The Life-Span Perspective

life-span perspective An approach to the study of human development that takes into account all phases of life, not just childhood or adulthood.

The life-span perspective (Fingerman et al., 2011; Lerner et al., 2010) takes into account all phases of life and has led to a new understanding of human development as multidirectional, multicontextual, multicultural, multidisciplinary, and plastic (Baltes et al., 2006; Haase et al., 2013; Staudinger & Lindenberger, 2003).

6

Age periods (see Table 1.1) are only a rough guide, a truism particularly apparent in adulthood. For example, emerging adulthood, defined as ages 18 to 25, is not a period accepted by all scholars. Many prefer dividing adulthood into early adulthood for ages 20 to 40, middle adulthood for ages 40 to 65, and late adulthood, said to begin at age 60, 65, or even 70. As emphasized time and again, birthdays are an imperfect measure of aging.

| Infancy | 0 to 2 years |

| Early childhood | 2 to 6 years |

| Middle childhood | 6 to 11 years |

| Adolescence | 11 to 18 years |

| Emerging adulthood | 18 to 25 years |

| Adulthood | 25 to 65 years |

| Late adulthood | 65 years and older |

As you will learn, developmentalists are reluctant to specify chronological ages for any period of development, since time is only one of many variables that affect each person. However, age is a crucial variable, and development can be segmented into periods of study. Approximate ages for each period are given here.

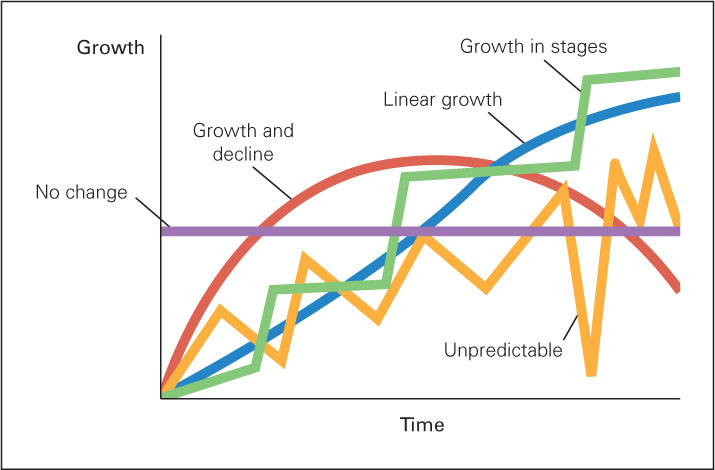

Development Is Multidirectional

Multiple changes, in every direction, characterize the life span. Traits appear and disappear, with increases, decreases, and zigzags (see Figure 1.2). An earlier idea—that all development advances until about age 18, steadies, and then declines—has been refuted by life-span research.

Sometimes discontinuity is evident: Change can occur rapidly and dramatically, as when caterpillars become butterflies. Sometimes continuity is found: Growth can be gradual, as when redwoods add rings over hundreds of years. Some characteristics do not seem to change at all: Almost every zygote is XY or XX, male or female, and chromosomal sex is lifelong.

Humans experience simple growth, radical transformation, improvement, and decline as well as stability, stages, and continuity—day to day, year to year, and generation to generation. Not only do the pace and direction of change vary, but each characteristic follows its own trajectory: Losses in some abilities occur simultaneously with gains in others. For example, babies lose some ability to distinguish sounds from other languages when they begin talking in whatever language they hear, and when adults quit their paid job they often become more creative.

critical period A time when a particular type of developmental growth (in body or behavior) must happen if it is ever going to happen.

The timing of losses and gains, impairments or improvements varies as well. Some changes are sudden and profound because of a critical period, which is either when something must occur to ensure normal development or the only time when an abnormality might occur. For instance, the human embryo grows arms and legs, hands and feet, fingers and toes, each over a critical period between 28 and 54 days after conception. After that, it is too late: Unlike some insects, humans never grow replacement limbs.

We know this fact because of a tragic episode. Between 1957 and 1961, thousands of newly pregnant women in 30 nations took t halidomide, an antinausea drug. This change in nurture (via the mother’s bloodstream) disrupted nature (the embryo’s genetic program). If an expectant woman ingested thalidomide during the 26 days of the critical period for limb formation, her newborn’s arms or legs were malformed or absent (Moore & Persaud, 2007). Whether all four limbs, or just arms, or only hands were missing depended on exactly when the drug was taken. If thalidomide was ingested only before day 28 or after day 54, no harm occurred since the critical period had ended.

7

sensitive period A time when a certain type of development is most likely to happen or happens most easily, although it may still happen later with more difficulty. For example, early childhood is considered a sensitive period for language learning.

Life has few such dramatic critical periods. Often, however, a particular development occurs more easily—but not exclusively—at a certain time. That is called a sensitive period.

An example is learning language. If children do not communicate in their first language between ages 1 and 3, they might do so later (hence, these years are not critical), but their grammar is impaired (hence, these years are sensitive).

Similarly, childhood is a sensitive period for learning to pronounce a second or third language with a native accent. Many adults master a new language, but strangers still ask, “Where are you from?” Native speakers can detect an accent that reveals that the first language was something else.

Often in development, individual exceptions to general patterns occur. Sweeping generalizations, like those in the language example, do not hold true in every case. Accent-free speech usually must be learned before puberty, but exceptional nature and nurture (a person naturally adept at hearing and then immersed in a new language) can result in flawless second-language pronunciation (Birdsong, 2006; Muñoz & Singleton, 2011).

Development Is Multicontextual

The second insight we garner from the life-span perspective is that development is multicontextual. Those many contexts are physical (climate, noise, population density, etc.), family (marital status, family size, members’ age and sex), community (urban, suburban, or rural, multiethnic or not, etc.), and so on, with each context affecting everyone.

