21.3 Selective Gains and Losses

Aging neurons, cultural pressures, historical conditions, and past education all affect adult cognition. None of these can be controlled directly by an individual adult. Nonetheless, many researchers believe that adults make crucial choices about their intellectual development.

For example, why have number skills declined more for recent cohorts than for earlier ones? The reason may not be past math curricula (as was suggested) but rather modern adults’ reliance on calculators instead of paper-

Similarly, memory would improve if we did not use directories and speed dial to phone or text our friends. But do the cultural artifacts of modern life make us lazy intellectually? Or have people merely focused on new challenges?

Accumulating Stressors

Many health decisions that adults make prioritize immediate comfort over long-

stressor Any situation, event, experience, or other stimulus that causes a person to feel stressed. Many circumstances that seem to be stresses become stressors for some people but not for others.

Now we focus on another factor that slows down cognition: stress. Every life is stressful. Some stresses become stressors. A stressor is an experience, circumstance, or condition that affects a person. Thus a stress is external; if stresses are internalized, they become stressors.

Between ages 25 and 65, family members die, disasters destroy homes, jobs disappear, and even welcome events—

If organ reserves are depleted, the physiological toll of stress can lower immunity, increase blood pressure, speed up the heart, reduce sleep, and produce many other reactions that can lead to cognitive loss as allostatic load increases. Similar to organ reserve, there is a cognitive reserve: Although the mind benefits from ongoing use, when people must suddenly perform difficult cognitive tasks they are less able to think clearly. They may make impulsive decisions, and those decisions may be destructive.

STRINGER/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

616

Humans have always experienced stresses, some of which becomes stressors, and they have developed ways to cope with them, sometimes with biological homeostasis and allostasis, sometimes more directly with cognitive strategies. As you will see, the choice as to which coping method to use may lead to intellectual strength or impairment.

Coping Methods

Especially for Doctors and Nurses A patient complains of a headache or stomachache, but laboratory tests and CAT scans find no physical cause. What could it be?

Response for Doctors and Nurses: Stressors increase allostatic load, so the headache or stomachache could be caused by stress. Be careful, however, because both you and the patient may be engaged in avoidant coping. The patient may deny the stress and blame you for suggesting it, and you yourself may be avoiding responsibility. Emotional and contextual problems impact physical health, so medical experts cannot dismiss them.

Stressors increase all the bad habits described in Chapter 20—

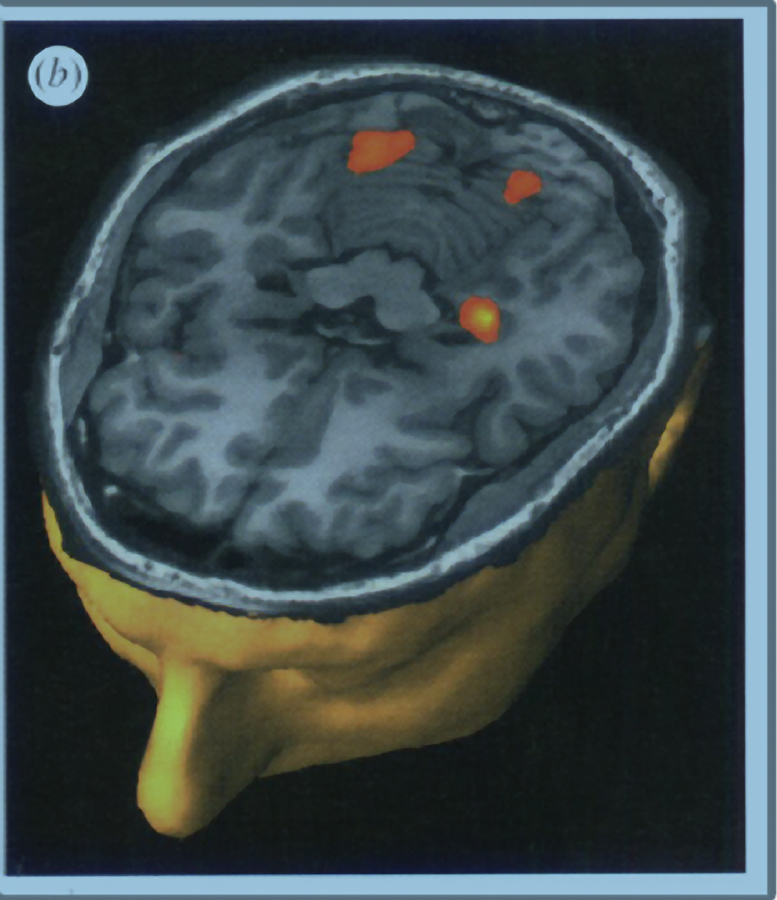

Similarly, stress hormones not only undercut thinking in the moment, but can also reduce mental ability for the future. Stress affects more than logic; chronic stress increases depression and other psychological illnesses that impair thinking, and it attacks the brain itself (Marin et al., 2011; McEwen & Gianaros, 2011).

