18.1 Postformal Thought

Thinking in adulthood differs from earlier thinking in three major ways: It is more practical, more flexible, and more dialectical (that is, it is able to consider and integrate opposing or conflicting ideas). Taken together, these characteristics may constitute a fifth stage of cognitive development, combining a new “ordering of formal operations” with a “necessary subjectivity” (Sinnott, 1998, p. 24).

518

If postformal thought occurs, its appearance is gradual, not tied to any particular year or decade. Emerging adulthood is the usual, but not the only, time that people develop the ability to think as adults.

The Practical and the Personal: A Fifth Stage?

postformal thought A proposed adult stage of cognitive development, following Piaget’s four stages, that goes beyond adolescent thinking by being more practical, more flexible, and more dialectical (that is, more capable of combining contradictory elements into a comprehensive whole).

The term postformal thought originated because several developmentalists agreed that Piaget’s fourth stage, formal operational thought, was inadequate to describe adult thinking. They proposed a fifth stage. As one group of scholars explained, in postformal thought “one can conceive of multiple logics, choices, or perceptions…in order to better understand the complexities and inherent biases in ‘truth’” (Griffin et al., 2009, p. 173).

Postformal thinkers do not wait for someone else to present a problem to solve. They take a flexible and comprehensive approach, considering various aspects of a situation beforehand, anticipating problems, dealing with difficulties in a timely manner rather than denying, avoiding, or procrastinating. As a result, postformal thought is more practical as well as more creative and imaginative than earlier thinking is (Kallio, 2011; Su, 2011).

As you remember, adolescents use two modes of thought, but combining them is difficult. High school students may use formal analysis to distill universal truths, develop arguments, and resolve the world’s problems, or they may think spontaneously and emotionally, but they rarely combine the two. They can analyze, but they may not anticipate the consequences of their actions. [Lifespan Link: The dual processing that characterizes adolescent thought is discussed in Chapter 15.]

Time Management

One way to contrast postformal and formal thinking is to understand how adolescents and adults think about time. In adulthood, intellectual skills are harnessed to real educational, occupational, and interpersonal concerns. Conclusions and consequences matter; setting priorities includes postponing some tasks in order to accomplish others.

Interestingly, good time management is characteristic of successful, conscientious, part-

Another example of priorities is evident in the first week of college classes: most professors (in contrast to high school teachers) announce assignments and due dates for the entire semester and expect students “to decide for themselves when to do [the work],…invoking that dreaded phrase time management” (Howard, 2005, p. 15). Emerging adults struggle with procrastination: time management is a challenge that adults gradually master as their cognition matures (Berg, 2008).

Generally, in the process of developing postformal thought, adults accept and adapt to the many contradictions and inconsistencies of everyday experience, becoming less playful and more practical. They consider most of life’s answers to be provisional, not necessarily permanent; they take irrational and emotional factors into account.

519

To give an example from time management, planning when to work on a term paper that is due in a month may include personal emotions and traits (e.g., anxiety, perfectionism), other obligations (at home and at work), and practical considerations (rewriting, library reserves, computer and printer availability, formatting). Adolescents might ignore all this until the last moment; emerging adults hopefully know better.

delay discounting The tendency to undervalue, or downright ignore, future consequences and rewards in favor of more immediate gratification.

No one always plans well for the future, however. A common logical error is delay discounting—the tendency to undervalue (discount) future events. If offered $100 now or $110 later, people usually discount the delayed reward and choose the immediate one. Delay discounting occurs at every age. For example, lottery winners usually choose to take half of their winnings immediately, forfeiting the other half, rather than taking all in installments. Delay discounting, in effect, is an example of the difficulty of postponing immediate gratification.

Gradually, as the prefrontal cortex matures, people become better able to plan ahead. Delay discounting is reduced with age (Löckenhoff et al., 2011), but adolescents are particularly likely to underestimate delayed consequences.

This tendency explains a paradox described in the previous chapter. As a result of school classes and media messages, almost all 18-

Objectively, the oldest adults might be more likely to choose immediate gratification since they have fewer future years for any postponed pleasure. But the opposite is true, because postformal thinking allows better planning (Löckenhoff et al., 2011). Postformal thought is more practical, creative, and imaginative than thought in previous stages (Wu & Chiou, 2008). Investment bankers, corporation heads, surgeons, and police detectives all need to combine many modes of thought, which is one reason even the smartest young person is not chosen for those roles (Kahneman, 2011).