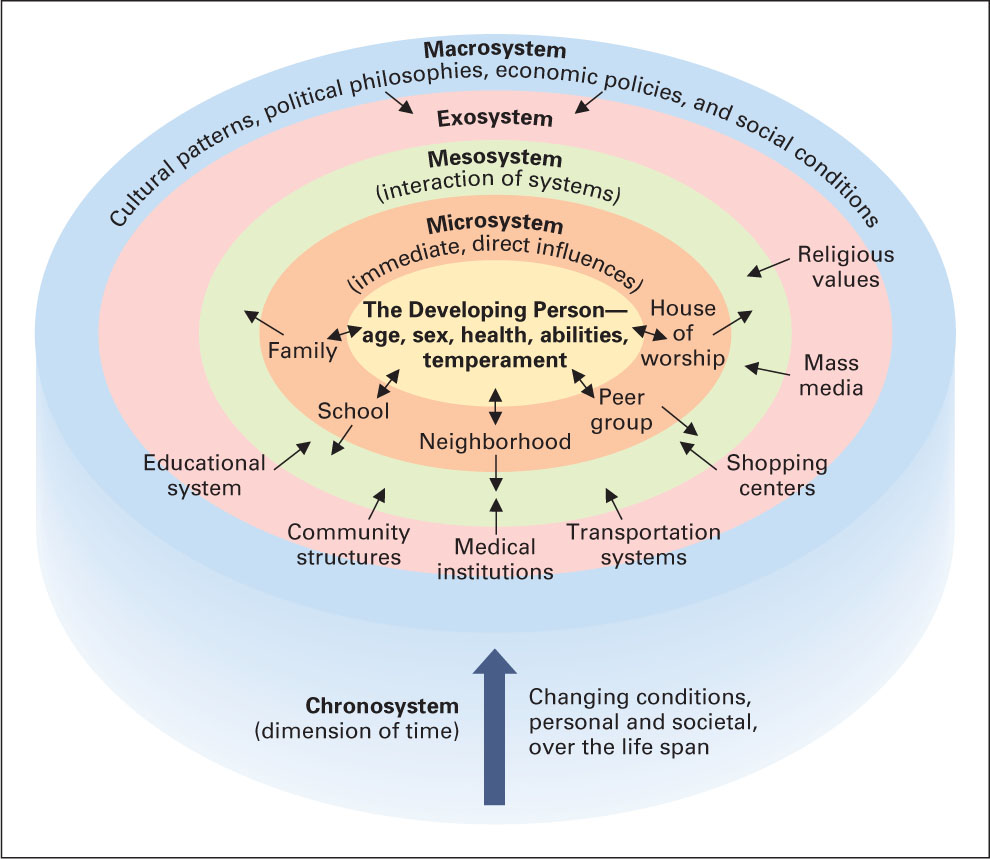

Ecological Systems

ecological-systems approach The view that in the study of human development, the person should be considered in all the contexts and interactions that constitute a life. (Later renamed bioecological theory.)

A leading developmentalist, Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–2005), led the way to considering contexts. Just as a naturalist studying an organism examines the ecology (the relationship between the organism and its environment) of a tiger, or tree, or trout, Bronfenbrenner recommended that developmentalists take an ecological-systems approach (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) to understanding humans.

The ecological-systems approach recognizes three nested levels that surround individuals and affect them (see Figure 1.3). Most obvious are microsystems—each person’s immediate surroundings, such as family and peer group. Also important are exosystems (local institutions such as school and church) and macrosystems (the larger social setting, including cultural values, economic policies, and political processes).

Observation Quiz: What factors suggest this is not a U.S. classroom?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Few U.S. third-grade classes have desks set up in rows, and most U.S. teachers expect children to talk as much as listen—especially when learning a new language. In addition, class size is larger in China (an average of 37 students), which seems likely here, given the layout shown.

Two more systems are related to these three. One is the chronosystem (literally, “time system”), which is the historical context. The other is the mesosystem, consisting of the connections among the other systems.

8

Bronfenbrenner believed that people need to be studied in their natural contexts. He looked at children playing, or mothers putting babies to sleep, or nurses in hospitals—never asking people to come to a scientist’s laboratory for a contrived experiment. Toward the end of his life, Bronfrenbrenner renamed his approach bioecological theory to highlight the role of biology, recognizing that systems within the body (e.g., the sexual-reproductive system, the cardiovascular system) affect the external systems (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006).

Bronfenbrenner’s systems perspective remains useful, as is evident in a recent discussion of climate change (Boon et al., 2012). Two contexts—the historical and the socioeconomic—are so basic to understanding people throughout the life span that we explain them now.

The Historical Context

cohort A group defined by the shared age of its members, who, because they were born at about the same time, move through life together, experiencing the same historical events and cultural shifts.

All persons born within a few years of one another are called a cohort, a group defined by its members’ shared age. Cohorts travel through life together, affected by the interaction of their chronological age with the values, events, technologies, and culture of the era. From the moment of birth, when parents decide the name of their baby, historical context affects what may seem like a private and personal choice (see Table 1.2).

|

Girls: 2012: Sophia, Emma, Isabella, Olivia, Ava |

| 1992: Ashley, Jessica, Amanda, Brittany, Sarah |

| 1972: Jennifer, Michelle, Lisa, Kimberly, Amy |

| 1952: Linda, Mary, Patricia, Deborah, Susan |

| 1932: Mary, Betty, Barbara, Dorothy, Joan |

|

Boys: 2012: Jacob, Mason, Ethan, Noah, William |

| 1992: Michael, Christopher, Matthew, Joshua, Andrew |

| 1972: Michael, Christopher, James, David, John |

| 1952: James, Robert, John, Michael, David |

| 1932: Robert, James, John, William, Richard |

| Source: U.S. Social Security Administration |

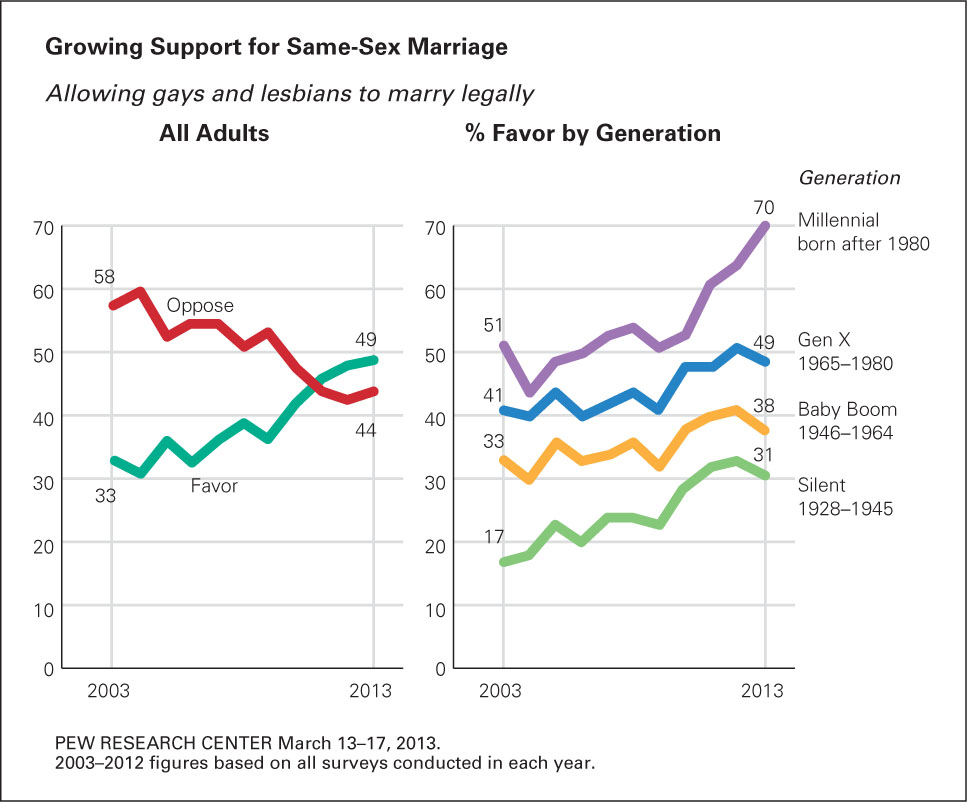

In another life-span example, the years 18 to 25 constitute a sensitive period for consolidation of political values. Therefore, experiences and circumstances during emerging adulthood have a lifelong impact.