Reactions to stress can cause yet more stress, which means that stressors accumulate. For example, a longitudinal study of married couples in their 30s found that if the husband’s health deteriorated, the chance of divorce increased. Thus one reaction to the stress of illness was to do something that increased stress. This effect was apparent with all couples, particularly for well-

The rate of divorce also increases when parents have children with special needs (Price, 2010). Conversely, for some couples having a child with serious problems brings partners closer together (Solomon, 2012). Apparently having a child with special needs is always stressful, and thus creates a stressor. But how people then cope with that stressor is crucial to their mental health.

avoidant coping A method of responding to a stressor by ignoring, forgetting, or hiding it.

Coping involves cognition because people choose what to do. Abuse of alcohol and other drugs is one form of avoidant coping. Ignoring a problem, either literally forgetting it or hiding it (one person who owed back taxes threw all official letters under his bed, unopened), is the worst way of coping—

problem-

emotion-

Psychologists distinguish two positive ways of coping with stress. In problem-

Biologically and culturally, the two sexes may respond differently to stress. Men tend to be problem-

Women, however, are more emotion-

617

This gender difference in coping explains why a woman might get upset if a man doesn’t want to talk about his problems and why a man might get upset if a woman just wants to talk instead of taking action. Both problem-

Choosing Methods

Not only do people need to figure out the best strategy to deal with each particular problem, but they also need to figure out when other people will help and when they will not (Aldwin, 2007). Getting social support is generally a good strategy—

The best coping strategy depends on the situation. Worse than either problem-

weathering The gradual accumulation of stressors over a long period of time, wearing down a person’s resilience and resistance.

The stress that a person endures in childhood and adolescence may become evident in morbidity during the adult years. A U.S. study of 65,000 adults compared many signs of poor health, such as hypertension and insulin resistance. The gradual accumulation of such biochemical stressors is called weathering, and this study found that weathering happened faster among African Americans—

The average life span of African American adults is about 4 years shorter than that of European Americans until about age 80, when some data find a “cross over,” with African Americans living longer. Curiously, Latinos live longer than either group (National Center for Health Statistics, 2013). Social support?

Weathering has a direct impact on intelligence. In studies conducted in the United States in the 1980s, the average IQ score of African Americans was 15 points lower than the average score for European Americans (Neisser et al., 1996). Earlier researchers hypothesized that these differences were genetic. However, later research suggests that stress may be the cause. Specifically:

- The Black–

White IQ gap narrowed, from about 15 points to about 10 between 1972 and 2002 (Dickens & Flynn, 2006) and continues to shrink— more in some abilities than others. - The racial differences are apparent in vocabulary but not in learning abilit (Fagan & Holland, 2007).

- The racial differences are less dramatic at age 4 and most dramatic at about age 25.

All three of these findings suggest that stress may reduce the IQ of African Americans. Note that the IQ gap is most evident in early adulthood.

Ideally, with age and experience adults learn to respond wisely. Over the years of adulthood, a more positive attitude toward life develops, which makes it easier to reinterpret stresses so that they do not fester (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). Often,

[o]lder individuals have had the opportunity to learn how to cope with stressful experiences and how to adjust their expectations…. On the basis of age and experience, older persons have developed more effective skills with which to manage stressful life events and to reduce emotional stress.

[Penninx & Deeg, 2000]