Really a Stage?

As you have read, some developmentalists doubt Piaget’s stage theory of childhood cognition. Many more question this fifth stage. As two scholars writing about emerging adulthood wrote, “Who needs stages anyway?” (Kloep & Hendry, 2011).

Piaget himself never labeled or described postformal cognition. Certainly, if cognitive stage means attaining a new set of intellectual abilities (such as the symbolic use of language that distinguishes sensorimotor from preoperational thought), then adulthood has no stages.

However, as described in Chapter 15, the prefrontal cortex is not fully mature until the early 20s, and new dendrites connect throughout life. As more is understood about brain development after adolescence, it seems that the characteristics of postformal thought (practical, flexible, dialectical) are more evident as the brain matures (Lemieux, 2012).

Moreover, the prefrontal cortex seems particularly connected to social understanding (Barbey et al., 2009): Several studies find that adults tend to think in ways that adolescents do not, partly because they benefit from a wider understanding and greater experience of the social world.

520

For instance, one study of people aged 13 to 45 found that logical skills improved from adolescence to emerging adulthood and then remained steady, as might be expected as formal operational thinking becomes well established. However, social understanding continued to advance (Demetriou & Bakracevic, 2009). (Social understanding includes knowing how best to interact with other people—

Of course, context and culture are crucial: A 30-

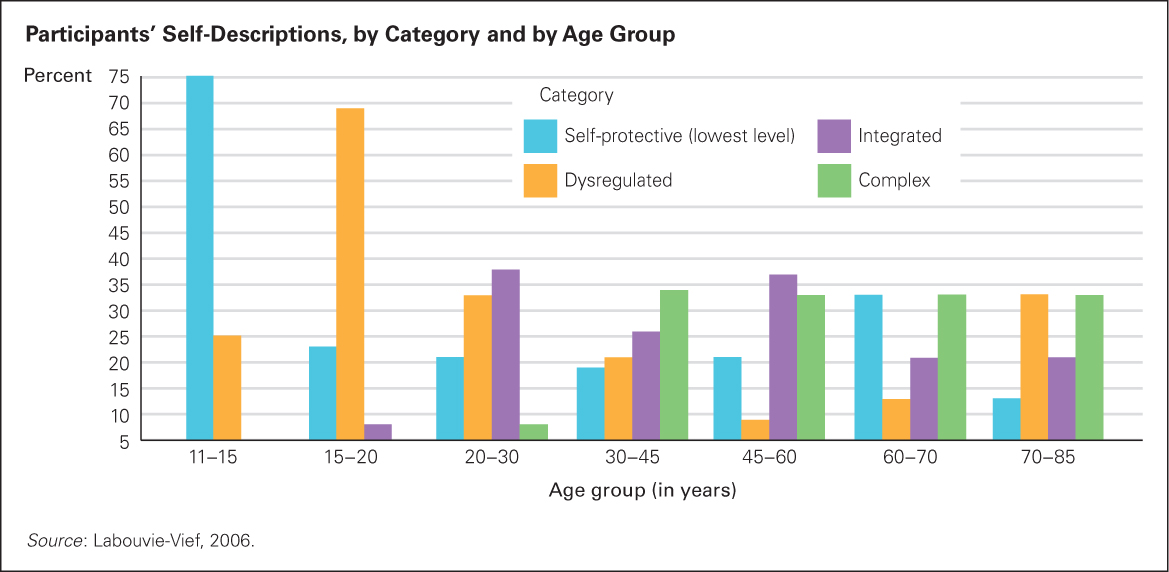

In one U.S. study, researchers asked adolescents and adults to describe themselves (Labouvie-

As life experiences accumulated, adults expressed themselves differently. No one under age 20 was at the advanced “integrated” stage (see Figure 18.1). The largest shift occurred between adolescence and emerging adulthood. As the lead researcher wrote, adult thinking “can be ordered in terms of increasing levels of complexity and integration” (Labouvie-

Thus, many scholars find that thinking changes both qualitatively and quantitatively during adulthood (Bosworth & Hertzog, 2009, Lemieux, 2012; Kallio, 2011). The term fifth stage may be a misnomer, and postformal may imply a depth of intellectual thought that few people attain, but adults can and often do reach a new cognitive level when their brains and life circumstances allow it.