9

Consider attitudes about same-sex marriage. A few decades ago, many homosexual people were “in the closet.” As a result, young heterosexual adults were totally unaware that any gay or lesbian person might want to be married, and the political leadership was decidedly homophobic.

The political climate has changed dramatically in recent years, as of February 2014, 17 U.S. states allow same-sex marriages. The present generation is more approving than the generation of a decade ago. Those who were young adults 60 years ago mostly disapprove (only 31 percent favor same-sex marriage) compared to young adults now (70 percent are in favor). As you can see from Figure 1.4, recent trends affect every cohort, but emerging adults are much more likely to be influenced by current trends than any older cohort, even the one immediately preceding them.

Sometimes demographic characteristics rather than current events reflect the historical context. For example, the baby boomers, those born between 1946 and 1964, are experiencing quite a different late adulthood than did earlier cohorts because there are so many of them. Their numbers have already led to an increase in the age at which a person qualifies for Social Security benefits in the United States; similar changes have been made to social programs in many other nations.

By contrast, the current cohort of young adults is relatively small, and their birth rate is low. That means they will have fewer children and grandchildren when they are older—perhaps a blessing, perhaps not, but certainly this trend represents a cohort change.

10

The Socioeconomic Context

socioeconomic status (SES) A person’s position in society as determined by income, wealth, occupation, education, and place of residence. (Sometimes called social class.)

Another pervasive context is socioeconomic status, abbreviated SES. Sometimes SES is called social class (as in middle class or working class). SES reflects income and much more, including occupation, education, and neighborhood.

Consider U.S. families that are composed of an infant, an unemployed mother, and a father who earns $18,000 a year. Their SES would be low if the wage earner were an illiterate dishwasher living in an urban slum, but it would be much higher if the wage earner were a postdoctoral student living on campus and teaching part-time.

As this example makes clear, income alone does not define SES, especially when the historical context is considered. Moreover, even poverty is less clearly defined than some people think. The traditional poverty level in the United States is set only by food costs and family size, although food basics have become much cheaper and housing more expensive. The traditional standards have not changed, so a family of three is below the 2013 poverty threshold if their household income is under $19,530. A revision of the poverty definition is under way and takes into account housing, medical care, and various subsidies (Short, 2011).

11

Developmentalists note that policies and practices regarding poverty vary from nation to nation, which affects the economic context and thus the developmental path for people in each nation. For example, in the United States the gap between rich and poor has increased in the past two decades. This has led to a larger disparity in life expectancy between the rich and the poor: Richer people are living longer than they did, but poorer people are dying at about the same age as they did 20 years ago.

The socioeconomic context is also affected by the national and historical contexts, including the proportion of the population in each cohort, as Visualizing Development (p. 12) explains.

The size of the disparity in income and education within a nation varies substantially around the world, and many conditions—health, family size, and housing among them—are affected as a result. Thus, the socioeconomic context is more critical in some jurisdictions than in others, as when health care is provided to everyone equally, or is paid privately. Examples appear in almost every later chapter. Suffice it to emphasize now that cohort, nation, and SES always affect each person’s development.

Development Is Multicultural

culture A system of shared beliefs, norms, behaviors, and expectations that persist over time and prescribe social behavior and assumptions.

In order to learn about “all kinds of people, everywhere, at every age,” it is necessary to study people of many cultures. For social scientists, culture is “the system of shared beliefs, conventions, norms, behaviors, expectations and symbolic representations that persist over time and prescribe social rules of conduct” (Bornstein et al., 2011, p. 30).

social construction An idea that is based on shared perceptions, not on objective reality. Many age-related terms, such as childhood, adolescence, yuppie, and senior citizen, are social constructions.

Thus, culture is far more than food or clothes; it is a set of ideas, beliefs, and patterns. Culture is a powerful social construction, that is, a concept created, or constructed, by a society. Social constructions affect how people think and act—what they value, ignore, and punish.

12

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Socioeconomic Status and Human Development