618

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Stress in Adulthood

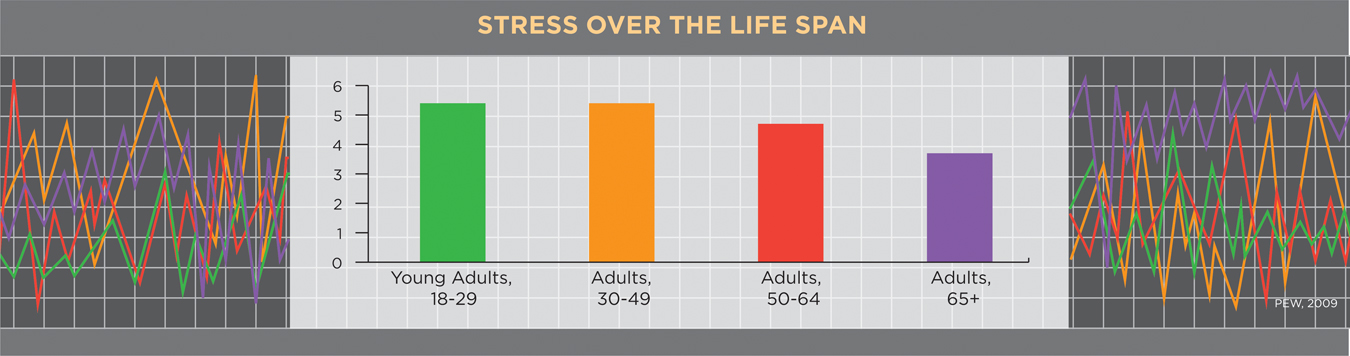

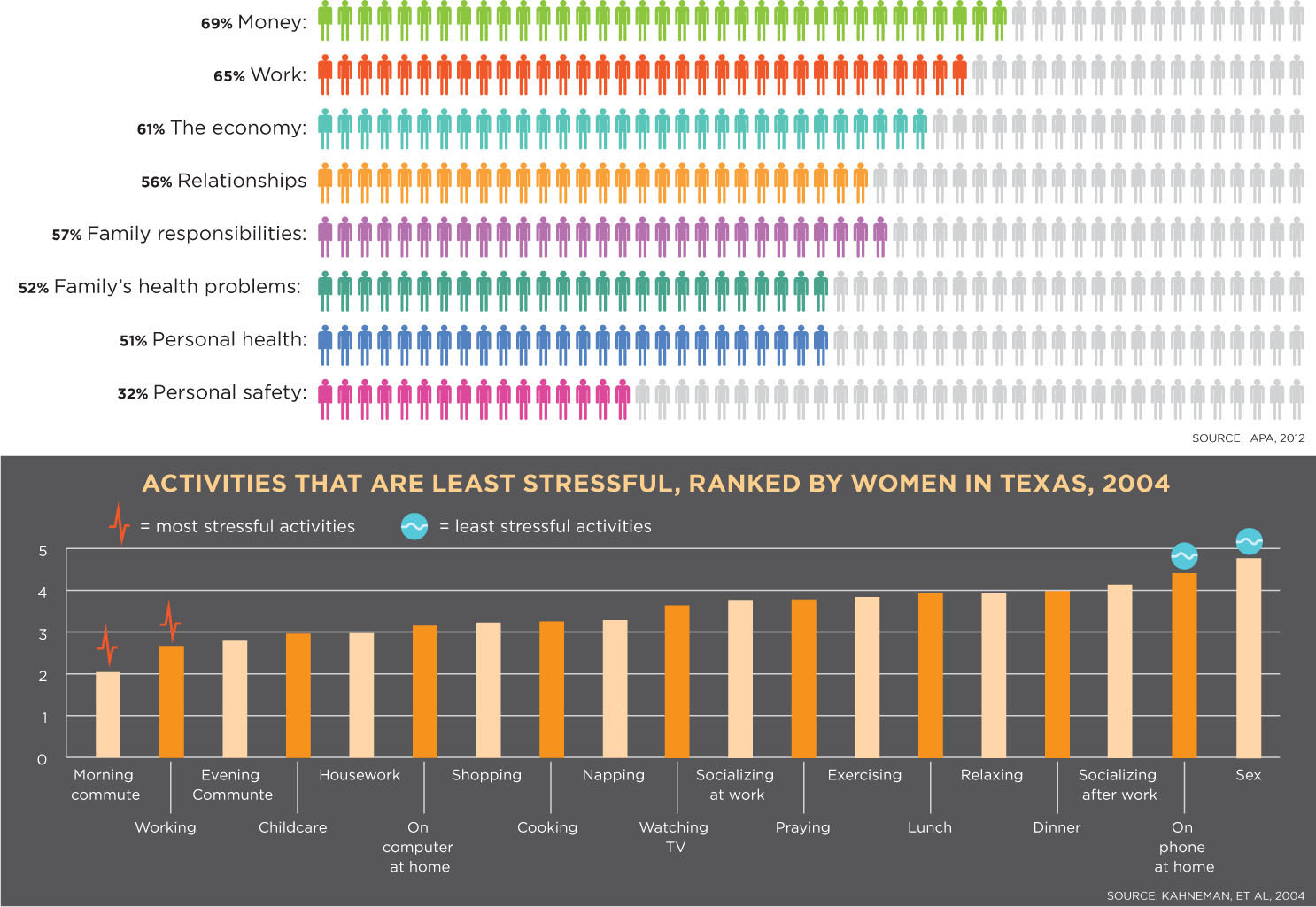

Stresses and coping strategies differ from generation to generation. Developmentalists believe that emerging adults today may have more stresses than in the past because education is increasingly important and unemployment is higher. However, adults without jobs or supportive families may be more stressed than emerging adults since they feel more responsible for their problems. Fortunately, the ability to cope may improve with age.

Just as there are many ways to cope with stress, there are many ways to measure it. One common one is to simply ask people what stresses them and another way is experience sampling-

WHAT CAUSES STRESS IN DAILY LIFE

Depending on exactly how the question is phrased, adults identify different triggers for their daily stress. For many, it is work, family, health, and safety concerns that worry them.

619

For people of every background, age brings another advantage. Emerging adulthood is “a time of heightened hassles.” Once life settles down, some stresses (dating, job hunting, moving) occur less frequently. Adults “are more adept at arranging their lives to minimize the occurrence of stressors” (Aldwin, 2007, p. 298). (Visualizing Development, p. 618, compares stress in different age groups.)