521

Combining Subjective and Objective Thought

subjective thought Thinking that is strongly influenced by personal qualities of the individual thinker, such as past experiences, cultural assumptions, and goals for the future.

objective thought Thinking that is not influenced by the thinker’s personal qualities but instead involves facts and numbers that are universally considered true and valid.

One of the practical skills of postformal thinking is the ability to combine subjective and objective thought. Subjective thought arises from personal experiences and perceptions; objective thought follows abstract, impersonal logic. Traditional models of formal operational thinking value impersonal logic (such as, on Piaget’s balance scale, the mathematical relationship between weight and distance) and devalue subjective feelings, personal faith, and emotional experience.

Purely objective, logical thinking may be maladaptive when one is navigating the complexities and commitments of daily life, especially for the social understanding needed for productive families, workplaces, and neighborhoods. Subjective feelings and individual experiences must be taken into account because objective reasoning alone is too limited, rigid, and impractical.

Yet subjective thinking is also limited. Truly mature thought involves an interaction between abstract, objective forms of processing and expressive, subjective forms, the dual processing described in Chapter 15. Adult thought does not abandon objectivity; instead, “postformal logic combines subjectivity and objectivity” (Sinnott, 1998, p. 55) to become personal and practical.

Solving the complex problem of combining emotion and logic is the crucial practical challenge for adults: “Emerging adulthood truly does emerge as a somewhat crucial period of the life span…[because] complex, critical, and relativizing thinking emerges only in the 20s” (Labouvie-

522

Without this consolidation of intellect and emotion, behavioral extremes (such as those that lead to binge eating, anorexia, obesity, addiction, and violence) and cognitive extremes (such as believing that one is the best or the worst person on earth) are common. Those are typical of the egocentrism of adolescence—

As an example of such balance, an emerging adult student of mine wrote:

Unfortunately, alcoholism runs in my family…. I have seen it tear apart not only my uncle but my family also…. I have gotten sick from drinking, and it was the most horrifying night of my life. I know that I didn’t have alcohol poisoning or anything, but I drank too quickly and was getting sick. All of these images flooded my head about how I didn’t want to ever end up the way my uncle was. From that point on, whenever I have touched alcohol, it has been with extreme caution…. When I am old and gray, the last thing I want to be thinking about is where my next beer will come from or how I’ll need a liver transplant.

[Laura, personal communication]

Especially for Someone Who Has to Make an Important Decision Which is better: to go with your gut feelings or to consider pros and cons as objectively as you can?

Response for Someone Who Has to Make an Important Decision: Both are necessary. Mature thinking requires a combination of emotions and logic. To make sure you use both, take your time (don’t just act on your first impulse) and talk with people you trust. Ultimately, you will have to live with your decision, so do not ignore either intuitive or logical thought.

Laura’s thinking about alcohol is postformal in that it combines knowledge (e.g., of alcohol poisoning) with emotions (images flooding her head). Note that she is cautious, not abstinent; she can combine the objective awareness of her genetic potential with the subjective experience of wanting to be part of the crowd. She can combine both modes of thought to reach a conclusion that works for her, without needing searing personal experiences (becoming an active alcoholic and reaching despair) and then going to the other logical extreme (avoiding even one sip, as recovering alcoholics must).

This development of postformal thought regarding alcohol is seen in most U.S. adults over time. As explained in the previous chapter, those in their early 20s are more likely than people of any other age to abuse alcohol and other drugs. With personal experience and learning from others (social norms), however, cognitive maturity leads most adults to drink occasionally and moderately from then on (Schulenberg et al., 2005). Looking at all the research makes it apparent that adolescents tend to use either objective or subjective reasoning, but adults combine the two.

Cognitive Flexibility

The ability to be practical—

For example: Corporate restructuring might require finding another job; a failure of birth control might mean an unwanted pregnancy; a parent’s illness might require changing plans for higher education; an economic collapse might make a mortgage impossible to sustain.

