012).

Selecting Friends

deviancy training Destructive peer support in which one person shows another how to rebel against authority or social norms.

Peers are often beneficial, but they can lead one another into trouble. Collectively, peers sometimes provide deviancy training, whereby one person shows another how to rebel against social norms (Dishion et al., 2001). However, innocent teens are not corrupted by deviant friends. Adolescents choose their friends and models—

A developmental progression can be traced: The combination of “problem behavior, school marginalization, and low academic performance” at age 11 leads to gang involvement two years later, deviancy training two years after that, and violent behavior at age 18 or 19 (Dishion et al., 2010, p. 603). This cascade is not inevitable; adults need to engage marginalized 11-

To further understand the impact of peers, examination of two concepts is helpful: selection and facilitation. Teenagers select friends whose values and interests they share, abandoning former friends who follow other paths. Then friends facilitate destructive or constructive behaviors. It is easier to do wrong (“Let’s all skip school on Friday”) or right (“Let’s study together for the chem exam”) with friends. Peer facilitation helps adolescents act in ways they are unlikely to act on their own.

Thus, adolescents select and facilitate, choose and are chosen. Happy, energetic, and successful teens have close friends who themselves are high achievers, with no major emotional problems. The opposite also holds: Those who are drug users, sexually active, and alienated from school choose compatible friends.

For instance, one U.S. study found that “tough” and “alternative” crowds felt that teenagers should question every adult rule, whereas the “prep” crowd thought that parental authority was usually legitimate (Daddis, 2010). A study in Finland found that students with high grades criticized those who prioritized sports or did not study, who reciprocated by disliking the honors crowd (Laursen et al., 2010).

A study of identical twins from ages 14 to 17 found that selection typically preceded facilitation, rather than the other way around. Those who later rebelled chose lawbreaking friends at age 14 more than did their more conventional twin (Burt et al., 2009). A study of teenage use of cigarettes also found that selection preceded peer pressure (Kiuru et al., 2010). Peers provide opportunity and encouragement for what adolescents already want to do.

Romance

Half a century ago, Dexter Dunphy (1963) described the sequence of male—

- Groups of friends, exclusively one sex or the other

- A loose association of girls and boys, with public interactions within a crowd

- Small mixed-

sex groups of the advanced members of the crowd - Formation of couples, with private intimacies

Culture affects the timing and manifestation of each step on Dunphy’s list, but subsequent research in many nations validates the sequence. Heterosexual youths worldwide (and even the young of other primates) avoid the other sex in childhood and are attracted to them by adulthood. This universal pattern suggests that biology underlies this sequence.

470

The peer group is part of this process. Romantic partners, especially in early adolescence, are selected not for their individual traits as much as for the traits that peers admire. If the leader of a girls’ group of close friends pairs with the leader of a boys’ group, the unattached members of the two cliques tend to pair off as well. A classic example is football players and cheerleaders: They often date each other. Pairing of groups allows easy double or triple dating, makes it easier to have a mixed-

First Love

Teens’ first romances typically occur in high school, with girls having a steady partner more often than boys do. Exclusive commitment is desired, but “cheating,” flirting, switching, and disloyalty are rife. Breakups are common, as are unreciprocated crushes. All of this can be devastating, with emotions such as hatred and despair leading to irrational revenge or impulsive suicide. In such cases, peer support can be a lifesaver; friends help adolescents cope with romantic ups and downs (Mehta & Strough, 2009).

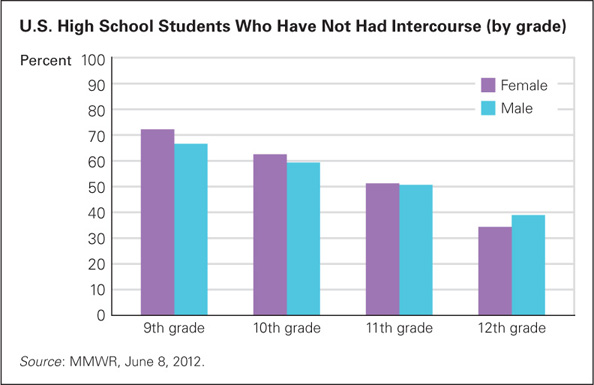

Contrary to adult fears, many teenage romances do not include sexual intercourse. In the United States in 2011, even though about one-

For instance, twice as many ninth-

Same-Sex Romances

sexual orientation A term that refers to whether a person is sexually and romantically attracted to others of the same sex, the opposite sex, or both sexes.

Some adolescents are attracted to peers of the same sex. Sexual orientation refers to the direction of a person’s erotic desires. One meaning of orient is to “turn toward”; thus, sexual orientation refers to whether a person is romantically attracted to (turned on by) people of the other sex, the same sex, or both sexes. Sexual orientation can be strong, weak, overt, secret, or unconscious.