Remember that attitude sometimes determines whether or not an event becomes a stressor, and whether that stressor decreases over time. For instance, post-

religious coping The process of turning to faith as a method of coping with stress.

Some people respond to their stressors with religious coping, believing that there is some divine purpose for the problem. Social scientists find that religious coping is particularly likely when people have unexpected illnesses or disasters. As with other forms of coping, sometimes religious coping mitigates a stressor, other times it makes it worse (Burke et al., 2013; Thuné-Boyle et al., 2013). During adulthood, religious faith and practice tend to increase; past experience coping with stress may be the reason.

Of course, natural disasters, such as earthquakes, and personal tragedies, such as the death of a loved one, are always stressful at the time. The surprise is that they are usually overcome, with many adults ignoring some disruption and reinterpreting events. Instead of dwelling on their misfortune, they emphasize their good fortune—

When challenges are successfully met, not only do people feel more effective and powerful, but the body’s damaging responses to stressors—

A CASE TO STUDY

Coping with Katrina

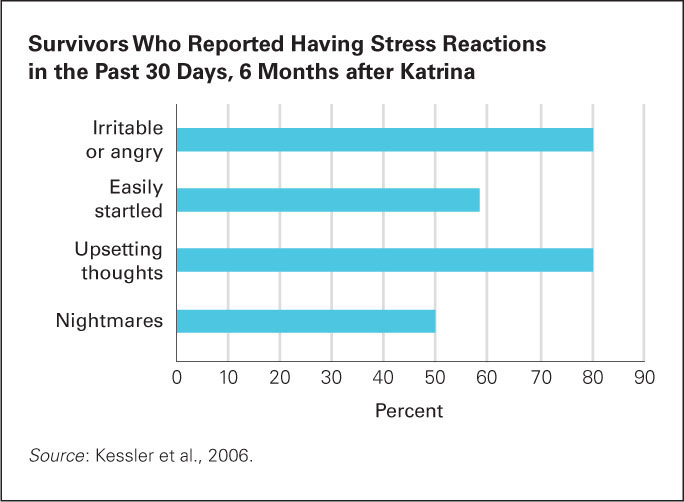

Developmentalists are following the hundreds of thousands of people in Louisiana and Mississippi who were uprooted by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Many of them lost homes and jobs, went without food and water, and knew people who died. Not surprisingly, their stressors increased. For instance, one study of survivors from New Orleans six months after the flood found that most of them had stress reactions: Almost all were irritable and had upsetting thoughts, and half had nightmares (see Figure 21.2.).

The accumulation of stressors led to many physical and psychological difficulties. One in nine suffered serious mental health problems, twice as many as before the hurricane. Another 20 percent had mild to moderate mental illness, again double the earlier rate (Kessler et al., 2006). Given the trauma of the storm (a major stress) and the inept official response (which led to ongoing hassles), this is not surprising.

However, longitudinal studies found that the same stressors also led to increased resilience, with three out of four people reporting that they found a deeper sense of purpose after Katrina. Only one person in 250 had made a plan for suicide, which was one-

620

A college student who traveled to Mississippi to help survivors provides a firsthand account. She was expecting to see people defeated by their losses. In her words:

Three hundred college students from Ohio traveled to Mississippi to help survivors of Katrina. Arriving six months after the devastation, they saw rusted cars, shells of homes, and even clothing still stuck to tree branches. But they also met hundreds of people putting their lives together, including teachers at a head start program, who eagerly got back to work within a few weeks after the storm. One student was awed by the “resilient optimism rising above the rubble.” She quoted a local volunteer who said “You make a living with what you earn; you make a life with what you give.”

[Feerasta, 2006]

Although the actual hurricane occurred years ago, those who experienced it continue to cope with the aftermath. Social scientists continue to study them. One team considered religious beliefs before and after Katrina. Those caught in Katrina who believed that God is vengeful and punishing were more likely to suffer, but those who believed that God is caring and benevolent coped well, experiencing post-

Humans seem to have a recovery reserve that is activated under stress, similar to the organ reserve explained in Chapter 17. According to a related set of studies, it seems that extra effort and alertness are summoned when emergencies arise, even if those affected are overtired and in a noisy environment. This reserve works well for the moments of the emergency, especially if people feel there is something they can do. No wonder the teachers in New Orleans after Katrina wanted to get back to work.

This may explain a familiar reaction to final exams: Some students study intensely, perform well … and then collapse, maybe even getting sick after their last exam. More research is needed, but it seems possible that adults gradually develop better coping methods to adapt to the vicissitudes of life (Masten & Wright, 2010; Aldwin & Gilmer, 2013).

Optimization with Compensation

selective optimization with compensation The theory, developed by Paul and Margaret Baltes, that people try to maintain a balance in their lives by looking for the best way to compensate for physical and cognitive losses and to become more proficient in activities they can already do well.