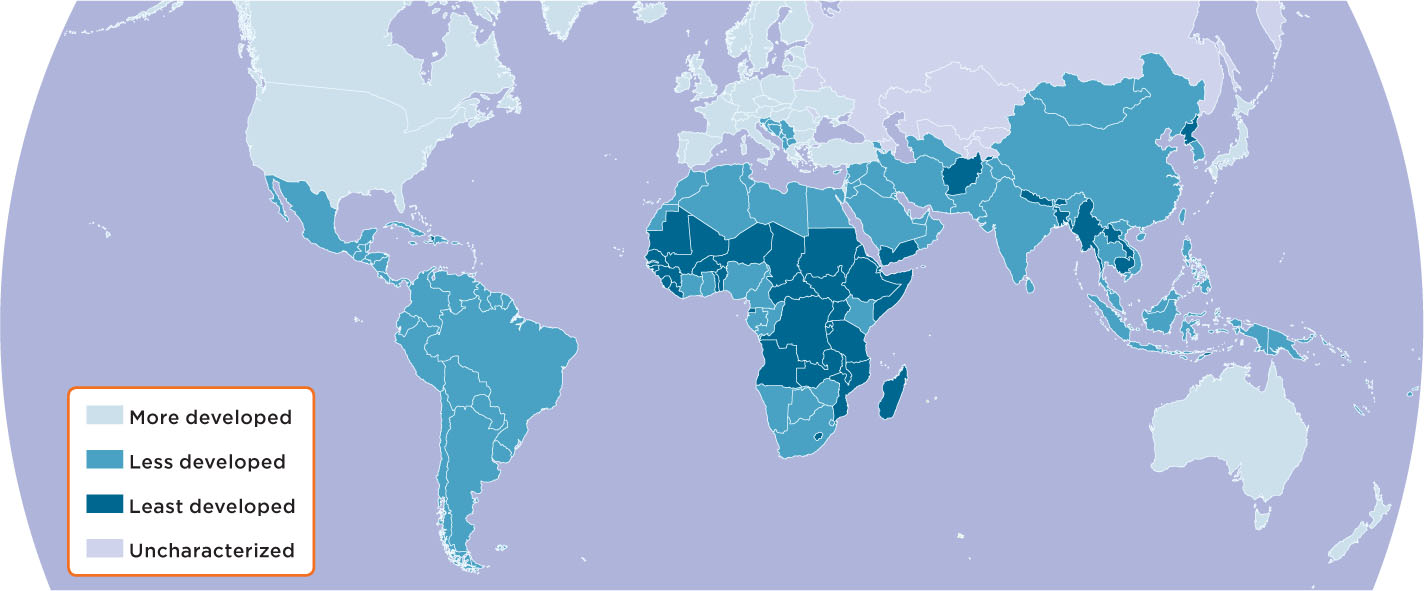

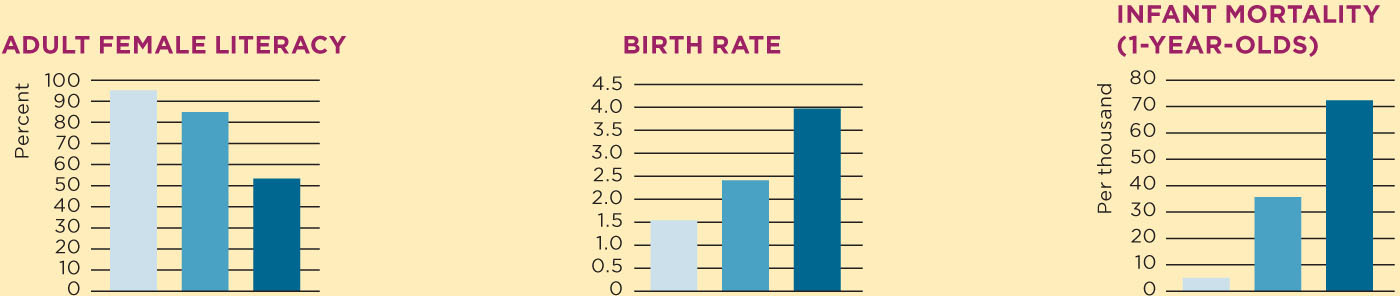

Globally and locally, socioeconomic status is one of the most accurate predictors of health. Poverty rates and level of education almost always correlate with health indicators (such as mortality) in just about every phase of the life span. Less developed countries typically have higher birth rates, but they also have much higher rates of mortality in the first year of life. Simply, and sadly, that means that more babies are born, and more die, in impoverished nations.

GLOBAL TRENDS

The United Nations categorizes nations as more, less, or least developed, based on economic growth. As indicated here, a nation’s economic status correlates closely with birth rate, which itself correlates with levels of female literacy.

This is a rough guide. For example, fewer newborns die in their first year in the United States than in nations with high poverty rates, but the U.S. infant mortality rate is higher than 33 other nations, some (such as Portugal and Greece) with lower average income.

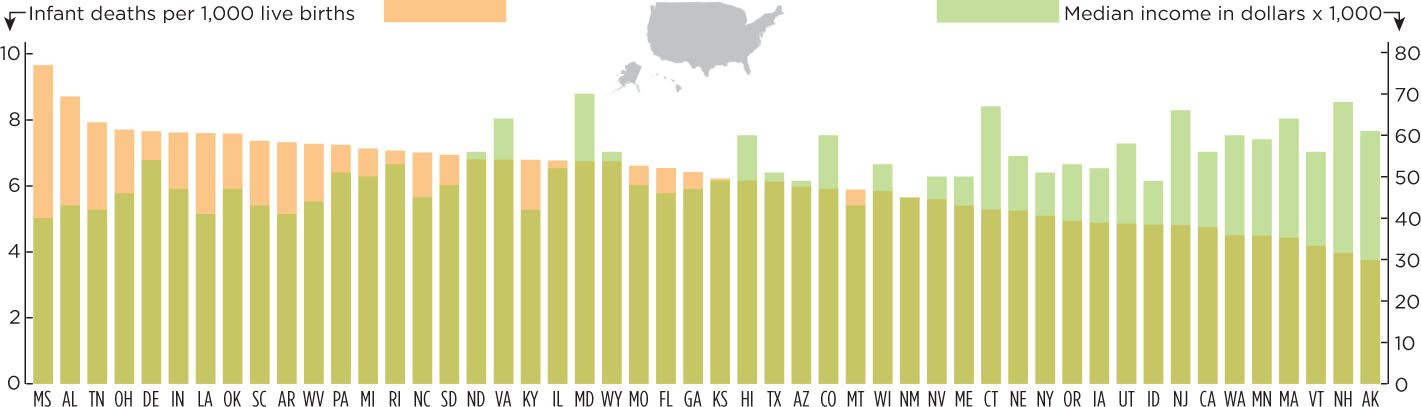

INFANT MORTALITY IN THE UNITED STATES

About two-thirds of infant deaths in the United States occur within the first 28 days of life. The single biggest cause of infant death in the United States is preterm birth.

Source: U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, CURRENT POPULATION SURVEY, 2011, 2012, AND 2013 ANNUAL SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC SUPPLEMENTS.

13

Each family, community, and college has a particular culture, and for any one person these cultures may clash. For example, decades ago my friend from a small rural town arrived for her first college class wearing her Sunday best: a matching striped skirt, jacket, and blouse. She looked at her classmates, realized a culture clash, and went directly to a used-clothing store to buy jeans and a T-shirt. On the next day she looked like the other students, but she still was shocked by their assumptions about authority, sex, religion, and much else.

Although it is important to take a multicultural perspective, be careful. Sometime people overgeneralize, as when they speak of Asian culture or Hispanic culture. That way of generalizing invites stereotyping, as if there were no cultural differences between people from Korea and Japan, for instance, or those from Mexico and Guatemala. An additional complication is that individuals within every culture sometimes rebel against their culture’s expected “beliefs, conventions, norms, behaviors.”

Thus the words culture and multicultural need to be used carefully, especially when they are applied to individuals, including oneself. Cultural pride may foster happiness, but as now explained, it may harm both the person and the community (Morrison et al., 2011; Reeskens & Wright, 2011).

Deficit or Just Difference?

Humans tend to believe that they, their nation, and their culture are better than others. This way of thinking has benefits: Generally, people who like themselves are happier, prouder, and more willing to help strangers. However, that belief becomes destructive if it reduces respect and appreciation for people from another group. [Lifespan Link: The major discussion of ethnic identity is in Chapter 19.]

difference-equals-deficit error The mistaken belief that a deviation from some norm is necessarily inferior to behavior or characteristics that meet the standard.

Developmentalists recognize the difference-equals-deficit error, which is the assumption that people unlike us (different) are inferior (deficit). Sadly, when humans realize that their way of thinking and acting is not universal, they tend to believe that those who think or act differently are to be pitied, feared, or encouraged to change.

The difference-equals-deficit error is one reason a careful multicultural approach is necessary. Being stuck in only one cultural perspective is too narrow, but it is just as narrow to assume that another culture is wrong and inferior—or the opposite, right and superior. Assumptions are dangerous, especially when they arise from culture.

A multicultural perspective allows us to see how different cultures view the same phenomenon—either as an asset or as a deficit (Marschark & Spencer, 2003). For example, cultures that discourage dissent also foster social harmony. Is harmony worth the harm of punishing rebels? The opposite is also true—cultures that encourage dissent also value independence. Whether you personally are inclined to appreciate or protest particular values, assuming that dissent is valuable or destructive, remember that the opposite reaction has merit.