Almost every adult experiences unanticipated events such as these. Cognitive flexibility allows the adult to avoid retreating into either emotions or intellect. Research on practical problem-

Thus, a hallmark of postformal cognition is intellectual flexibility, a characteristic that is far more typical of emerging adults than of younger people. The “fundamental flux of emerging adulthood” (Tanner et al., 2009, p. 34) comes from the realization that each perspective is only one of many, that each problem has several solutions, and that knowledge is dynamic, not static. Emerging adults begin to realize that “there are multiple views of the same phenomenon” (Baltes et al., 1998, p. 1093). Listening to others, considering diverse opinions, is a sign of flexibility.

523

Working Together

Consider this problem:

Every card in a pack has a letter on one side and a number on the other. Imagine that you are presented with the following four cards, each of which has something on the back. Turn over only those cards that will confirm or disconfirm this proposition: If a card has a vowel on one side, then it always has an even number on the other side.

E 7 K 4

Which cards must be turned over?

The difficulty of this puzzle is “notorious in the literature of human reasoning” (Moshman, 2011, p. 50). Fewer than 10 percent of college students solve it when working independently. Almost everyone wants to turn over the E and the 4—

However, when groups of college students who had guessed wrong on their own then had a chance to discuss the problem together, 75 percent got it right: They avoided the 4 card (even if it has a consonant on the other side, the statement could still be true) and selected the E and the 7 cards (if the 7 has a vowel on the other side, the proposition is proved false).

As in this example, adults can think things through, and change their minds after listening (Moshman, 2011). Think about a time when you thought one thing, which is opposite to what you now think. Probably a combination of logic and social experience caused you to develop your new view. This is cognitive flexibility.

Alternate Solutions

Such data on behavioral change could be attributed to many factors other than cognitive flexibility. However, research that specifically examines adult cognition finds that adults are more likely than children to imagine several solutions for every problem and then to take care in selecting the best one.

For example, young, middle-

Countering Stereotypes

Cognitive flexibility, particularly the ability to change childhood assumptions, is needed to counter stereotypes. Daily life for young adults shows many signs of such flexibility. The very fact that emerging adults marry and become parents years later than their parents did means that, couple by couple, thinking processes lead to conclusions other than those their parents arrived at and to assumptions different from past social assumptions. Of course, early experiences are influential, but for postformal thinkers they are not determinative.

524

Observation Quiz Which of these three college students taking an exam is least vulnerable to stereotype threat?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Anyone could experience stereotype threat, depending on what is being tested and on the students’ history. White males are generally least vulnerable, but if the test is about literature and if the male student has been told that men are deficient at interpreting poetry and fiction, his performance on the exam might be affected by that stereotype.

Research on racial prejudice in adulthood merits closer study. Many American children and adults harbor some implicit bias against African Americans, detectable in their slower reaction time when mentally processing photos of African Americans as compared with photos of European Americans (Baron & Banaji, 2006). This implicit bias may be in the unconscious minds of African Americans themselves, harming their health and well-

By contrast, most people say and believe that they are not racially prejudiced, and their behavior reveals no overt bias. Thus, many adults have both unconscious prejudice and rational nonprejudice—

stereotype threat The thought in a person’s mind that one’s appearance or behavior will be misread to confirm another person’s oversimplified, prejudiced attitudes.

An intriguing discovery regarding unconscious emotions is called stereotype threat, the worry that other people assume that you yourself are stupid, lazy, oversexed, or worse because of your race, sex, age, or appearance. Note that the worry is the threat, quite apart from the behaviors that are based on prejudice.

The mere possibility of being negatively stereotyped arouses emotions that can disrupt cognition as well as emotional regulation. This has been shown with hundreds of studies on dozens of stereotyped groups, of every ethnicity, sex and sexual orientation, and age (Inzlicht & Schmader 2012).

Stereotype threat is likely when circumstances remind a person of a possible threat “in the air,” not an overt threat (Steele, 1997). To stick with the original example, African American men have lower grades in high school and earn only half as many college degrees as their genetic peers, African American women. This disparity has many possible causes; stereotype threat is one of them.

If African American males are aware of the stereotype that they are poor scholars, they might become anxious. That anxiety would reduce their ability to focus on academics. Then, if they underachieve, they might denigrate academic success in order to protect their pride. That would lead to disengagement from studying and ultimately to even lower achievement. The more threatening the learning and testing context is, the worse they will do (Taylor & Walton, 2011).