Paul and Margret Baltes (1990) developed a theory called selective optimization with compensation to describe the “general process of systematic function” (P. B. Baltes, 2003, p. 25) by which people maintain a balance in their lives as they grow older. They believe that people seek to optimize their development, selecting the best way to compensate for physical and cognitive losses, becoming more proficient at activities they want to perform well.

Selective optimization with compensation applies to every aspect of life, ranging from choosing friends to playing baseball. Each adult seeks to maximize gains and minimize losses, practicing some abilities and ignoring others. Choices are critical, because any ability can be enhanced or diminished, depending on how, when, and why a person uses it. It is possible to “teach an old dog new tricks,” but learning requires that adults want to learn those new tricks.

When adults are motivated to do well, few age-

As Baltes and Baltes (1990) explain, selective optimization means that each adult selects certain aspects of intelligence to optimize and neglects the rest. If the ignored aspects happen to be the ones measured on intelligence tests, then IQ scores will fall, even if the adult’s selection improves (optimizes) other aspects of intellect. The brain is plastic over the entire life span, developing new dendrites and activation sequences, adjusting to whatever the person chooses to learn (Smith & Baltes, 2013; Karmiloff-

621

For example, suppose someone who is highly motivated to learn about a particular area of the world (perhaps the Rocky Mountains) notices that aging affects his or her vision, making it hard to read fine print. That person might get reading glasses, increase computer type size (compensation), and read closely every article about the Rockies, ignoring news articles about everything else (selectivity). If an IQ vocabulary item happened to be avalanche, the person might score correctly, but he or she would fail most questions of general knowledge. In that way, knowledge increases (optimization) in depth but decreases in breadth.

Multitasking

One example of selective optimization is multitasking, which becomes more difficult with every passing decade (Reuter-

This fact is obvious when people drive a car while talking on a cell phone. Such behavior is particularly dangerous for older drivers because as the brain focuses on the conversation, the neurological shift needed to react to a darting pedestrian is slower (Asbridge et al., 2013). Some jurisdictions require drivers to use hands-

Some say that passenger conversation is as distracting as cell phone talk, but that is not true: Years of practice have taught adult passengers (though not young children) when to stop talking so that the driver can focus on the road (S. G. Charlton, 2009). If passengers do not quiet down on their own, experienced drivers stop listening and replying because they know they must concentrate.

This is why statements such as “I can’t do everything at once” and “Don’t rush me” are more often said by older adults than teenagers. Adults compensate for slower thinking by selecting one task at a time. Resources within the brain are increasingly limited with age, but compensation allows optimal functioning (Freund, 2008).

One father tried to explain this concept to his son as follows:

I told my son: triage

Is the main art of aging.

At midlife, everything

Sings of it. In law

Or healing, learning or play,

Buying or selling—

In remembering—

Cut losses, let profits ring.

Specifics rise and fall

By selection.

[Hamill, 1991]

Expert Cognition

expertise Specialized skills and knowledge developed around a particular activity or area of specific interest.

Another way to describe gains and losses is to say that everyone develops expertise, becoming a selective expert, specializing in activities that are personally meaningful, anything from car repair to gourmet cooking, from illness diagnosis to fly fishing. As people develop expertise in some areas, they pay less attention to others. For example, each adult usually elects to watch just some channels on television and ignoring vast realms of experience. Each adult has no interest in attending certain events for which others wait in line for hours.

ADEK BERRY/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

622

Culture and context guide us in selecting areas of expertise. Many adults born 60 years ago are much better than more recent cohorts at writing letters with distinctive and legible handwriting. In childhood they practiced penmanship, became expert in it, and maintained that expertise. Today’s schools and, consequently, children make other choices: Reading, for instance, is now crucial for every child, unlike a century ago when adult illiteracy was common.

Experts, as cognitive scientists define them, are not necessarily people with rare and outstanding proficiency. Although sometimes the term expert connotes an extraordinary genius, to researchers it means more—

An expert is not simply someone who knows more or who is talented in a particular way. That is only the beginning. At a certain point, accumulated knowledge, practice, and experience become transformative, putting the expert in a different league from others. The quality as well as the quantity of cognition is advanced. Expert thought is (1) intuitive, (2) automatic, (3) strategic, and (4) flexible, as we now describe.

Intuitive

Novices follow formal procedures and rules. Experts rely more on past experiences and immediate contexts; their actions are therefore more intuitive and less stereotypic than those of the novice. The role of experience and intuition is evident, for example, during surgery. Outsiders might think medicine is straightforward, but experts understand the reality:

Hospitals are filled with varieties of knives and poisons. Every time a medication is prescribed, there is potential for an unintended side effect. In surgery, collateral damage is inherent. External tissue must be cut to allow internal access so that a diseased organ may be removed, or some other manipulation may be performed to return the patient to better health.