The difference-equals-deficit understanding of language development goes further: In some cultures, children who talk too much are considered disrespectful. Consider the experience of one of my students:

My mom was outside on the porch talking to my aunt. I decided to go outside; I guess I was being nosey. While they were talking I jumped into their conversation which was very rude. When I realized what I did it was too late. My mother slapped me in my face so hard that it took a couple of seconds to feel my face again.

[C., personal communication]

Notice how much this student continues to reflect the norms of her culture, as she labels her own behavior “nosey” and “very rude.” She later wrote that she expects children to be seen but not heard, and that her son makes her “very angry” when he interrupts. Might the children whose North American parents encouraged them to be talkative become misfits if they live in some other cultures?

14

Learning Within a Culture

Russian developmentalist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) was a leader in describing how cultures vary in the education they provide (Wertsch & Tulviste, 2005). He noticed that adults from the varied cultures of the Soviet Union (Asians and Europeans, representing many religions) taught their children whatever beliefs and habits they might need as adults, but specifics differed markedly. [Lifespan Link: A major discussion of sociocultural theory appears in Chapter 2, page 52, and a discussion of Vygotsky appears in Chapter 9.]

Vygotsky believed that guided participation is a universal process used by mentors to teach cultural knowledge, skills, and habits. Guided participation can occur through school instruction, but more often it happens informally, through “mutual involvement in several widespread cultural practices with great importance for learning: narratives, routines, and play” (Rogoff, 2003, p. 285). Each culture guides toward different goals.

Inspired by Vygotsky, Barbara Rogoff studied cultural transmission in Guatemalan, Mexican, Chinese, and U.S. families. Adults always guide children, but clashes occur if parents and teachers are of different cultures. In one such misunderstanding, a teacher praised a student to his mother:

Teacher: Your son is talking well in class. He is speaking up a lot.

Mother: I am sorry.

[Rogoff, 2003, p. 311; from Crago, 1992, p. 496]

Of course, this does not mean that either talking or listening to children is harmful: quite the opposite. However, do not assume that any particular cultural practice is best; difference in not always deficit.

Ethnic and Racial Groups

ethnic group People whose ancestors were born in the same region and who often share a language, culture, and religion.

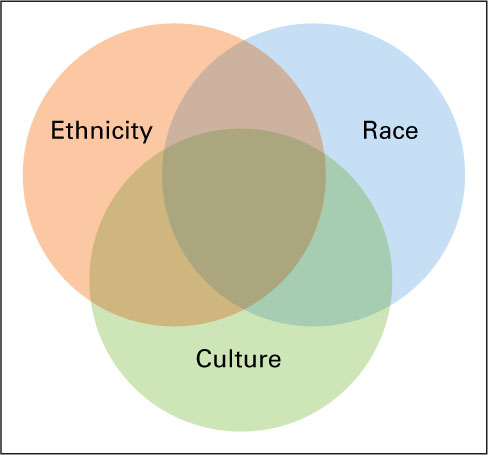

The terms culture, ethnicity, and race are confusing, as they often overlap (see Figure 1.5). Members of an ethnic group almost always share ancestral heritage and often have the same national origin, religion, and language (Whitfield & McClearn, 2005). Consequently, ethnic groups often share a culture, but not necessarily. People may share ethnicity but differ culturally (e.g., people of Irish descent in Ireland, Australia, and North America), and people of one culture may come from several ethnic groups (consider British culture).

Ethnicity is a social construction, a product of the social context, not biology. It is nurture, not nature. For example, African-born people who live in North America typically consider themselves African, but African-born people living in Africa identify with a more specific ethnic group. Many Americans are puzzled by civil wars (e.g., in Syria, or Sri Lanka, or Kenya) because people of the same ethnicity seem to be bitter enemies, but those opposing sides see many ethnic differences between them.

15

Ethnic identity flourishes when co-ethnics are nearby and outsiders emphasize differences. This is particularly obvious when racial identity is connected to ethnicity. Race is a social construction—and a misleading one. There are good reasons to abandon the term and good reasons to keep it, as the following explains.

{{span data-type='termref' data-term='fn_1_op' tabindex='0'}}OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES*{{/span}}

Using the Word {{em}}Race{{/em}}

race A group of people who are regarded by themselves or by others as distinct from other groups on the basis of physical appearance, typically skin color. Social scientists think race is a misleading concept, as biological differences are not signified by outward appearance.

The term race categorizes people on the basis of physical differences, particularly outward appearance. Historically, most North Americans believed that race was an inborn biological characteristic. Races were categorized by color: white, black, red, and yellow (Coon, 1962).

It is obvious now, but was not a few decades ago, that no one’s skin is really white (like this page) or black (like these letters) or red or yellow. Social scientists are convinced that race is a social construction and that color terms exaggerate minor differences.

Genetic analysis confirms that the concept of “race” is based on a falsehood. Although most genes are identical in every human, those genetic differences that distinguish one person from another are poorly indexed by appearance (Race, Ethnicity, and Genetics Working Group of the American Society of Human Genetics, 2005). Skin color is particularly misleading because dark-skinned people with African ancestors have “high levels of genetic population diversity” (Tishkoff et al., 2009, p. 1035) and because dark-skinned people whose ancestors were not African share neither culture nor ethnicity with Africans.

Race is more than a flawed concept; it is a destructive one. It is used to justify racism, which over the years has been expressed in myriad laws and customs, with slavery, lynching, and segregation directly connected to the idea that race was real. Racism continues today in less obvious ways (some of which are highlighted later in this book), undercutting the goal of our science of human development—to help all of us fulfill our potential.

Since race is a social construction that leads to racism, some social scientists believe that the term should be abandoned. Cultural differences influence development, but racial differences do not. A study of census categories used by 141 nations found that only 15 percent use the word race on their census forms (Morning, 2008). Only in the United States does the census still separate race and ethnicity, stating, for example, that Hispanics “may be of any race.”

Cognitively, labels encourage stereotyping (Kelly et al., 2010). As one scholar explains:

The United States’ unique conceptual distinction between race and ethnicity may unwittingly support the longstanding belief that race reflects biological difference and ethnicity stems from cultural difference. In this scheme, ethnicity is socially produced but race is an immutable fact of nature. Consequently, walling off race from ethnicity on the census may reinforce essentialist interpretations of race and preclude understanding of the ways in which racial categories are also socially constructed. [Morning, 2008, p. 255]

Observation Quiz Do you see any differences between these two people that might be cultural?

Answer to Observation Quiz: One man wears a cap, the other doesn’t; one laughs with wide-open mouth, only one has a moustache. Such difference could be cultural, or could be only personal preference.

16

All of this suggests that, to avoid racism, we should abandon the word race.

But there is an opposite perspective, and it is a powerful one (Bliss, 2012). In a nation with a history of racial discrimination, reversing that history may require recognizing race, allowing those who have been harmed to be proud of their identity. The fact that race is a social construction, not a biological distinction, does not make it meaningless. Particularly in adolescence, people who are proud of their racial identity are likely to achieve academically, resist drug addiction, and feel better about themselves (Crosnoe & Johnson, 2010).