Indeed, that downward pattern seems to occur exactly, not only for African American men. Hundreds of studies show that almost all humans are harmed by stereotype threat: Women underperform in math, older people are more forgetful, bilingual students stumble with English, and every member of a stigmatized minority in every nation performs less well. Even those sometimes thought to be on top—

The worst part of stereotype threat is that it is self-

525

How do unconscious prejudices relate to postformal thought? Since everyone has some childhood stereotypes hidden in the brain, adults need flexible cognition to overcome them, abandoning the prejudices they learned earlier. Many programs attempt to increase the achievement of individuals whose potential seems unrealized.

Surprisingly successful are colleges that are predominantly for women or African Americans. Such colleges not only have higher graduation rates but also their students tend to be more successful as adults than similar students in colleges where they may be self-

Can stereotype threat be reduced when students are a minority? One multiracial team of scientists had a hypothesis: that stereotype threat will decrease and achievement will increase if people internalize (believe wholeheartedly, not just intellectually) that intelligence is plastic, not inborn. These scientists used a series of measures that convinced African American college students at Stanford University that their ability depended on their personal efforts. That reduced stereotype threat and led to higher grades (Aronson et al., 2002).

This study was the first of many. Books written for the general population, not for academics, often tell the same story of people who notice their own self-

Stereotype threat can create a vicious spiral: Some college admissions personnel wonder if it interferes with college acceptance (Soares, 2012). If minority college applicants fear stereotyping, anxiety may make them too quiet or too talkative in the interview. That may lead to a prejudicial reaction from the admissions officer. If applicants are rejected, they can correctly blame a stereotype, not realizing that they themselves set it in motion.

Postformal thinking allows people to overcome fear and anxiety, no longer denying such unconscious emotions. Is this wishful thinking, or can you recall prejudices you held about others, or about yourself, that no longer impair your thoughts?

Dialectical Thought

dialectical thought The most advanced cognitive process, characterized by the ability to consider a thesis and its antithesis simultaneously and thus to arrive at a synthesis. Dialectical thought makes possible an ongoing awareness of pros and cons, advantages and disadvantages, possibilities and limitations.

Postformal thought, at its best, becomes dialectical thought, which may be the most advanced cognitive process (Basseches, 1984, 1989; Riegel, 1975). The word dialectic refers to the philosophical concept, developed by Hegel two centuries ago, that every idea or truth bears within itself the opposite idea or truth.

thesis A proposition or statement of belief; the first stage of the process of dialectical thinking.

antithesis A proposition or statement of belief that opposes the thesis; the second stage of the process of dialectical thinking.

synthesis A new idea that integrates the thesis and its antithesis, thus representing a new and more comprehensive level of truth; the third stage of the process of dialectical thinking.

To use the words of philosophers, each idea, or thesis, implies an opposing idea, or antithesis. Dialectical thought involves considering both these poles of an idea simultaneously and then forging them into a synthesis—that is, a new idea that integrates the original and its opposite. Note that the synthesis is not a compromise; it is a new concept that incorporates both original ones in some transformative way (Lemieux, 2012).

For example, many young children idolize their parents (thesis), many adolescents are highly critical of their parents (antithesis), and many emerging adults appreciate their parents and forgive their shortcomings, which they attribute to their parents’ background, historical conditions, and age (synthesis).

Because ideas can engender their opposites, the possibility of change is continuous. Each new synthesis deepens and refines the thesis and antithesis that initiated it, with “cognitive development as the dance of adaptive transformation” (Sinnott, 2009, p. 103). Thus, dialectical thinking involves the constant integration of beliefs and experiences with all the contradictions and inconsistencies of daily life. Change throughout the life span is multidirectional, ongoing, and often surprising—

526

Appreciation that life is a series of thesis/antithesis/synthesis is found in the work of every great developmentalist. For instance:

- Educators who agree with Vygotsky that learning is a social interaction within the zone of proximal development (with learners and mentors continually adjusting to each other) take a dialectical approach to education (Vianna & Stetsenko, 2006).

- Piaget could be considered a dialectical thinker, too, in that he thought conflict between new and old ideas was the fuel that fired a new stage of development (Lemieux, 2012).

- Dialectical processes are readily observable by life-

span researchers, who believe that “the occurrence and effective mastery of crises and conflicts represent not only risks, but also opportunities for new development” (Baltes et al., 1998, p. 1041). - Arnett, who coined the term emerging adulthood, wrote that brain organization allows the young adult to move past dualism to multiplicity (Tanner & Arnett, 2011), which can be seen as moving past thesis and antithesis, arriving at a synthesis that recognizes the many aspects of truth.