[Dominguez, 2001, p. 287]

In one study, many surgeons saw the same videotape of a gallbladder operation and were asked to talk about it. The experienced surgeons anticipated and described problems twice as often as did the residents (who had also removed gallbladders, just not as many) (Dominguez, 2001). Data on physicians indicate that the single most important question to ask a surgeon is, “How often have you performed this operation?” The novice, even with the best, most recent training, is less skilled than the expert.

This is true in psychotherapy as well, according to a study that compared novices and experts—

Another example of expert intuition is chicken-

Poultry owners once had to wait five to six weeks before the appearance of adult feathers enabled them to separate cockerels (males) from pullets (hens). Egg producers wanted to buy and feed only pullets, so they were intrigued to hear that some Japanese had developed an uncanny ability to sex day-

[Myers, p. 55]

623

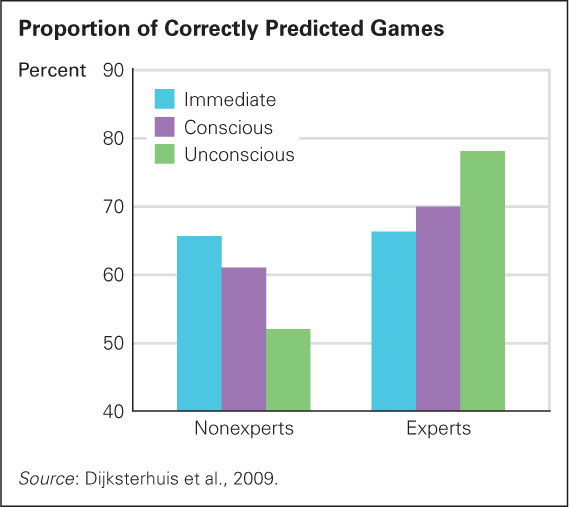

One experiment that studied the relationship between expertise and intuition involved 486 college students who were asked to predict the winners of soccer games not yet played. The students who were avid fans (the experts) made better predictions when they had a few minutes of unconscious thought instead of when they had the same number of minutes to mull over their choice (see Figure 21.3). Those who didn’t care much about soccer (the nonexperts) did worse overall, but they did especially poorly when they had time to use unconscious intuition (Dijksterhuis et al., 2009).

The details of this experiment are intriguing. For 20 seconds, all participants were shown a computer screen with four soon-

Nonexperts did no better than chance. They did worse after thinking about their answer, especially when the thought was unconscious. Perhaps the stress of doing math interfered with their thinking. By contrast, the predictions of the experts were not much better than those of the nonexperts when they guessed immediately, a little better when they had two minutes to think, and best of all after unconscious thought. Apparently, the experts’ knowledge of soccer helped them most when they were consciously thinking of something else.

Automatic

This experiment with soccer experts and nonexperts also confirms that many elements of expert performance are automatic; that is, the complex action and thought required by most people have become routine for experts, making it appear that most aspects of the task are performed instinctively. Experts process incoming information quickly, analyze it efficiently, and then act in well-

For example, adults are much better at tying their shoelaces than children are (adults can do it in the dark), but they are much worse at describing how they do it (McLeod et al., 2005). When experts think, they engage in “automatic weighting” of various unverbalized factors. This automatic thinking can be disrupted by the words that nonexperts use, which distort rather than clarify the thinking process (Dijksterhuis et al., 2009, p. 1382).

This is apparent if you are an experienced driver and try to teach someone else to drive. Excellent drivers who are inexperienced instructors find it hard to recognize or verbalize things that have become automatic—

This may explain why, despite powerful motivation, quicker reactions, and better vision, teenagers have three times the rate of fatal car accidents as adults do (Insurance Institute, 2012). Sometimes teenage drivers deliberately take risks (speeding, running a red light, drinking, and so on), but they more often simply misjudge and misperceive conditions that a more experienced driver would automatically notice.

624

The same gap between knowledge and instruction occurs when a computer expert tries to teach a novice what to do, as I know myself when my daughters try to help me with the finer points of Excel. They are unable to verbalize what they know, although they can do it very well with the computer. It is much easier to click the mouse or do the keystroke oneself than to teach what has become automatic.

automatic processing Thinking that occurs without deliberate, conscious thought. Experts process most tasks automatically, saving conscious thought for unfamiliar challenges.

Automatic processing is thought to explain why expert chess and Go players are much better than novices. They see a configuration of game pieces and automatically encode it as a whole, rather than analyzing it bit by bit.

A study of expert chess players (aged 17 to 81) found minor age-

When something—

Strategic

Experts have more and better strategies, especially when problems are unexpected. Indeed, strategy may be the pivotal difference between a skilled and an unskilled person. Expert chess players have general strategies for winning, and far better specific strategies for the particular responses after a move that is their specialty (Bilalic et al., 2009).

Similarly, a strategy used by expert team leaders in both the military and civilian arenas is ongoing communication, especially during slow times. Therefore, when stress builds, no team member misinterprets the previously rehearsed plans, commands, and requirements. You have witnessed the same phenomenon in expert professors: In the beginning of the semester they institute routines and policies, strategies which avoid problems later in the term.