Furthermore, documenting ongoing racism requires data to show that many medical, educational, and economic conditions—from low birthweight to college graduation, from family income to health insurance—reflect racial disparities. To overcome such disparities, race must first be recognized.

Consider the results of one scientific study. An anonymous survey of 4,915 employees at several corporations found that when most workers endorsed color-blind sentiments, such as “Employees should downplay their racial and ethnic differences,” Black employees were less proud and less engaged in their work. By contrast, when workers believed that “policies should support ethnic and racial diversity,” Black employees were more committed to their jobs. According to the authors of this study, the entire organization suffered when color blindness was the norm (Plaut et al., 2009).

Similar conclusions have been reached by many social scientists, who find that to be color-blind is to be subtly racist (e.g., sociologists Marvasti & McKinney, 2011; anthropologist McCabe, 2011). Two political scientists studying the criminal justice system found that people who claim to be color-blind display “an extraordinary level of naivete” (Peffley & Hurwitz, 2010, p. 113).

As you see, strong arguments support both sides of this issue. In this book, we refer to ethnicity more often than to race, but we speak of race or color when the original data are reported that way. Appendix A shows changes in the proportions of people of various races in the United States. Would pride or depression increase if data were reported only by national origin? Racial categories may crumble someday, but not yet.

Development Is Multidisciplinary

Scientists usually specialize, studying one phenomenon in one species at one age. Such specialization provides a deeper understanding of the rhythms of vocalization among 3-month-old infants, for instance, or of the effects of alcohol on adolescent mice, or of widows’ relationships with their grown children. (The results of these studies inform later sections of this book.)

However, human development requires insights and information from many scientists, past and present, in many disciplines. Our understanding of every topic benefits from multidisciplinary research; scientists hesitate to apply general conclusions about human life until they are substantiated by several disciplines, each with specialization.

Genetics and Epigenetics

The need for multidisciplinary research is obvious when considering genetic analysis. When the Human Genome was first mapped, some thought that humans became whatever their genes destined them to be—heroes, killers, or ordinary people. However, multidisciplinary research quickly showed otherwise. Yes, genes affect every aspect of behavior. But even identical twins, with identical genes, differ biologically, psychologically, and socially (Poulsen et al., 2007). The reasons are many, including how they are positioned in the womb and non-DNA influences in utero, both of which affect birthweight and birth order, and dozens of other epigenetic influences throughout life (Carey, 2012). [Lifespan Link: Mapping of the human genome is discussed in Chapter 3, page 78.]

epigenetic Referring to the effects of environmental forces on the expression of an individual’s, or a species’, genetic inheritance.

We now know that all important human characteristics are epigenetic. The prefix epi- means “with,” “around,” “above,” “after,” “beyond,” or “near.” The word epigenetic, therefore, refers to the factors that surround the genes, affecting genetic expression.

17

“Epi” influences begin soon after conception, as biochemical elements silence certain genes, in a process called methylation. Methylation changes over the life span, affecting genetic expression (Kendler et al., 2011). Some epigenetic influences (e.g., injury, temperature extremes, drug abuse, and crowding) impede development, while others (e.g., nourishing food, loving care, and active play) facilitate it. Research far beyond the discipline of genetics, or even the broader discipline of biology, is needed to discover all the epigenetic effects. [Lifespan Link: The major discussion of epigenetics is in Chapter 3, page 77.]

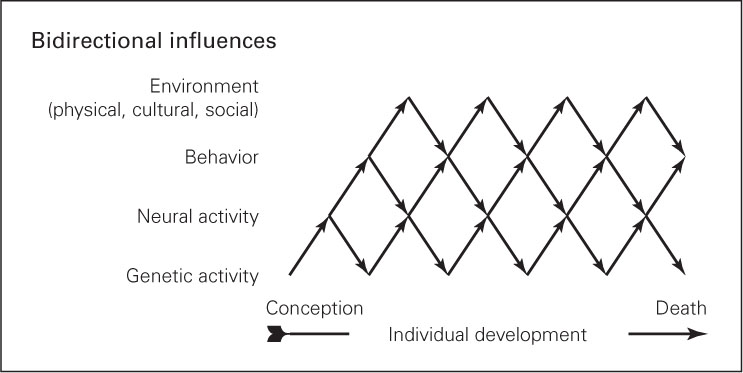

The inevitable epigenetic interaction between genes and the environment (nature and nurture) is illustrated in Figure 1.6. That simple diagram, with arrows going up and down over time, has been redrawn and reprinted many times to emphasize that genes interact with environmental conditions again and again in each person’s life (G. Gottlieb, 2010).

Multidisciplinary Research on Depression

Consider severe depression, the cause of 65 million lost years of productive life every year worldwide (P. Y. Collins et al., 2011). Depression is partly genetic and neurological—certain inherited brain chemicals make people sad and uninterested in life. This condition is caused not only by neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin but also by growth factors such as GDNF (glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor), the product of one gene that makes neurons grow or stagnate (Uchida et al., 2011).

Depression is also developmental: It increases and decreases at certain ages (Kapornai & Vetró, 2008; Kendler et al., 2011). For instance, the incidence of clinical depression suddenly rises in early adolescence, particularly among girls (Maughan et al., 2013).

Child-rearing practices have an impact as well. Depressed mothers smile and talk to their infants less than other mothers; in turn, the infants become less active and verbal. A researcher who studies mother–infant interaction told nondepressed mothers to do the following with their 3-month-olds for only three minutes:

to speak in a monotone, to keep their faces flat and expressionless, to slouch back in their chair, to minimize touch, and to imagine that they felt tired and blue. The infants…reacted strongly,…cycling among states of wariness, disengagement, and distress with brief bids to their mother to resume her normal affective state. Importantly, the infants continued to be distressed and disengaged…after the mothers resumed normal interactive behavior.

[Tronick, 2007, p. 306]

Thus, even three minutes of mock-depressive behavior makes infants act depressed. If a mother is actually depressed, her baby will be, too.

When all the research is considered, whether a particular person is depressed depends on dozens of factors, each of which is the focus of a particular academic discipline. To mitigate depression, then, and to prevent those 65 million productive years from being lost to humanity each year, dozens of factors must be understood.

