16.4 Sadness and Anger

Adolescence is usually a wonderful time, perhaps better for current generations than for any generation before. Nonetheless, troubles plague about 20 percent of youths. Most disorders are comorbid, with several problems occurring at once. Distinguishing between pathology and normal moodiness, between behavior that is seriously troubled versus merely unsettling, is complex.

It is typical for an adolescent to be momentarily less happy and more angry than younger children, but teen emotions often change quickly (Neumann et al., 2011). For a few, however, negative emotions cloud every moment, becoming intense, chronic, even deadly.

Depression

The general emotional trend from late childhood through adolescence is toward less confidence. A dip in self-

On average, however, self-

Parents and peers affect self-

474

familism The belief that family members should support one another, sacrificing individual freedom and success, if necessary, in order to preserve family unity and protect the family from outside sources.

Cultural contexts are influential. One cultural norm is familism—the belief that family members should sacrifice personal freedom and success to care for one another. For Latino youth, self-

However, if a Latino family is characterized by fighting and fragmentation, that reduces self-

Clinical Depression

clinical depression Feelings of hopelessness, lethargy, and worthlessness that last two weeks or more.

Some adolescents sink into clinical depression, a deep sadness and hopelessness that disrupts all normal, regular activities. The causes, including genes and early care, predate adolescence. Then the onset of puberty—

Sex hormones are probably part of the reason, but girls also experience social pressures from their families, peers, and cultures that boys do not (Naninck et al., 2011). Perhaps the combination of biological and psychosocial stresses causes some to slide into depression. Genes are involved as well.

One study found that the short allele of the serotonin transporter promoter gene (5-

rumination Repeatedly thinking and talking about past experiences; can contribute to depression.

A cognitive explanation for gender differences in depression focuses on rumination—talking about, remembering, and mentally replaying past experiences. Girls ruminate much more than boys, and rumination often leads to depression (Michl et al., 2013). For that reason, close mother—

Suicide

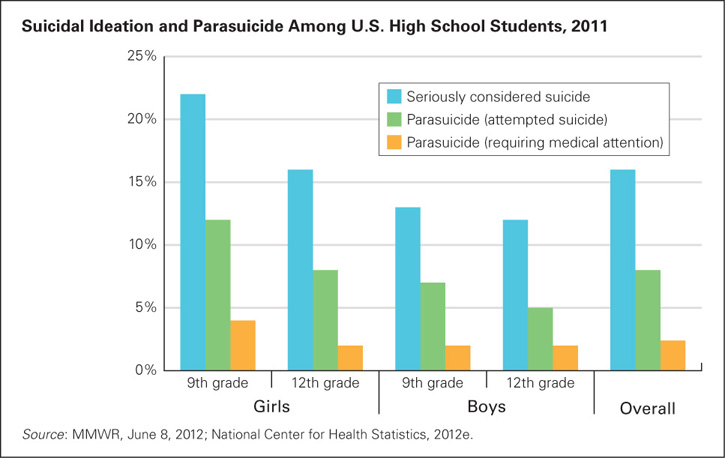

Serious, distressing thoughts about killing oneself (called suicidal ideation) are most common at about age 15. The 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey revealed that more than one-

suicidal ideation Thinking about suicide, usually with some serious emotional and intellectual or cognitive overtones.

475

parasuicide Any potentially lethal action against the self that does not result in death. (Also called attempted suicide or failed suicide.)

Suicidal ideation can lead to parasuicide, also called attempted suicide or failed suicide. Parasuicide includes any deliberate self-

As you see in Figure 16.5, parasuicide can be divided according to those who require medical attention (surgery, pumped stomachs, etc.) and those who do not, but any parasuicide is a warning. If there is a next time, the person may die.

Internationally, rates of teenage parasuicide range between 6 and 20 percent. Among U.S. high school students in 2011, 9 percent of the girls and 6 percent of the boys tried to kill themselves in the previous year (MMWR, June 8, 2012; see Figure 16.5).

While suicidal ideation during adolescence is common, completed suicides are not. The U.S. annual rate of completed suicide for people aged 15 to 19 (in school or not) is about 8 per 100,000, or 0.008 percent, half the rate for adults aged 20 and older.

cluster suicides Several suicides committed by members of a group within a brief period of time.

Because they are not logical and analytical, adolescents are particularly affected when they hear about a suicide, either through the media or from peers (Insel & Gould, 2008). That makes them susceptible to cluster suicides, a term for the occurrence of several suicides within a group over a brief span of time.

In every large nation except China, girls are more likely to attempt suicide but boys are more likely to complete it. In the United States, adolescent boys kill themselves four times more often than girls (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). The reason may be method: Males typically jump from high places or shoot themselves (immediately lethal), whereas females often swallow pills or cut their wrists, which allows time for conversation, intervention, and second thoughts.

Especially for Journalists You just heard that a teenage cheerleader jumped off a tall building and died. How should you report the story?