Of course, strategies themselves need to be updated as situations change—

The superior strategies of the expert permit selective optimization with compensation. That is evident in studies of airplane pilots, a group for whom age-

In one study, trained pilots were given directions by air traffic controllers in a flight simulation (Morrow et al., 2003). Experienced pilots took more accurate and complete notes and used their own shorthand to illustrate and emphasize what they heard. For instance, they had more graphic symbols (such as arrows) than did pilots who were trained to understand air traffic instructions but who had little flight experience. Thus, even though nonexperts were trained and had the tools (note paper, pencil), they did not use them the way the experts did.

In actual flights, too, older pilots take more notes than younger ones do because they have mastered this strategy, perhaps to compensate for slower working memory. Another series of studies of pilots tested repeatedly over three years confirmed that expertise fostered better strategies, as expected (Taylor et al., 2007, 2011). But unexpected was the conclusion that experience was particularly beneficial for those whose age and genes produced slower thinking.

625

In those longitudinal studies, some deficits in memory and reaction time began to appear as the pilots aged. But expertise meant their judgment regarding piloting a plane was still good, far better than that of pilots with less experience (Taylor et al., 2007, 2011). People show age-

Flexible

Finally, perhaps because they are intuitive, automatic, and strategic, experts are also more flexible in their thinking. The expert artist, musician, or scientist is creative and curious, deliberately experimenting and enjoying the challenge when things do not go according to plan (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

Consider the expert surgeon, who takes the most complex cases and prefers unusual patients to typical ones because operating on the unusual ones might reveal sudden, unexpected complications. Compared with the novice, the expert surgeon is not only more likely to notice telltale signs (an unexpected lesion, an oddly shaped organ, a rise or drop in a vital sign) that may signal a problem but is also more flexible and willing to deviate from standard textbook procedures if those procedures seem ineffective (Patel et al., 1999).

In the same way, experts in all walks of life adapt to individual cases and exceptions—

In the field of education, best practices for the educator now emphasize flexibility and strategy, as each group of students has distinct and often erroneous assumptions. It is not helpful to simply teach the right answers; flexibility requires matching the instruction to the individual students, discovering what learning is needed (Ford & Nove, 2011).

A review of expertise finds that flexibility includes understanding which particular skills are necessary to become an expert in each profession. For example, repeated practice is needed in typing, sports, and games; collaboration skills are needed for leadership; and task management strategies are needed for aviation (Morrow et al., 2009).

Expertise and Age

The relationship between expertise and age is not straightforward. One of the essential requirements for expertise is time.

People who become experts need months—

Expertise may counteract some effects of aging (Krampe & Charness, 2006). Much depends on the task: The young have an advantage when speed is needed, but they are less adept at vocabulary. Further, they have less experience, which may be crucial for some tasks. An interesting example comes from perfumers: They need an acute sense of smell as they seek to develop new scents. Although the sense of smell typically is reduced with age, not so for perfumers. Experts outdid younger nonexperts: they had significantly developed those parts of the brain that were attuned to smell (Delon-

626

This illustrates a general conclusion from research on cognitive plasticity: Experienced adults often use selective optimization with compensation, becoming expert. This is apparent in many workplaces. The best employees may be the older, more experienced ones—

Complicated work requires more cognitive practice and expertise than routine work; as a result, such work may have intellectual benefits for the workers themselves. In the Seattle Longitudinal Study, the cognitive demands of the occupations of more than 500 workers were measured, including the complexities involved in the interactions with other people, with things, and with data. In all three occupational challenges, older workers maintained their intellectual prowess (Schaie, 2005).

One final example of the relationship between age and job effectiveness comes from an occupation familiar to all of us: driving a taxi. In major cities, taxi drivers must find the best route (factoring in traffic, construction, time of day, and many other details), all while knowing where new passengers are likely to be found and how to relate to customers, some of whom might want to talk, others not.

Research in England—

Other studies also show that people become more expert, and their brains adapt, as they practice various skills (Park & Reuter-