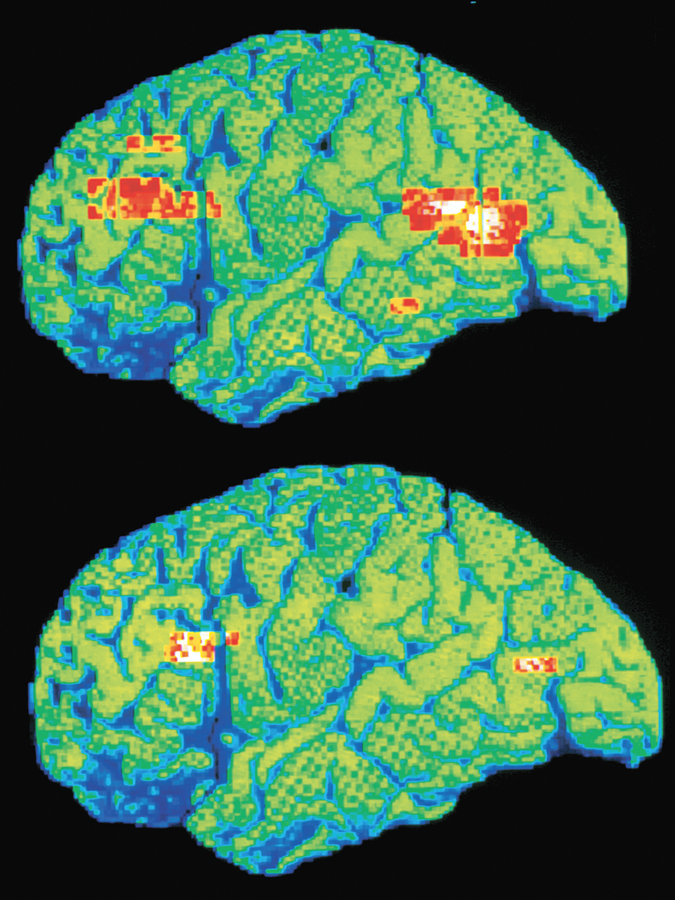

For adults as well as children, many genetic, biochemical, and neurological factors distinguish depressed individuals from other adults (Kanner, 2012; Poldrack et al., 2008), yet moods and behaviors are also powerfully affected by experience and cognition (Huberty, 2012; van Praag et al., 2012). Again, nature is affected by nurture. A person with depressing relationships and experiences is likely to develop the brain patterns characteristic of depression, and vice versa.

18

Scientists have found the following dozen factors linked to depression.

- Low serotonin in the brain, as a result of an allele of the gene for serotonin transport (neuroscience)

- Caregiver depression in childhood, especially postpartum depression with exclusive mother-care (psychopathology)

- Low exposure to daylight, as in winter in higher latitudes, causing low mood called SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder) (biology)

- Malnutrition, particularly low hemoglobin (nutrition)

- Lack of close friends, especially when entering a new culture, school, or neighborhood (anthropology)

- Diseases, including Parkinson’s and AIDS, and drugs to treat diseases (medicine)

- Disruptive social interaction, such as breakup with a romantic partner (sociology)

- Death of mother before age 10 (psychology)

- Absence of father during childhood—especially because of divorce, less so because of death or migration (family studies)

- Siblings with eating disorders (genetics)

- Poverty, especially in nations with large disparity between rich and poor (economics)

- Low cognitive skills, including illiteracy and lack of exposure to stimulating ideas (education)

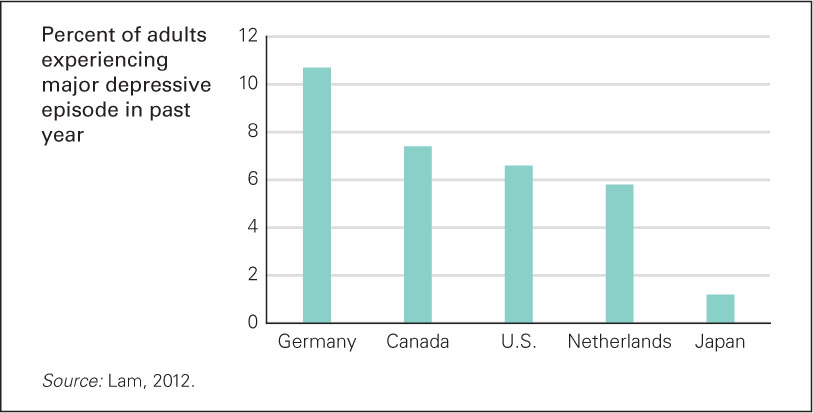

As you see, discovery of each of these factors arises from research in a different discipline (italicized above in parentheses). This list is only partial; dozens more factors have been suggested as causing depression, with all scholars recognizing that some people are affected by some factors more than others. Remember that scientists learn from each other, which means that disciplines overlap. Lack of close confidants, for instance, is noted not only by anthropologists, but also by sociologists and psychologists. Furthermore, culture, climate, and politics all have an effect on depression, although the particulars are debatable. For example, consider the national differences shown in Figure 1.7. At least six explanations have been offered for the disparity between one nation and another—some genetic, some cultural, and some a combination of the two.

A multidisciplinary approach is crucial in alleviating every impairment, not only depression: Currently in the United States, a combination of cognitive therapy, family therapy, and antidepressant medication is often more effective than any one of these three alone. International research finds that depression is quite high in some populations in some places (e.g., half the women in Pakistan) and low in others (e.g., about 3 percent of the nonsmoking men in Denmark), again for a combination of reasons (Flensborg-Madsen et al., 2011; Husain et al., 2011; von dem Knesebeck et al., 2011).

No single factor determines any outcome, and no single discipline portrays the entire story of human life. Indeed, some people who experience one, and only one, of the dozen factors listed above are not depressed at all.

19

Multidisciplinary research leads to better treatment. For instance, postpartum depression is linked to birth experiences, particularly drugs that medical researchers discovered to make birth easier for the mother. Without psychological research, they might never have realized that their practices could harm later development. Family studies have shown that fathers can become active, affectionate, and lively caregivers, protecting infants from maternal depression. This finding has helped psychologists, who now include fathers when treating mothers who are depressed.

Multidisciplinary research broadens and deepens the perspective of every scientist. Almost every circumstance that affects human development entails risks and benefits, which are often best understood by another discipline. That leads to the next topic, plasticity.

Development Is Plastic

The term plasticity denotes two complementary aspects of development: Human traits can be molded (as plastic can be), and yet people maintain a certain durability of identity (as plastic does). The concept of plasticity in development provides both hope and realism—hope because change is possible, and realism because development builds on what has come before.

Dynamic Systems

dynamic systems A view of human development as an ongoing, ever-changing interaction between the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial influences. The crucial understanding is that development is never static but is always affected by, and affects, many systems of development.

Plasticity is basic to our contemporary understanding of human development. This is evident in one of the newest approaches, called dynamic systems. The idea is that human development is an ongoing, ever-changing interaction between the body and mind and between the individual and every aspect of the environment, including all the systems described in the ecological approach. The dynamic-systems approach began in disciplines that focus on changes in the natural world.

[S]easons change in ordered measure, clouds assemble and disperse, trees grow to a certain shape and size, snowflakes form and melt, minute plants and animals pass through elaborate life cycles that are invisible to us, and social groups come together and disband.

[Thelen & Smith, 2006, p. 271]

Note the word dynamic: Physical contexts, emotional influences, the passage of time, each person, and every aspect of the ecosystem are always interacting, always in flux, always in motion. For instance, a new approach to developing the motor skills of children with autism spectrum disorder stresses the dynamic systems that undergird movement—the changing aspects of the physical and social contexts (Lee & Porretta, 2013). [Lifespan Link: The major discussion of autism spectrum disorder is in Chapter 11.]