Response for Journalists: Since teenagers seek admiration from their peers, be careful not to glorify the victim’s life or death. Facts are needed, as is, perhaps, inclusion of warning signs that were missed or cautions about alcohol abuse. Avoid prominent headlines or anything that might encourage another teenager to do the same thing.

476

REUTERS/PHILIPPE WOJAZER/LANDOV

Delinquency and Defiance

Like low self-

Externalizing actions are obvious. Many adolescents slam doors, curse parents, and tell friends exactly how badly other teenagers (or siblings or teachers) have behaved. Some teenagers—

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Teenage Rage: Necessary?

Is it normal for adolescents to challenge and disobey authority? Perhaps teenagers need to break some laws, curse some adults, rebel against their parents in order to establish their own identity and become independent adults. The best-

We all know individual children who, as late as the ages of fourteen, fifteen or sixteen, show no such outer evidence of inner unrest. They remain, as they have been during the latency period, “good” children, wrapped up in their family relationships, considerate sons of their mothers, submissive to their fathers, in accord with the atmosphere, idea and ideal of their childhood background. Convenient as this may be, it signifies a delay of their normal development and is, as such, a sign to be taken seriously.

[A. Freud, 1958/2000, p. 263]

Contrary to Freud, many psychologists, most teachers, and almost all parents are quite happy with well-

Dozens of longitudinal studies confirm that most adolescents learn to express their anger in acceptable ways. Only a minority are explosive: breaking something, hurting someone. Those who are not rebellious develop well, and those who are explosive can still learn to modify their anger.

Which view do you hold? Does your personal experience, remembering your adolescence, indicate that rebellion is normal? Or do you think that respect for adults, especially parents, is a common occurrence during adolescence, leading to a healthy adulthood?

477

Breaking the Law

Both the prevalence (how widespread) and the incidence (how frequent) of criminal actions are more common during adolescence than earlier or later. Arrest statistics in every nation reflect this fact, and confidential self-

In one study of 1,559 urban seventh-

Research on confessions to a crime negates the notion that adolescents are often serious criminals. In the United States, about 20 percent of confessions are false: That is, a person confesses to a crime he or she did not commit. False confessions are more likely in adolescence, partly because of brain immaturity and partly because young people want to help their family members and please adults—

adolescence-

A leading researcher on juvenile delinquency says that we need to distinguish two kinds of teenage lawbreakers. Most juvenile delinquents are adolescence-

life-

The other kind of delinquents are l ife-

The criminal records of both types of teenagers may be similar. However, if adolescence-

Causes of Delinquency

One way to analyze the likelihood of adolescent crime is to consider earlier patterns and stop delinquency before the police become involved. Parents and schools need to develop strong and protective relationships with children, teaching them emotional regulation and prosocial behavior, as explained in earlier chapters. In adolescence, three pathways to dire consequences can be seen:

478

- Stubbornness can lead to defiance, which can lead to running away—

runaways are often victims as well as criminals (e.g., falling in with prostitutes and petty thieves). - Shoplifting can lead to arson and burglary.

- Bullying can lead to assault, rape, and murder.

Each of these pathways demands a different response. The rebelliousness of the first can be channeled or limited until more maturation and less impulsive anger prevail. Those on the second pathway require stronger human relationships and moral education. Those on the third present the most serious problem; Their bullying should have been stopped earlier, as Chapters 10 and 13 explained. In all cases, early warning signs are present, and intervention is more effective earlier than later (Loeber & Burke, 2011).

Adolescent crime in the United States and many other nations has decreased in the past 20 years. Only half as many juveniles under age 18 are currently arrested for murder than was true in 1990. For almost every crime, boys are arrested at least twice as often as girls are.

No explanations for this declining rate or for gender differences are accepted by all scholars. Regarding gender, it is true that boys are more overtly aggressive and rebellious at every age, but this may be nurture, not nature (Loeber et al., 2013). Some studies find that female aggression is typically limited to family and friends, and therefore less likely to lead to an arrest.

Regarding the drop in adolescent crime, many possibilities have been suggested: fewer high school dropouts (more education means less crime); wiser judges (who now have community service as an option); better policing (arrests for misdemeanors are up, which may warn parents); smaller families (parents are more attentive to each of two children than each of twelve); better contraception and legal abortion (wanted children are less likely to become criminals); stricter drug laws (binge drinking and crack use increase crime); more immigrants (who are more law abiding); less lead (early lead poisoning reduces brain functioning); and more.

Nonetheless, adolescents are more likely to break the law than adults are. To be specific, the arrest rate for 15-

SUMMING UP

Compared with people of other ages, many adolescents experience sudden and extreme emotions that lead to powerful sadness and explosive anger. Supportive families, friends, neighborhoods, and cultures usually contain and channel such feelings. For some teenagers, however, emotions are unchecked or intensified by their social contexts. This situation can lead to parasuicide (especially for girls), to minor lawbreaking (for both sexes), and, less often, to completed suicide or jail (especially for boys). Pathways to crime can be seen in childhood and early adolescence: Intervention is most effective then as well.