Family Skills

This discussion of expertise has focused on occupations—

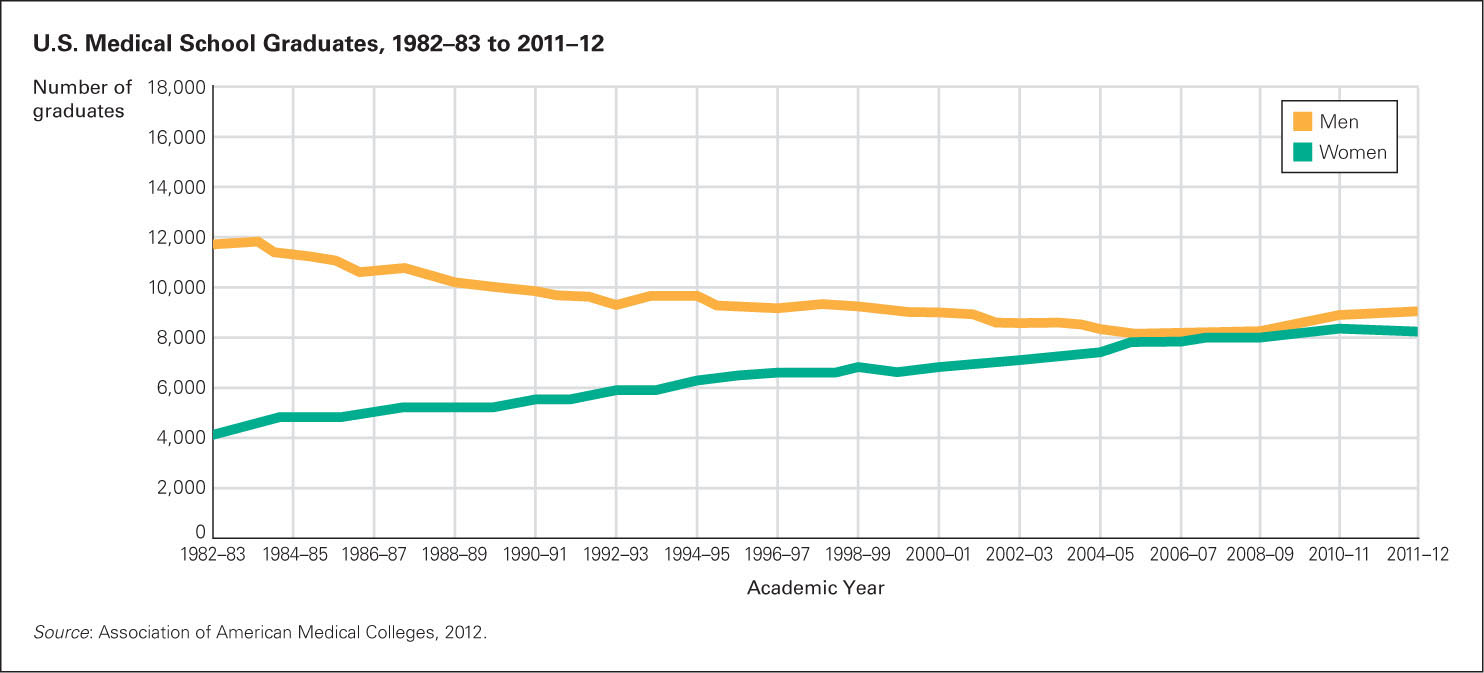

First, more women are working in occupations traditionally reserved for men. Remember from Chapter 4 that Virginia Apgar, when she earned her MD in 1933, was told she could not be a surgeon because only men were surgeons. Fortunately for the world, she became an anesthesiologist and her scale has saved millions of newborns. Today that assumption has changed; almost half the new MDs in the United States are women, and many of them have become surgeons (see Figure 21.4). More generally, most college women expect to have careers, husbands, and children, and many do so (Hoffnung & Williams, 2013).

The second major shift is that women’s work has gained new respect. In earlier generations, women sometimes said they were “just a housewife” or “a nonworking mom.” Recently, however, the importance of work at home is increasingly recognized, and men as well as women do it. We now know that not all women are good mothers or housekeepers, and that some men are expert in domestic and emotional work that was once women’s exclusive domain. Couples who switch traditional roles are no longer rare. Most believe that for children, it is best that the father have major responsibility for child rearing (Dunn et al., 2013)

627

It is no longer assumed that a “maternal instinct” is innate to every mother; many mothers experience postpartum depression, financial stress, or bursts of anger and do not provide responsive child care. Certainly in some families, fathers and grandparents provide better care for children than biological mothers do. As with other adult tasks, motivation and experience are crucial for caregiving.

The skill, flexibility, and strategies needed to raise a family are a manifestation of expertise. Here again age as well as gender is important. As noted in previous chapters, in their late teens and early 20s both sexes are at their most fertile, and young women have the fewest complications of pregnancy. But conception is only a start: In general, older parents are more patient, with lower rates of child abuse as well as more successful offspring.

This is especially true if the parents have learned from experience and can listen well, as mature parents more often do. With such parents, teenagers are more likely to avoid drug addiction and other hazards. Developmentalists have not yet identified all the components necessary to become expert in child rearing, but at least we know that such expertise exists. Some parents are far more skilled than others.

SUMMING UP

Gains and losses occur during adulthood. Every adult experiences stress and must cope with it, with some coping methods more likely to turn stress into ongoing stressors that impair health, and other strategies able to turn stresses into productive experiences.

Adults choose to become adept at some cognitive aspects and skills, charting their course by using selective optimization with compensation. As a result, they can use their cognitive resources wisely, gaining intellectual power in areas that they choose. Choices and practice over time produce expertise, which is intuitive, automatic, strategic, and flexible. Expertise allows people to continue performing well in their work and their family life throughout adulthood.

628