A “Broken” Marriage

Let’s look at an example of dialectical thought familiar to many: the end of a love affair. A nondialectical thinker might believe that each person has stable, enduring, independent traits. Faced with a troubled romance, then, a nondialectical thinker concludes that one partner (or the other) is at fault, or perhaps the relationship was a mistake from the beginning because the two were a bad match.

By contrast, dialectical thinkers see people and relationships as constantly evolving; partners are changed by time as well as by their interaction. Therefore, a romance becomes troubled not because the partners are fundamentally incompatible, or because one or the other is bad, but because they have changed without adapting to each other. Marriages do not “break” or “fail”; they either continue to develop over time (dialectically) or they stagnate as the two people move apart.

Does this happen in practice as well as in theory? Possibly. Certainly marriages are more likely to end if the couple married as teenagers rather than as adults, perhaps because few adolescents think dialectically. People of all ages are upset when a romance fades, but neurological immaturity makes a young person overcome by jealousy or despair unable to find the synthesis (Fisher, 2006). Older couples think more dialectically and therefore move from thesis (“I love you because you are perfect”) to antithesis (“I hate you—

New demands, roles, responsibilities, and even conflicts become learning opportunities for the dialectical thinker. Students might take a class in an unfamiliar subject, employees might apply for an unexpected promotion, young adults might leave their parents’ household and move to another town or nation. In such situations, when comfort collides with the desire for growth, dialectical thinkers find a new synthesis, gaining insight. This basic idea underlies all continuing education—

527

Culture and Dialectics

Several researchers have compared cognition in Asian and American adults, focusing on dialectical thought. It may be that ancient Greek philosophy led Europeans and North Americans to use analytic, absolutist logic—

For whatever reason, Asians tend to think holistically, about the whole rather than the parts, seeking the synthesis because “in place of logic, the Chinese developed a dialectic” (Nisbett et al., 2001, p. 305). One example is in judging emotions: Westerners are more likely to pay close attention to facial expressions, and Asians are more likely to consider the context, such as surrounding circumstances (Matsumoto et al., 2012).

This leaves Asians open to more possibilities and makes them less likely to conclude that one answer is the only correct one. For example, a study of Canadians, some of them immigrants from China and others native born, found that the Asian Canadians were more tolerant of ambivalence. As a result, when presented with a one-

A series of studies compared three groups of students: Koreans in Seoul, South Korea; Korean Americans who had lived most of their lives in the United States; and U.S.-born European Americans. Individuals in all three groups were told the following:

Suppose you are the police officer in charge of a case involving a graduate student who murdered a professor…. As a police officer, you must establish motive.

[Choi et al., 2003]

Participants were given a list of 97 items of information and were asked to identify the ones they would want to know as they looked for the killer’s motive. Some of the 97 items were clearly relevant (e.g., whether the professor had publicly ridiculed the graduate student), and virtually everyone in all three groups chose them. Some were clearly irrelevant (e.g., the student’s favorite color), and almost everyone left them out.

Other items were questionable (e.g., what the professor was doing that fateful night; how the professor was dressed). Compared with both groups of Americans, the students in Korea asked for 15 more items, on average. The researchers suggest that their culture had taught them to include the entire context in order to find a holistic synthesis (Choi et al., 2003).

Researchers agree that notable differences between Eastern and Western thought are the result of nurture, not nature—

Do not conclude that one way of thinking (either Eastern or Western) is always better. Indeed, the notion that there is one “best way” is not dialectical; most developmentalists think that reflecting flexibly is more advanced than simply sticking to one thesis.

SUMMING UP

A fifth stage of cognition, called postformal thought, may follow Piaget’s fourth stage, formal operational thought. Adults may be better able to combine emotion and logic, both halves of the dual processing of adolescents. Postformal thinking is practical, flexible, and dialectical.

528

Cognition advances in adulthood partly because adults have responsibilities that require both logical analysis and emotional reactions, so problem solving is likely to encourage adults to think of many solutions before they select the best one for the particular circumstances. Cognitive advances and flexibility may allow adults to overcome their stereotypes, move beyond stereotype threat, and adapt their long-