Currently in North America and western Europe, not just two discrete orientations (homosexual and heterosexual) but a range of orientations—

471

Obviously, culture and cohort are powerful. In many nations of Africa and the Middle East, non-

Sexual orientation is surprisingly fluid among adolescents. Girls are particularly likely to decide their orientation only after they have had sexual experiences; many adult lesbian women had other-

Among sexually active teenagers in New York City, 10 percent had had same-

Sex Education

Many adolescents have strong sexual urges but minimal logic about pregnancy and disease, as might be expected from the 10-

As a result, “students seem to waffle their way through sexually relevant encounters driven both by the allure of reward and the fear of negative consequences” (Wagner, 2011, p. 193). They have much to learn. Where do they learn it?

From the Media

Many adolescents learn about sex from the media. The Internet is a common source. Unfortunately websites are often frightening (featuring pictures of diseased sexual organs) or mesmerizing (containing pornography), and the youngest adolescents are particularly naïve.

TV watching peaks at puberty, and the shows most watched by teenagers include sexual content almost seven times per hour (Steinberg & Monahan, 2011). That content is alluring: Almost never does a television character develop an STI, deal with an unwanted pregnancy, or mention (much less use) a condom. Magazines may be even worse. One study found that men’s magazines convince teenage boys that maleness means sexual conquests (Ward et al., 2011).

Adolescents with intense exposure to sexual content on the screen and in music are more often sexually active, but this correlation is controversial (Collins et al., 2011; Steinberg & Monahan, 2011). Do teenagers watch sexy TV because they are sexually active, or does the media cause them to be sexually involved? One analysis concludes that “the most important influences on adolescents’ sexual behavior may be closer to home than Hollywood” (Sternberg & Monahan, 2011, p. 575).

From Parents and Peers

Especially for Sex Educators Suppose adults in your community never talk to their children about sex or puberty. Is that a mistake?

Response for Sex Educators: Yes, but forgive them. Ideally, parents should talk to their children about sex, presenting honest information and listening to the child’s concerns. However, many parents find it very difficult to do so because they feel embarrassed and ignorant. You might schedule separate sessions for adults over 30, for emerging adults, and for adolescents.

As that quote implies, sex education begins at home. Every study finds that explicit parental communication influences adolescents’ behavior (Longmore et al., 2009). However, many parents wait too long to discuss sex. They tend to express clichés and generalities, unaware of their adolescents’ sexuality. Three studies of quite different groups illustrate the problem.

472

- Parents of 12-

year- old girls were asked whether their daughters had hugged or kissed a boy “for a long time” or hung out with older boys (signs that sex information is urgently needed). Only 5 percent of the parents said yes, as did 38 percent of the girls (O’Donnell et al., 2008). - African and Hmong American 14-

to 19- year- olds rarely tell their parents about their romantic encounters. For example, one girl said she was going to the movies with her girlfriend (true) but not that their boyfriends were coming, too (Brown & Bakken, 2011). - Mexican American mothers told their teenagers cuidate, “take care of yourself,” which their teenagers interpreted as advice about health, not contraception. Some of the girls became pregnant, to the mothers distress and surprise. They thought they had warned their daughters and sons to use condoms if they had sex (Moncloa et al., 2010).

What should parents say? That is the wrong question, according to a longitudinal study of thousands of adolescents. Those teens who became sexually active and who were most likely to develop an STI had parents who warned them to stay away from sex. In contrast, adolescents were more likely to remain virgins if they had a warm relationship with their parents—

Especially when parents are silent, forbidding, or vague, adolescent sexual behavior is strongly influenced by peers. Boys are likely to learn about sex from other boys (Henry et al., 2012). Partners also teach each other. However, their lessons are more about pleasure than consequences: Most U.S. adolescent couples do not decide together before they have sex how they will prevent pregnancy and disease, and what they will do if their prevention efforts fail.

From Educators

Sex education varies dramatically by nation. The curriculum for middle schools in most European schools includes information about masturbation, same-

Within the United States, the timing and content of sex education vary by state and community. Some high schools provide comprehensive education, free condoms, and medical treatment; others provide nothing.

Some schools begin sex education in the sixth grade; others wait until senior year. If they begin early, many sex-

One controversy centers on whether abstinence should be taught as the only sexual strategy for adolescents. It is true, of course, that abstaining from sex (including oral sex) prevents STIs and pregnancy, but longitudinal data on several abstinence-

473

SUMMING UP

Contrary to what some adults may think, peer pressure can be positive. Many adolescents rely on friends of both sexes to help them with the concerns and troubles of the teen years. Romances are typical in high school, but early, exclusive, long-

The media and peers are the most common sources for sex information, but not the most accurate. Parents are influential role models, but few provide detailed and current information before adolescents begin experimenting with sex. School instruction may be helpful, but not every curriculum is equally effective, and schools vary in what and when they teach about sex.