The dynamic-systems approach builds on the multidirectional, multicontextual, multicultural, and multidisciplinary nature of development. With any developmental topic, stage, or problem, the dynamic-systems approach urges consideration of all the interrelated aspects, every social and cultural factor, over days and years. Plasticity and the need for a dynamic-systems approach are most evident when considering the actual lived experience of each individual. My nephew David is one example.

20

A CASE TO STUDY

{{span data-type='termref' data-term='fn_1_cs' tabindex='0'}}David*{{/span}}

My sister-in-law contracted rubella (also called German measles) early in her third pregnancy; it was not diagnosed until David was born, blind and dying. Immediate heart surgery saved his life, but surgery to remove a cataract destroyed one eye.

The doctor then decided the cataract on the other eye should not be removed until the virus was finally gone. But one dead eye and one thick cataract meant that David’s visual system was severely impaired for the first five years of his life. That affected all his other systems. For instance, he interacted with other children by pulling their hair. Fortunately, the virus occurred prenatally after the critical period for hearing had been reached. Because the systems of the body are interrelated, David developed extraordinary listening ability.

But the virus did harm his thumbs, ankles, teeth, feet, spine, and brain. He was admitted to special preschools—for the blind, for children with cerebral palsy, for children who were intellectually disabled. At age 6, when some sight was restored, he entered regular public school, learning academics but not social skills—partly because he was excluded from physical education.

By age 10 he had blossomed intellectually: David had skipped a year of school and was a fifth-grader, reading at the eleventh-grade level. Before age 20 he learned a second and a third language. In young adulthood, he enrolled in college.

As development unfolded, the interplay of systems was evident. His family context allowed him to become a productive adult, and happy. He told me, “I try to stay in a positive mood.”

Remember, plasticity cannot erase a person’s genes, childhood, or permanent damage. The brain destruction and compensation from that critical period of prenatal development remain. David is now 47; he still lives with his parents. Yet his listening skills are impressive. He told me

I am generally quite happy, but secretly a little happier lately, especially since November, because I have been consistently getting a pretty good vibrato when I am singing, not only by myself but also in congregational hymns in church. [He explained vibrato:] When a note bounces up and down within a quartertone either way of concert pitch, optimally between 5.5 and 8.2 times per second.

David works as a translator of German texts, which he enjoys because, as he says, “I like providing a service to scholars, giving them access to something they would otherwise not have.” As his aunt, I have seen him repeatedly overcome disabilities. Plasticity is dramatically evident. This case illustrates all five aspects of the life-span perspective (see Table 1.3).

|

Characteristic Multidirectional. Change occurs in every direction, not always in a straight line. Gains and losses, predictable growth, and unexpected transformations are evident. |

Application in David’s Story David’s development seemed static (or even regressive, as when early surgery destroyed one eye), but then it accelerated each time he entered a new school or college. |

| Multidisciplinary. Numerous academic fields—especially psychology, biology, education, and sociology, but also neuroscience, economics, religion, anthropology, history, medicine, genetics, and many more—contribute insights. | Two disciplines were particularly critical: medicine (David would have died without advances in surgery on newborns) and education (special educators guided him and his parents many times). |

| Multicontextual. Human lives are embedded in many contexts, including historical conditions, economic constraints, and family patterns. | The high SES of David’s family made it possible for him to receive daily medical and educational care. His two older brothers protected him. |

| Multicultural. Many cultures—not just between nations but also within them—affect how people develop. | Appalachia, where David and his family lived, has a particular culture, including acceptance of people with disabilities and willingness to help families in need. Those aspects of that culture benefited David and his family. |

| Plasticity. Every individual, and every trait within each individual, can be altered at any point in the life span. Change is ongoing, although it is neither random nor easy. | David’s measured IQ changed from about 40 (severely intellectually disabled) to about 130 (far above average), and his physical disabilities became less crippling as he matured. Nonetheless, because of a virus contracted before he was born, his entire life will never be what it might have been. |

Differential Sensitivity

Plasticity emphasizes that people can and do change, that predictions are not always accurate. More accurate predictions could improve prevention of developmental problems.

Three insights gained by developmentalists have advanced the benefits of prediction. Two of them you already know: (1) Nature and nurture always interact, and (2) certain periods of life are particularly sensitive for particular developments.

21

Both of these insights were apparent in David’s case. His inborn characteristics affected his ability to learn, but, unlike the case for babies born a century ago with rubella, nurture from family and professionals limited the impact of many handicaps. As for critical and sensitive periods, David’s attendance in preschool may be one reason he fared so well later on, because developmentalists now know that education from birth to age 4 has profound influence on later learning.

differential sensitivity The idea that some people are more vulnerable than others to certain experiences, usually because of genetic differences.

The third factor to aid prediction and target intervention is a recent discovery, differential sensitivity. The idea is that because of their genes some people are more vulnerable than others to particular experiences. This vulnerability can work in both directions: The same genes affect people for better or for worse, depending on postconception experiences.

Can you remember something you heard in childhood that still affects you, perhaps a criticism that stung or a compliment that inspired? Now think of what that same comment meant to the person who uttered it or might have meant to another child. Those words stayed with you, but they might have been forgotten by others. That is differential sensitivity.

More generally, many scientists have found genes, or circumstances, that work both ways—they predispose people to being either unusually successful or severely pathological (Belsky et al., 2012; Kéri, 2009). This idea is captured in the folk saying “Genius is close to madness”: The same circumstance (genius) can become a gift for an entire society, or a burden for an individual, or have no effect at all.

22

Differential sensitivity is apparent at every point in the life span, from prenatal development throughout old age. An experiment involved stressing pregnant rhesus monkeys and then observing how responsive those monkeys were to their newborns. The mothers who were inclined to be nurturing were even more nurturing than usual; the mothers who were already less warm were even less nurturing than usual. Stress affected those mothers in opposite ways, and then that affected their offspring, again with differential sensitivity.

To control for the influence of genes, the monkeys in utero when the mothers were stressed were compared to other monkeys born to the same mothers with unstressed pregnancies. It was apparent that the stressed nurturing mothers had babies who were superior to their siblings, and the stressed cold mothers had babies who were inferior. Thus stress affected them all, for better or worse, in differential sensitivity (Shirtcliff et al., 2013).

SUMMING UP

Development is multidirectional, with gains and losses evident at every stage. An ecological-systems perspective emphasizes the many contexts that affect each person, including the immediate family, nearby institutions, and the overall cultural values of the society. Cohort and socioeconomic status always affect each life.

Cultural influences are pervasive, albeit sometimes unrecognized. Social constructions, including ethnicity and race, are tangled with cultural values, making culture not only crucial but also complex. To untangle the influences on development, many academic disciplines provide insight on how people grow and change over time. The interaction of all the developmental contexts cannot be fully grasped by any one discipline.

Each person’s development is plastic, with the basic substance of each individual life moldable by contexts and events. Genes can make a person more or less vulnerable to certain experiences, for better or for worse.